Man of the World by Robert Gibson

10: the banks of the swengg

No one tried to restrain him as he left the room or, a few moments later, as he left the entire building.

He had no idea what he would he have done, had he been stopped. Crazy – to have no plan… All that counted was the outcome, escape, whether by a hair’s breadth or with a mile-wide safety margin –

Instinct, with its sure knack for justification, summoned witness – the sensual witness of the afternoon sunshine rubbing his head and shoulders with soothing ointment from the sky, telling him it was right to be outside; his legs’ steadiness of pace, as he headed back into the city, endorsing his action by smoothness alone; the passport of smoothness assuring him, everything is balanced around the point called NOW. The surface of time is NOW. Depths do exist, we must admit, but only to support their surfaces (when you’re reading a face, you’re looking at the skin; you’re not X-raying the head) – Skin – surface – NOW!

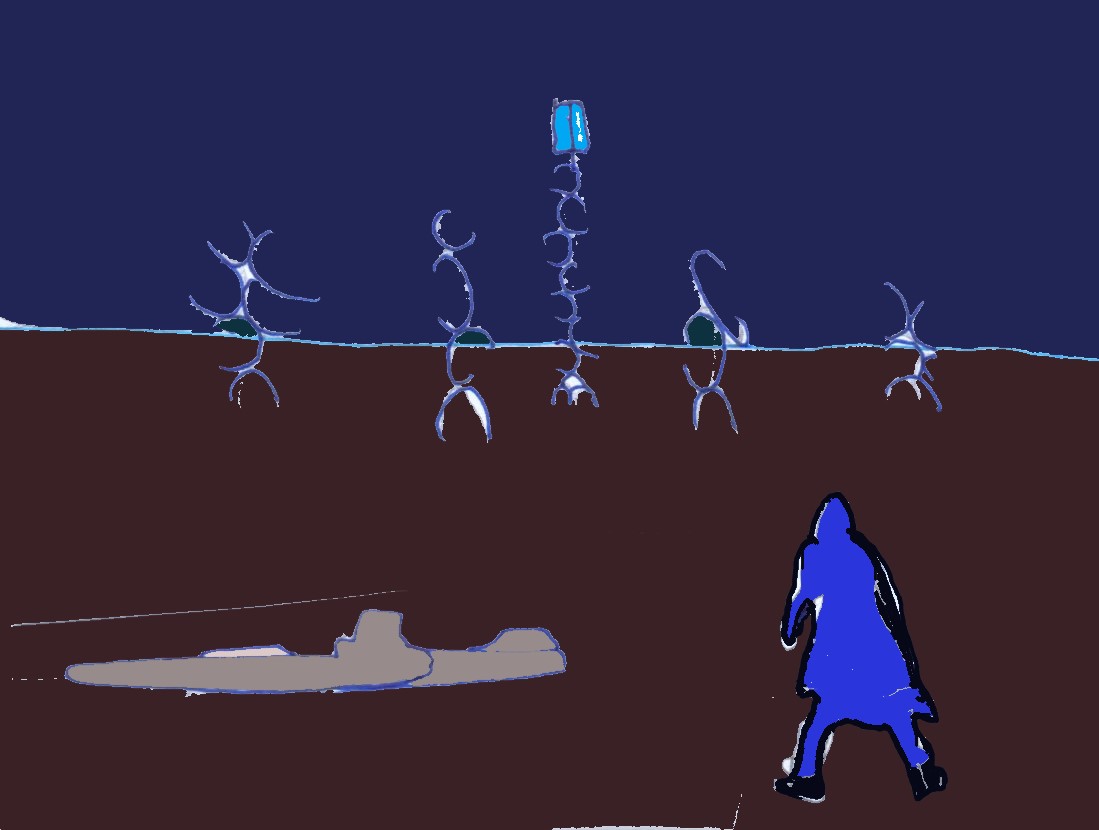

Midax thus strode, in the style of a man who knows where he is going and why; strode on without looking back. Facts might gang up to refute him later – but so what? At this moment he was travelling light.

The road became busier. Intersections and houses grew more frequent. Life buzzed around him: fellow-strollers; tranced workers walking or on skates; the rustle of tatterplants in their great iron pots; and the banal sight of doors and windows, a sight which stirred his innards with the sentimental cry, These are all homes! – moving him to picture the inhabitants’ lives, the weight of the endless history of happy NOW. Small wonder that Day 143,206,646 was really no different from Day 143,206,645. How immense was the unrecorded history of everyday happiness!

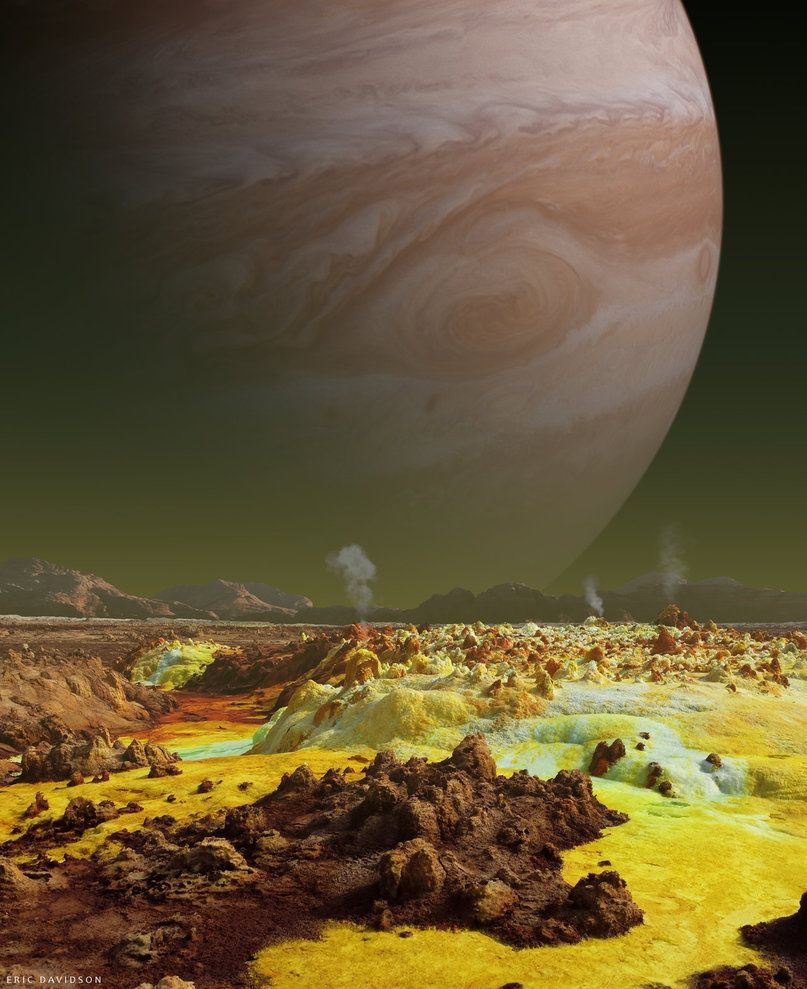

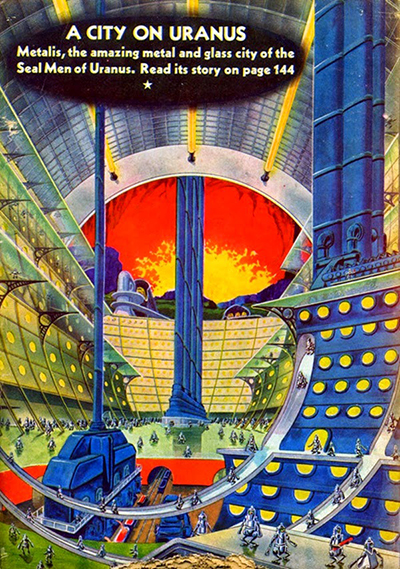

As expected, in the direction he took, the mill-breeze grew stronger. Approaching the next line of buildings he glimpsed the mast-size whirling arms of the airmill beyond. He pressed on through a cobbled alley. From there he emerged, finally, on the bank of the great canal called the Swenng.

The surface of the Swenng was pure kolv, smoother than ice, shining an extremely pale blue. Its banks were lined at hundred-yard intervals by tatterplants the size of small trees, and at four-hundred-yard intervals by the gigantic airmills which fanned the breezes which kept sail-craft plying the Swenng in both directions: a leftward current on the near side, a rightward current provided by the mills on the opposite bank. Invisible subterranean ducts, he knew, connected the mills to their source of energy, the Fount…

Midax looked to the right, in the direction of the oncoming near-side traffic, and the far-side traffic receding, down the majestic lane of canal between the parallel lines of trees. That nearest tatterplant, he knew, had 25,628 leaves. The next had exactly 17,684. The one after that, 34,291. Luxuriant data! The opulence of this ancient city’s life – a source of endless pride, of wallowing-room for the soul - was most especially reassuring to one who had just turned his back on the vista at the other end of town.

His eyes became fixed upon a hulk on the canal – a two-storey pleasure barge, sliding closer, growing massive in his sight. It was decelerating, bearing down on the spot where he stood. It bumped to a halt against the verge. The contact caused the trippers on board to stagger about, laughing. Midax’s vision darkened: his memories crowded in a nostalgic blur. He hardly saw more than the outline of the floating pile of humanity now moored in front of him. A voice hailed him from the forecastle; a voice he recognised. Around a fiddling toothpick it spoke, out of a young man’s languid face, framed with brilliant orange hair. “Midax! Hop aboard and join us…. We were just wondering when you would turn up.”

Hearty words – yet not truly from the heart. The tone and body language of Mapennel Deen, Arbiter of the Splashers, told Midax that a duel of wits had begun. Having been addressed, Midax must reply without hesitation.

Luckily the words and the strategy came to him on the instant of his need. “Prepare for a shock, Mapennel. I’m busy.”

“You look it!” brayed another Splasher, crumpling with mirth.

“Wait,” another one hooted, “he may be right – it could be quite a heavy job, trying on silver suits!”

“Get him on board, Mapennel! It’s a while since we had a fancy-dress party!”

Raucous cachinnation all over the barge.

Their leader, however, rather than give way to merriment, preferred to prolong his control.

“You mean to stand there, Midax, and tell us you’re actually staying and working with the glimmerers?”

Glimmerers. By his use of that term, Arbiter Mapennel took his stance atop a mountain of disdain, and challenged Midax to the climb.

Mapennel continued, “I know that yesterday you went to look them over for a laugh, but – ”

A girl’s voice interrupted him. “Careful, Chief – maybe he’s on to something.”

The girl – he’d seen her only once or twice before; she must be fairly new to the group – was lying at a forty-five-degree angle on the middle cabin windscreen. Her limbs were flung into a rag-doll pose of exhaustion. Her comment released another general fizz of laughter, yet Midax believed that he could detect signs of hedging, as if some were unsure and half-hearted in their mockery. News must have got around, after all, of the discovery that the onset of Sparseworld had become detectable.

No one, after hearing that news, could dismiss the topic of the great doom as irrelevant to real life.

In which case, might it actually be possible to get through to these people? Just think of that – just think how great that would be – getting the old gang to listen. Could it be done? Was it ever possible to advance through life preserving old associations alongside new, escaping the pitiless choices, the final goodbyes?

Worth trying!

“You guessed it,” he cried out to them. “There is something in it, called ‘survival’. We at the Institute are looking to see the morning after Sparseworld. Or at least, to ensure that somebody someday will see it.”

A puddle of sound, seething with murmurs and outright boos, greeted that last word, though again there was something half-hearted about the opposition. In their hesitation they looked to Mapennel for a lead.

“‘Survival’,” scoffed the Splasher chief with sincere contempt. He looked around at his followers with an air that invited them to add their scorn to his. He then glared back at Midax, saying, “I can guess how your bunch propose to ‘survive’.”

“Tell me, then. I should like to know.”

“Oho! Are you now giving out that you don’t know?”

“Having been there less than a day,” Midax coolly responded, “I admit I haven’t yet fully worked out how they plan to save the world.”

“By making do with less,” stated Mapennel, flatly. “I can tell you for sure, that’s what it’ll amount to. The bread-and-water mentality. Of the details of their plan I admit I know nothing. For all I know, it may actually work.” He began to spread out his arms. “By attenuating your lives, into a thin thin strand, you glimmerers may eke them out all the way across the chasm that lies before us, if that’s the kind of miserable fate you want. But don’t come trying to cramp us in such a fashion.”

“You talk as though it were we who threaten you,” Midax objected, “rather than the real enemy – Sparseworld.”

“I know perfectly well that you don’t threaten us. You just came to make a show, because you have found a uniform to wear.”

Amid the snickers that followed, Midax hesitated. Nothing would have been easier than to retort that the Splashers were the ones who lived for show, but to say so, at this point, would have been a bad move. Mapennel might have curled his lip at it rather promptly, might have replied that what was good enough for his idle gang was no longer admissible in a sober career man such as the high-minded Midax Rale. Therefore, Midax must deign to clear himself…. and the point was a fair one anyway: why had he come?

Why had he lurched out of the Olamic building?

In the same way that the driver of a wheeled passenger vehicle, when turning a corner, might lose control and then regain it, and cover up what had happened, making it look like some deliberate manoeuvre, – “just testing, you know – just experimenting” – so did Midax forge a pedigree of motive for his act.

“I came,” he nodded, “determined, seeing as no other way exists to catch your attention, to make a sort of necessary show. And as for the purpose of this show, it was to warn you.”

Well, not exactly. I didn’t actually know, when setting out, what I was going to do. Can I get round this? But yes! A dash of polish – a fount of assertion in the head –

“And why should we need your warning?” asked Mapennel Deen. The Splasher Chief looked surly now, bored with the duel which he was convinced he had won.

Midax replied, “I’ll tell you why, and then you can decide whether or not to be warned by me. They at the Institute seem to know so amazingly much, that they’ve started to make me look afresh at our universe. Weird sensation, I can tell you – ”

“Curly,” drawled one of the girls.

Midax hastened on, “So, what did I then start to feel? I started to feel that it – our universe – must be an early, primitive thing, still raw and pure, in which the complexity that we call life is dependent upon rare spurts, isolated outlets of the Fount. We’re so close to our Fount, we can actually see it and locate it. We’re privileged in that way. We have to be – or we wouldn’t exist. But a Fount may ebb. And when it does, when it dwindles into long-term abeyance and Sparseworld comes upon us, we can’t adapt in time.”

He had some of them interested.

“We must,” he continued, “do something special, something brilliant, lest Serenth suffer the fate of Icdon. We must achieve something on a heroic scale! Which is why I thought of you people.”

Almost, he felt he was getting away with it. Appeal to their sense of style!

But then Mapennel threw him off balance with a verbal punch of surprising coldness. No lazy drawl this time, but clipped, flat hostility:

“I have already made it clear that our group does not regard survival as the highest goal. Perhaps it is time for you to tell us how you believe your Institute will save us from the fate of Icdon. If they intend a better method than the one I have mentioned – if they can do more than make-do-with-less – then tell us. You seem to trust them. Presumably you believe you have good reason.”

In the face of this challenge, Midax judged it time to risk more candour. He did have his own suspicions, after all, gradually maturing in his mind ever since he had seen that zig-zagging aeroplane in the Luminarium.

“Here is my impression based on what I heard yesterday at the Open Day and some clues I have observed since then. The Institute, so I gather, knows how to concentrate life in some way. I believe it’s a process known technically as asset-packing; that is, by folding or pleating resources, using light as a medium. Apparently they can do it in such a way as to corrugate our stimuli – ”

“Curly!” whooped that lanky girl on the windscreen. “Yeah!” chimed another. More tinkles of merriment told Midax how he had blundered. Of course! He had blundered by using long serious words and an overlong sentence; he’d got the tone wrong and his position was beyond repair.

He lost his temper and yelled, but by this time the unanimous hurrahs of “CURLY! TURGIE!” drowned out everything else. Humiliated and disgusted, he turned his back on them all.

He went less briskly than he came. He wandered moodily back from the city centre. Out of the vale of Serenth, and back up the long slope towards the Olamic building, he plodded in a self-reproachful state, bitterly ashamed at having laid himself open to such a hurtful rebuff.

Eventually the long-dragging ache wore itself out, and, checking the logic of what he had done, he became coldly satisfied.

By the time the walk was over he was sure that he had done his duty for former friendship’s sake. He had warned them. Enough.

At the Institute’s entrance he turned and looked back over the city, his lips now curved in a smile of secret authority. He was giving orders to his imagination, and the orders were being obeyed: a drying-up operation, back along the whole trail, whereby the sad and bloody thoughts, left by his wounded pride, lost their pathetic wetness, and turned into a cool strand of recollection, which, without more ado, could be reeled in.

>>>next chapter>>>