the mare frigoris culture

by

robert gibson

[ + link to podcast ]

Part I

The teacher's mouth curved in a sorrowful droop.

"I'm going to have to ask you to leave, Armando."

The boy stood up. "Now - signore?"

"Per piacere," nodded Signor Capuano.

That "please" impressed the class especially. The professore was such a gentleman, always.

It was a meek, biddable class, hardly ever restive even when Capuano insisted on dinning logic into them, as he had this morning - the grinding tedium of "if a=b and c=b then a=c but on the other hand if a=b and b does not =c, then a does not =c..." And when he put on his most courtly manner, he could sway their mood with ease.

Armando Ghirelli himself was the exception. The stocky, lank-haired boy was the only pupil not impressed, nor did he feel any embarrassment at being told to leave. Instead he looked bored, long-suffering, cheeks fat with the breath of frustration. Not the least bit guilty - though he had just caused plenty of distress by telling a pack of lies about what he claimed to have seen out of the window. As his teacher had expressed it more than once, the lad possessed the hide of a pachyderm to resist the pricks of conscience.

However, politeness prevailed on both sides of the dispute, for daily life in Base Uno was by and large a dreamy, feather-light, languid existence. Therefore, before turning to go, the delinquent shrugged a perfunctory apology:

"I am sorry, signor professore."

"No, you're not," Capuano grinningly asserted. "Mind you, I don't say that you are a vicious boy; only that the selfishness which is natural for people of your age, making it so hard for you to think of others as people in their own right, has in your case grown noticeably worse than usual. You're un diavolo innocente - you can't help it - but you and I must soon have a talk about how to undo the damage you've done. Meanwhile - out you go!"

And the teacher pointed at the door. Again, the class was mostly pleased. Michele's gang gloated, while Luisa looked distressed, but the majority were just quietly relieved that the trouble-maker had been shown the exit.

It was unnecessary to tell him to wait anywhere in particular. No hiding-place existed in Base Uno. Anybody could always be located within a few minutes.

When he was gone, the class collectively relaxed. All except the worried-looking girl, Luisa Alvaro. Small and dark-eyed, her black hair in plaits, she seemed, when quiet, to be younger than her age, but older when she talked.

"Signore," she pleaded, "would it do any harm to look into the matter..."

"Armando is the one who has done the harm," said the teacher firmly. Various mutters around the class supported this statement. "Certainly there is danger out there, but not the kind he is fibbing about."

"The Brazen Ones... could they not be responsible?"

"Luisa," said Sr. Capuano, "it is about five and a half thousand years since the Creation. We humans have come a long way since Adam and Eve; doubtless the Brazen Ones have gone further still, in ways of which we know not; but remember their failure down on Earth, where not even their armour sufficed for them. They are not shape-stealing monsters... they are God's creatures as much as we are, though they are perhaps our enemies; as, for example, the Milanese are often the enemies of us equally-human Florentines."

His words had their effect. He could sniff the emotions subsiding. The damage done by that scamp Armando was being undone...

Still, he'd better hammer the main points home, yet again.

"It is vital," he told them, "to keep the real threat in mind. Some day we will encounter the Moon-people. They are out there, somewhere, unless they are all dead - and why should they be? They're clever; clever enough to have built the ships to take them to Earth, to build the Cache which our Founder discovered. They've used their thousands of years since the Creation in spectacular ways. It may even be the case that they are not a fallen people; that they still inhabit their lunar Eden - though if and when we meet them, it is quite possible that they will seem severe to us, especially if they intend to exact a revenge for our... theft.

"But remember, that down on Earth they failed. They slunk back here, leaving their equipment behind, perhaps because they felt overwhelmed by the richness and variety of the world of Man.

"So remember, we must beware of them but not dread them. If we meet them we will find them clever, but not supernatural..."

*

Armando left the classroom with as much dignity as was allowed by the peculiar hop which was the only easy way to walk. Everyone he knew - the hundred and eighty-five adults and the forty-six children of the Base - pranced in the same ridiculous fashion; and it occurred to him just then, randomly, to wonder why, in that case, he should think it ridiculous; why, deep inside, did he know it to be unfitting? Ah well, just one more small irritation among many in an unsatisfactory existence.

But as for being expelled from class in disgrace, he did not mind that at all. He was happier outside school than in. Neither was he dismayed by the strictures, past, present or future, of his professore. The old teacher was harmless, and Armando had no fear of him or of anyone else in this narcoleptic community, where day succeeded day in somnambulistic stupor. As a matter of fact, if one had to be told off by anyone, it might as well be by Sr. Capuano who was less of an imbecile than most.

Armando hopped his way to a bench which was set back a couple of yards from the sloping outer wall.

Behind him, the curved inner wall ran its way around Base Uno, so that he occupied a place in the peripheral ring which, in the case of sudden air-loss, could be sacrificed - a possibility ever-present during the forty years of the Base's existence, but which had never come to pass.

Even if the risk were far greater, he was certain he'd ignore it for the sake of the view granted him by the magnificent window in the southward face of the dome.

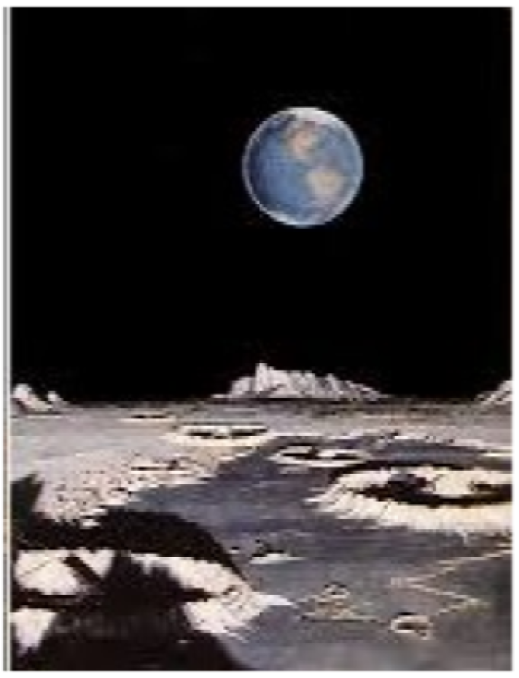

Through it his eye could escape metal floors and walls, and rove in nature's truth: a rocky plain, interspersed by wrinkles in the lava and a few jutting crags, and otherwise covered with dust, stretching to a close horizon.

Too close, he had always felt. In books he had perused drawings of scenes with ampler skylines: landscapes he'd never seen and would never see for real, located as they were on the great blue world which hung out there - right in front of him as he sat - its disk eternally almost grazing the southern horizon. Like a giant dream-bubble it hovered, forever on the point of settling onto the ground to invite its exiles back on board...

La Terra. Its blue of air and oceans spilled onto the different beauty of the moon, to stain with its cerulean tinge the grey of dust and lava, so as almost to convince the viewer, in certain moods, that the frozen rock-flow might actually be covered by a film of watery sea.

If the Base had been a little further north, at the Moon's very pole, Earth would perhaps not have been visible at all. And that would have left the heart of Armando desolate. As it was, he could dream.

He could dream vaguely and randomly, letting the thought-stream carry him where it would, or on the other hand he could dream purposefully, like an explorer planning his journey with strict attention to practical detail.

Today he found that his mood was purposeful. Wilful. As though just by thinking and wanting he might make a difference, even perhaps to the Base as a whole. As though thought and desire themselves had power...

But wait - wasn't that attitude more like magic than the true natural philosophy promoted by the Founder? Despite being a loner, Armando was at one with his fellows in his reverence for the Founder... The boy dithered like a hesitant walker at a fork in a path.

The soft thud of footsteps roused him from uncertain reverie.

"Ah," said signor Capuano, settling himself on the bench. "I guessed you would be here. You are a born observer. Mentally akin to our alchemists, who try to guess what is under the lava."

So, the professore had decided to begin with some words of praise. This was often the way he liked to build up to a rebuke. It was a game (Armando smiled to himself) that they had played many times before.

(Capuano, meanwhile, knew that Armando knew. In their decades of lunar isolation the people of the Base had grown thoroughly accustomed to each other's characteristics, to the various balances, reciprocities, social trades, carried out by each personality within the closed economy.)

Let's see whether I'm allowed a grumble, the boy decided.

"What do I care what's under the lava?" he scoffed out loud.

"Patience, boy, patience!" chided Capuano.

"But why must I be patient? I have no patience with alchemy! Our aliveness in history - that's what I crave - that's the door to all knowledge." And the door to life, exploration, escape. "So it's not what's underneath, it's what's on top of the lava that is significant, signore!" - and in the intensity of his next utterance his fingers stabbed forward at the scene beyond the quartz-glass: "Guardatelo!" - Look at it!

The teacher did look - it was impossible for any eye not to be drawn to the peculiarly littered area of plain, about half a mile from the dome.

"We've finished with that," he shrugged. "Our philosophers have no more to say. The topic is played out. All we really know from decades of studying that strewn mess of broken shapes, is that the Second Expedition crashed."

"Not even, that there might one day be a Third?"

It was Capuano's turn to scoff. "Possibilità - zero. Else it would have happened many many years ago..."

Armando, craftily, continued to play the game, by making a point which he knew Capuano would have to concede: "And yet we need not suppose that the Founder perished in the crash."

"Perhaps, indeed, he was not on the ship when it came down," the teacher agreed. "Perhaps he had sent it that second time under the command of another, while continuing his studies of the deposito segreto. Unfortunately there was just the one ship, and, when that was lost, no more travel between the worlds."

"But that means he may still be alive, down on Earth! His studies may continue, even now! He might still find another Cache, containing another ship," persisted the boy.

"Armando, be realistic," said the teacher. "This is Anno Domini 1543. The Founder was born in 1452; he would now, if alive, be over ninety."

Suddenly tired of the game, tired of the continuous circular tour of all the old arguments, Armando quietly switched to admitting that the Founder, though the most remarkable of men, was still only a man, who in fact had begun as an illegitimate nobody without even a proper family name: just "Leonardo from Vinci".

Moreover the title "Founder" was misleading. Despite all the man's genius, the lunar colony had not really been established with human tools at all. That was not where Leonardo's achievement lay.

It lay in the fact that he alone had managed to interpret and plunder for his own use the knowledge, powers and tools which he had discovered in the Cache.

The most treasured relic in Base Uno was a notebook, carried in the space-vessel that had brought the First (and only successful) Expedition from Earth. Armando had once gained permission to peruse it. Awed at the touch of a possession which the Founder himself had handled, he had pored over the strange mirror-writing which recorded the unique uomo universale's most fantastic discovery: relating how, at some point in his wanderings during the obscure years after he had left the service of the duke of Milan in 1499, Leonardo had traced from erratic compass-readings the location of a secret Apennine cavern, a hidden base hollowed out and stocked by ancient visitors from the Moon.

A few other scholars had been let into the secret, but none had been able to match Leonardo's capacity to understand what he had found.

Armando at that point heaved a sigh that was almost a hiss.

"Something troubling you?" asked his teacher in a silky voice.

The boy broke out with, "Why are we here at all? Here on this dry dead world? Why did the Founder choose such a place?"

Capuano merely shrugged. "Evidently, he wished to travel through the ether, and this was the only destination within reach of the power..."

"Yes, but why Base Uno? What I mean is, why spend that power on putting us here?"

"He must have had reason to fear what might happen if he did not use what he had found; he must have supposed that someone, or something, would seize the advantage if he did not, and would use it against him or against the people he knew or perhaps against all mankind. I speak only in the vaguest terms."

Vague indeed, thought Armando. Acceptable, inevitable, and in some moods quite likeable, that unfocused end of the spectrum of thought. Contrariwise he also appreciated the opposite, sharp, specific end, the detailed studies, the thousands of exact observations of each twisted bit of metal at the crash site: archives full of meticulous portrayals, drawn under various conditions of illumination and shadow during the long lunar day. It was a task for which the languid colonists had ample time.

What was missing, Armando sensed with frustration, was something in the middle: neither too specific nor too general. An aim to get one's teeth into, the teeth he was grinding at this moment! If only he had proper allies in this half-asleep place!

But the colony was full of meek people, who time after time dragged him down, so that whenever he surged again it was only the upward reach of a wave, a temporary clutching at vitality, always followed by a downward slide into supine passivity, after too short a wave-crest for a spirited boy to hurl any claim, brandish any assertion, create any havoc, blow any blast to shock away the smothering culture of Base Uno.

Whether it was the long-term effect of the strange lightness they all felt, or that of the month-long stretch between one sunrise and the next - aspects of life which seemed (paradoxically) both constant and strange - or whether it was something in the artificial air generated in the dome's unseen bowels, or whether it was none of these things but, rather, an adjustment of the soul to the situation - the inhabitants of Base Uno were almost continuously placid and crime-free. Anti-social behaviour was rare, and Armando Ghirelli was responsible for most of what there was of it.

But only when he was "uppish". Right now his mood was subsiding. He could sense himself sliding into one of the troughs, a passive vale between peaks of defiance.

Perhaps sensing that slump, the professore sezied this moment to abandon pleasant chit-chat, to shift the focus away from the civilized topic of history, and to nail Armando's guilt for what he had done in this morning's class. The hour of rebuke had struck.

"We shall now leave speculation aside. Right is right, and wrong is wrong. Even you," - and the teacher's tone plummeted, "never before had the bad taste to weave, into a lying tale, the objects which we do not mention..."

Armando shrank into himself.

"You," continued his teacher, "are like the boy in Aesop's tale, the boy who inventively cried 'wolf!' to frighten people... and when at last the wolf really came, nobody listened."

Armando put his head in his hands. If only they were on Earth, if only they could see real flesh-and-blood wolves. How could he have been so unkind, so stupid, as to tell creepy suggestive fibs about the bits and pieces of armoured suits, the half-buried fragments...?

Ah but they were ripe for it, those things! Debris of the crashed Second Expedition, in tantalising display on the dust-covered lava plain, as if inviting all the superstitious legends possible to the human imagination, the eerie litter had been sketched innumerable times from the south window but never examined from closer range, for nobody went out to poke around in it. Nobody, in fact, nowadays went out of the dome at all.

Theoretically it might be attempted. But if anybody tried to don the Moon-suits in the Base's storage vaults, they -

NO. One must not even think about it.

Even in his most rebellious moods, Armando knew that much; all the more reprehensible, then, for him to have told his damnable scare-story.

A tear of shame stole down his cheek. What an idiot he must have been, to fib that he had seen a fragment of a metal fore-arm advance in position amid the other wreckage on the lava-field! To suggest that the half-buried limb had swum a yard or two, in slow motion through the dust, towards the dome - how could he? It was planting the idea that the suits were being used, to clothe something infinitely worse than any wolf.

And yet - squealed nervy logic - the crash ought to have scattered the dust far from the area; how come, then, that on this airless world, the dust seems to have blown back, to resume its neat coating of the crash site?

The boy began to tremble and sob. Foggily he thought that it served him right, that the fear which he had tried to give to others now turned its claws against him.

But the temptation had been strong. A taboo asked to be smashed. Moon-armour! Say it out loud! But no...

It was never any use use trying to discuss the unmentionable topic in Base Uno.

Part II

The boy was not too young to understand the Great Problem. He had heard the smothered whispers, had sensed the repressed twitches of discontent.

Exiles have to have something to do.

By the time he began to use his young mind, scrutiny of the debris of the crashed Second Expedition had occupied much of the base's intellectual effort for decades; a field of inquiry that withered as the colony grew to accept that there would be no Third Expedition; so, what other project - the question was condensing like a storm-cloud – might possibly occupy their minds, satisfy their souls?

Apart from nostalgic study of the Founder's books, and the desperate hobby, increasingly popular, of drawing and painting on the walls... what real challenges remained? Logic might suggest that the mysterious technical contents of the Base itself should remain legitimate objects of study. The moon-suits in the vaults, for instance...

His teacher broke into his

thoughts – with a sharp voice that brought him back to the here and now, reminding him that he was in the middle of a telling-off.

"You don't need people, do you, Armando?"

"None of us, signore," the boy replied mildly, "need much company."

"Because of la languida, yes. The languor we all feel." A sigh. "Perhaps it is a drug in the air."

Wishing to sound bright, and to help with excuses, Armando suggested: "Or a taint in the idroponici, being Nature's revenge for the way we have to grow our food..."

"Ah, you've been listening to Signor Luzzatto! Our old 'farmer' with his perpetual grumble. But you, I suspect," continued Capuano in lowered tone while Armando's face fell, "would not need people even if you were to live on Earth."

The boy was silent. Perhaps that would depend on the sort of people, he did not dare to say.

Salvatore Capuano stood up to go. "Do not assume," he wagged a finger, "that our calm cannot be broken.”

“Signore?” stuttered Armando.

“I’m warning you that the people of Base Uno can be roused. And if la languida that protects them is thus destroyed, where will we be? Think about that, ragazzo, before you spread any more scare-stories." The man turned to go.

The boy called out after him, "Signore, you have made your point. I will co-operate!"

"Veramente?"

"Yes, believe me, I now realize, the only adventure I will ever get is through education."

"Hah! It seems that there's little I can teach you!"

"I did want to stir things, I admit - but only for adventure, you understand...?"

"Ahhh," - this came with a disgusted sweep of the arm which conveyed, I've heard enough. Over his shoulder the teacher added as he walked away, "Stay out of class - for, let's say, three days. I guess that may heal the damage."

Once more, the boy sat alone in front of the window.

And his thoughts, as they calmed, trickled back to the moon-suits…

*

Objects of superstitious fear, nowadays. But not always. After all, the things had had to be worn when the Base was being set up. People had had no choice, then, but to wear the alien armour.

In fact you could still see the boot-prints where the men had tramped the dust while positioning the installers during those fraught days, when (by some occult means) packs of alien workmanship had expanded into the dome they now inhabited...

Days of outside labour, on

the open surface of the Moon! No more,

though. Not for almost four decades now. The young folk had never been out.

Inevitable, that increasing reluctance to brave the air-locks. To

exit through them would necessitate the suits and helmets, and nobody wished to hear the

voices in the helmets. Mere mechanical echoes they might be, but the 'moon-ghost' Foa-oa-oa-donn, suspected to be

the real owner's name, was too disturbing, especially accompanied, as it was, by the odd reek of the suit-fabric.

Mind you, years had passed; the effects might have died down... but rather than risk it, it was easier, by far, to renounce the air-lock. Easier to stay indoors. Easier to vegetate and dream.

Besides, whispered something in the boy's mind, there were other ways to go outside.

*

With Capuano gone, peace and quiet once more reigned around Armando. As always, the view of the plain acquired for him a kind of silent voice, an invitation to that part of him which needed no suited protection, to come out and rove.

After more minutes had gone by, the peace held such sway, his teacher's visit might as well have never occurred. Instead, the vista through the window engrossed and swallowed one’s attention, so that to sit here and look was almost as good, or even actually as good, as flying out through the quartz.

What is aliveness? We say, some things are alive, and others are dead, but why this distinction? He found himself in a dreamlike argument with the landscape. It was as though it were making faces at him. Come on, it seemed to be saying; am I not the best companion?

Armando found his mind answering the "voice". Well... you see, there's Luisa; as often as possible I like to be with her, talk to her about the things that interest me, and she always listens, very patiently and kindly.

Oh yes? And what happens then? What happened yesterday morning during break-time, Armando?

I told her a little anecdote, from a Florentine history book. The passage concerned the jilting that began the long rivalry between the Guelf and Ghibelline factions in Florence. And presently, I spoke the line from Dante about the pietra scema, the "wasted stone", the scene of the Buondelmonte killing in 1215. Such a great world, Earth! So deep in happenings -

And how did she react to all that?

She heard me out, and then -

Yes, and then?

The landscape seemed to wait for his answer; with a vast and knowing compassion, it prodded his mind: What then?

Armando inwardly sighed.

Oh, she changed the subject.

Ahh… really you are alone, then. Nobody understands you.

But she's wonderful! I won't say a word against her!

The landscape said nought to that.

It simply surrounded his mind with its own beauty, as it surrounded the dome of Base Uno. The beauty, moreover, spoke a message: put not your trust in human beings. If you wish for freedom, splendour and power, place no reliance upon your disappointing fellow-beings.

Go down to the vaults. Put a suit on, and you’ll see what to do next…

No, he said. No!

He went on saying No – until the three days were up.

*

Really, the base was tiny. You hardly needed to walk a score of steps, before you reached the ramp that spiralled down to the storage vaults.

Still, those few paces gave you plenty to look at, if you had a mind to notice the art smudged onto the metal walls: decades of graffiti and finer efforts to while away the hours, days, years. The creation of beauty comforted the lonely soul.

Nobody

minded that the "paint" used for this artwork was not paint but a

vari-hued repair material endlessly replenished in a matter-converter,

surely for some purpose other than art. Just one of the

taken-for-granted wonders of the Moon-Men's skill... accepted because

one's life here was utterly reliant upon a support system of alien

construction and design.

Armando strode past some drawings which jogged his mind into remembering that those particular designs were by Luisa; they were her pride and joy. Remorse brushed him for a moment. That he had shown no interest in her art, was a matter for regret, but then again, she had shown none in his zeal for history. Oh, well... everyone was a dullard in some respects, himself included.

Convenient that he was encountering no one in this corridor... convenient, and no great surprise. The Base's population had steadily decreased during all of his short life. Those who remained were habitual day-dreamers, who shut themselves away in their cubicles for longer and longer hours. He thought little of them, although he sometimes admitted that he himself was not much better, sharing their enervated lassitude of body and mind; an odd sad contentment that dragged at him even now that he had resolved to change the pattern of his life -

From behind him came a concussing wave of sound. "Aieeee!" the girl's wail shocked him into a momentary freeze. "Non scendere lì, Armando!"

Luisa's agonized plea, don't go down there, almost altered his will. His numbed body teetered on the edge of the spiral ramp.

But

then he threw off the paralysis. He determinedly went forward and

down, racing - so he imagined - to outdistance her, and gasping as he

swallowed the truth of the situation: he really was going down where

nobody went any more. Then he realized that Luisa had not tried to

follow. She had turned back, doubtless to get reinforcements.

Authority would be along shortly, to stop him.

Well, they might or they might not. In theory he could still turn back, but really he had turned his corner of destiny for good or ill; he was committed... umm... except that he would have to turn back if the door to the store-room was locked! Here it was. A metal door. With a pasted-on sign: EQUIPAGGIO - USCITA.

Bound to be locked, unless -

Unless the last one out had left in too great a hurry. That was what he was counting on. Or did he fear it more?

He pushed, and the door swung inwards.

Even before he fully saw what he'd come for, he smelled them.

Never mind (his glance flicked hurriedly) never mind the chamber's other exits, all of them shut, leading to less interesting stores; this was the one, the place where They were propped or hung.

Silver

armour, some thin, some fat; some as long as two yards, some as short

as three and a half feet. The long ones, and some of the short, hung

loose and hollow; of the short ones, a half-dozen, fat and apparently

inflated, did not hang on the brackets but were propped stiffly, like ladders, against the wall. Quick, quick, think what to do!

Those six fat propped "shorties" were the Brazen Ones, labelled thus by folklore. Nobody had done anything with them, or seen any use for them. Unlike the other suits, they could not be opened; nevertheless in obedience to instructions deciphered by the Founder they had been brought back to the Moon along with other supplies from the Cache. Might they contain metal bodies, mechanical men like Friar Bacon's legendary talking head? Nobody knew. Armando's gaze slid away from them and to the other, taller suits. Those, the ones which hung thinly, were the ones he could, in theory, wear.

According

to the records of the colony, every single one of the suits had been

equally short when first found in the Cache on Earth. But those which

now were long enough to be worn by humans had got that way as soon as

they had been touched by human hands - had immediately and wondrously

adjusted themselves in a three-minute marvel of apparently magical

growth, if the accounts of witnesses could be believed. So those were

the suits that had been worn for the task of establishing the lunar

base. Essential equipment, they had been...

But the smell! Surely it must have got worse since those days, and in fact it seemed to be thickening by the minute even now! How could one make decisions or carry out tasks while shivering at the uncanny and indescribable? No word in Italian existed for what was not so much a disgusting as a fearsome reek; the 'tang' of a nightmare pull which threatened to draw out the entrails of the mind, assuring, I shall make you a new you; limitlessness will be your home. As though it might at any moment inject knowledge that the universe, instead of Dante's majestic series of concentric crystalline shells centred upon Earth, lit by the orbiting Sun and bounded by the Fixed Stars, were in reality a chaotic darkness, sprinkled with lost, wandering sparks. Oh, he ought not to have dared to come down here.

Especially he ought not to be here because of the clatter he now heard, descending in pursuit of him - he darted a backward look to see a grim-faced Signor Capuano loping to the base of the ramp.

Armando cursed himself for his inaction. By this time he ought to have put himself beyond reach of authority. He ought to have suppressed all fear, grabbed a suit, put it on and escaped out the airlock by now. Too late! Never before had he been in such trouble.

Then, as he glanced forward once more, terror smote him so that he swerved to being glad, after all, that Capuano had arrived: one of the Brazen Ones had begun to split down the middle. Motion where no motion should be. He heard a scream. Luisa had trotted in behind the teacher, and had seen what was happening.

Split further, the opened suit revealed an eyeless encased gnome, with a wizened, grinning, frozen mouth.

Non preoccupatevi, began the excellent Italian speech, the easy, colloquial, melodic familiarity that resounded in their minds from the Moon-man. Do not worry: you've simply gone soft, that's all it is; a transfusion, shall we say of mind-blood, will harden you again, amici! And then - ah, we've waited so long.

"'We'?" echoed Capuano in a croaky whisper.

Five

other short Moon-suits were also opening... or were they? No,

the first impression had been completely wrong: not one single suit had really "opened" after all; in actual fact their

surfaces still shone unbroken. Human eyesight had been fooled by crawling pictures shimmering over the suits' surfaces. Apparently the

"gnome", if it was a gnome speaking, was still shut up inside, but faithfully displayed by the moving image on the outside.

The three humans trembled at what they did not understand. One of them, however, - deciding that such mind-boggling alien chumminess must be resisted with dignity - grimly went into teacher-mode. This, thought signor Capuano, could be my hour.

*

"We are in the lunar sphere," the professore declared, "the humblest of the celestial orbs," he added to convince himself; "the sphere which revolves closest around the centre of the universe - Earth. And so, if anyone is to be master, it is we who came from Earth."

The Moon-Man's grin slightly widened. Continuate.

Capuano stuttered, "Q-quindi... therefore... this smallest, lowest realm in the lowest part of the sky cannot have produced anything that a man of Earth need fe-e-e-ar..."

The

two children looked up to him, for any comfort that might come from his words, in their need of a force to countervail the throb of

mirth in the mind-voice:

Bravely spoken, man of central Earth. Say more.

Capuano, though sensing a logic-trap about to close over him, stubbornly continued:

"This near side of the Moon shares the mutability of terrestrial life, which has allowed you Brazen Ones to make changes, perform achievements; but still the Moon is small, and you thus have less room than we. Furthermore, you've only had the same amount of time as we - only the same five and a half thousand years since the Creation. No wonder you failed when you tried to invade Earth. And only a few miles north from this spot lies the boundary with the lunar Far Side, where begins the true celestial cosmos, changeless, sinless, sphere enclosing sphere, out to the Fixed Stars and the Primum Mobile... You are caught in a very narrow place, Moon-Man."

Having said all this, Capuano's effort ran down. He exhaled. That was it. Putting Earth's case to the Outside...

A-quiver, the gnome's mind-voice replied:

"Teacher, you must un-learn so that you may learn. And you too, O bright and capable Earth-children, you also must learn in order to survive."

Perhaps at this moment noticing the stressed, swaying droop of the youngsters' bodies, the voice interrupted itself: "You feel weak and overcome, but la languida arises simply from the enervating lesser pull of an orb far smaller than Earth. By nature you are strong.

"And you need to know," it continued, "it is now time for us foa-donn to share with you our blood of the mind... We have waited MILLIONS of years for this!"

*

The shock of that dreadful quantity, millioni,

injected neat, in a mode that had to be believed, that could not be dodged or

misunderstood, was supernaturally terrifying. It killed their idea of the universe. Armando, Luisa and Signor Capuano suffered that death, suffered its replacement by the vastness of

Time, the chaotic decentralisation of Space, the banishment of their former Earth-centred vision, all of which wrenched their awareness into something unbearable.

They thus retreated from consciousness, while the lunarians got to work...

...Armando, when he awoke, noticed first that he was wearing a Moon-suit; next that he was hopping along under the sky; next that his gloved hand was holding another - and through the other's face-plate he glimpsed the tranced visage of Luisa.

He squeezed her hand as well as

he could, and received a faint pressure in response.

Ahead, the short form of the Moon-man was leading them in small hops over the dusty plain. Why? Where?

Perhaps such questions were unnecessary. The transfusion of "mind-blood" increasingly showed that a future beckoned, in which they, the strengthened lunarian race, could roam joyously across grey plains and mountains... could contemplate caverns... and await further visits from unsuspecting Earthmen in future centuries. All this, somehow, he had been taught in his sleep; the truth had enwrapped him. The others too, presumably. He turned his head and thought to recognize Capuano in the taller suited figure hopping a few yards behind him. All three of them were being led by "their" one Moon-man. A further five were nowhere to be seen; and this, too, was a fact which Armando did not question.

Capuano however accelerated forward, grabbed Armando's arm and touched helmets. "This is ridiculous," his voice carried through the armour. "Where are we being taken? There's no air on the Moon. We can't live out here..."

"Look at the light, signore," said Armando dreamily. "And the colours..." Smudges of red and orange and green, hints of impossible ghostly vegetation, wisps of air, images of aeons ago. "Flecks... I see flecks..."

"So

do I - pictures swimming around on my visor - it's all very

interesting, but we're getting low on oxygen and we can't live out

here!" Capuano spoke as one who desperately tries to reason with madness, and Armando listened, torn between two views of sensible reality -

A contradiction clanged into their minds. You

will not think so forever. More and more of you will come out, more

and more often, for longer and longer periods, until you are merged with us,

the foa-donn, the Morr Dlagga, the very last people of Yyu -

"But," pleaded Capuano once again, "we can't live out here!"

Soon, soon you will never need be inside. Oh, you may zig-zag back now for a little while to your Base. Its power-pack will last for five hundred years. But you will re-emerge in your suits, whose packs will last for fifty million years. To swarm, to look around, to remember - what other fate for you can there be, since you are here?

The icy shower of mind-speech thrilled Armando. "You - you can live in your suits? All the time? Awake and alive?"

The reply was prompt: We do not 'live in', we are our suits.

Armando grasped the proffered truth. Lunarian flesh and suits and souls had merged ages ago. And he perhaps caught an inkling of a final merger that was yet to come.

The 'gnome' turned as it spoke, and Armando and the others, as they caught up with it, saw its surface picture wink out of existence. No more moving picture of a living face. Only blankness. Gazing at that, they caught an inkling of what lay in store.

Ahead must stretch years of soundless resonance with the moonscape, after which their visors, finally unadorned, might gaze mutually at repose in metallic dark; and their sentience, soaked away into the environment, would tenuously persist in brooding plains and frowning rocks.

Death without oblivion.