eras, periods and epochs:

the ages of earth

tales that touch upon deep time

whimsical introduction

The ages of the Earth, and the marvellous names given to them, so fascinated me as a child, that I learned those names early and even wrote a story in which they figured as living beings. These incorporeal creatures, "Periodics" as I called them, were full of their own personalities which were somehow inherent in the names; though as for the events in the story, I no longer have the faintest idea.

It's likely that my knowledge of the names and of the main outlines of Earth's story were derived from Patrick Moore's True Book About the Earth (1956), which I borrowed from the town library (though many decades later I obtained my own copy).

Almost two-thirds of a century later, all that old fascination has been transmogrified into the sort of interest you'll see pursued below: namely, what science-fictional imaginings have to show us in connection with those ages.

Before we get down to it, here's one whimsical regret:

Any retrospective names for eras are lacking in what might be termed "local empathy". That's to say, because the inhabitants of the eras didn't know the names we've given to their times, they could not - even if they had been thinking beings - share with us the name-awareness which we have for those times. It's the same sort of problem that exists for dates BC. For example think with regard to classical Athens, the resonant years 480 BC and 431 BC are thus numbered very meaningfully for us, but not at all for them. Contrast the way in which, when we think back in our own history to (for example) 1914, we know we're using the same year-number as those who lived then. "1914" resonates, therefore, with historian and participant, equally. Not so with the big dates of the Athenians; and indeed the ancients seem not to have cared about year-numbers much.

Anyhow, let's forge ahead with what we've got. Who knows, perhaps one day the past will be in some sense colonized with some mind-sharing process which we can't guess at as yet, enabling "local empathy" to break out all along the time-line!

precambrian time

Another name for this super-eon (comprising the Hadean, Archaean and Proterozoic eons) is the Cryptozoic which is the term Brian Aldiss uses in the novel of that name (1967).

hadean eon

...The Earth... was in a semi-molten state. The temperature beyond their protective sphere and beyond the entropy wall was several thousand degrees Centigrade. It seemed to be the hour of dawn, but there had surely been no proper night... All about them was a sea of ash, patched with streaks of broken light which radiated upwards. The sea heaved; the ash was but a thin crust, covering an unending gleet of molten rock... [Cryptozoic! (1967)]

archaean eon

This is when rain first fell.

...They were standing on the generalized floor with which mind-travel had made them familiar. The ground was some ten feet below their heels, so that they appeared to be suspended in mid-air. It was a long while before any of them could bring themselves to step forward.

The world sweated and shivered below them, waking into the long fever of being. Great belts of rain were moving across the face of the planet, more like rivers that flowed vertically than ordinary rainstorms. The rain was the color of thin varnish.

"The Cryptozoic - but we picked a showery day!" Silverstone said, grinning uneasily.

The wilderness of rock below them fermented liquid. Everywhere, its black and tremendous teeth were lashed by a frenzy of water seeking a place to run to...

Yellow water gargled into brown amid black basalts. In the sky, the same dun flags waved as the cloud-dance passed perpetually overhead. Of the sun, no sign existed. There was only a series of lighter or darker patches where the suspended moisture fell or failed to fall.

The mind-travellers could not tell whether they hung above land or above the makings of a sea bed... [Cryptozoic! (1967]

In this eon we first encounter the use of a remote time-period as an escape-proof prison:

illustration by H W McCauley

illustration by H W McCauleyA woman reporter who had been granted the final pre-execution interview with a condemned man, Adam Slade, has been taken hostage by him in his break for liberty.

...Outside the dome there was rock. Rock only, twisted and convoluted and thrusting and gigantic like monoliths of a race of giants. Rock alone under the awesome gray sky. Steaming rock, for some of the terrestrial waters were still trapped at great depths. And the sea far off, booming against rocky headlands, hissing tidally and slowly, in an age-long process, pulverizing the rock. The sea far off, a clean sea, not sea-smelling sea, a sea whose waters must evaporate countless times and be borne up over the naked rocks in vapor and clouds and come down in pelting, endless rain and rush across the rock, frothing and steaming - a sea which must do this countless times in the eons to come, and would do it, to bring salinity to its own waters...

...Marcia Lawrence took a deep breath and asked suddenly, "Are you going to kill me?"

"Hell, I don't know. I got no reason to - unless you make me. We're going back there. We're double-tracking along the beach, get me? Back to the prison dome."

"But - "

"Adam Slade won't starve to death out here. We'll double back to the dome - and the time machine."

"Oh," she said. They began to walk along the edge of the sea, its waters sullen gray, mirroring the sky. Here on this dawn earth the sky has as yet never been blue, for the primordial waters were still falling, falling. It rained almost all the time and the air was thick with moisture and every night when the sun - as yet unseen by the dawn earth except as an invisible source of light - went down and darkness came, the mists rolled in from the sea. In the morning whether rains had fallen or not the ground was soaked and tiny freshets rushed down to the sea, returning to it...

...She became aware of rain when they left the cliff overhang. There was almost no wind and the rain came down slowly at first, huge slow drops which splattered on the black rock...

...Then, all at once, someone opened the sluicegates and the rain bombarded them. It slapped and bounced off the rock like pistol shots. It struck them like hammers...

- from Prison of a Billion Years by C H Thames (Imagination, April 1956)

phanerozoic eon

paleozoic era

cambrian period

The Cambrian as a place of political exile in Robert Silverberg's Hawksbill Station (Galaxy, August 1967) is used as a setting without any attempt to deal with the time-paradoxes involved. Perhaps the author considered it sufficient to send people back such a huge length of time ("a billion years", it's loosely called, whereas actually it's not much more than half that), the idea being that any disturbance created by the exiles would be blanked out in such a long interim; a conclusion which ignores the "butterfly effect" of multiplying change.

Or it could be the "rubber-band effect" elucidated by one of the characters in Poul Anderson's Time Patrol (Fantasy and Science Fiction, May 1955):

"...You see, it's rather as if the continuum were a mesh of tough rubber bands. It isn't easy to distort it; the tendency is always for it to snap back to its, uh, "former" shape..."

This could be it, though Silverberg doesn't bother to say so. For further exploration of the theme see Time Travel and Reality Change - especially with regard to Barrington Bayley's The Fall of Chronopolis.

For more on Hawksbill Station see A glimpse of the prehistoric Moon.

In Perelandra (1944) by C S Lewis, Dr Ransom, about to be transported to Venus, mentions that he will be able to speak the language because it is "Old Solar", the language of the hrossa whom he met on Mars (in the previous volume of the cosmic trilogy, Out of the Silent Planet):

"But what about the other two languages on Mars?"

"I admit I don't understand about them. One thing I do know, and I

believe I could prove it on purely philological grounds. They are

incomparably less ancient than Hressa-Hlab, specially Surnibur, the

speech of the Sorns. I believe it could be shown that Surnibur is, by

Malacandrian standards, quite a modern development. I doubt if its birth

can be put further back than a date which would fall within our Cambrian

Period."

ordovician period

Andrew Thornton, geologist narrator of Clifford Simak's The Marathon Photograph (first published in Threads of Time, 1974, ed. Robert Silverberg) has discovered an alien capsule which is promptly claimed by someone he's fairly certain is a time-traveller.

"OK, Charles," I said. "You say you want this thing. As a start, perhaps, you can tell me what it is. And be damn careful what you tell me. For my part, I can tell you that it's embedded in the stone. See how the stone comes up close against it. No hole was ever bored to insert it. The limestone's wrapped around it. Do you have any idea what that means?"

He gulped, but didn't answer.

"I can tell you," I said, "and you won't believe it. This is Platteville limestone. It was formed at the bottom of an Ordovician sea at least four hundred million years ago, which means this thing is an artifact from at least as long ago. It fell into the sea, and when the limestone formed it was embedded in it. Now speak up and tell me what it is..."

silurian period

In Hawksbill Station by Robert Silverberg (Galaxy, August 1967) Jim Barrett, leader of the male exiles who have been banished to the Cambrian Period, mentions that the authorities segregate those who are to be banished into the past by sex, to prevent a viable colony from being established:

"...So they don't send women here. There's a prison camp for women, too, but it's a few hundred million years up the time-line in the late Silurian, and never the twain shall meet..."

[At least that means the women can have fish, of a sort, in their diet.]

The supercomputer in Keith Laumer's The Great Time-Machine Hoax (1964) demonstrates its powers:

"I have found evidence of three visits to earth itself by extraterrestrials in the past..."

"When?"

"The first was in the Silurian Period, just over three hundred million years ago..."

devonian period

Brian Aldiss' Cryptozoic (1967) opens in this period, with the artist-protagonist Edward Bush mooching around in his condition of mind-travel, which allows him and other tourists to visit the far past without being able to affect it in any way.

...The distant sound of motor-bikes, the only sound in the great Devonian silence, made him nervous. At the fringe of his vision, a movement on the ground made him jump. Four lobe fins jostled in a shallow pool, thrashing into the shallows. They struggled over the red mud, their curiously armored heads lifting off the ground as they peered ahead with comic eagerness...

The legged fish snapped at insects crawling on the mud banks or nosed eagerly in rotting vegetation... [p.16-17]

The noise-level of modern society reaches the point at which Travers, the protagonist of Therapy 2000 by Keith Roberts (New Writings in SF-15, ed. John Carnell, 1969), becomes desperate for relief.

...he took to wondering if there had ever been a time - in the Cambrian for instance, or the lazy, lagoon-haunted Devonian - when there had been Quiet...

mesozoic era

triassic period

From The Shadow Out of Time (Astounding Stories, June 1936) by H P Lovecraft:

...For some time I accepted the visions as natural, even though I had never before been an extravagant dreamer. Many of the vague anomalies, I argued, must have come from trivial sources too numerous to track down; while others seemed to reflect a common text book knowledge of the plants and other conditions of the primitive world of a hundred and fifty million years ago—the world of the Permian or Triassic age...

Well, which is it to be? Permian or Triassic? I have plumped for Triassic because for some reason that's how I've always thought of it whenever I'm reminded of this stupendous story with its theme of a mind-switch between a modern professor and a creature of the far past.

Bear in mind also that the end-Permian extinction event was the most cataclysmic in Earth's history. That might make the succeeding period a fit time for intelligence to evolve as a way to cope with crisis, with the result that the cone-shaped beings described by Lovecraft were on hand to suffer the mind-swap inflicted upon them by the ruthless Great Race fleeing their dying planet.

Also, if the Great Race were in the Permian, their main trouble would surely be the coming recorded extinction event, whereas the story tells us that a quite different fate awaited them...

jurassic period

Mind-travellers in Brian Aldiss' Cryptozoic (1967) venture into the Jurassic.

...Not until the afternoon, as they were coming down onto the plains, did they see the first creatures of the plains, sporting in a valley. Instinct asserting itself, Bush's impulse was to watch them from behind a tree. Then he recalled they were less than ghosts to these bulky creatures, and walked out into the open towards them. Ann followed.

Eighteen stegosauri seemed to fill the small valley. The male was a giant, perhaps twenty feet long and round as a barrel, his spiky armor making him appear much larger than he was. The chunky plates along his backbone were a dull slaty green, but much of his body armor was a livid orange. He tore at foliage with his jaws, but perpetually kept his beady eyes alert for danger.

He had two females with him. They were smaller than he, and more lightly armored. One in particular was prettily marked, the plates of her spine being almost the same light yellow as her underbelly.

About the stegosauri frisked their young. Bush and Ann walked among them, absolutely immune. There were fifteen of them, and obviously not many weeks hatched. Unencumbered as yet by more than the lightest vestige of armor, they skipped about their mothers like lambs, often standing on their tall hind legs, sometimes jumping over their parents' wickedly spiked tails...

On the other hand Aldiss' short story Poor Little Warrior! (Fantasy & Science Fiction, April 1958) features an actual physical time-traveller, a rather pitiful big-game nimrod:

Claude Ford knew exactly how it was to hunt a brontosaurus. You crawled heedlessly through the grass beneath the willows, through the little primitive flowers with petals as green and brown as a football field, through the beauty-lotion mud. You peered out at the creature sprawling among the reeds, its body as graceful as a sock full of sand...

[Did Aldiss know that grass isn't supposed to have appeared yet in the Jurassic?]

Extracting oil from this period and shunting it up to our time to solve the energy crisis is the ostensible purpose of the operation in Poul Anderson's Wildcat (Fantasy & Science Fiction, November 1958):

...Automation replaced thousands of workers, so that five hundred men were enough to handle everything, but still the compound was the merest scratch, and the jungle remained a terrifying black wall. Not that the trees were so utterly alien - besides the archaic grotesqueries, like ferns and mosses of gruesome size, there were cycad, redwood and gingko, scattered prototypes of oak and willow and birch. But Herries missed wild flowers.

A working party with its machines was repairing the fence the brontosaur had smashed through yesterday, the well it had wrecked, the viciously persistent inroads of grass and vine...

[So - here's another writer who writes about "grass" in the Jurassic! And later on Anderson's characters meet a tyrannosaurus - which as far as is known didn't exist until the late Cretaceous. If only he'd been satisfied with an allosaurus...]

cretaceous period

The Irish inventor Terence Michael Aloysius Donovan, inventor of time-travel via a coiled structure with gaps of 60 million years, visits the Cretaceous twice in P Schuyler Miller's The Sands of Time (Astounding, April 1937).

...The Triceratops herds paid not the slightest attention to him. He doubted that they could see him unless he came very close, and then they ignored him. They were herbivorous, and anything his size could not be an enemy. Only once, when he practically fell over a tiny, eight-foot calf napping in the tall grass, did one of the old ones emit a snuffling, hissing roar and come trotting towards him with its three sharp spikes lowered and its little eyes red...

Donoval is later rescued by, and in turn rescues, an exterrestrial human woman who seems to be in a paradoxical political position with regard to her followers: treated as a goddess so long as she conforms to an ideal, but otherwise condemned.

Time-traveller Bowden Karvel in Lloyd Biggle Jr.'s The Fury Out of Time (1965) is leading a group of similarly stranded aliens in an apparently fruitless quest for uranium fuel on Cretaceous Earth:

...He turned the column toward a clump of strange-looking trees that stood on the bank of a small stream. They were short and stubby, with armored trunks and palmlike clusters of small leaves on long stems. The shade that they cast was negligible and the stream held a mere trickle of water, but it was the only oasis that the bleak landscape offered.

Karvel got the Hras settled under the trees, and while they rested he refilled his canteen. Then he took the uranium detector and walked a circle with it...

...There was life everywhere. The startlingly strange merged and blended with the unexpectedly familiar. Long-beaked, toothless birds circled above the trees, swarms of insects probed small blossoms in the dry, thick-bladed vegetation that crunched underfoot, and an endless variety of scurrying, lizard-like creatures fled their line of march or watched them warily from a distance.

Twice Karvel glimpsed dinosaurs: a long neck arching briefly beyond a rise of ground; several of an ostrichlike species skipping over a distant hill...

Asa Steele in Clifford Simak's Catface (1978), able to avail himself of "time-roads" created by an alien friend, visits the Cretaceous. Unlike Aldiss when writing about the Jurassic, Simak on the Cretaceous covers himself against charges of unwitting anachronism with regard to grass:

The sun stood straight overhead. The air was warm, but not too warm, and a little breeze was blowing from the west. It reminded me of a day in early June before the summer heat clamped down.

First I had seen the homelike trees, then the cycad. Now I began to notice other things as well. The ground was covered, although not entirely, by dwarf laurel, sassafras and other little shrubs. Grass was growing in scattered patches - rough, tough grass and not too much of it - nothing like the grass of the Pleistocene that tried to cover every square inch of soil. I was surprised at the grass. There shouldn't have been any. According to the textbooks, grass hadn't shown up until much later, several millions of years later. But here it was tho show us how wrong we could be...

That was from p96-7. On p115-6, we have a memorable encounter with more than one tyrannosaurus - from which Asa Steele gets the documentary proof he needs to found his time-travel safari firm. Later, p213-7, we have an expedition to uncover what has happened to a rather tragic safari... All in all, Simak's coverage of the Cretaceous in this novel is pretty effective.

Dinosaurs aplenty appear in Simak's Small Deer (Galaxy, October 1965), in which a tinkerer builds a time machine and explores the Cretaceous out of curiosity. He sights a tyrannosaurus:

....His tail rode low and awkward, but there was no awkwardness in the way he moved. His monstrous head swung from side to side, with the great rows of teeth showing in the gaping mouth, and he left behind him a faint foul smell - I suppose from the carrion he ate. But the big surprise was that the wattles hanging underneath his throat were a brilliant iridescence - red and green and gold and purple, the color of them shifting as he swung his head.

I watched him for just a second and then I jumped up and headed for the time machine. I was more scared than I like to think about. I had, I want to testify right here, seen enough of dinosaurs for a lifetime.

But I never reached the time machine.

This is where he finds something worse and more disturbing than any dinosaur: an alien creature trained by aliens to herd dinosaurs, like sheepdogs herd sheep:

Up over the brow of the hill came something else. I say something else because I have no idea what it really was. Not as big as rex, but ten times worse than him.

It was long and sinuous and it had a lot of legs and it stood six feet high or so and was a sort of sickish pink. Take a caterpillar and magnify it until it's six feet tall, then give it longer legs so that it can run instead of crawl and hang a death mask dragon's head upon it and you get a faint idea. Just a faint idea.

The supercomputer in Keith Laumer's The Great Time-Machine Hoax (1964) shows off its powers:

...The view changed again. "In this igneous intrusion in the basaltic matrix underlying the Nganglaring Plateau in southwestern Tibet, I encountered a four-hundred-and-nine-foot-deep space hull composed of an aligned-crystal iron-titanium alloy. It has been in place for eighty-five million, two hundred and thirty thousand, eight hundred and twenty-one years, four months and five days. The figures are based on the current twenty-four-hour day, of course."

"How did it get there?" Chester stared at the shadowy image on the wall.

"The crew were apparently surprised by a volcanic eruption..."

cenozoic era

paleogene period

I doubt if the term "Paleogene" existed when Olaf Stapledon was writing, but nevertheless his tragic pre-human civilization of philosophical lemurs (see part 2 of chapter V of Last Men in London (1932)) would seem to have had its million-year career some time during this period. Up till now I had assumed the brainy lemurs to be late Miocene, about 10 million years ago, but rereading Stapledon's text I find that they existed "long before the apes appeared", which rules out anything later than about 25 million years ago.

...unlike the tarsier, it was prone to spells of quiescence and introversion. Fortune favoured this race. As the years passed in tens of thousands and hundreds of thousands it produced larger individuals with much larger brains. It passed rapidly to the anthropoid level of intelligence, and then beyond. Among this race there was once born an individual who was a genius of his kind, remarkable for both practical intelligence and for introspection. When he reached maturity, he discovered how to use a stick to beat down fruit that was beyond his reach. So delighted was he with this innovation, that often, when he had performed the feat, and his less intelligent fellows were scrambling for the spoils, he would continue to wave his stick for very joy of the art. He savoured both the physical event and his own delight in it. Sometimes he would pinch himself, to get the sharp contrast between his new joy and a familiar pain... One evening, while he was thus absorbed, a tree-cat got him. Fortunately this early philosopher left descendants; and from them arose, in due course and by means of a series of happy mutations, a race of large-brained and non-simian creatures whose scanty remains your geologists have yet to unearth...

The narrator, an observer from the far-future Last Men, praises the culture that eventually developed among the lemurs:

...They rivalled the ants in sociality; but theirs was an intelligent, self-conscious sociality; whose basis was not blind gregariousness but mutual insight. When they had attained a very modest standard of amenity and a stationary social order, their native genius for self-knowledge and mutual insight combined with their truly aesthetic relish of acrobatics and of visual perception to open up a whole world of refined adventures. They developed song and articulate speech, arboreal dance, and an abstract art based on wicker-work and clay. The flowers of personality and personal intercourse bloomed throughout the race... It might be said that these, who flourished millions of years before the Christian era, were the only true Christian race that ever existed. They were in fact a race of spiritual geniuses, a race which, if only it could have been preserved against the stresses of a savage world, might well have attained a far lovelier mentality than was ever to be attained by the First Men.

This could not be... When at last a submarine upheaval turned their island into a peninsula, the gentle lemurs met their doom. A swarm of the still half-simian ancestors of man invaded the little paradise... these fanged and hirsute brutes overpowered the lemurs by numbers and weight of muscle; by cunning also, for they had a well-established repertoire of foxy tricks. The lemurs had but one weapon, kindliness... Within a decade the race was extinct.

oligocene epoch

30 million years ago

30 million years agoFrom the description of a training camp in Time Patrol (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, May 1955) by Poul Anderson:

The Academy was in the American West. It was also in the Oligocene period, a warm age of forests and grasslands when man's ratty ancestors scuttled away from the tread of giant mammals...

It was a complex of long, low buildings, smooth curves and shifting colours, spreading over a greensward between enormous ancient trees. Beyond it, hills and woods rolled off to a great brown river, and at night you could sometimes hear the bellowing of titanotheres or the distant squall of a sabre-tooth...

It is discovered that the natives of the asteroid progenitor planet had visited Earth in the Oligocene in James P Hogan's "Giants" series.

Some way into The Nest by Poul Anderson (Science Fiction Adventures, 1953) it becomes apparent that Duke Hugo, the Norman brigand chief, has based his robbers' nest in the Oligocene after having seized a time-machine from visitors to his home in medieval Sicily. The tale narrates a revolt against his regime.

The Oligocene night was warm around us. A wet wind blew from across the great river, smell of reeds and muck and green water, the strong wild perfume of flowers that died with the glaciers. The low moon was orange-coloured, huge on the rim of the world. I heard a nimravus screeching out in the dark, and the grunt and splash of some big mammal. Grass whispered around our mount's legs. Looking behind me, I saw the castle all one blaze of light...

neogene period

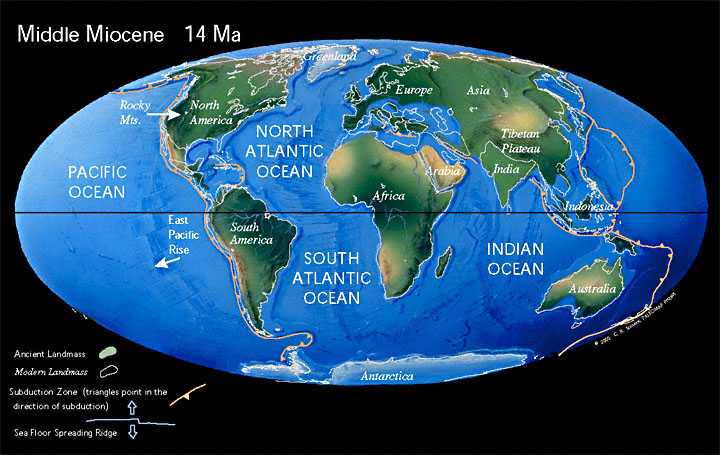

miocene epoch

In his short story The Miocene Arrow [in the anthology of Australian sf, Alien Shores, ed. Damien Broderick and Margaret Winch (1994)] Sean McMullen narrates the interaction between past and present, as the intelligent mind of a frozen cetezoid is restored after its death and that of its marine culture 9 million years ago.

...Cetezoid civilization had been based on a complex system of traditions, loyalties and associations, rather than cities and nations. Patterns of migration, lines of kinship, language groupings and teaching castes were the infrastructure of their society... Because they had no writing and all scholarship was carried in memories of individuals, teachers had a very high status. Their preceptorates had disputes, even wars, but the impossibility of artificial weapons meant that fighting was on a small scale...

...Then, overnight, tens of thousands of Western Preceptorate cetezoids beached themselves and died on the northwest coasts of the Pacific. It was a test and a warning: the Southern Preceptorate had a new weapon...

It's a mind-weapon, and the humans who resurrect "CM-Alpha" are disastrously unaware of it.

Back in the Miocene it was different: back then, as the story says in its opening sentence,

Armageddon passed unfelt on the land.

The rest of the opening paragraph sets the ancient scene:

...Slow global cooling was moderating the mid-Miocene climate, making it drier and sharpening the chill at high latitudes. The ice sheets in Antarctica expanded and became permanent, while small glaciers developed in Alaska and Siberia. Adaptable species had an advantage during the changes, while those which had fitted too well into fragile ecological niches went into decline. In Africa, several species of apes had learned to use stones to break the eggs of the large flightless birds, and sticks to extract honey from beehives. These were the most advanced tools in use on the planet, yet in the oceans two marine superpowers and a host of their allies were fighting the war to end all wars with no tools at all.

[Confusingly, it seems that The Miocene Arrow is also the title

of a novel by the same author, which however (from the blurbs I've read

online) does not seem to have the same theme as the short story.]

The epoch in question is the destination for Asa Steele, the protagonist of Clifford Simak's Catface (1978), when eventually he finds to his astonishment that he no longer has to rely on his alien friend to build "time-roads" for him; Steele can perform the feat himself:

Go ahead, I raged at myself, walk those few feet forward, tread that silly time-road. You'll see. There is no Miocene.

I walked the few feet forward and there was a Miocene. The sun was halfway down the western sky and a stiff breeze from the north was billowing the lushness of the grass. Down the ridge, a quarter-mile away, a titanothere, an ungainly beast with a ridiculous flaring horn set upon his nose raised his head from grazing and let out a bellow at me...

Earlier, we hear raised the question of opening the period for settlement. (Simak seems to have a rather odd idea of time - as though when you go into the past the causation you set off operates in a kind of parallel run with that of our present; thus, if you start a settlement 25 million years ago, it'll take 25 million years for its descendants to appear now... rather than immediately.)

"Asa, why the Miocene? Why not earlier? Why not a little later?"

"There'll be grass in the Miocene. Grass like we have now, very similar to it. Grass is necessary if you are going to raise livestock. Also, grass makes possible the existence of wild game herds... And in the Miocene, the climate would be better."

"How so?"

"A long rain cycle would be coming to an end. The climate would be drier, but probably still sufficiently rainy for agriculture. The big forests that covered most of the land area would be dying out, giving way to grassland. Settlers wouldn't have to clear forests to make farmland, but there'd still be plenty of wood for them to use. No really vicious animal life, or, at least, none that we know of. Nothing like the dinosaurs in the Cretaceous. Some titanotheres, giant pigs, early elephants, but nothing that a big rifle couldn't handle."

"Okay, you've sold me. I'll tell the senator..." [p236-7]

The Miocene is the intended ultimate destination of the refugees from the monster-ridden year 2498 in Our Children's Children (1974), another of Simak's time-related tales, in which the advantages of the period are discussed in similar terms to those later set out in Catface. In the earlier novel it's a case of finding a permanent haven because, as the refugees' spokesman, Maynard Gale, explains in chapter 11, they can't stay in the Twentieth Century - there isn't room.

"Where will you be going?" asked the President.|

"Back into deep time," said Gale. "To the mid-Miocene."

"The Miocene?"

"A geological epoch. It began, roughly, some twenty-five million years ago, lasted for some twelve million years."

"But why the Miocene? Why twenty-five million years? Why not ten million, or fifty million or a hundred million?"

"There are a number of considerations," said Gale. "We have tried to work it out as carefully as we can. For one thing, the main reason, I would guess, grass first appeared in the Miocene. Paleontologists believe that grass appeared at the beginning of the Miocene. They base their belief upon the development of high-crowned cheek teeth in the herbivores of that time. Grass carries abrasive minerals and wears down the teeth. The development of high-crowned teeth that grew throughout the animal's lifetime would be an answer to this. The teeth are the kind that one would expect to find in creatures that lived on grass. There is evidence, too, that during the Miocene more arid conditions came about which led to the replacement of forests by extensive grass prairies that supported huge herds of grazing animals..."

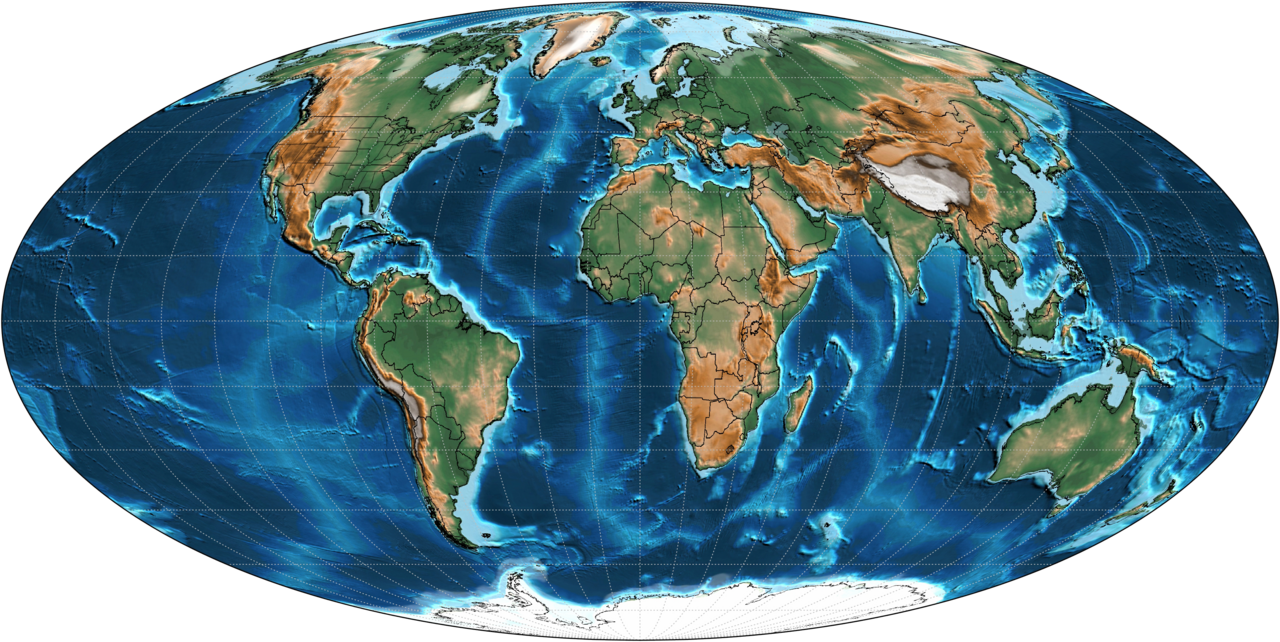

pliocene epoch

5 million years ago. You need to peer closely to see the differences.

5 million years ago. You need to peer closely to see the differences.The Pliocene is the setting for most of Julian May's mighty four-volume Saga of the Exiles (1981-4). To quote the blurb on my paperback edition of the first volume, The Many-Coloured Land:

The epic odyssey of the misfits and mavericks of the 22nd century who pass through the time-doors of the Pliocene Epoch into the battleground of two warring races from a planet far away...

(Note that although the epoch is referred to as the "Pliocene" throughout the saga, it is also stated to be "six million years" in our past, yet nowadays it seems that the Pliocene is said to begin more recently than that - the figure given by Wikipedia is 5.333 million years.)

Colin Wilson also has an idea of the Pliocene's dates which is somewhat at variance with the latest figures on Wikipedia - but no matter! From his Lovecraft-inspired novel of the Old Ones, The Philosopher's Stone (1969), p.234-5:

...What kind of civilization was it they built? I already knew, from the Voynich manuscript, that they had been responsible for the building of the legendary civilization of Mu, which may have been destroyed as long ago as six million years, in the mid-Pliocene. Mu was, of course, a civilization of men, built according to the instructions of the Ancient Old Ones: the "servants' quarters"...

Colin Wilson in the same book book provides a picture of the civilization of Mu learned through time-vision (p.247):

...Under

K'tholo, Mu reached an unparalleled prosperity - wide, smooth roads

running for hundreds of miles, reaching to every corner of the land, and

cities were built on huge level areas of ground covered with stone

slabs, engineered with such precision that there was no room for grass

to grow up between them. K'tholo instituted worship of the sun, to

counterbalance the worship of the dark gods, who were already haunting

men like a nightmare.

One of the most interesting and characteristic touches about Mu is

that it was a land of crickets. Because the climate was mild, and the

giant birds were more interested in small rodents than insects, crickets

increased in number until Mu became known as "the land of greeting" -

the Mu word for "hello" resembling a chirp. The people of Mu were born

and lived and died to the chirping of crickets...

Arthur C Clarke's initial drafts for 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) are collected in The Lost Worlds of 2001 (1972), comprising material which did not find its way into the final version of the book or the film. The section "First Encounter" narrates the creators of the Monolith's arrival at Earth and their initial impressions of our world.

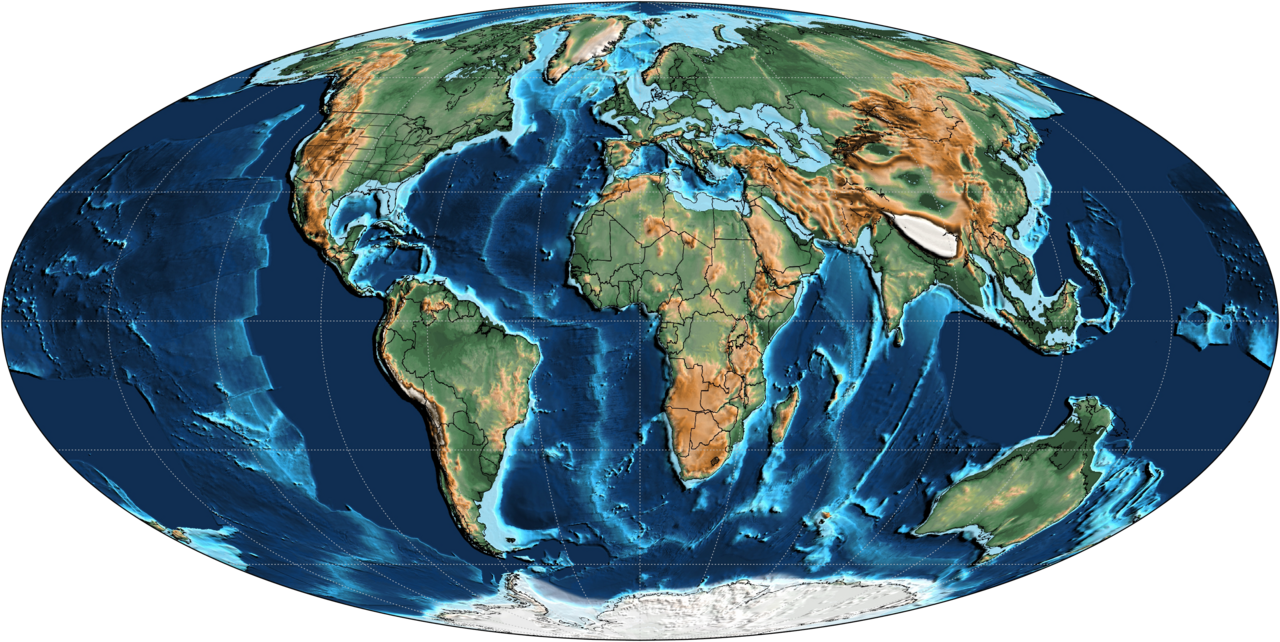

The glaciers had retreated now, and the shapes of the continents were much as Man would know them, when he made his first maps three millions years hence. There were, of course, minor differences; the British Isles still formed part of Europe, and the causeway between Asia and America had not yet crumbled into the islands of the Bering Strait. And the Mediterranean valley was still unflooded; the Pillars of Hercules would stand fast for ages yet, before the ocean broke through and the false, sweet legend of Atlantis was born.

And just what creatures will this world hold? asked Clindar as he looked down upon the turning globe. The great ship had come through the Star Gate only a few hours before, and the excitement of planetfall was still upon all its crew. Every world was a new challenge, a new problem, with its endless possibilities of life and death - and its hope of companionship in this still achingly empty universe...

A couple of chronological points:

I seem to remember that Clarke somewhere in this book refers to the "Pleistocene", but due to his date of three million years ago I have put it in this page's section on the Pliocene, which, according to Wiki, ended 2.58 million years ago. With regard to the flooding of the Mediterranean, Clarke is out by a few million years according to what I now read online; the Zanclean Flood is dated to about 5.3 million years ago, long before Clindar's arrival.

Poul Anderson is another writer whose chronology disagrees with the latest official limits of the Pliocene. However, in placing in this section the excerpt from The Little Monster (in Way Out, ed. Roger Elwood, 1974), a powerful short tale about a boy stranded in the far past, I go with the author's terminology: Pliocene it is, despite being only 1,500,000 years ago - because of the key sentence, "The Ice Age hadn't begun":

He hunched, hugging himself, in what little shelter from the cold a spiny bush offered. His clothes were only sport shirt, lightweight slacks, sneakers. Teeth chattered in his head. Spain of the Pliocene Period - No, wait; this land didn't look right for Spain - not the topography nor the wildlife nor - Well, Europe was supposed to be warmer now than in 1995. The Ice Age hadn't begun. If Earth had any polar caps at all, they were not large. That meant less rainfall in these parts, and no forests. Open grasslands would get hot enough by day but chill off fast after sundown...

quaternary period

pleistocene epoch

Asa Steele, having stumbled through a time gate, is mystified as well as dismayed, though he has recently met the marooned alien creator of time-roads, Catface [the 1978 novel by Clifford Simak].

Just standing there and worrying about it, however, would not solve the problem, would not give the answer. If I couldn't find the road back to the present, I might have to stay a while, and I told myself I'd better take a look around.

Looking in the direction the mastodon had gone, I saw a herd of mastodons, a mile or so away, four adults and a calf. The mastodon that had almost run over me clumped steadily to join them.

Pleistocene, I told myself, but how deep into the Pleistocene, I had no way of telling.

While the lay of the land remained unchanged, it had a vastly different look, for there were no forests. Instead, there was a stretch of grassland that looked somewhat like a tundra, dotted here and there with clumps of birches and some evergreens, while along the river, I could make out misty yellow willows...

Over twenty years before writing Catface, Simak had tried out some of its themes in a short story, Project Mastodon (Galaxy, March 1955), which is well worth reading for its own sake as well as interesting for its differences with the novel. No alien creator of time-roads appears in the earlier tale; a lone human inventor and his colleagues achieve the breakthrough, though at great cost, and only one person in authority gives them support - a maverick general, a rare example of a sympathetic military character in the Simak oeuvre.

...They had arrived at a time when the climate did not seem to vary greatly, either hot or cold. The flora was modern enough to give them a homelike feeling. The fauna, modern and Pleistocenic, overlapped. And the surface features were little altered from the twentieth century. The rivers ran along familiar paths, the hills and bluffs looked much the same. In this corner of the Earth, at least, 150,000 years had not changed things greatly.

Boyhood dreams, Hudson thought, were wondrous. It was not often that three men who had daydreamed in their youth could follow it out to its end. But they had and here they were.