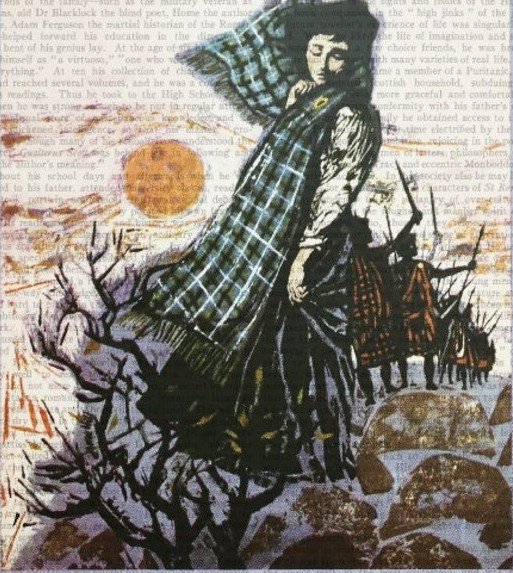

colonising genre-space:

jasoomian gathol's

royal drama

[ links to: Guess the Situation and Jasoomian Gathol ]

Those of us who are in the know, quietly understand that historical fiction is a kind of subset of sf...

Stid: Special pleading, Zendexor! You won't get away with it -

Zendexor: Let me finish. I did say "kind of". And you won't deny that the sense of wonder and the joys of a roaming imagination are common to historical sagas and sf.

Stid: I'll grant you that, but - what are you up to, Z? Are you about to lead a colonial movement to settle sf-fans in an expanded genre-area?

Zendexor: Wait and see. First, with regard to the general public, never mind sf: we've got to face the fact that there is a widespread phenomenon known as "not being interested in history".

Stid: You mean, the dopes who dismiss it as a frozen finished thing? Let 'em. Why bother with such people?

Zendexor: Because sometimes all it takes is a fresh approach. And for that purpose, I am about to present something new.

It's a presentation that draws its power from - guess what - forgetting! Temporary, selective forgetting.

Here's the idea:

Give the history-averse reader some historical narrative scenes that have been stripped of names.

The point of omitting the names? The answer is quite simple and powerful: drama is restored to freshness because, with the removal of the names, the usual boringness-buttons have been disconnected.

Stid: Hang on - why should names be boring?

Zendexor: To you and me, they aren't, but then, both you and I take it for granted that to read a name of a person or place, or a date (which as an identifier counts as a kind of name) is a helpful orientation rather than a trigger for an "oh, not that again" and a toss into the cliché-bin.

On the other hand just imagine for a moment that you're a sufferer from HAS (History-averse syndrome).

If you're one of those unfortunates, you only have to read the name of a king or queen or the date of an event in order for that section of your awareness to get immediately shut into a sort of frozen locker. "Charles the First lost his head and that's all done with." Never mind that no all-done-with Charles the First ever existed; that all times are present to those who live in them and past to those who come after them; that every moment shimmers with contingency... the HAS-sufferers don't get it.

But with the help of Guess-The-Scene, they may!

I plan to institute on this website a series on the lines of Guess-The-World, only focusing on the drama of British history. (It's what I know most about, and one has to start somewhere.)

In fact I think I'll call it Guess The Situation.

the reason for the focus on royalty

Some words of explanation:

The Guess-The-Situation entries will make use of crown-centred drama to an extent which may cause readers to wonder. It's limiting, but deliberately so. The use of a long royal line of descent is, in my view, analogous to that of a dip-stick used to stir a substance to test its consistency.

If we want to understand past eras, we want to know their texture as systems, what was possible and what wasn't... to assess how thick, how hard to stir the mixture was. How much scope existed for individual action to make a difference.

Now, the historian can't go back and try to do this himself. Time-travel (fortunately) hasn't been invented. But the next best thing is to study what stirrers did in their own times.

Rulers are perfect for this. Their egos were stroked and incited in most cases from birth. If anyone was likely to be inclined to test the bounds of the allowable, of the politically and socially possible, it was a monarch who owed his or her throne to heredity, and who felt the colossal sense of entitlement which a royal upbringing was virtually bound to instil.

Much of the drama springs therefore from the efforts of impatient royals to impose their will on the resistant fabric of society.

Have a go at identifying who, where and when!