stanley g weinbaum and the old solar system

[ + link to podcast on A Martian Odyssey ]

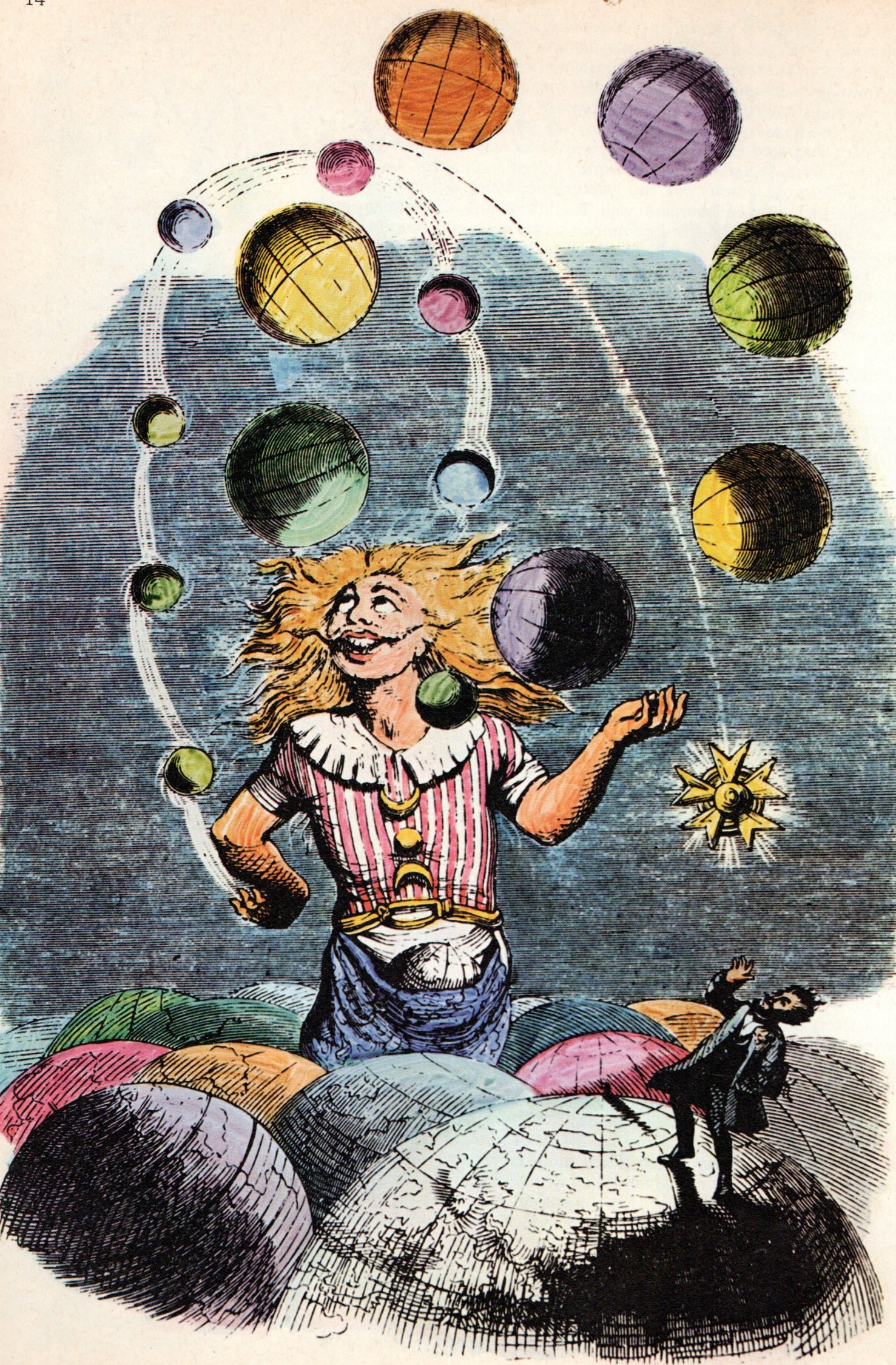

Stanley Weinbaum is famous in the history of sf as a meteoric new star for about a year and a half in the mid-1930s, during which he gave the Solar System a new coat of visionary pen-portraits.

Stid: Colourful, yet with some serious thought put into it. Picturesque, his aliens - yet they made sense in evolutionary terms, given their environment. At least, that was his aim: to make things plausible. He cared about that. And so he gave his stories an edge - a certain bite.

Zendexor: A cause-and-effect excitement.

weinbaum world by world

Venus: Parasite Planet and The Lotus Eaters.

Earth: Shifting Seas.

Mars: A Martian Odyssey (including, among its many marvels, a memorable encounter with silicon life) and its sequel Valley of Dreams.

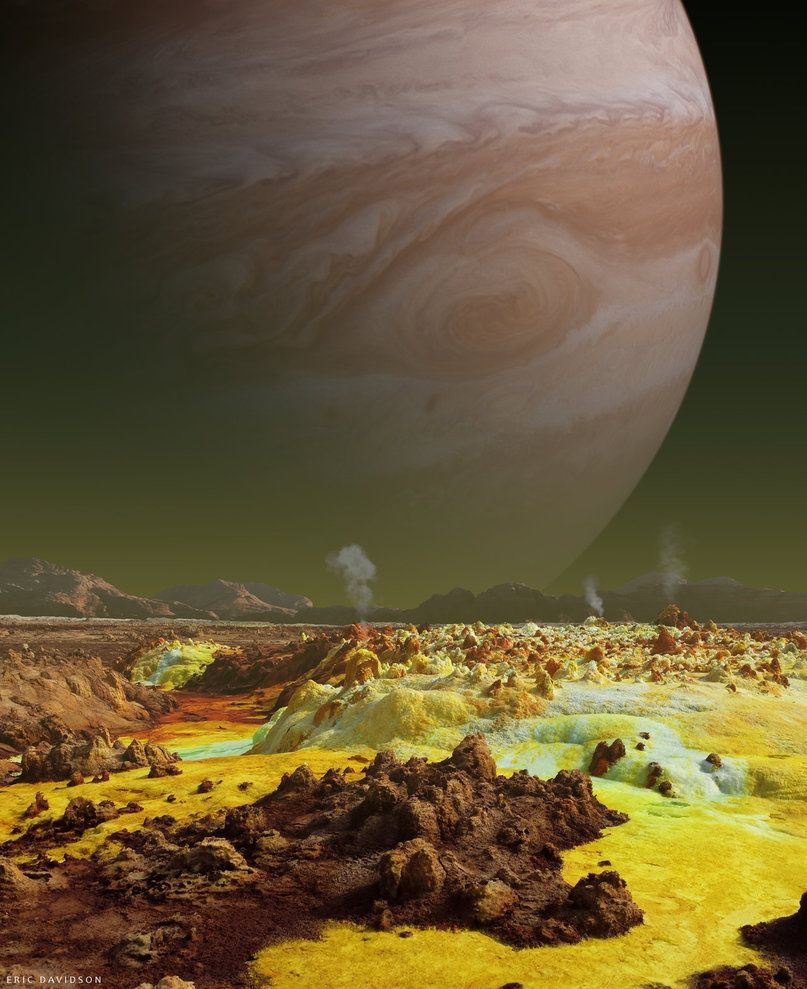

Io: The Mad Moon.

Europa: Redemption Cairn.

Ganymede: Tidal Moon (with Helen Weinbaum).

Titan: Flight on Titan.

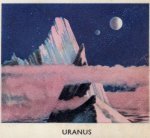

Uranus: The Planet of Doubt.

Pluto: The Red Peri.

Note: after Weinbaum's death his sister Helen Weinbaum worked up some of her late brother's notes into the story Tidal Moon, set on Ganymede. A watery Ganymede, round which an overwhelming tide flows every Ganymedean day. It is not fully consistent with the other Weinbaum stories because it mentions Io as having an atmosphere that is "mostly methane".

Harlei: To me, Tidal Moon lacks the real Weinbaum magic. Its style is rather lifeless. But all the same, it left me with a memorable idea of its version of Ganymede.

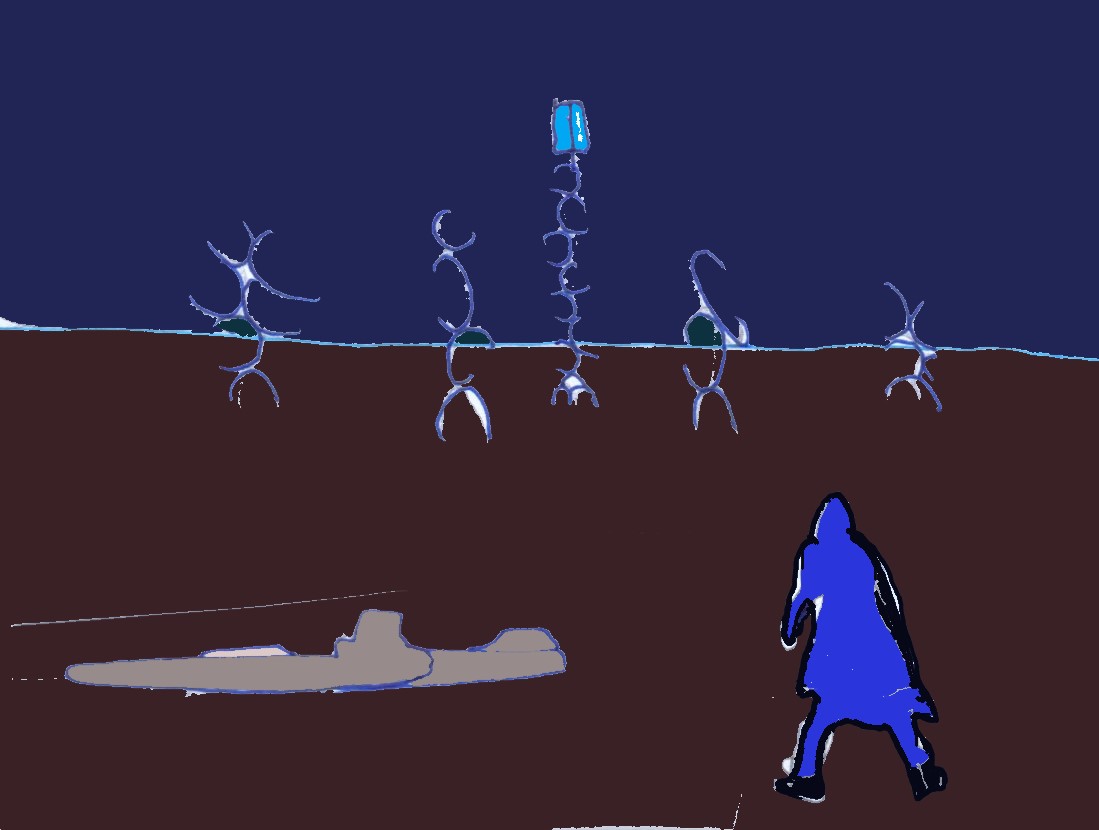

...If one excepted the scattered stilt houses in the flats, nothing broke the monotony of mountains, rocks and mudholes... He remembered the first time he had seen the square boxlike hives made of compressed cree, standing on twenty-foot poles - how he had wondered if, indeed, they could survive the flood. No one had stayed above ground long enough to find out...

As befits a Weinbaum story, there is an original biological idea: an amoeboid predator who becomes what it eats.

intelligent plants

Stid: Getting back to Stanley Weinbaum himself: I ought to add to my earlier remarks, that I don't think he always succeeded in making a good case for his aliens' distinctive features. A rare piece of negative criticism I read somewhere - I can't remember where - struck a chord in my mind -

Zendexor: Criticism of The Lotus Eaters?

Stid: That's the one! It has a memorable encounter in which biologist Patricia Hammond pleads with the intelligent vegetable (dubbed "Oscar") whom she finds on Venus:

"...But, Oscar, why - why don't you use your knowledge to protect yourselves from your enemies?"

"There is no need. There is no need to do anything. In a hundred years we shall be - " Silence.

"Safe?"

"Yes - no."

"What?" A horrible thought struck her. "Do you mean - extinct?"

"Yes."

"But - oh, Oscar! Don't you want to live? Don't your people want to survive?"

"Want," shrilled Oscar. "Want - want - want. That word means nothing."

"It means - it means desire, need."

"Desire means nothing. Need - need. No. My people do not need to survive."

Patricia after a while figures out the reason for Oscar's lack of survival instinct; she explains to her husband:

"...I think I see it now. It's this: Animals have desire and plants necessity... An animal has will, a plant hasn't. Do you see now? Oscar has all the magnificent intelligence of a god, but he hasn't the will of a worm..."

The Lotus Eaters is a remarkable story, but - I don't believe in the possibility of an intelligent plant, or at least, not one like Oscar. It seems to have developed its intelligence for no reason.

Zendexor: The point, as you observed, has been made before. Weinbaum, on this occasion, did not pay his usual attention to evolutionary factors. He failed to think up any reason why a plant should become intelligent.

Harlei: Well, I reckon that makes the impact of the story all the greater. Can't things happen without a reason? You could get intelligence developing randomly, couldn't you? The encounter with Oscar is quite eerie... makes one think of how needlessness could be a factor, a big factor, in the Universe.

Zendexor: Maybe. But while we're on the subject of plants, let's hop from Venus to Mars. For on Weinbaum's Mars, we have another angle on the vegetable kingdom. It's not separate from the animal one, there! They didn't differentiate. And thus, evolution took a very different direction.

Harlei: Tweel's nose is also a root...

intelligent planimals

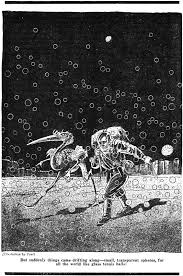

Zendexor: Sounds farcical. But it isn't! If only I could do justice to those stories, A Martian Odyssey and Valley of Dreams... only the trouble is, they're hard to quote from. This is because of their unusual format.

They combine the characteristics of first-person and third-person narrative. The narration is retrospective - in each case we hear a word-of-mouth report, with interruptions and comments. The captain and crew of the first expedition to Mars listen to one of the company - named Jarvis - who has returned to the main ship after scouting around with the aid of an "auxiliary rocket". They hear him out, though the captain is skeptical for a long time concerning Jarvis' interpretation of what he saw.

The format of the tale makes for relaxed reading. We know Jarvis got back safely, the writer having deliberately foregone that kind of suspense which comes from not knowing the fate of the protagonist. On the other hand, the relaxed portrayal, the back-and-forth conversation, the exchange of viewpoints, makes the whole thing more three-D real.

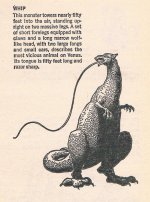

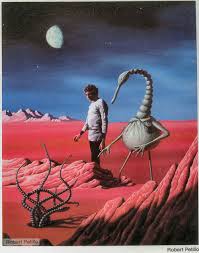

And we do get to feel some suspense regarding Tweel, the vividly described, friendly yet mysterious Martian whom Jarvis befriends after rescuing it (not "him"; Weinbaum's Martians have no sex) - rescuing it from a "dream beast"...

Stid: That ropey "dream beast" - I've met him on a different world. Eric Frank Russell's Mesmerica.

Zendexor: Yes, that one was ropey and hypnotic, too. Pretty much the same, in fact, except that I think the Russell version could walk. If Russell did not read the Weinbaum story, we have a very interesting case of two powerful imaginations focussing upon the same kind of creature... 21 years apart. Makes you wonder if they're on to something...

Anyhow - as I was about to say:

Tweel is a vivid creation. Tweel is not twee. It's all the more impressive because of the way the understanding between it and Jarvis does not go beyond a certain point. Jarvis has made some headway in communication by drawing diagrams of the planets' orbits...

"...I went on with my lesson. Things were going smoothly, and it looked as if I could put the idea over. I pointed at the earth on my diagram, and then at myself, and then, to clinch it, I pointed to myself and then to the earth itself shining bright green almost at the zenith.

"Tweel set up such an excited clacking that I was certain he understood. He jumped up and down, and suddenly he pointed at himself and then at the sky, and then at himself and at the sky again. He pointed at his middle and then at Arcturus, at his head and then at Spica, at his feet and then at half a dozen stars, while I just gaped at him. Then, all of a sudden, he gave a tremendous leap. Man, what a hop! He shot straight up into the starlight, seventy-five feet if an inch! I saw him silhouetted against the sky, saw him turn and come down at me head first, and land smack on his beak like a javelin! There he stuck square in the centre of my sun-circle in the sand - a bull's eye!"

"Nuts," observed the captain. "Plain nuts."

"That's what I thought too. I just stared at him open-mouthed while he pulled his head out of the sand and stood up. Then I figured he'd missed my point, and I went through the whole blamed rigmarole again, and it ended the same way, with Tweel on his nose in the middle of my picture!"

"Maybe it's a religious rite," suggested Harrison.

"Maybe," said Jarvis dubiously. "Well, there we were. We could exchange ideas up to a certain point, and then - blooey! Something in us was different, unrelated; I don't doubt that Tweel thought me just as screwy as I thought him. Our minds simply looked at the world from different viewpoints, and perhaps his viewpoint is as true as ours..."

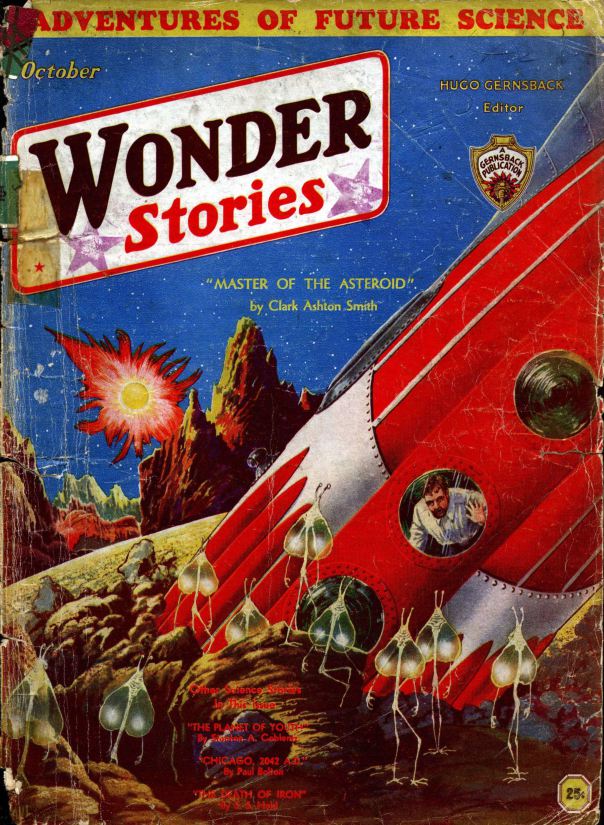

Eric Frank Russell, "Mesmerica" (novella in the linked collection Men, Martians and Machines (1955); Stanley G and Helen Weinbaum, "Tidal Moon" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, December 1938); Stanley G Weinbaum, "A Martian Odyssey" (Wonder Stories, July 1934); "Valley of Dreams" (Wonder Stories, November 1934); "Flight on Titan" (Astounding Stories, January 1935); "Parasite Planet" (Astounding Stories, February 1935); "The Lotus Eaters" (Astounding Stories, April 1935); "The Planet of Doubt" (Astounding Stories, October 1935); "The Red Peri" (Astounding Stories, November 1935); "The Mad Moon" (Astounding Stories, December 1935); "Redemption Cairn" (Astounding Stories, March 1936); "Shifting Seas" (Amazing Stories, April 1937)

For The Mad Moon see Cunning Ionian Slinkers.

For The Planet of Doubt see Phantasmal Uranian shadows.

For The Red Peri see Carnivorous Crystals of Pluto.

For Redemption Cairn see Europan Menu.

For Tidal Moon see Wind-swept, Flood-swept Ganymede.

For Valley of Dreams see Explorers arrive at a desert city on Mars

For the episodic unpredictability of Weinbaum's Mars see Multi-Pocket Worlds.

Gazetteer entry: for A Martian Odyssey, Thyle II.