the sunport vista:

zendexor's

oss

diary

2023

The Samuel Pepys of the OSS...

2023 December 31st:

THANKS TO YOU, READERS

2023 has been a breakthrough-year for Solar System Heritage.

May 2015, eight and a half years ago, was when I began the site. The monthly total of visitors first topped 1,000 in the September of the following year, 2016. It first topped 2,000 in the August of the year after that. Since then, it has only once (February 2021) slipped back below 2,000. On the other hand, for most of the six-year period 2017-22 it stayed in the 2,000's.

There were spurts of greater interest: particularly during September-October 2018, and January-February 2020, with all the excitement surrounding the preparation of the Vintage Worlds anthologies, which pushed the totals up to over 4,000. But each time it went back down again - to the 2,000's, with the occasional 3,000+.

I was getting accustomed to the idea that 2,000-3,000 was the natural numerical limit of this niche, elite, ultra-crème-de-la-crème community of elevated souls.

Then came 2023. During every single month the total of visitors has been over 3,000; in eight of those months it has been over 4,000; in six of them, over 5,000; and in two of them (including this one, which is ending the year on a record total) over 6,000.

Moreover, the increase can't be ascribed to any particular short-term stimulus like that which the anthologies had provided. It must, I guess, be more solidly based, a natural expansion as the word gets around and the site itself grows to provide more of what you, the readers, wish for.

For all your support, I'm grateful: to the silent majority of readers and to the select few of contributors, this year in particular including the anonymous "Lone Wolf" researcher who has provided so many of the popular Guess The World scenes. I expect it's only a matter of time before more such stars emerge in the OSS firmament - if that isn't an invalid mix of solarian and interstellar metaphors...

2023 December 26th:

CELEBRATING VENUSIAN EMPERORS' CORONATIONS

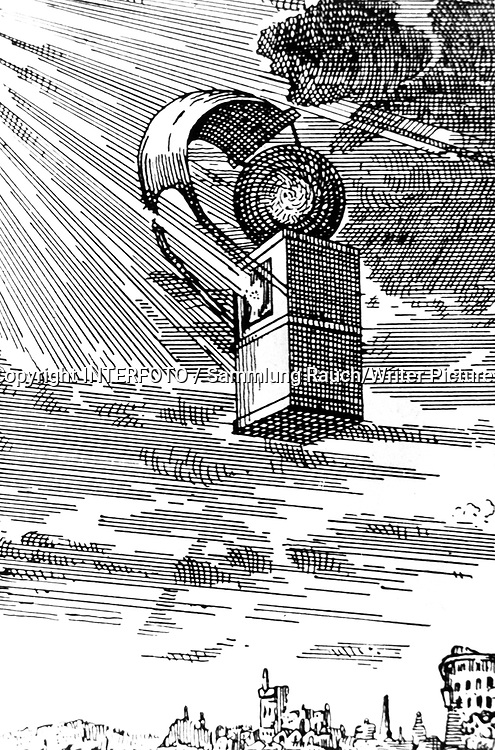

For various reasons, including the fact that this is the season for celebratory moods, and besides that I live in a kingdom which has experienced a Coronation this year, my thoughts have wended their way to our sister planet and an extremely cute idea mooted in the early nineteeth century, regarding the (unconfirmed) Ashen Light.

Franz von Paula Gruithuisen, noting observations made in 1759 and again in 1806 (i.e. after an interval of 76 Venusian years), suggested:

If we estimate that the ordinary life of an inhabitant of the planet lasts 130 Venus years, which amounts to 80 Earth years, the reign of an emperor of Venus might well last for 76 Venus years. The observed appearance is evidently the result of a general festival illumination in honour of the ascension of a new emperor to the throne of the planet.

(For a fuller account, from which I obtained the above quote, see the delightful article by Izzy Ehrlich.)

It was too good to last, and later on Gruithuisen switched to a more humdrum explanation, based on the idea that the Venusians were lighting fires for agricultural purposes.

As Izzy Ehrlich says in her deadpan way, There are objections to both of Gruithuisen's theories, but my point is that you can sometimes find that scientific explanations don't lag far behind fiction in inventiveness.

And it's interesting that even now the Ashen Light is an open question!

You'd think, would you not - considering that Venus is the closest planet to Earth, and what with all the probes that have been sent there - that by this time scientists would have at least decided whether or not the mysterious illumination actually exists.

2023 December 21st:

DETECTION WITH THE TOLKIENOSCOPE

Before we say goodbye to 2023, the 50th anniversary year of the death of J R R Tolkien (1892-1973), I feel moved to say something about him despite the fact that, not being an sf writer, he might be viewed as irrelevant to this site.

What particularly moved me to say what I'm about to say is a comment by John Greer in his Ecosophia blog this week. John is my fellow-editor of the Vintage Worlds anthologies. His blog is something unique, a refreshment for the mind which I look forward to reading every Wednesday. The occultist stuff is usually over my head but the social, historical and philosophical comment is profound and fascinating, and I'm in agreement with 99% of it.

Now for an instance of the 1%...

This week's Ecosophia blog is well up to par, but what I'm focusing on here is what (to me) is a lapse: it's where John refers to what he calls "the strident moral dualism that is the worst flaw of Tolkien’s work".

It's not clear whether he is saying (a) that each character in the story is either wholly good or wholly bad, with no shades in between, or (b) that this dualism applies to the societies in the story, or (c) both.

Point (a) is dealt with by C S Lewis in his review, much more deftly than I could do. I propose here to deal with point (b): the idea that the societies or cultures in The Lord of the Rings are entirely and simplistically either good or evil.

First let me point out that, since a society is made up of individuals, to some degree it cannot be free of flaws if the individuals have flaws. But I concede that such flaws arising purely from individuals are not "systemic", so what about the lack of systemic evil in (say) The Shire or Gondor?

I would argue that if this is what John is criticising, he's right about the fact but he's wrong to call it a flaw. If it were a flaw, it would mean that the book is as boring as the phrase "strident moral dualism" suggests it must be. On the contrary, part of its special fascination lies in what it demonstrates can work in literary terms - and if it works in literature (suggests the whisper in the soul) might it perhaps work in practice? At least, it's worth bearing in mind! And what is this "it"?

Ah, that's the thing that amazes me most, about Tolkien's popularity.

He actually succeeded in a work published in the second half of the twentieth century in portraying - believably - a wholesome culture.

A culture that isn't putrid with sex-addition, slobbish vulgarity and pervy yuck.

Believably portrayed: for the story internally coheres; it's true to itself. Here I am, it says, and you must face the fact of my real-in-my-own-terms existence.

Literature doesn't just amuse us, it can be an instrument of detection, a sort of sensor that indicates truths about ourselves and our moral natures despite the fact that the objects in the story may have no existence in the real world. Just as in a good vampire story we learn - we cannot help learning, if the story works - that good and evil are not simply matters of the will, that involuntary evil is a terrible possibility, so in reading The Lord of the Rings we must take the hint that we DON'T NEED to regard our quotidian cesspit as "normal" and Middle Earth as unrealistic.

It could be the other way round.

And perhaps these comments aren't so inappropriate on an sf website after all - or at any rate on this one, if we view the classic, yuck-free Old Solar System as a kind of Middle Universe...

2023 December 18th:

A TWO-AUTHOR OSS

Quite a few tales have been written in collaboration, but it's much rarer to find a fictional scenario held in common by more than one author writing independently. In fact, right now I can only think of one example, which I'll call "the Barnes-Kuttner universe" or BKU.

This site already has a page devoted to part of the BKU, namely Arthur K Barnes' Interplanetary Huntress series, or at any rate the five tales in the book of that name. At the time I composed that page I thought the book gave us all of that universe. Thanks to contributor Lone Wolf, I now know that this is far from the case.

In an ideal world, I'd immediately get cracking on a full-blown page on the BKU as a whole, but the way things are, with so much else on my plate, the project must be postponed; meanwhile, however, I can at least share with you the data which Lone Wolf has sent me, and from which I learned of the BKU's extent.

The list he's emailed me contains twelve related stories. With the exception of The Seven Sleepers, unavailable online as yet, he has included links to access them:

1. Green Hell by Arthur K. Barnes (Thrilling Wonder Stories, June 1937)

2. The Hothouse Planet by Arthur K. Barnes (Thrilling Wonder Stories, October 1937)

3. Hollywood on the Moon by Henry Kuttner (Thrilling Wonder Stories, April 1938)

4. The Dual World by Arthur K. Barnes (Thrilling Wonder Stories, June 1938)

5. Doom World by Henry Kuttner (Thrilling Wonder Stories, August 1938)

6. Satellite Five by Arthur K. Barnes (Thrilling Wonder Stories, October 1938)

7. The Star Parade by Henry Kuttner (Thrilling Wonder Stories, December 1938)

8. The Energy Eaters by Arthur K. Barnes and Henry Kuttner (Thrilling Wonder Stories, October 1939)

9. The Seven Sleepers by Arthur K. Barnes and Henry Kuttner (Thrilling Wonder Stories, May 1940)

10. Trouble on Titan by Arthur K. Barnes (Thrilling Wonder Stories, February 1941)

11. Siren Satellite by Arthur K. Barnes (Thrilling Wonder Stories, Winter 1946)

12. Trouble on Titan by Henry Kuttner (Thrilling Wonder Stories, February 1947)

(The Seven Sleepers, by the way, is the adventure in Interplanetary Huntress with the title Almussen's Comet.)

Note the two stories called, identically, Trouble on Titan! It would appear that Barnes and Kuttner slipped up in failing to liaise about titles. At first I couldn't believe in such a blunder. Surely, thought I, one of them must be a typo for "Triton" in Lone Wolf's list. But no - an online check of the original magazine version shows Titan for both.

For that matter, there's also a novel by Alan E Nourse called, likewise, Trouble on Titan. Well, the alliteration is tempting...

2023 December 12th:

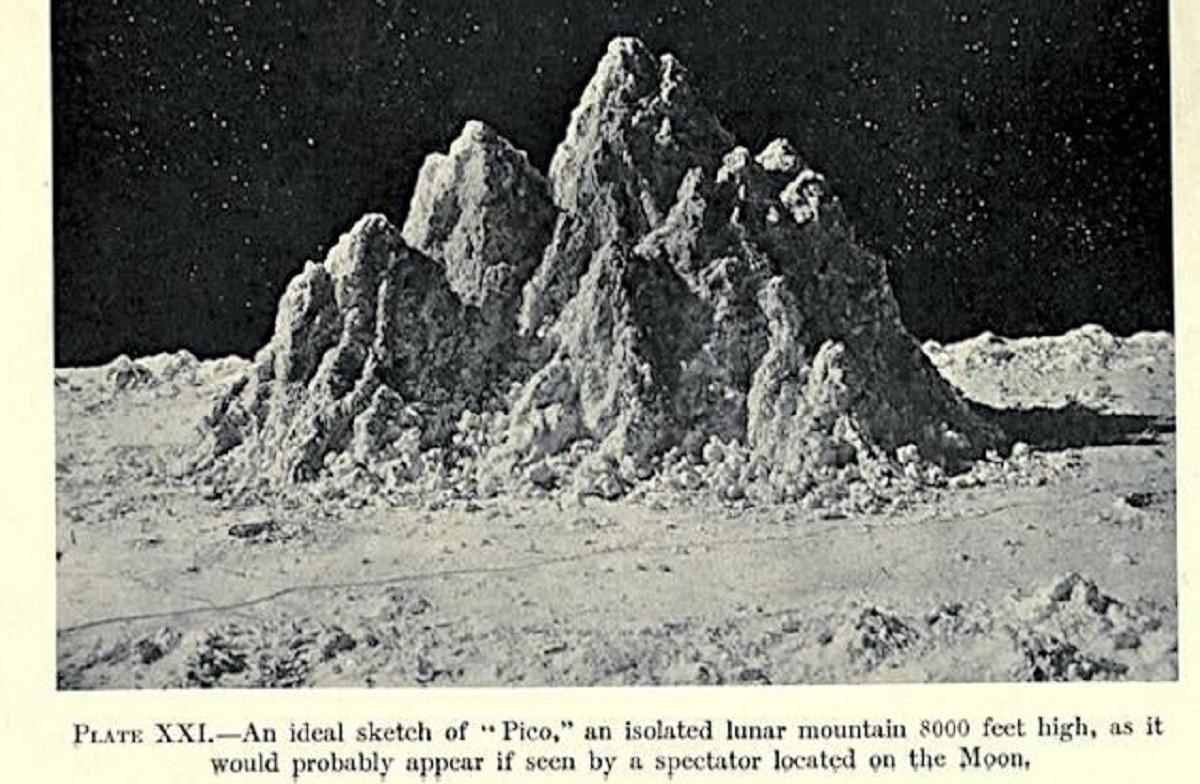

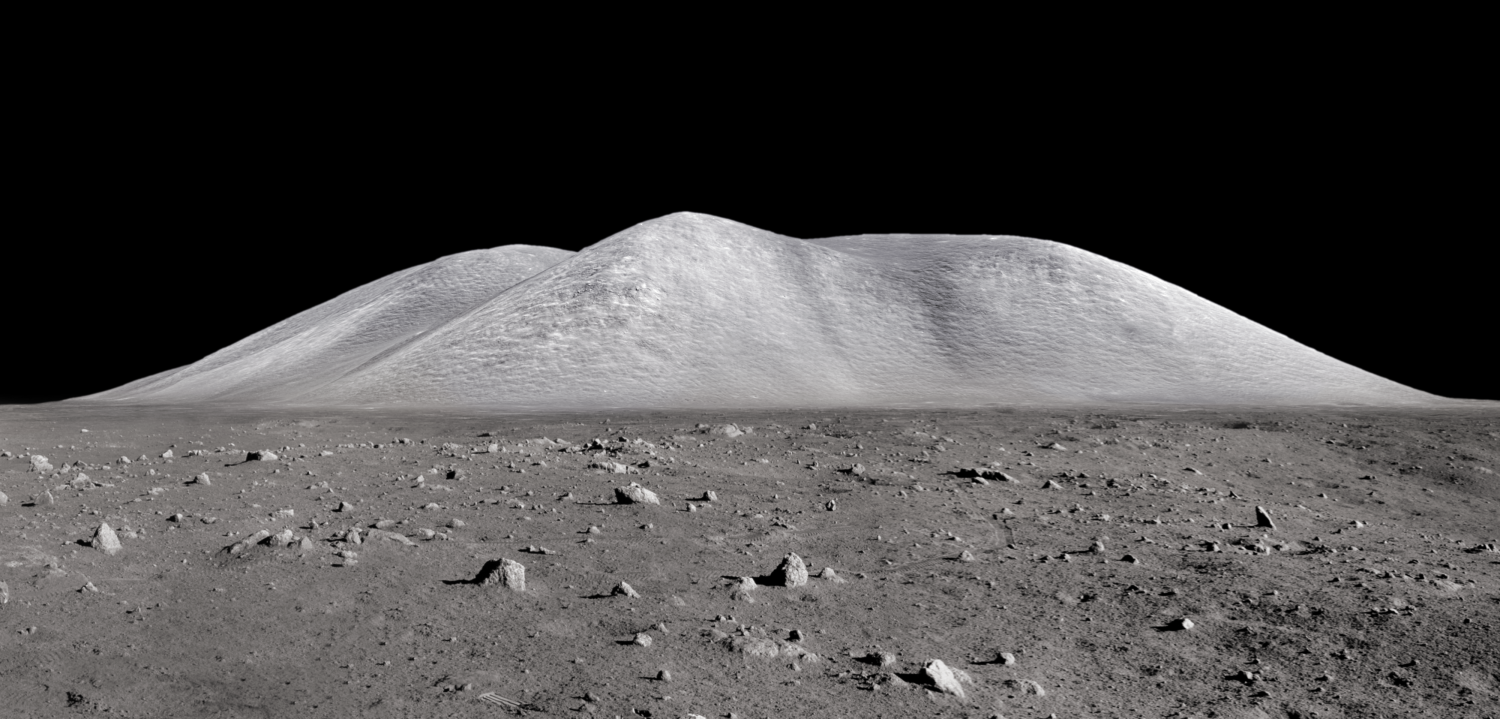

RUGGED VERSUS UN-RUGGED MOUNT PICO

Currently, if you search on the Web for Mount Pico (the one on the Moon, not the one in Portugal), you are likely to find references to an interesting comparison between a 1874 illustration and one derived from space-age imaging.

Mons Pico is a dramatic solitary mountain in the northern part of the Mare Imbrium. The peak and its surround feature in the climax of Earthlight, the 1955 novel by Arthur C Clarke about the build-up and the short course of an interplanetary war. (For some reason, it seems that the Mare Imbrium area is, with the possible exception of Tycho, the most written-about zone on the Moon.)

Flick your glance between the 1874 and the modern versions and you'll see the obvious contrast in ruggedness.

Oddly enough for a nostalgic fellow like myself, I actually prefer the modern version, with its relatively uncluttered and majestic smoothness. In my view the Moon has been far less of a let-down than any other Solar System body during the de-enchanting Age of Space. It's a world that does not need the charms of organic life to develop its mystique - though admittedly it would be great to discover those lunar plants which Arthur C Clarke thought possible in 1955, or the insects or small animals such as those which observer William H Pickering in 1924 suggested were moving across the floor of Eratosthenes...

Back to the ruggedness issue, though: it seems likely to me that the sharpness of lunar peaks in old imaginings was not just due to an urge for the picturesque. I suspect that the assumption which underlay such portrayals may have been that low gravity implies vertical elongation. That was C S Lewis' idea in his depiction of the sharp Martian mountains in Out of the Silent Planet.

Well, why not? It seems logical. However, it seems that things don't actually work that way. The reason (so instinct tells me) may be that low gravity just encourages a landscape to be jumbled and irregular, not necessarily minaret-like.

Architecture would be another matter. Bradbury might have been right with his fragile Martian towers... if any Martians had actually existed.

2023 December 1st:

HOMAGE TO BARSOOM - "SLEEPING SILKS AND FURS"

It's very cold at the moment where I live, in Lancashire in the North-West of England. Cold for me, anyway - whatever a Russian or Canadian might think.

I've made a handy discovery, which is that, in my view, when lying down for an afternoon rest, four old cardigans plus a dressing-gown arranged over me is actually much more comfortable and convenient than a blanket, duvet or throw, and less stifling and a lot less expensive than to rely on the central heating or electric fires. To give the arrangement glamour I have taken to referring to it as my "sleeping silks and furs". Now my wife Mary, who has never read the Barsoom books, likes to use the phrase too.

All credit therefore to Edgar Rice Burroughs for making his version of Martian culture so vivid that its usefulness extends thus to Jasoom.

Also, it gets me thinking about the subject of the Barsoomian climate. Mars must get only about half the solar heat that we do, yet the Barsoomians go around attired in next to nothing, except the folk of Okar and other polar lands who do wrap up somewhat more. On the face of it, this is a glaring mistake by the author, yet I seem to remember that somewhere or other he does make the point that the Martian sky, being usually cloudless and clear, admits more of the sun's rays than does the atmosphere of Earth, which is why it's quite warm there. Just about the thinnest excuse one could dream up; yet the important point is, in such cases, that the excuse is made at all.

That's what separates science fantasy from "mere" fantasy: the excuse-dimension. It can be as implausible as this one is, yet that perfunctorily respectful nod suffices for the retention of genre-membership.

2023 November 23rd:

LORE OF AN ISLAND ON PLANET THREE

At work on the new Gazeteer page and searching for useful references I came across a very attractive link for the locations in The Day of the Triffids. (If any of you have not read read John Wyndham's 1951 classic, you've got a treat in store.)

As a Briton I already knew that the main places in the book are real, but for those of you who can't be expected to know this, the news may satisfy some extra curiosity.

Personally I prefer terrestrial locations in fiction to be real whenever it's reasonable for them to be so. For instance I like it that Providence, Rhode Island, exists, and isn't just invented by H P Lovecraft! Trouble is, one can't claim the same for Arkham and Innsmouth...

Anyhow, one thing is for sure: planet Earth is amazingly real, fantastic though it seems.

2023 November 17th:

VENUS ISN'T JUPITER

Tex stirred uneasily where he lay on the parapet, staring into the heavy, Jupiterian fog. The greasy moisture ran down the fort wall, lay rank on his lips. With a sigh for the hot, dry air of Texas, and a curse for the adventure-thirst that made him leave it, he shifted his short, steel-hard body and wrinkled his sandy-red brows in the never-ending effort to see.

This is the opening of Leigh Brackett's Dragon Queen of Jupiter (Planet Stories, Summer 1941).

Straightaway one can sense that something is wrong with the tale's setting. Badly, irretrievably wrong. Firstly the adjective isn't "Jupiterian", it's "Jovian", and you'd expect a great author like Brackett to know that. ...All right, another great author, ERB, used "Jupiterian" in Skeleton Men of Jupiter, but that was John Carter speaking, and maybe his education was lacking. Besides - here we proceed to the second cause of unease - this fellow Tex seems not too bothered by the 2.64 Earth gravities he must have been experiencing on the surface of the giant planet. Again, ERB got round this, but he did give a reason - he didn't just ignore the problem; whereas this Dragon Queen story just carries on regardless.

The colourful Planet Stories cover intrigued me and because I hunger and thirst after Giant Planet OSS fiction, I hoped to find redemptive features of this "Jupiterian" yarn. No such luck. Plainly, it's not Jupiter. If anything, it's Venus.

Somebody cursed because the underwear never dried in this lousy climate. The heat of the hidden sun seeped down in stifling waves...

You would hardly find the Sun stiflingly hot out Jupiter way. Swamps, mist, heat... it's Venus if it's anything.

And lo and behold, upon searching online I found that in all later re-issues of the tale, it IS Venus!

I'd very much like to know the editorial history of this interplanetary blunder, and what degree of involvement the author had in it. A pity she didn't write a proper surface-of-Jupiter story, or, if she baulked at the gravity issue, a surface-of-Saturn story. The history of sf contains enough swampy-Venus stories, after all.

However, to end these reflections on a positive note: at least the whole farrago demonstrates the limits of the possible in OSS settings. You can flout science a lot, but not infinitely much, and, more to the point, you can't flout the mood: an OSS world has a character of its own, flexible but with a breaking-point beyond which the story won't work. And so the literary amendment-ray of the Planet Police has restored order:

Tex stirred uneasily where he lay on the parapet, staring into the heavy, Venusian fog....

2023 November 11th:

LEAVING WELL ALONE

In his unputdownable non-fiction book Profiles of the Future Arthur C Clarke is his bullishly optimistic usual self with regard to the benefits of knowledge. Whether or not Man measures up to his potential, the message is clear: it's good to try.

In one of his best novels, though, the mood is somewhat different. Childhood's End is the odd-man-out in the Clarke oevre, like The Island of Dr Moreau in Wells' (I only thought of this comparison today). The tone is basically sombre, although (in the Clarke novel, not the Wells one) we do find some lightness and humour.

It is in the attitude to the Quest for Knowledge that they strike (for me) similar notes.

The Overlords who come from the stars to impose their benevolent rule on Earth have an ultimate and an immediate motive. The ultimate motive I won't spoil for those who haven't read the book. The immediate motive is the one that is relevant to what I'm arguing here. To quote the chief Overlord's words when he finally explains:

"...All down the ages there have been countless reports of strange phenomena - poltergeists, telepathy, precognition - which you have named but never explained. At first Science ignored them, even denied their existence, despite the testimony of five thousand years. But they exist and if it is to be complete any theory of the universe must account for them.

"During the first half of the twentieth century, a few of your scientists began to investigate these matters. They did not know it, but they were tampering with the lock of Pandora's box. The forces they might have unleashed transcended any perils that the atom could have brought. For the physicists could only have ruined the Earth: the paraphysicists could have spread havoc to the stars.

"That could not be allowed. I cannot explain the full nature of the threat you represented... Let us say that you might have become a telepathic cancer, a malignant mentality which in its inevitable dissolution would have poisoned other and greater minds.

"And so we came - we were sent - to Earth..."

Quite profound, for Clarke. (I regard him as a great writer but a shallow philosopher.)

Larry Niven's The World of Ptavvs ends with the reluctant concession that some scientific marvels are too dangerous to allow in our culture - hence the suppression of the thrintun thought-amplifier helmet, lest it be used to establish a tyranny. I like the scene in which it is stipulated that the helmet be thrown into the atmosphere of Jupiter - the statesman who insists upon this step also says he would have preferred to have been dropped into the Sun, but Jupiter would have to do. (I'm fascinated by the implication of this doubt that even to drop something into the depths of Jupiter might not be to lose it for all time. How not? Would the churning clouds possibly bring it to the surface again? Or might men eventually invent force-fields that would allow them to explore the Giant Planet at any level?)

Then there is Asimov's tale, The Dead Past, in which the invention of a time-viewer turns out to be a disaster. Another dark story by a writer who is usually a sunny optimist as regards the benefits of Science.

How can knowledge be bad? Well, remember the saying, "Knowledge is power". Then perform the substitution and ask: How can power be bad? Answer: quite easily.

And it's not just that we as a species are corruptible; it's also that we may be insufficiently tough to endure the secrets of the universe. This thought brings us finally to H P Lovecraft. Again and again in his best stories his narrators plead for the safety of ignorance. For if you know too much, the knowledge may destroy you.

...If that abyss and what it held were real, there is no hope. Then, all too truly, there lies upon this world of man a mocking and incredible shadow out of time.

That speaks to me profoundly. You may ask why I, a Christian, am such a fan of the atheist Lovecraft who never tired of belittling Man's place in the cosmos and denying any meaning to life. My answer is: the Lovecraftian view is not the ultimate truth, but I suspect that there are vast stretches of reality where it applies: the non-ultimate but formidable forces of night and chaos.

On that cheery note, let me finish by saying that in the next Roll Off A Tangent YouTube podcast I and my team-mates will be discussing Lovecraft's The Shadow Out of Time.

2023 November 9th:

MATURE MARTIANS

With a view to spotting literary overlaps which develop the characters of worlds, doubtless I've already (somewhere, on this vast site) compared two different authors' accounts of Martian cultures which, while far from primitive, nevertheless reject the idea of space travel or the technological "rat race".

This pair of examples comprises C S Lewis' Malacandrians portrayed in Out of the Silent Planet (see my brother's overview of that novel), and Heinlein's enigmatic, formidably mind-powered Martians in Red Planet.

To be accurate, in Lewis' account it's not so much the Martians themselves but their invisible ruler the Oyarsa, who rejected the option of space-migration as an escape from the primordial cataclysm which rendered most of Mars' surface uninhabitable. Still, the renunciation theme is clear.

Now, so far as I can remember I haven't yet associated with these two a third example, that of the denizens of the isolated city in Leigh Brackett's The Last Days of Shandakor. I ought to have thought of it before. It fits well.

It came to my mind recently because I'd put an extract from the Brackett tale in Guess The World (see A mysterious fortress city on Mars): thinking further about the story I realized that here again is the theme of wise, intelligent Martians who can't be bothered with much technology because their minds dwell on higher things.

"...we humans of Earth have outstripped yours a million times. All right, you know or knew some things we haven't learned yet, in optics and some branches of electronics and perhaps in metallurgy. But..."

I went on to tell him all the things we had that Shandakor did not. "You never went beyond the beast of burden and the simple wheel. We achieved flight long ago. We have conquered space and the planets. We'll go on to conquer the stars!"

Rhul nodded. "Perhaps we were wrong. We remained here and conquered ourselves." He looked out toward the slopes where the barbarian army waited and he sighed. "In the end it is all the same."

So there you are: the third example. When one gets to three, I reckon it must mean something.

As for what it means: it probably springs from the logic of that sub-genre of OSS tales which portrays a Solar System where space-travel is entirely or mostly in the hands of Terrans. Something has to explain the fact of Earthlings being spacefarers to the exclusion of other native System cultures. The easiest answer is that of the natives' renunciation, stemming from their different scale of values.

The Jovians might be an exception: their world's gravity, rather than their psychology, might be the obstacle to their development of space-flight. But apart from that, we could just say that Terrans are uniquely restless and - who knows - immature!

2023 October 31st:

LAWLESS SCIENCE: STYLE AND MOOD

Thinking of the recurrent "realism" issue, I'd like to mention some recent examples that have shouldered forward to claim attention.

I shall start out in the stellar neighbourhood and then work my way in to the OSS heartland.

To fill gaps in the Fictional Dates timeline I have recently been adding reference to some of Lovecraft's tales, and of these the latest that sprang to mind was Beyond the Wall of Sleep. The chief value of the story for the OSS consists in its exquisite CLUFF regarding the "the insect-philosophers that crawl proudly over the fourth moon of Jupiter." of Callisto. But right now I wish to mention something else.

In the climax of the tale, we read of the release of a cosmic being from imprisonment inside the body of a patient in a terrestrial mental home, and the almost simultaneous appearance of a nova close to Algol: not just line-of-sight close, but really close, according to a message from the entity. And the nova is said to stem from the entity's release: this despite Algol being light-years away, so that any nova in that region would not be seen on Earth for many years after its birth.

Well, says I, who cares? It ought to be child's play for a veteran OSS excuse-maker to think up an explanation. Spiritual events, psychic events, or whatever one calls them, perhaps do not obey the law forbidding superluminal velocity. Or maybe it's not velocity at all but instantaneousness. Hence we could have psychic explanation that performs the same sort of function that the more technological one does in James Blish's A Case of Conscience, where we find another instance of an explosion contemporaneously witnessed at stellar distances.

The point is, however thin the excuse (and I'm not sure it is thin here), the act of bothering to make it shows respect for the role of science in science fiction. Sure, it's not hard science. But here's another thing:

Even "hard science" sf authors seem at times to be straining at the restrictions which they believe in. I'm reminded of this by some recent Guess The World entries set on Europa and Saturn.

The extract from Clarke, which I've titled Light-seeking creature on Europa, and that from R L Forward, which I've titled Jet-powered inhabitants of Saturn, are both from the pens of extremely "hard" sf writers, yet what really motivates them, I suspect, is the romantic longing for a version of our solar system that harbours extraterrestrial life.

Perhaps they might have objected that their fiction is none the less hard-sf for being also the embodiment of hope. They might have cited calculations that show that the energy budget of Europa (with energy from tidal forces due to proximity to Jupiter) and that of Saturn (due to gravitational contraction of the gas giant) are sufficient to provide for the evolution of life.

Well, perhaps (though I doubt it). But if the authors are not romantic, that still leaves the reader with the option...

2023 October 21st:

CYRANO'S GLIMMER OF SOLARIAN SF

My edition of Cyrano de Bergerac's L'Autre Monde (1657) is the translation by Geoffrey Strachan in the New English Library paperback "SF Master Series", and from the date I wrote in biro on the inside cover I see I purchased it on 15th February 1980. So long ago - and I never had a proper crack at reading it until a couple of days ago, when it occurred to me that I might find something appropriate for Guess The World therein.

Cyrano's narrator visits both the Moon and the Sun. Most of the tale is jokey, witty and an exercise in philosophical playfulness with hefty doses of satire - lacking any breath of the true sf sense of wonder. That's my verdict on the entire portion focused on the Moon, and it's why I let the book lie fallow in my collection, untouched on the shelf for over four decades. But now I know a bit better. When the adventurer goes to the Sun, although I find that most of this part is at the same sort of level of chit-chat as the lunar section, I also find a few precious literary moments of something more - and yes, appropriate for Guess The World: see The luminous countryside of the Sun.

I'd like to suggest, moreover, that there's something in Cyrano's tale which could point to the future of Solarian SF. It springs from the distinction the book makes between brighter and darker areas on the Sun (inspired by sunspots, I suppose):

"You must know that being inhabitants of the pellucid part of this great world, where the principle of matter is to be in action, we are bound to have much more active imaginations than those of the opaque regions, and bodies composed of a much more fluid substance.

"Once one supposes this, it inevitably follows that our imagination, encountering no resistance in the matter of which we are composed, can arrange it at will, and, having become the complete master of our bodies, manoeuvres them, by moving all their particles, into the arrangements necessary to constitute the objects it has pictured in miniature..."

This is mind-power, which (updated into more modern language) could be the basis of a plausible account of life on the Sun. And if this idea were pursued, it could zoom ahead into visions of solar landscapes translated into forms relatable to humanity, the only limits being artistic rather than scientific credibility. For what can science say to delimit the power of the mind?

2023 October 17th:

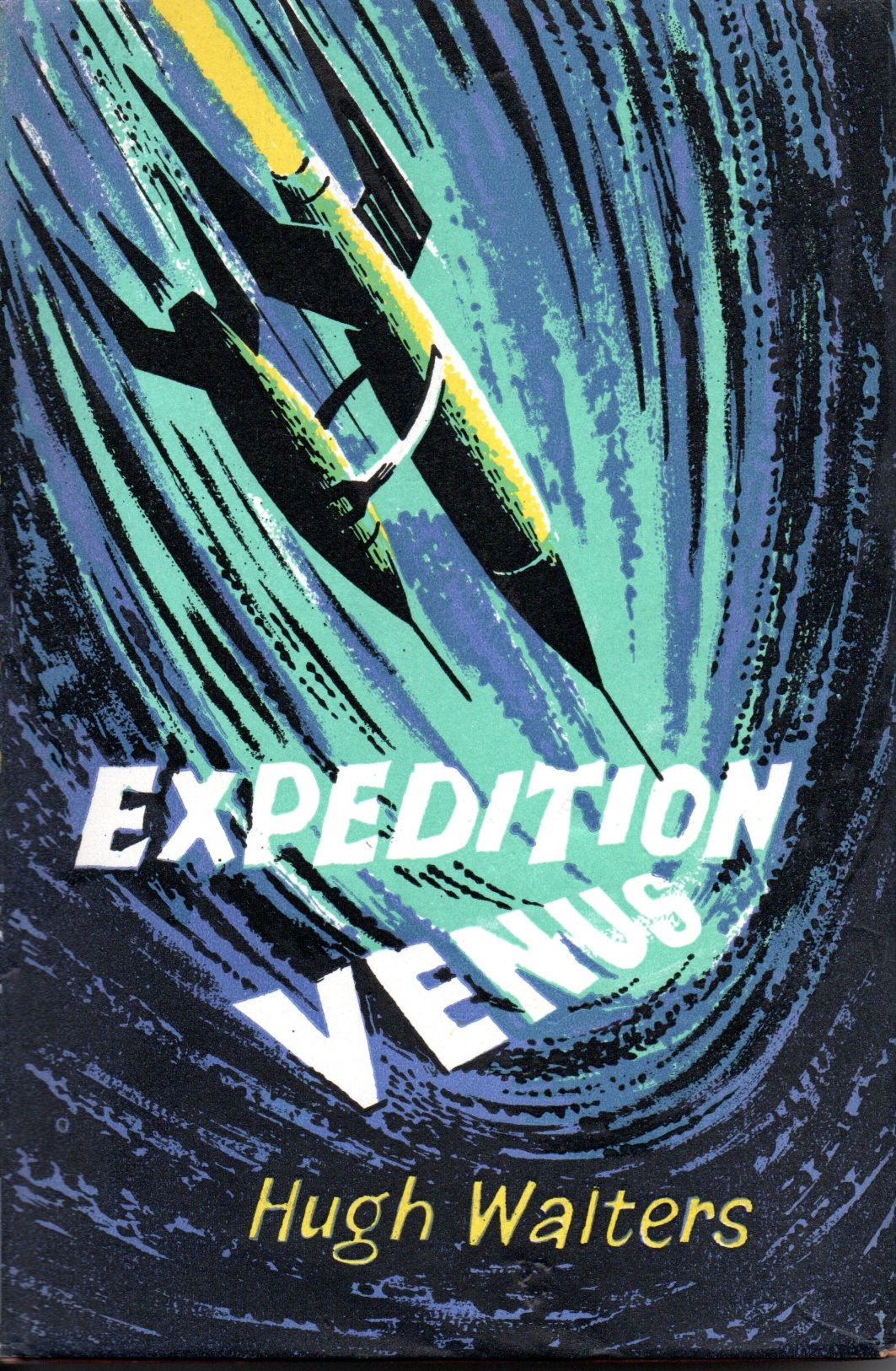

HUGH WALTERS AND THE RUN-UP TO INTERPLANETARY VOYAGES

Having chosen a few paragraphs from Expedition Venus for yesterday's Guess The World, I got to thinking about why that particular book succeeds so well for me. It's not an easy thing to explain. In the story, the time actually spent on Venus is measured in minutes, and the rocket crew don't get any view of the landscape. Not a promising scenario, one might think.

Yet this juvenile novel made a great impression on my young self, and not just because of the superb cover art by Leslie Wood.

Context must explain it all. Expedition Venus is the fifth novel in Walters' series, and though like the others it can be read on its own it gains from the accumulated, architectonic build-up provided by its predecessors.

The author devoted four books to manned spaceflight in the Earth-Moon system before extending his saga to the planets. Thus: Blast Off at Woomera (1957) is about a near-Earth flight; in The Domes of Pico (1958) an astronaut swings around the moon; Operation Columbus (1959) features the first moon landing; Moon Base One (1960) is about a longer stay.

In these four adventures, the motive for the space program is not international rivalry so much as a fear-driven urge to investigate a hostile alien presence which is bombarding the Earth with harmful radiation from the Moon. However, Expedition Venus (which came out in 1962, after a two-year publishing gap) doesn't mention the hostile aliens at all. They seem to have disappeared as mysteriously as they came, and as far as I can recall they are never again mentioned in later books in the series (I must confess I haven't read them all - not because I don't want to but because the ones I failed to obtain have become so rare and expensive that I can't get them now). The Venus flight is spurred by a new motive: a lowly life-form, a mould picked up by an automated Venus sample-return probe, is threatening all life on Earth, and the only hope of saving mankind is to find some natural enemy on its world of origin by which the plague might be controlled.

Be all that as it may, I wish to stress that the impression given to the reader in all these books is that space expeditions are anything but casual or individualistic. They are indeed high adventure, but as much attention is given to their preparation as to the heroism they require after blast-off.

Moreover, this sense that the voyage itself is a superstructure on top of a vast collective effort applies to the structure of the series as a whole - at least, to that part of it which I am considering. And so, my young self was all the more excited at seeing the library's copy of Expedition Venus, after the preparation I had undergone via the four earlier adventures.

2023 October 16th:

LOOKING AHEAD WITH EXCITEMENT TO.... 1981

Once as a youngster when in my local library (that of Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire, England) I saw a poster on the wall giving information about plans for urban development several years in the future... the completion date being 1981. Wow, thought I: that date has a really futuristic ring.

Somehow the emotional message "1981 = exciting future" has got stuck in me, a recording that won't stop playing.

And if 1981 is way out in the future, what about 2023?

The beauty of being an sf fan is that if one scenario doesn't work out, you can pick another. The Clarkeian future hasn't happened and from where I'm standing it's too late for it ever to happen, because even if we get to Mars and further, we're no longer the same human race as existed when I was a space-struck lad. HOWEVER -

Zip, along comes a different scenario! Not the cleanly inspiring future of The Sands of Mars, but the weird macabre future of countless other sf visions. Decline can be as colourful as progress; in fact it is progress, albeit in a different direction.

Towards Clark Ashton Smith's Zothique cycle, perhaps - in the long term.

No, actually, it won't be as cuddly as that - I was just kidding.

But to get back to the topic of 1981: that was just one year on from the date in which was set Clark Ashton Smith's Master of the Asteroid. And I've also imagined, with a habit of mind that has become traditional with me for some reason, that the action in The Immortals of Mercury took place in 1981 itself, though the tale doesn't say so. Somehow it seems the right date for it.

Dates, it seems, have personalities; even more so as the years go by and those in the real continuum catch up with the ones written about fictionally in advance.

For example it's not so long now till 2025, when the voyagers in Burroughs' The Moon Maid reach their destination, while NASA is making its own bid to return to Luna at more or less the same time!

2023 October 14th:

THE WSQ ARCHIVE - FOUND!

Further to my Diary entry of two days ago, I was happy to get the following email from ace GTW-contributor Lone Wolf concerning Wonder Stories Quarterly:

You mentioned in the OSS Diary that the issues of WSQ from 1930 online have disappeared and since those Neptunian stories seemed interesting to read, I tried to search for them and found them here:

https://comicbookplus.com/?cid=2607

This site (Comic Book+) is one of my sources, not so abundant as Internet Archive, but sometimes I find here some rare issues, that I haven't been able to find elsewhere. The problem is that they are in format cbz, which I cannot open on my laptop. I used to download them and then convert them into pdf online, but for some reason I cannot do this now (the connection breaks if I try to upload the files to the online converters), so now I can only read them online. So I too live in fear that they may disappear in some moment...

I gave it a try and it seems my laptop is more kindly disposed to the link - it has worked for me. So, for the time being at least, I can get to WSQ's 1930 issues, thankfully.

This whole topic inspires me to go into old-codger mode and share some reflections about access to literary treasures.

I well remember, as a lad (I was born in 1954), being almost entirely dependent for my sf reading material upon a couple of local bookshops in Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire. Occasionally I might go to London (half an hour away by train) and even more occasionally Brussels (we'd take the ferry across the Channel once every year or two to visit my Belgian grandmother, and the big shops in Brussels had a fair quota of English-language books); but mostly I relied on W H Smith and Woods of Sarratt, in Hemel town centre.

It was in Woods that I was able to purchase the three Burroughs paperbacks which for years were my only finds among his planetary novels: Carson of Venus, A Fighting Man of Mars and John Carter of Mars - the latter being a made-up title for a volume comprising Skeleton Men of Jupiter and the non-canonical John Carter and the Giant of Mars.

Like countless other young readers must have been, I was mind-blown sky-high by these adventures, and yearned for more. The other titles were listed in the introductory pages so I knew they existed. I lost no time in ordering them from Woods.

After that, I kept going back to the shop, to ask if they had arrived. In the end the bookseller said, "I don't think they're coming". In those days I didn't understand about books going out of print. I suppose that even in those dark days there were book-search organizations, but I didn't know that then, and the man at the shop didn't tell me.

Years afterward I did find out (I think from an ad in one of the British Science Fiction Association magazines Vector or Matrix) that there was a shop in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, called Fantast (Medway) Ltd which sent lists of available second-hand sf books one could order from them. And wonder of wonders, at last I was able to order the other Barsoom and Amtor titles. I remember the stunning day when a package arrived with maybe a half-dozen of the chronicles of Barsoom!!

Nowadays, of course, it's easy: just go to one of the big online second-hand bookstores and search for a few moments and you're home and dry. Eh, you youngsters don't know how lucky you are!! (Solemn shake of head.)

However, a note of warning for the future. It would not astonish me if in general the supply of books at reasonable prices were to run low. Just as there was a time when you could buy Impressionist paintings easily, and then after a while you couldn't... for how can it be otherwise? If good stuff goes on and on not being reprinted, even the second-hand copies must eventually become scarce.

I'm not trying to depress you all; just suggesting you may need to hunker down for the dark age.

2023 October 13th:

STAPLEDON, BESTER, AND RESCUE BY THE WILL

During a breather between chapters of a long epic I thought I'd sketch out possible connections between some of the themes to be found on this site. What follows here are notes to invite comment rather than a full-blown article.

My remarks on the kallomantle a couple of days ago in this Diary were focused on what I regard as an unconscious, automatic process whereby past cultures acquire an immortal posthumous aura which is additional to, and immune from criticism of, what the cultures used to be during their mortal lifetimes.

But this theme can shade into something more deliberate. If true reality-engineering is ever achieved, some of the psychic nuts-and-bolts of the kallomantle may well have to form a part of it.

Alfred Bester's great short tale Disappearing Act has the theme of wounded soldiers, hospitalised during a horrific future war, who learn to disappear into some alternate reality which they create themselves. Probably they don't know how they do it - but they do it. Olaf Stapledon in his history of mankind's future, Last and First Men, has the enormously powerful and advanced Eighteenth (and Last) Men making backwards contact through time to learn some primitive vigour from the First Men, that is to say ourselves, leaving the reader with the suggestion that the horrors of the past are redeemable through vision and contemplation. And my own frequently-expressed opinion (si parva licet componere magnis) that the literature of the Old Solar System, in swathing the worlds with associations of story, gifts them with something genuinely intrinsic to their character, is a sort of mystic fun that might count as a light-hearted prelude to a future breakthrough in the moulding of reality.

Risky, though! I'm reminded of Stephen King's 11.22.63, in which (spoiler alert) the repeated attempts to go back in time to rescue JFK from the assassin's bullet - with the idea that history might thus be spared the Vietnam War - succeed but only at the cost of dangerously weakening the fabric of reality. The same theme of reality change being overdone occurs in Ben Elton's Time and Time Again, where the object is to prevent World War One, and the attempt to murder Franz Ferdinand at Sarajevo is indeed foiled, but the price is unexpectedly high.

Maybe it's all right if done in moderation. To quote from Keith Laumer's Knight of Delusions:

"...I thought to frighten you, make you amenable to my wishes - but instead you seized on my own sources of energy and added them to your own. As a result, you've acquired powers I never dreamed of - fantastic powers! You'll rend the very fabric of the Cosmos if you go on!"

"Swell; it could stand a little rending..."

2023 October 12th:

NEPTUNIAN DIFFICULTIES

I thought I'd revisit the online archive of Wonder Stories Quarterly from which, some years back, I had gained access to the two Neptunian adventures by Henrik Dahl Juve, which appeared in the Summer and Fall issues of WSQ respectively. I well remember how hugely exciting it was for me when I learned that the archive had become available, as for decades I had longed in vain to get hold of the tale depicted so fascinatingly by Frank R Paul in his magazine cover for that Summer 1930 issue (see Neptunian Allure).

I read both tales and from them had obtained material for the discussion in Neptunian Allure; sometime later, The Monsters of Neptune provided a scene for a December 2017 Guess The World. Now my idea was to choose some excerpt from the sequel, The Struggle for Neptune, as part of my continuing efforts to stay "ahead of the game" in the matter of ensuring a steady supply of GTW scenes.

I did not expect any problem. Yet today when I tried to access WSQ for 1930, it was not available! Issues for the following year are online, but not 1930.

Why should availability fluctuate like this? Can a story be copyrighted after having been in the public domain? I don't know. What I do know is that I shall no longer take the blessings of archival access for granted...

2023 October 11th:

THE GREATEST TERRAN RPG

Among the nine classic planets of the OSS, Earth is the one whose foibles we are naturally apt to take for granted, but every now and then it's fun to ponder them objectively... A noteworthy, though mostly unacknowledged, phenomenon of life on our planet is the kallomantle.

An aura, a field of power detectable by the emotions in the form of a retrospective glow, the kallomantle [κάλλος ("beauty") + mantle] can perform some weirdly unexpected feats. It can belatedly endow historical periods and situations with a glamour which would have been unrecognizable to those people unlucky enough to inhabit the said periods and situations. But that's not to say the phenomenon is an illusion. It is absolutely real: only, it is a late-flowering reality.

"Print the legend."

"Print the legend."Thus, those thinkers who debunk Merrie England or the Wild West or whatever, by pointing out how grim and sordid those scenarios actually were, are missing the kallomantling point, because in each case the end of the actual historical period which the term denotes is not the end of its story; indeed its career has hardly begun, for the "posthumous" legend of an age is every bit as intrinsic to it as is its completed portion of literal chronicle, and furthermore gives it its scope, now without time-limit, to grow its full meaning: legends are immortal, and the last word is the winning word. So far, I have not mentioned role-play, but now I shall try to explain the connection.

I have noticed, perhaps especially with idealistic youngsters, but with quite a few older folk too, a reluctance or maybe an inability to be proud of their country, because they are understandably ashamed of the dark deeds in that country's history. Possibly related to this reluctance is the idea that patriotism implies some sort of attitude of superiority. The result is a revulsion from the whole idea - a revulsion which stems from the best of motives, but which in my view is based on a misunderstanding.

Every one, or almost every one, of us Earthlings is the subject or citizen of some country. All these countries have some character, as unique as a colour is unique, or a language, or a species, or a planet. All countries, old and new, are embodied sagas, whose episodes, dark and bright, become swathed with the glow of the kallomantle. And we, individually, are characters in these sagas.

Patriotism is role-play. It is the great game we've all been born into, and in which we are privileged to have been given the opportunity to play our allotted parts.

Jasoom sure is a splendid planet.

2023 September 27th:

ORTS - 2: THE MARCHING MOUNTAINS OF PLUTO

"We are as good as dead!" yelled Tharb, the hairy Plutonian's big phosphorescent eyes dilated with terror. "Listen to that!"

Curt became aware of a thunderous, cracking, crashing sound that seemed growing louder and nearer by the minute.

"The Marching Mountains!" Tharb howled. "We fell right in their path!"

Edmond Hamilton in Calling Captain Future thus plonks his hero in front of the speeded-up glaciers which eternally circle the frigid ninth planet. What their source of energy is, we are not told, as far as I can recall. Certainly this is one of the most over-the-top scenes in the entire C.F. canon, which is replete with OSS extravaganzas. However, the Marching Mountains are not completely unrelated to the real Pluto, as I propose to demonstrate...

Stid: I reckon, Zendexor, that you're as over-the-top as Captain Future.

Zendexor: I try, at any rate. It's my job. Someone has to perform the altruistic task of reassuring the inhabitants of the RSS that the higher OSS dimension remains imaginatively contiguous...

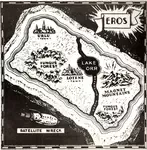

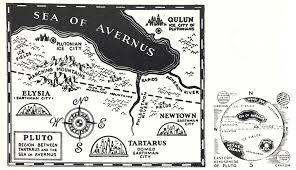

First, have a look at the following map, which illustrates the terrain described in Calling Captain Future (according to J B Post's Atlas of Fantasy it appeared on page 113 in the spring 1940 issue of C.F. magazine).

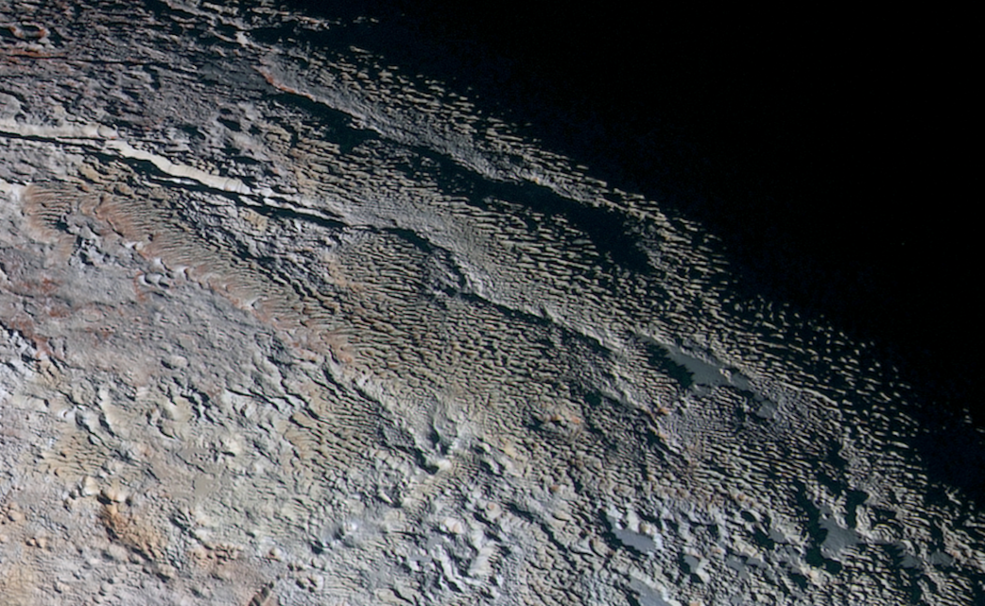

...and now this, which is from How does ice flow on Pluto? by Vanessa Chapman, writing in Space Australia News, 12 August 2020:

Stid: The article admits there's movement on Pluto - but not at marching speed! The comparison you're trying to make is somewhat ridiculous, Z old man.

Zendexor: Ridiculous only if you go in for an arithmetic comparison, for instance if you were to graph the two rates of speed on a steady, linear axis. But if you were to adopt a logarithmic scale, which can bring vastly different numbers closer together...

Stid: I give up, Z.

Zendexor: I was hoping you would. The kind of comparison which an ORT allows is necessarily faint - but that's what hauntings tend to be like, after all.

2023 September 23rd:

ORTS - 1: THE POLES OF MERCURY

One of my annoying traits is the tendency to create too many acronyms. In recent years this foible has abated somewhat, but today it surged back, because one occurred to me which I can't resist.

An ORT is an OSS-RSS Trace. It's some locatable aspect of the Real Solar System which (accidentally or not) can remind us of the fictional Old Solar System.

Symbolically it's like a vein of actual situational ore from which the imagination may extract a traditional-style fictional idea, and indeed I could have called it an ORE if I'd chosen an E for Extract instead of a T for Trace. But ORE sounded too ambiguously like physical ore, so I've plumped for ORT, which has the advantage of suggesting the German for "place".

For a general philosophical underpinning see Relations with the real, and for news of discoveries see Science catching up. Here, however, the term ORT is reserved for places, spots where one might stand and think, hmm, this tingles with closeness to a dimensional boundary between fiction and fact...

My first example comes from the planet Mercury, and I don't know why I haven't thought of it before. It's intriguing to reflect, that since that planet has no axial tilt, its north and south poles are just as much "Twilight spots" as the old "Twilight Belt" was supposed to be.

In other words, the actual polar Twilight Spots can be viewed as ghostly reimbursements for the loss of OSS Mercury's Twilight Belt. They are compensatory phenomena, giving us relics of what we used to be able to believe in, and allowing us a couple of OSS-haunted sites in our more humdrum RSS.

Belatedly it has dawned on me that I could have made something of this theme in my novel Valeddom - it would have fit nicely - but there you go: a missed opportunity. I did mention, in the flashback to ancient Mercury, that the polar zones were the sources of life which crept along the terminator as the planet ceased to rotate. But it would have been poignant to go further and reflect that men might still one day visit those twilit poles and, perhaps, feel haunted by a scenario that prevailed only in classic sf.

2023 September 21st:

OCTOPOID ALIENS BECALMED IN THE "SARGASSO OF SPACE"

Reading Edmond Hamilton's Star Trail to Glory I came across a memorable passage in which Captain Future discovers an interstellar craft with its voyagers in suspended animation (a theme Hamilton developed much later in The Weapon From Beyond):

...The eerie occupants of the ship lay in bunklike metal shelves. Above each shelf was suspended a purple lamp, its weird glow falling downward to bathe the grotesque sleeper below. They were huge and scaly, with multiple tentacles - like intelligent and malignant octopi!

"Gods of space, what are they?" gasped Jan Walker.

"Creatures from some other solar system," explained Curt. "Evidently they do not need air." He pointed to the empty tanks along the wall that bore traces of a red liquid. "Their food was synthetic blood..."

And so the cues mount up and we're all set for a sinister awakening of blood-drinking monsters... except (spoiler alert)...

...the octopoids turn out to be friendly! In fact, Captain Future relies on their help in order to escape from the Sargasso. Friendly aliens of alarming appearance are however not unique at this early stage of sf's golden era (the tale is from the Spring 1941 issue of Captain Future magazine) since C S Lewis and "Doc" Smith, to name but two, had already amply explored the theme. Still, this one perhaps shows Hamilton using its rarity to tease the reader somewhat.

Anyhow, the outcome just goes to show that one can never tell...

2023 August 27th:

ROCKLYNNE'S FAR-FUTURE MARS

"Lone Wolf" sent me this comment on Liam Hankins' new page, What makes a good Mars story:

I saw the new Liam Hankins' article on the site about the Mars stories and their types and something came to my mind - he mentions about what he calls "Phase Four" type of story that he hasn't heard of any such which takes place explicitly on Mars, and then I remembered that I've actually read something like that, but couldn't remember what and where... Anyway, the thought bugged me and after a lot of rummaging in my archives and online I finally found it - it's a story by Ross Rocklynne called The Empress of Mars, first published in Fantastic Adventures, May 1939 (https://comicbookplus.com/?dlid=37041). It is set on Mars of the far future - 3000 years after the collapse of the interplanetary civilization, when the remaining descendants of the Earthmen live on the planets as isolated barbaric societies. Apart from that it's more like a Conan-type heroic fantasy, only set on Mars and involving a lot of world-building about the local culture and native life (most of which is provided as footnote quotes from fictional research works) and still leaving some controversies - for instance, it doesn't become clear who build the canals, were there any real native Martians before that, when were written those fictional surveys, if this is a feudal society in the far future, etc.

[Comment from Zendexor:] It sounds as though "Phase Four" Mars should be split into two sub-categories: 4a, with "Martians" descended from Terrans, and 4b, with real, ethnic Martians! 4a would be the COMOLD option whereas 4b would be COMOLD-free.]

2023 July 27th:

SEARCHING FOR FURTHER ADVENTURES ON SASSOOM

This morning I finally got round to something which has been on my "to-do" list for a while: search online for possible sequels to Burroughs' last story, Skeleton Men of Jupiter.

Apart from a reference to one comic, Lost on Jupiter, which isn't what I want, all I found were references to people saying what a pity it is that ERB didn't continue with his Jovian saga.

I find it hard to believe, however, that during the years since 1943 nobody has written a continuation of the unfinished story. Would any readers care to comment?

Well do I remember the last sentence of Skeleton Men: "Soon my Dejah Thoris would be again in my arms." That's a heavy hint, is it not, that when John Carter alights from his sky-craft he will nevertheless find that she's not there waiting for him after all: something will have happened, as it usually does, to place the Incomparable further out of reach for a while. And personally I also read into the last paragraph or so a hint that Carter's own reception is not going to be what he expects: he may well be detained, imprisoned, threatened for some reason in a manner he didn't expect, as he was among the people of Horz in the first part of Llana of Gathol. So there you have two clues.

Next one could focus the Implicizer onto the whole business of working out what happens next...

Incidentally, while searching online as mentioned above, I came across a chronology of events in ERB's fiction. It contains references to many works written by other people as additions to the oeuvre, including various rather ridiculous attempts to mix the personnel (Tarzan going to Venus and meeting Carson Napier, for instance). But no solid-looking continuation (yet) of Skeleton Men.

2023 July 12th:

THE MINIMUM NOD OF RESPECT FOR SCIENCE

The Minnorfsci is nicely exemplified by the specimen given here.

To start with, our invaluable researcher/contributor "Lone Wolf" sent me an extract from a tale by Nelson S Bond set on the tiny asteroid Eros and endowing it with a lush landscape. (I used the extract in Guess The World.) Lone Wolf remarked:

It is mentioned... that Eros has neutronium core to explain its Earth-like gravity, that permits existence of atmosphere and life.

not so lush

not so lushYou see the permissibility, the feasibility, of the part-scientific attitude? Like one who appeases a god by shedding a libation in the form of a perfunctory drop, this excuse of the neutronium core nods at science just respectfully enough to explain the surface gravity of the tiny asteroid, but without the need to give more - that's to say, without feeling any obligation to admit that such a heavy asteroid, due to its drastic gravitic influences on the orbits of the inner planets, would be incompatible with the basic physical reality of our solar system as we know it.

Because this kind of story in terms of physics sits somewhere between fantasy and hard science fiction, some critics would shrug and classify it as "science-fantasy" in such a way as to shunt it into a different category from "science-fiction" proper.

I tend to disagree. I prefer to class it firmly as swimming in the great sf ocean of ideas and themes.

It's a literary realm to which one can gain admission by a sort of tokenism - by nodding at some law in such a way as to gain the right to ignore others!

Surprising, eh? But it works.

Perhaps it works because the nod at Science - the libation to realism - gives you a cut-price ticket to plausibility based on your respect, not for all laws, but for the essential minimum, a sort of artistic hegemony of physical boundaries [see topological excusology]. Having given that nod, you are let in. Thus (now here's a paradox) the minnorfsci is a kind of entrance-spell...

2023 July 4th:

TRAVEL AND ITS EFFECT ON MARTIAN CIVILIZATION

IN BRACKETT AND BURROUGHS

Now that's a good title for a Ph.D. thesis. Here, though, just a few lines on the subject, following on from the previous Diary entry.

I simply wish to point out a contrast, or rather a reversal, which I've never so explicitly noticed before:

In the Brackett Mars tales, travel by advanced means (i.e. spaceships) is plentiful to and from the planet, but once you're there your mobility is quite primitive: you can only ride slowly from point A to point B on the surface of the planet. The situation on Burroughs' Barsoom is the opposite. Space travel in the normal sense of the word hardly exists (Swords of Mars is a partial exception) but, on the other hand, for those who live on it, fast travel around the planet itself is plentifully available, by means of the wonderful Barsoomian flyers and aerial navies.

The Ph.D. thesis - which I'll leave for one of you to write - should explore this contrast's literary consequences.

Talking of travel, I shall be away from home for a few days from tomorrow. (I'll be back the following Monday, the 10th.) I'm going with my spouse to a 50th-anniversary matriculation dinner at Churchill College, Cambridge, where I read History from 1973 to 1976. Little did I know then about websites...

2023 July 3rd:

BRACKETT, BRADBURY AND "PAST-FUTURE" DATES

To start with, here are some comments from the contributor "Lone Wolf" on questions which arose from the page on the Chronology of Captain Future:

Since you mentioned the universe of Leigh Brackett in the foreword on the page and that a similar research might be done on it too, I'll say that this has already been done, more or less. There is this quite informative article in Wikipedia about the Solar System of Leigh Brackett, which I used once to find the titles of the stories to read, related to particular planets: https://en-academic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/1845110# (there are also links to the separate articles for every planet). The chronology is discussed in the end - it seems some of the stories here are also set in the late XX - early XXI centuries (for instance the date of establishing of the trade city of Kahora on Mars is derived indirectly from these stories as being as early as 1981!). There is also this author - Blue Tyson, who does a detailed investigation of Leigh Brackett's "future history": https://www.smashwords.com/extreader/read/14784/1/leigh-bracketts-future-history-connecting-the-stories-an-exa.

I get a peculiar feeling of nostalgia when I read these stories, which are supposed to happen in a future that is now already past, but their Zeitgeist belongs to that era, when they were written, or even earlier. At that time they were considered as a fictional projection into the future, while now we perceive them as a kind of alternative history. And the same with The Martian Chronicles of Bradbury - I've read that in their latest edition the dates given in the book were changed to 31 years later, so that everything begins not in 1999, but in 2030. But somehow this doesn't seem right to me - I'd rather change it to 31 years earlier, as if the first interplanetary flights have begun somewhere in the 1960s, and all the characters and events would seem more proper to that era, if not even earlier. And I actually came across an earlier version of the story The Long Years, published separately in some magazine in the 1940s (I think it was "Planet Stories", but unfortunately I don't remember the details), where the events were actually set somewhere in the 1990s and not in 2026, as in the book, so maybe my idea is not so crazy...

Comment from Zendexor:

I heartily concur with the view that "past-future" dates should be left inviolate in sf texts. Nothing whatsoever is to be gained, and a good deal is to be lost, by tampering with them.

While on the subject of Leigh Brackett it's tempting for me to add that though she's one of my old favourites, I don't read her much nowadays because for me there's something especially frustrating about her work, splendid though some of the tales are when considered in isolation. Somehow, for me the reader, there's a sense of being led on towards a blank barrier - but I can't explain why. After all, consistency and depth are not just the author's business but also rely on co-operation from the reader. Why then do I not feel like co-operating (or gap-filling) as much with Brackett as with Burroughs? Could it be something to do with the fact that interplanetary travel is a given in her stories but not (or hardly at all) in his, and that his therefore derive strength from the concentration of world-building in isolation? I don't know yet; I haven't worked it out.

2023 July 1st:

LIFE BEGINS AT 69 (FOR ZENDEXOR ANYWAY)

Sometimes my wife Mary comes up with a really good idea, of which a noteworthy example is her recent suggestion that I retire from tutoring. Financially this is possible because she will receive her state pension soon - from September onwards - and with hers added to mine we can get by. Yippeee! Not that I don't like my pupils; they've been a great bunch, and a thought-provoking corrective to horror stories of repulsive Yoof. But since I'll turn 70 next January and lack the dynamism of yore, I feel entitled to a rest.

This will, I hope, mean that I can devote more attention to this website and to my ongoing online epic, Uranian Throne. Already, ideas are fizzing in my head at an increased rate. And it's just as well that the planet Ooranye should get more careful attention, since the more the story grows the greater the need to guard against the inconsistencies which naturally tend to creep in to such a sprawling opus.

2023 June 20th:

A MERCURIAN CUSS-WORD, AND OTHER MATTERS

Some notes sent me by Lone Wolf along with his contribution of Guess The World entry 277:

...A funny short story, set as reportages from Mercury, and I wish there was more of it. The authors did quite a world-building for just one short story, but if they ever wrote more of this like a series (for instance, continuing it on other planets), I don't know... There is also mention of a tenth planet in the Solar system, called Hermes, discovered from the observatory on the night-side of Mercury. And here are some examples of the native Mercurian speech:

"Bonskosk, Chief: Which in the local patois means Good morning, Hello, Howdy, Cheerio, Have-a-Drink, How's-your-liver... Take your pick, Chief. The natives have only two hundred basic terms – grunts would be more descriptive – to take care of all their lingual needs."

"...Ransmurl! Which is a Mercurian cuss-word, that covers all cuss-words in the Milky Way galaxy and ten others…"

[The more alien cuss-words we learn, the better; if they were to catch on here, they'd provide relief from dreary Terran expletives.]

2023 June 13th:

HOPING AGAINST HOPE

Swirling around in the depths of my mind, a vast number of classif sf tales undergo intermittent bondings with one another, associations which surprise me, such as the following which I will introduce to you in the form of a riddle. It's a riddle which none of you could guess - I would safely bet any money on that.

Here it is:

What created my recent mental bond between Isaac Asimov’s The Dead Past and Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Swords of Mars?

The Dead Past (Astounding Science Fiction, April 1956) is one of Asimov’s best stories. A scientist learns to dread the use of the Chronoscope, a device to view the past. He realizes that his wife would not be able to stop herself from obsessively watching the end of the life of their little girl who died in a fire; repeat viewings, in the insane hope that somehow the child's fate would turn out differently, would be impossible to resist, bringing psychological disaster. The moral of the tale: not all great technological advances are a good thing (which is an interesting message to come from the progressive Dr Asimov).

How can Swords of Mars bear comparison with that sombre message? Because, equally insanely, I keep re-reading it in the hope that the book’s great disappointment will somehow cease.

The let-down comes after a great promise. I always thrill to what looks to be a great adventure for John Carter and his companions as they approach Phobos, which is subject to a unique physical law whereby all inhabitants and visitors shrink proportionately in such a way as effectively to increase that tiny satellite to the dimensions of a planet. A whole world, waiting to be discovered! Yippee! But then, almost immediately, the protagonists get captured, their movements restricted, and I'm allowed hardly anything of the big scene. Again and again, every few years, I pick up the book and enjoy its prospects only to groan inwardly as I approach the castle of Ul Vas… which doesn’t stop me from the next re-reading…

Cue the narrator’s plea in the Asimov tale: “Let the dead past go!”

2023 June 5th:

HEINLEIN IN SUPPORT OF OSS VENUS

Having provided the answer to the latest Guess The World scene - see Wielding a machete on an insect on Venus - the reader who contributed the excerpt, Lone Wolf, has informed me regarding the story (Tenderfoot in Space by Robert A Heinlein, Boy' Life, May-July 1958):

...it was published in three parts in this boy scout magazine (the excerpt is from part 3 from July 1958). It seems that it was written a year earlier and then republished only after the death of the author [Heinlein died in 1988]. I am not sure to which of his versions of Old Venus it is related (he seems to have created several), it could be that from Space Cadet, but in an earlier age, since some amphibian creatures called "kteela" are mentioned here, although in this story it is not sure whether they are intelligent and there is no contact with them yet.

It's interesting what says Heinlein himself in a short introduction, added to the manuscript he sent to the library (according to the information here ):

" This was written a year before Sputnik and is laid on the Venus earthbound astronomers inferred before space probes. Two hours of rewriting—a word here, a word there—could change it to a planet around some other star. But to. what purpose? Would The Tempest be improved if Bohemia had a sea coast? If I ever publish that collection of Boy Scout stories, this story will appear unchanged."

Comment by Zendexor: This sensible attitude is worth a round of applause!

2023 May 29th:

BANK HOLIDAY THOUGHTS

A pleasant, sunny Bank Holiday Monday - what used to be the Whitsun Bank Holiday and coincidentally this year is actually the day following Pentecost - today was full of warm sunshine where I live (Heysham, Lancashire, England, Earth) and I sat out some of the time re-reading some of David Fromkin's In the Time of the Americans, a sort of multiple-biography centred around those decision-makers who moulded America's foreign policy and directed America's rise to world power in the years 1900-1960. It's a great read.

It got me thinking, wouldn't it be great if a book of the same structure could be written about the great American SF writers of the Golden Age, say 1920s to 1960s. It really cries out to be written: a big fat book interweaving the biographies insofar as they can be interwoven (and much could be done in that line; a lot of the writers knew each other) and taking all available opportunities to link the various life-stories to the history of the time.

It could be a wonderful book. The explosive efflorescence of the sf imagination in those years bears comparison, in my view, with the sudden leap in human thought in the sixth century BC (the Ionian philosophers and the Buddha, and possibly Zoroaster)... but as a culture we're too close to the phenomenon to appreciate it in perspective. Indeed a book which tried to deal with the whole thing might try to generalize so much as to seem dull; but one which concentrated on the USA and on the anecdotal / biographical approach could be a riveting read.

2023 May 15th:

THE GOOD GUESSES OF YORE

I'd like to share with readers a recent email I received from Guess The World's contributor, Lone Wolf.

It concerns the way some pre-Space-Age writers have scored hits or near-hits in their descriptions of other worlds. Lone Wolf writes:

I remember reading somewhere in the OSS Diary on the site about C.S. Lewis describing a blue sunrise on Mars (I hadn't noticed this when I read the book in the early 90s, when there still weren't pictures from the space probes available to view) [note: this was in Eastern Europe]. Recently I was rereading O.A. Kline's Martian novels and found something similar, although quite short and without any details. In "The Swordsman of Mars" there is such a passage:

"Presently the sun, heralded only by a brief dawn-light in this tenuous atmosphere, popped above the horizon, its blue-white shafts instantly dissipating the cold, and swiftly melting the shell of ice which covered the canal. "

It's probably just a fluke, but still curious.

Then, while reading A.K. Barnes' story "Trouble on Titan" (from "The Interplanetary Huntress" series), I stumbled upon another curious piece:

"Saturn loomed gigantic in the sky. Its eternal rainbow rings looked so near, it seemed almost as if one could reach out and break off a piece."

No more details again, but I don't remember any other author mentioning the "rainbow rings" of Saturn before the pictures taken by Voyager 2.

Perhaps there can be made a whole collection of such right or almost

right guesses from the old SF, together with that of Lewis and also Carl

Selwyn's description of the moons of Pluto, which I sent you some time ago. ["The three

moons of Pluto hung low in the east and the enormous Great Moon, the nearby

satellite of the planet, arose beside their departing light, a darker green." From Exiles of the Three Red Moons (see What to see on Pluto).]

It remains for me to confess that I am ignorant of the two Martian novels of Otis Adelbert Kline, though I hope to repair this lack some day. I have read some of his Maza of the Moon, but so far have not been motivated to finish it - though perhaps this was due to being in the wrong sort of mood...

2023 May 2nd:

LOPER CIVILIZATIONS

...Yes, they could find things. Civilizations, perhaps. Civilizations that would make the civilization of Man seem puny by comparison. Beauty and, more important, an understanding of that beauty. And a comradeship no one had ever known before...

On re-reading the above passage in Desertion - Clifford Simak's immortal ten-page classic - I got to focusing more sharply than before on the possibilities of a civilization created in the vastness of Jupiter by the long-lived and multi-sensory Lopers.

Such a civilization wouldn't be characterized by physical cities; on the tale's version of Jupiter, the construction materials and techniques for building would not be available. Nor would they be needed. Lopers are so strong, they can live in the open, the giant planet's howling maelstroms being mere gentle breezes to them.

Nevertheless these creatures' bodies and minds are so equipped, that they could create realms and empires of awareness. Here's how I imagine it might work: if for example a Loper notices some new relation or aspect of his environment, he can share that connection with his fellows, who in turn might build on it with further bolt-on bits of awareness, till a new "city" of appreciation arises, as firm and solid in the mind as London weighs on the banks of the Thames.

Then again - who knows - maybe I'm wrong to dismiss the chance of material buildings: in addition to the edifices of mind, mind-over-matter might also enable the construction of new types of physical cities too, types which can withstand the worst that the Jovian weather can hurl.

No doubt about it, Desertion is an open-ended tale par excellence.

2023 May 1st:

THE WEAVING FLOW OF ERB'S PROSE

More thoughts from my re-reading of The Master Mind of Mars:

I took the trouble to note an unexceptional paragraph which seems to embody the unobtrusive enchantment of the author's style. It's not quite a "conversational" style - though, more often than not, it goes with first-person narration. Rather than "conversational", I would pick a term like "loose, flexible and relaxed", with the proviso that it's not at all rambling or diffuse; and it can vary its direction like a yachtsman is able to tack to and fro while keeping his aim in view.

Here is the paragraph - it's from page 38 of my edition of the book, and is from the chapter entitled "The Compact":

But I was presently to learn that he had an excellent reason for what he was doing - Ras Thavas always had an excellent reason for whatever he did. One night after we had finished our evening meal he sat looking at me intently as he so often did, as though he would read my mind, which, by the way, he was totally unable to do, much to his surprise and chagrin; for unless a Martian is constantly upon the alert any other Martian can read clearly his every thought; but Ras Thavas was unable to read mine. He said that it was due to the fact that I was not a Barsoomian. Yet I could often read the minds of his assistants, when they were off their guard, though never had I read aught of Ras Thavas' thoughts, nor, I am sure, had any other read them. He kept his brain sealed like one of his own blood jars, nor was he ever for a moment found with his barriers down.

Now to mark each of the four supple inflection points [SIPs] - the tacking-style changes of direction - in this piece of prose:

But I was presently to learn that he had an excellent reason for what he was doing - Ras Thavas always had an excellent reason for whatever he did. One night after we had finished our evening meal he sat looking at me intently as he so often did, as though he would read my mind, [SIP] which, by the way, he was totally unable to do, much to his surprise and chagrin; for unless a Martian is constantly upon the alert any other Martian can read clearly his every thought; [SIP] but Ras Thavas was unable to read mine. He said that it was due to the fact that I was not a Barsoomian. [SIP] Yet I could often read the minds of his assistants, when they were off their guard, [SIP] though never had I read aught of Ras Thavas' thoughts, nor, I am sure, had any other read them. He kept his brain sealed like one of his own blood jars, nor was he ever for a moment found with his barriers down.

The "But" at the start of the paragraph could also count as a SIP, relative to the narrator's preceding thoughts, so, really, the total is five SIPs, five loose-jointed inflections, accumulating the narrative's easy lope.

I wish my own prose was as hammock-swayingly relaxed as this. I'm unfortunately too law-abiding, for example, to start a paragraph with "But".

2023 April 30th:

THE SNAG TO BRAIN-TRANSPLANTS FOR MARTIAN RULERS

In general my trouble with re-reading the Barsoom books is that I know them so well, I can hardly read them anew... but a few days ago I did, after all, find within me a yen to re-read The Master Mind of Mars. It appears I chose the right moment. The ever-rolling stream of Time had finally reached the stage where I was ready to be refreshed by volume 6 of the Barsoomian saga. Indeed some details I had forgotten... a sign it was about time for a re-charge.

However, something else also happened. It occurred to me for the first time, the risk Xaxa was taking in getting Ras Thavas to give her old brain a new body. For a despotic ruler to undergo a radical change of outward appearance, in a culture which is based on the personal recognition of that ruler, is more or less to invite rebellion.

I mean to say, just consider the issues if England's Henry the Eighth had had the services of Ras Thavas. Henry in his mid-fifties, going to pieces physically, might well have yearned for a younger body - but would he have dared to go for the option? I very much doubt it. Perhaps if the operation had been carried out in a blaze of publicity, with observers ready to attest that the King's brain was the one placed in the young body, he might have tried it. On the other hand plenty of people might have had motives to cast doubt on the proceedings. Look what happened at the birth of the son of James the Second. People didn't want to believe the baby was his, or that there was a baby at all; so they invented the "warming pan plot".

Now then - am I criticising Burroughs and accusing him of implausibility? Perish the thought. I am not accusing but praising him for his implausibility; admiring him for the way he bamboozled me for so long. One test of a great writer is how far he can suspend not only our disbelief but our critical faculties.

Besides, you could say it just goes to show how old Xaxa's nasty personality shone through. Even when she was no longer ugly to look at, her courtiers had no doubt it was she.

So, come to think of it, ERB can be awarded his certificate of (psychological) plausibility after all.

2023 April 28th:

A WORD PUT RIGHT

Recently re-reading an old favourite, Clark Ashton Smith's The Door to Saturn (due to be discussed in Sunday's up-coming podcast), I came across the jarring use of "hardly" in the final paragraph: