Mervyn Peake: A curious stillness

a study by

antolin gibson

Mervyn Peake occupies a unique place in fantasy: the essence of his work is stillness. Perhaps his only counterpart in Science Fiction is Cordwainer Smith (with a dash of Alfred Bester?)

In the first of Peake’s Gormenghast Trilogy, it is the stillness of a world mired in ritual. In Letters from a Lost Uncle, it is the stillness of adventure – that is, conveyed by the suspension of a steadfastly rapt mind, always savouring the quintessence of the experience.

In Mr Pye, it is the study of the stillness of an obsession – and the petrification (stillness) of the reaction of people to it.

Mervyn Peake lingers over his characters’ mannerisms. Doctor Prunesquallor’s zooming in – and frantically holding on – to the remarks of his sister, Irma, is the stillness at once of despair, love, curiosity, and some kind of hilarity of abdication from all the aggravation he experiences. The Doctor occupies a haven of hilarious fatalism.

The Prunesquallors’ relationship in their enclosed little house within the ritual-frozen Castle of Gormenghast is an exquisite balance. The Doctor is the sister’s rock of security but the sister keeps him motivated just as much with her eccentricities.

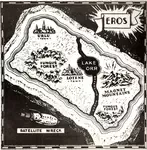

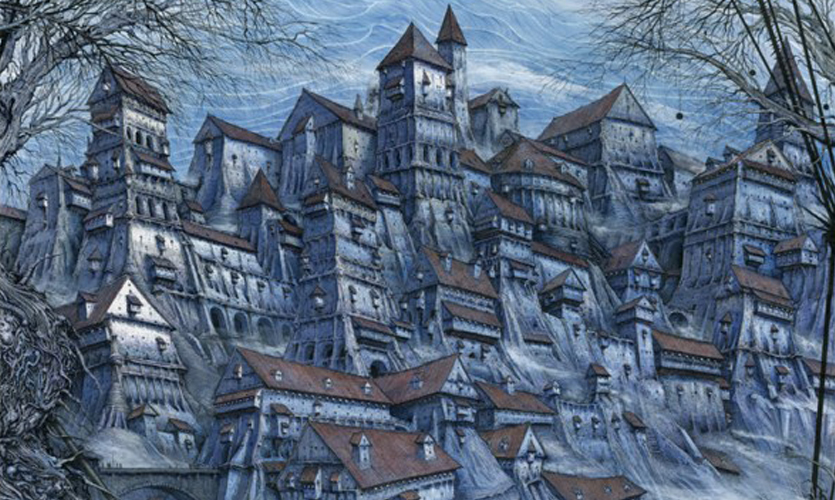

But then – in a curious contradiction to stillness – the universe of Peake is of environments bursting open: they do this because of the exuberance of the characters and the surrealism of the landscapes. Neither are artificially – stagily – exuberant. They conform to psychological truth: Lord Sepulchrave, in all the unforgiving weirdness of his surroundings, is utterly loyal to Gormenghast, but his sanity is only possible because of the escape provided by his Library in the East Wing. Considering how important the Library and the Tower of Flints are in the story of Gormenghast, the East Wing is surprisingly little known as an entity in its own right. That “Ichabod of architecture” is nothing less than an emblem of the history of the eccentricities of Groan.

But the escape provided to the Earl of Groan, Lord Sepulchrave, is a pathetically fallow resource. His madness is a tragic smashing-out of confinement – just as Mr Pye’s existential moral shift from good to evil, and the Lost Uncle’s search for the White Lion, are bravura and possibly mad attempts to smash-out. Steerpike’s attempt is, of course, exquisitely evil – and ironic. In escaping, he wants to pull the universe down.

Fuschia, the charming and brooding daughter of Lord Sepulchrave, has her Attic which, like her father’s Library, is a static resource like a dead-end drug, liberating but at the same time keeping everything as it is.

And with these two characters particularly in mind, I feel that there are few writers who have been able to view with such depth and breadth the transfusing dimension of loneliness. Mervyn Peak charts this dimension miraculously, in story-telling and startling poetic imagery, which can be shown for example in the haunting poem, “O’er Seas that Have No Beaches/To end their waves upon/I floated with twelve peaches/A sofa and a swan”. This brings to mind the author’s Letters from a Lost Uncle, one of his masterpieces: everything in the poem and in the letters from uncle to nephew is controlled, significant, and utterly serious. And thus, transported by the rigour and control of the author’s vision, the reader makes the startling discovery. Nonsense makes perfect sense. Nonsense is utterly serious in Peake’s universe.

There are so many branchings of stillness and reverie and explosiveness in each paragraph, and in each verse of a poem, the nonsense accompanies every action, in the author’s unique quirk of view, so that a tangled depth is achieved at every stage. Such as this, in Titus Alone:

“Without waiting for any orders from the brain a demon in his feet had already carried Titus deep into the flanking trees, and through the great park-like forest he ran and ran and ran, turning now this way and now that way until one would say he was irrevocably lost, were it not that he was always so.”

Titus Alone, Sixteen.

The stillness and entire seriousness of the nonsense in Peake’s branchings of the tale have their great emblem in a single fantastic image in Titus Groan – the tree that grows horizontally from the apartments of Lady Cora and Lady Clarice, and upon which they have their demure tea!

A crucial word on the “nonsense” of Mervyn Peake! Unlike Edward Lear and Lewis Carrol, there is mostly a tying up of lunatic threads – but, miraculously, this does not destroy the nonsense – but gives an effect, as it were, of a nonsense within a nonsense that makes sense. Something of this is shown in his poem I have My Price:

I have my price

– it’s rather high

(about the level

of your eye)

But if you’re

nice to me I’ll try

To lower it for

you –

To Lower

it! To lower it!

Upon the kind of

rope they knit

From yellow

grass in Paraguay

Where knitting

is taboo.

Some knit them

purl, some knit them plain

Some knit their

brows of pearl in vain.

Some are so

plain, they try again

To tease the

wool of love!

O felony in

Paraguay

There’s not a

soul in Paraguay

Who’s worth the dreaming

of

They say,

Who’s worth the

dreaming of.”

To write a critique of nonsense seems a violation – to try to make sense of nonsense would appear, after all, to be futile, far better to accept the mystic sense within, and in any case, it can be said for instance of Jabberwocky that the sounds of the words produce the sense, albeit a fantasy-sense, of sensation. While we are there in the nonsense, wherever “there” is exactly, listening to the blade swinging through air, observing the “galumphing”, we are no nearer to an explanation. Sometimes I think that – especially with Mervyn Peake’s wonderful nonsense – it is possible solely to find some dream within a dream, and from this species of “sense”, a note on Fable which – for Lord Dunsany in his beautiful A Shop in Go-By Street, is “co-eval with the “Elfin path” of fantasy. Mr Pye is a figure of Fable. At the beginning he is a personification of Good. But when he develops the physical attributes of Fable – angel’s wings, devil’s horns – he becomes human in his reaction. This bold experiment in the writing of Fable is, I think, unique, and the theme – via comedy – touches on Doctor Jekyll and Mr Hyde, which shows how serious Peake’s nonsense is:

“Perhaps I am a metaphor – and one day I’ll fit the thing I’m metaphorizing . . .”

Mr Pye, Chapter Thirty.

It is the quintessential utterance of Nonsense: a suggestion or image or theory that embodies the logicality of an illogicality.

Many regard Peake’s writing as Gothic but I would say it straddles the border between the dimensions of Gothic and Nonsense literature rather as Lawrence Sterne, and I can think of no other. The dark closes around, and anything can emerge from the shadows. But the great tradition of nonsense in English Literature, and surreal art, includes a violence of intellect which can very easily encompass a violence of action. The surreal Tom and Jerry cartoons have, as has been said quite often, an extraordinary amount of the most extreme violence, and other works for children are comparable – an acceptability achieved in a weird way because of the very fact that they are for children. (There is, if my recollection is correct, an interesting tale in Twilight Zone, the Movie which touches on this violence – about a little boy who holds adults in thrall by way of his mastery of a cartoon-world and its imposition upon the “real” world of drudgery). The violent art of Nonsense also finds a haven in children’s literature. If Peake’s Letters from a Lost Uncle is raw, then James Thurber’s The 13 Clocks is practically a survey of Stalinism. In fact, the Cold Duke almost outdoes Stalin, feeding his victims to the geese, and running people through with his sword, on the slightest pretext. The violence of this – as is true also of the Croquet-Party in Alice in Wonderland – achieves the necessarily hectic background to the classically calm nonsense-character and it seems that so many nonsense-characters are calm when one comes to think of it. The Cheshire Cat is one example of nonsense so great and calm, as is Peake’s wedge-shaped Poet on the roof-scape of Gormenghast, a kind of sense within the “non” is kindled which is wholly new and fresh, which I think Alice – and the boy Titus – both realize. In the case of the hectic and violent background of The 13 Clocks, it is the calm of the Golux that so coolly shines.

Of course such nonsense on film and in literature tries to tell a story, however secondary this may be to the madness, and in poetry there can be another and quintessential turn of the screw, so that a displaced truth is placed full-frontally before one, and then upon nonsense-legs retreats, and willy-nilly we follow tha elusive haunting thing:

The trouble

with my looking-glass

Is that it shows

me, me:

There’s trouble

in all sorts of things

Where it should

never be.

- The Trouble with Geraniums

And so the curious stillness and contradictory explosiveness in Mervyn Peake’s works are composed of Gothic and Nonsense. But the critic is drawn into pitfalls, by the fragile strength of nonsense in the telling of the tale. For nonsense to function, it has to make some kind of sense in the mechanism of plot. This can be helped by the drive of rhythm and the drawing of unlikely parallels. It can also, rather dangerously, be by the concoction of whimsy, easily formulaic, as appears in Roald Dahl.

Edward Lear’s The Owl and the Pussy-Cat skirts whimsy, hits the rhythm, and draws a tempting (although of course non-sensical) parallel. Thus, the Owl and the Pussy-Cat are so right for one another! Once the rightness is assured in the context of the nonsense, the context being a balance of elements which is fragile (and in which the miracle of genius has the greater hand) then the turkey can safely be allowed to marry the blissful pair. Parody falls generally to satire but in the hands of a master such as Edward Lear, and Lewis Carroll and Mervyn Peake, can illuminate and glorify nonsense. Peake is a unique writer of sustained nonsense literature, most beautifully seen in Letters from a Lost Uncle, which performs the miracle of a structured turmoil.

When all is said, nonsense naturally ascends to poetry and pictorial art. Lewis Carroll would be less without Tenniel, and Mervyn Peake was a poet and illustrator as well as a novelist – and the enhancement is not simply because of the additional genres offering a beguiling abstruseness, but rather they offer a focussing exactitude. There are excellent examples of this in Peake’s nonsense poetry – one of the best being Crown Me With Hairpins. But notice the restraint – ie, touches of normality – that can turn into the most uproarious nonsense in the context of the whole (thus: stillness, explosiveness, as I began by pointing out). Some themes seem to lend themselves to nonsense, even to the point of becoming some kind of code: such as hairpins – spinsters – aunts! From Betjeman to Wodehouse to Peake, such a code as this crops up. The border between Peake’s Crown Me With Hairpins and Betjeman’s Death in Leamington (Oh! Chintzy chintzy cheeriness/Half dead and half alive!) is but a tenuous border, after all.

To end with the most important consideration of all, which I hope will be found thought-provoking: Nonsense is a universe that NASA should seriously consider exploring. But will there be the funds, will there be the commitment?

And will there be the technological development of the sofa and the twelve peaches and the swan, to cross the seas which have no beaches to end their waves upon?

>> Authors