- Home

- >>

Venus

[+ links to: A Life of Leisure and Renewed Vigor - Amtor - Gloomstalker - An Ice-Age Venus? - An Ice-Age Venus II - The Kuttner-Moore Venus - Love the Amtor Article - Perelandra - Project Utopia - Sentinels from Space - The Sky People - Slaves of Venus - Venus Quiz - What to see on Venus ]

Let's begin with the marvellous old painting by Lucien Rudaux, of the view from a spaceship descending through the cloud-layers of Venus: what might those clouds hide?

The jungle Venus, the ocean Venus, the desert Venus - any of these versions might lurk below. Amazingly, whichever of them it turns out to be, it will somehow fit our idea of the planet!

Talk about being flexible!!!

A sort of OSS butler must bustle up in our minds, handing us the cloak "Venus" to wrap around the next tale, no matter how inconsistent the setting may be with the one before. And this wrap is all-embracing....

the apparently impossible wrap

That's to say, the over-arching concept "Venus" somehow goes with every setting that's imagined to exist underneath that veil of clouds.

Stid: Until the veil is pierced by our radar. And then the versions are narrowed down to one. The desert Venus, as in this Mel Hunter painting. Hot, dry, uninhabitable.

Harlei: Which is why the Old Solar System is more fun than the New.

Zendexor: Yet sterility may still leave room for beauty, as the Hunter picture suggests. But let's leave that to one side and get back to the butler with the cloak, for I sense that we are skimming close to a theme that's worth investigation.

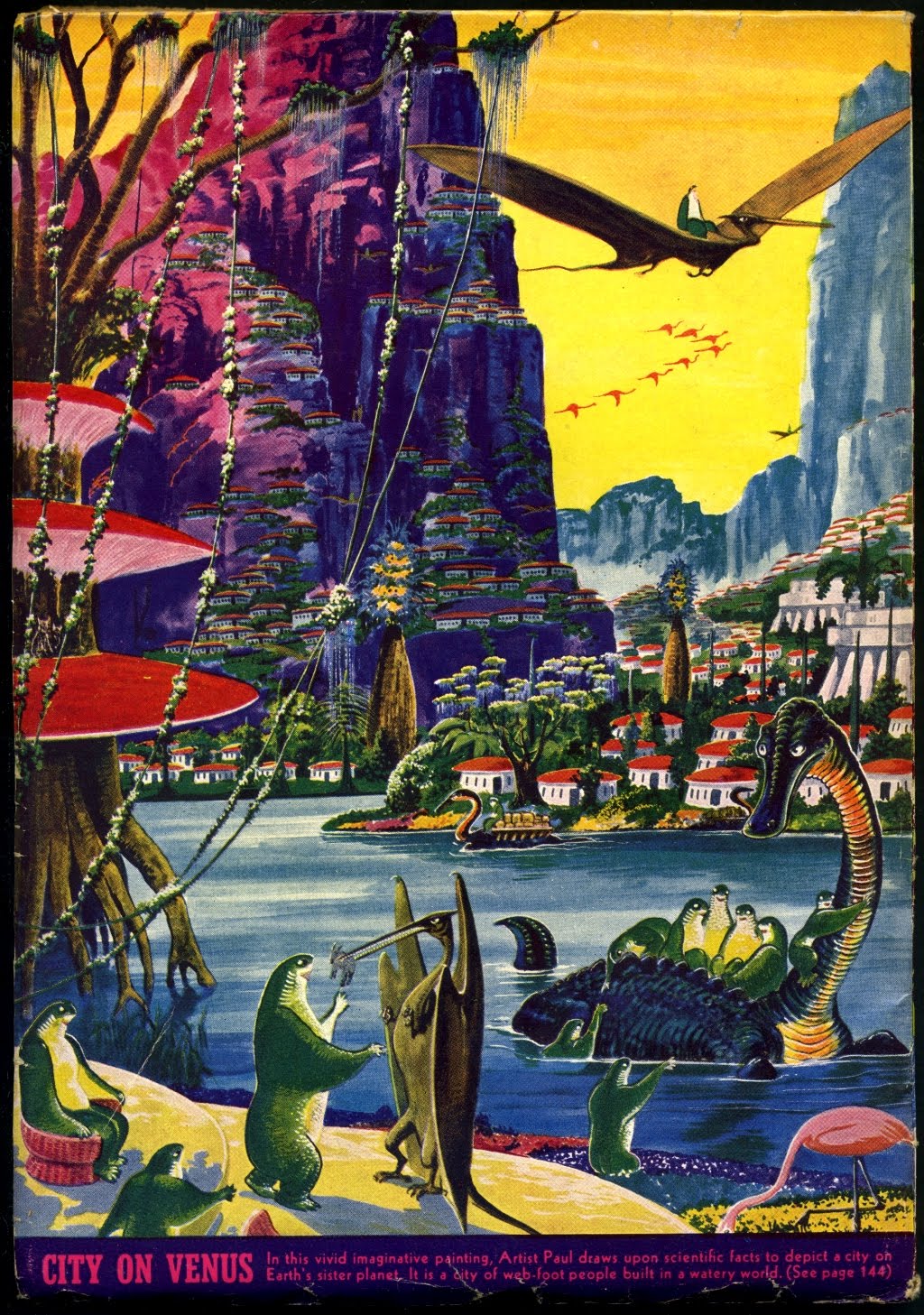

by Frank R Paul

by Frank R PaulImagine you're the editor of Planet Stories, or some such magazine devoted to Solar System adventures.

You wade through a heap of typescripts of tales set on Venus. Imagine you're in luck and you find your pile this month contains Enchantress of Venus, Men of the Morning Star, Parasite Planet, Logic of Empire, Clash By Night, Before Eden, The Long Rain, A Voyage to Sfanamoë and The Immeasurable Horror.

Well, what happens? You go mad and decide to publish them all in a special Venus edition - subsidized so that your readers can afford it -

Stid: Which no doubt means you must be an eccentric millionaire, but given the backing, the idea should work - they're all good stories. So what's your point? What are we supposed to be impressed about? The sheer variety of these yarns? Surely that's to be expected. Every planet in the solar system has been fictionally conceived in myriad different ways. Are you making Venus out to be a special case?

Zendexor: In a way, yes. It stems from the cloud-cover. Though it's the nearest planet, Venus was also the most hidden, right until the 1960s. Absolutely hidden by that bland, heavy atmosphere. So of course, writers could portray the surface how they liked. That's what you'd expect, given this opportunity - the advantage naturally taken, to put one's own interpretation on the mystery. But then, following on from that, you'd expect something else.

You'd expect any overarching idea of "Venus" to sag apart under these conflicting strains. You'd expect it to break up and dissolve under the contrary forces of incompatibly different ideas. Yet, that simply doesn't happen. Immediately the reader picks up whatever tale, it's not "Ah, so this is Venus, the other one must have been something different"; instead, it's "Ah yes, this is Venus again. Another version - but still Venus."

Stid: You're making a psychological point about the way the reading experience works, but I'm not sure I agree with you. I'm not sure we need to be all that surprised - because I doubt your basic premise, namely, the supposedly incompatible variety of the stories. To me they seem to overlap quite a bit. Take that list of tales you gave: all of them (except Before Eden and possibly Men of the Morning Star) belong to the sub-sub-genre of "swampy/jungly/fecund-Venus" tales...

coincidences between writers

And talking of overlap, let me call a witness. Our friend Harlei. Here, Harl, answer me this. Have you noticed a striking fact in common between Burroughs' Pirates of Venus and van Vogt's The World of Null-A? And, to a lesser extent, Russell's Sentinels from Space?

Harlei: Yes, as a matter of fact. Trees. Enormous trees, thousands of feet high in ERB's account, maybe as big in Van Vogt's, and in the Russell book one also meets a big forest.

Also, names with "Thor" in them. Thorstern the villain in Sentinels, and Thorson ("the implacable Thorson") in The World of Null-A. An odd though trivial coincidence. Other ideas which seem to have taken root in more than one writer, are those of castles on Venus, and Venusian shape-deceivers.

Stid: You see, Zendexor, it's no use your exaggerating the differences, the incompatibilities, and then making a big mystery of how a common theme can still unite them. Even Harlei's against you on this issue. I reckon that in the minds of sf writers the theme of Venus has formed a mental swamp which, all right, gives life to blooms of all kinds... but which also has currents common to many.

Zendexor: A swamp with currents, eh? Well, we can't all be wizards at metaphor.

Now then: it's my turn to bring in some evidence. I shall cite two stories, two fecund-V stories written by the same author and, to top it all, published back-to-back, as it were, in two successive issues of Weird Tales. And I shall show that despite all those factors pushing them to get grouped together, they're still so wildly different, that it makes sense to be amazed.

one fecundity not like another

A Voyage to Sfanomoë is a charming short (eight pages) about the voyage of two old Atlantean brother-scientists who escape the demise of their doomed continent by building a spaceship and flying it to Venus. It is a gently told, picturesque tale of futility. The Atlanteans disembark after years of travel (their spacecraft must not have been built for speed) and find the planet to be a wonderland of narcotic blooms. The flowers "grew from a ground that their overlapping stems and calyxes had utterly concealed; they hung from the boles and fronds of palm-like trees they had mantled beyond recognition; they thronged the water of still pools; they poised on the jungle-tops like living creatures winged for flight to the perfume-drunken heavens." The arrivals "were delighted, they called out to each other like children, they pointed at each new floral marvel..." and they swiftly become absorbed and overgrown themselves.

The reader is poised above the tale like an astral spectator, appreciating the exquisite doom of the two old men, who after all had shown no compassion themselves to their doomed fellow citizens of Atlantis. It is one of Clark Ashton Smith's most stylish tales, like legible music.

And then we have his other Venusian adventure, The Immeasurable Horror.

This is the definitive fecund-V tale. No more vivid version can be imagined.

Published in the September 1931 issue of Weird Tales, it is narrated by a survivor of the Venus expedition of 1979. "The most exuberant tropical jungle on Earth would have been a corn-patch in comparison. The sheer fertility of it was stupendous... everything was overgrown, overcrowded, with a fulsome rankness that pushed and swelled and mounted even as you watched it. Life was everywhere, seething, bursting, pullulating, rotting."

There's nothing in literature quite like the planetary coaster's battle to escape a protoplasmic monster many miles in length which is eating its way through the jungle, absorbing everything in its path.

The theme overlaps somewhat with that of the other story, but the atmosphere, the tone is quite different. They are two different worlds, despite being written by the same man and near enough at the same time. Two visions, which could hardly co-exist. And yet, it's always Venus; it always comes back to that.

We readers must have an instant orientor somewhere in our minds.

Harlei: But of course a writer can't trust too far in the "orientor". I mean, if you were to write a story about the planet without its cloud layer, it wouldn't work.

venus and the future of man

Zendexor: Unless you gave a reason. As in the story History Lesson, which has as its theme the first Venusian expedition to Earth, in a future age when changes on the Sun bring ice and extinction to our world, and clear the clouds from Venus.

As you might call it: the future of the Old Solar System.

Harlei: And talking of our future, according to the ultimate future history Last and First Men, Venus is it! It becomes our world, our only world, for a period lasting six hundred million years.

Zendexor: And it's a bit cramped, because it doesn't have much land area, either before or after the somewhat genocidal terraforming which the Fifth Men undertake as they seek to escape from doomed Earth. The swordfish-shaped Venerians are wonderfully described in about three pages before being wiped out. (For more on Stapledon's Venerians see our page on radioactive life.)

Note also that the oceans of Venus are the future home of humanity for some centuries during the saga which I name the Saga of Re-Emergence, discussed on the Kuttner-Moore page.

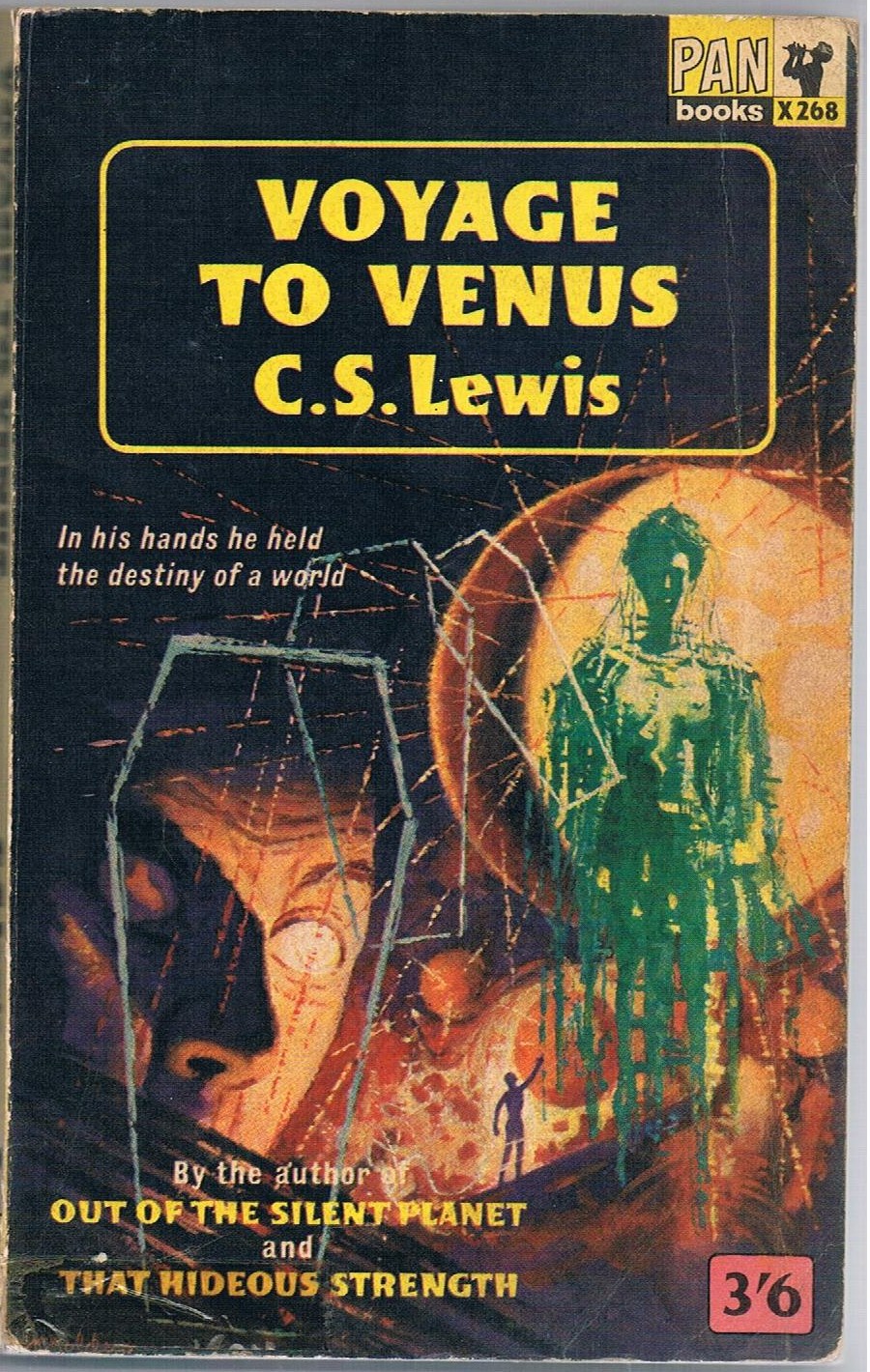

But for the best watery Venus - in fact by far the best of all visions of our sister planet - let's turn at last to Perelandra, the version of Venus we'd all most like to live on. (Except for one critic I once read, who called it a "candyfloss paradise" and seemed to think that we'd get bored there. Poor chap, he probably would.)

Perelandra is famous as a unique theological thriller - a kind of re-run of the Temptation of Eve - and this dramatic aspect of the story is brilliantly handled. But that overworked word "brilliant" also needs to be used again and again with each of the novel's other aspects. The numinous physical reality of this ocean-Venus, with its floating islands and its two majestic Fixed Lands, is unforgettable, the narration of its discovery unputdownable. And no matter how central the story to human fates, the author is careful to show, by giving us mysterious glimpses of aquatic and subterranean intelligences, that the world of Perelandra belongs to other races too. We are left with a sense of having brushed against something huge, with every fate central in its own way.

Click for more on Perelandra.

Leigh Brackett, "Enchantress of Venus" (1949); Ray Bradbury, "The Long Rain" in The Illustrated Man (1951); Edgar Rice Burroughs, Pirates of Venus (1934) and the other volumes in the Amtor series; Arthur C Clarke, "Before Eden" in Tales of Ten Worlds (1962) and "History Lesson" (1949); Edmond Hamilton, "Men of the Morning Star" (Imaginative Tales, March 1958); Robert A Heinlein, "Logic of Empire" (Astounding Science Fiction, March 1941); Henry Kuttner and C L Moore, "Clash By Night" (1944) with its sequel Fury (1950); C S Lewis, Perelandra (1944) - later published in paperback as Voyage to Venus; Larry Niven, "Becalmed in Hell" (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, May 1965); Eric Frank Russell, Sentinels from Space (1952); Clark Ashton Smith, "A Voyage to Sfanomoë" (Weird Tales, August 1931) and "The Immeasurable Horror" (Weird Tales, September 1931); Olaf Stapledon, Last And First Men (1930); S M Stirling, The Sky People (2006); A E Van Vogt, The World of Null-A (1948); Stanley Weinbaum, "Parasite Planet" (1935)

Click for more on the characters-of-worlds debate.

For the Venus of Edgar Rice Burroughs, see the page on Amtor.

For a good take on the hot-and-arid Venus, see the story Becalmed in Hell, briefly mentioned in the page on hyper-brains.

For some of Weinbaum's Venusian life see the page on intelligent plants.

For a detailed neo-OSS Venus by a twenty-first-century author, see The Sky People by S M Stirling.

For Heinlein's Logic of Empire and Tobias Buckell's Pale Blue Memories see Dylan Jeninga's Travelogue page, Slaves of Venus.

For a different view of the diameter of Venus, see the extract from van Vogt's The Great Engine in Venus Quiz.

See the OSS Diary, 14th November 2016, for the theory of Franz von Gruithuisen (1774-1852) that the "ashen light" might come from festivities on the accession of a Venusian emperor.

See the OSS Diary, 16th November 2016, for the fecund Venus of Wyndham's The Outward Urge.

See Venusian Squid Captured on Film for van Vogt's Film Library.

For Venus the so-called "useless planet", and what might be done about it by reality-change in the far future, see the OSS Diary for 15th March 2017.

For The Immeasurable Horror by Clark Ashton Smith, see the OSS Diary, 9th April 2017, and the podcast by the Roll Off A Tangent team.

For Hot Trip for Venus by Randall Garrett see the Diary, Backbone of the Old Solar System.

See Pot Luck on Venus for a nice summary of the uncertainty facing the first explorers, in Alan E Nourse's The Native Soil.

For the Northwest Smith adventure Black Thirst, see Evergreen Promises.

For the wildlife of the Venus of Arthur K Barnes, see Interplanetary Huntress.

See the Philip K Dick page for the crash-landing on Venus by the adapted men in The World Jones Made.

For the Nebula-Award-winning Venusian "fishing story" The Doors of his Face, the Lamps of his Mouth see The Zelazny Venus.

See the participatory fun illustrated in Venusian ride at the 1939 World's Fair.

Franz von Paula Gruithuisen's theories on the Ashen Light are discussed in the Diary entry, Celebrating Venusian emperors' coronations.

For the resurfacing of Venus about 700 million years ago see: The theme-filching habit - ancient Venus.

The contradiction in Christopher Priest's The Perihelion Man of Venusians existing on an arid uninhabitable modern version of Venus is discussed in Wrench the plot.

Test your expertise regarding the Mystery Planet with our Venus Quiz.