red planet - heinlein's vision of mars

[ + link to the Heinlein Society's Red Planet Concordance ]

A classic of Old Solar System literature, Red Planet is Heinlein writing at his best.

Stid: The man is famous enough; why bother to add your voice to the chorus of praise?

Zendexor: Because he wrote so many books, and not all of them are classics. Even when you consider his juveniles - or "young adult" books I suppose they would be called nowadays - some are merely very good, rather than great.

After recently re-reading Red Planet I turned to re-reading Space Cadet, which belongs to Heinlein's same general period - just a year earlier than the other book - and the difference is considerable.

Space Cadet is well worth reading, it's enjoyable, it's full of interesting scenes and observations, the action and the characters and the background and the general ethos are all above par for the genre. Yet it's not special as Red Planet is special.

Stid: I'm not saying you're wrong, and I see the point of alerting readers who are new to Heinlein, so that they can head straight for the big stuff. But when comparing the style of the two books, I find it's the same old matter-of-fact Heinlein in both.

Zendexor: Yes, you won't find flights of colourful rhetoric in Heinlein; he doesn't gush, nor does he wax poetic by means of lilting sentence structures or figures of speech. Yet neither is he the least bit dull, at least, not in Red Planet. (Some of the technical instruction in Space Cadet is rather take-it-or-leave-it clunky-though-interesting.) What he does, like any good realist writer, is draw pictures in the reader's mind by means of observations drawn from a richly, deeply, coherently imagined world. He writes simple sentences embodying those observations.

He gives us believable characters. Likeable protagonists, and villains who get their comeuppance. School life on Mars. Beyond that, the adult world; colonial life and political revolution. The geography, flora, fauna and ancient civilization of Mars, as good as it's ever been done. What more do you want in 167 pages?

I particularly wish to contrast Red Planet with Farmer in the Sky. Again I must hasten to make clear that I'm not comparing good and bad, I'm comparing great with merely very good. By all means read and re-read Farmer in the Sky, as I have done, for its adventure, its realism, its imagination, its characters and scenes. But note, also, the way I struggle on my Ganymede page to squeeze out evidence from the text concerning the character, the feel, of the world, Ganymede. No such struggle is necessary for the reader of Red Planet. Heinlein's Mars is unforgettably, enthrallingly portrayed...

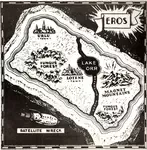

Harlei: Incidentally, Zendexor, it's a Lowellian Mars, surely the best example of the aerography of Percival Lowell being fleshed out into a story, as it were.

Chapter 2, "South Colony, Mars", contains the following description:

The surrounding desert, while beautiful, is monotonous. South Colony was in an area granted by the Martians, just north of the ancient city of Charax - there is no need to give the martian name since an Earthman can't pronounce it - and between the legs of the double canal Strymon. Again we follow colonial custom in using the name assigned by the immortal Dr Percival Lowell.

Zendexor: And it's probably just about the last time it could have been done - publishers (misled by the chronist fallacy) were soon to reject as "outdated" the old-style Mars with canals. Not that Heinlein's Mars is as unrealistic as Burroughs'. Barsoom has an atmosphere easily breathable by humans, whereas on Heinlein's Mars

the colonials maintained about two-thirds Earth-normal pressure indoors for comfort and the pressure on Mars is never as much as half of that. A visitor from Earth, not conditioned to the planet, will die without a respirator. Among the colonists only Tibetans and Bolivian Indians will venture outdoors without respirators and even they will wear the snug elastic mars suits to avoid skin hemorrhages.

misleading illustration

misleading illustrationSo, physically, that's the type of Mars we're given in this book. The Worn-Out Mars. Old, perhaps dying. But - this is the big "but" - the Martians, though few, are to be reckoned with. They play the key part in the story. And they are Heinlein's best alien creation by far. In fact, I'm not sure I wouldn't go so far as to say that his Martians are the best ever - even beating C S Lewis' in certain respects!

You may ask, are they friendly or unfriendly to Earthmen? It depends. They can help - indeed they can rescue - but they can also annihilate. They are profoundly mysterious. The chapter "The Other World" is as inexplicable-yet-right as anything in Tolkien.

Most, though not all, of the book is narrated from the young protagonists' point of view. But one of the "adult" sections is the last chapter, when old Doc MacRae, who speaks good Martian, tells James Marlow - the leader of the colonists' revolution against the autocratic Development Company - that he has managed to persuade the Martians (who have been enraged by the actions of some humans) to allow Earth people to remain on their world.

Marlowe got up and started to set up a wire recorder. "Do you want to talk it into a record and save having to go over it again?"

MacRae waved it away. "No. Whatever formal report I make will have to be very carefully edited. I'll try to tell you about it first." He paused and looked thoughtful. "Jamie, how long has it been since men first landed on Mars? More than fifty Earth years, isn't it? I believe I have learned more about Martians in the past few hours than was learned in all that time. And yet I don't know anything about them. We kept trying to think of them as human, trying to force them into our moulds. But they aren't human; they aren't anything like us at all."

He added, "They had interplanetary flight millions of years back... had it and gave it up."

"What?" said Marlowe.

"It doesn't matter. It's not important. It's just one of the things I happened to find out while I was talking with the old one..."

much better illustration

much better illustrationWhat is important is the way the Martians have - as it turns out - of dealing with people who try to harm their young. One such villain is Marlowe junior's new headmaster, Mr Howe, who confiscates the lad's pet "bouncer" - a cute little critter who, unknown to anyone, is the larval form of the adult Martian.

Earlier, the reader is shown what a nasty piece of work Howe is, as he tells off his pupils for painting identifying designs on their breathing masks.

"...Had you noticed what was posted on the bulletin boards you would have been, each of you, prepared for inspection. As for the dereliction itself, I want you to understand that this lesson far transcends the matter of the childish and savage designs you have been using on your face coverings, offensive as they were."

He paused and made sure of their attention. "There is actually no reason why colonial manners should be rude and vulgar and, as head of this institution, I intend to see to it that whatever defects there may have been in your home backgrounds are repaired. The first purpose, perhaps the only purpose, of education is the building of character - and character can be built only through discipline. I flatter myself that I am exceptionally well prepared to undertake this task; before coming here I had twelve years' experience at the Rocky Mountains Military Academy, an exceptionally fine school, a school that produced men."

He paused again, either to catch his breath or let his words soak in. Jim had come in prepared to let a reprimand roll off his back, but the schoolmaster's supercilious attitude and most especially his suggestion that a colonial home was an inferior sort of environment had gradually gotten his dander up. He spoke up. "Mr Howe?"

"Eh? Yes? What is it?"

"This is not the Rocky Mountains; it's Mars. And this isn't a military academy."

There was a brief moment when it seemed as if Mr Howe's surprise and anger might lead him to some violence, or even to apoplexy. After a bit he contained himself and said through tight lips, "What is your name?"

"Marlowe, sir. James Marlowe."

"It would be a far, far better thing for you, Marlowe, if it were a military academy." He turned to the others. "The rest of you may go..."

By the time the Martians get to deal with Howe, in their drastic fashion, the reader is all set to cheer.

But the Martians are more than just ruthless - there's a radically otherworldly side to them also. Young Jim and his pal Frank at one point find themselves among some Martians in one of their cities:

Several other Martians drifted in and unhurriedly composed themselves on frames. After a while Frank said, "Do you know what's going on, Jim?"

"Uh - maybe."

"No 'maybes' about it. It's a 'growing-together'."

'Growing together' is an imperfect translation of a Martian idiom which names their most usual social event - in bald terms, just sitting around and saying nothing. In similar terms, violin music has been described as dragging a horse's tail across the dried gut of a cat. "I guess you're right," agreed Jim. "We had better button our lips."

"Sure."

For a long time nothing was said. Jim's thoughts drifted away, to school and what he would do there, to his family, to things in the past. He came back presently to personal self-awareness and realized that he was happier than he had been in a long time, with no particular reason that he could place. It was a quiet happiness; he felt no desire to laugh nor even to smile, but he was perfectly relaxed and content.

He was acutely aware of the presence of the Martians, of each individual Martian, and was becoming even more aware of them with each drifting minute. He had never noticed before how beautiful they were. "Ugly as a native" was a common phrase with the colonials; Jim recalled with surprise that he had even used it himself, and wondered why he had ever done so.

He was aware, too, of Frank beside him and thought about how much he liked him. Staunch - that was the word for Frank, a good man to have at your back. He wondered why he had never told Frank that he liked him.

...The Martian who had left the room returned. Jim was sure it was the same one; they no longer looked alike to him. He was carrying a drinking vase. Frank's eyes bulged out. "Do you suppose they are going to serve us water?"

"Looks like," Jim answered in an awed voice.

Frank shook his head. "We might as well keep this to ourselves; nobody'll ever believe us."

Robert A Heinlein, Space Cadet (1948); Red Planet (1949); Farmer in the Sky (1950)

See the extract, Viewing memories on Mars.

For my grumble about non-availability of classics such as this, see Anomalies of the book trade.