tolkien - tangential wonder

by

antolin gibson

First of all, in my mooch about Middle-Earth, which I love, a confession. As to the mythology which is the background and resource of The Lord of the Rings, I’m not a huge fan. It seems to me to have one fatal flaw.

Of course, mythologies invariably have a flaw in creation built in as it were, to explain fallen humanity, and all the woes we are heir to. In the myth of Ancient Egypt, wicked Set tricks Osiris. In Greek myth, Pandora opens the box of evils. In Norse myth, the Trickster Loki brings Ragnarok. In native American myth, Coyote is Trickster and Clown. In Gormenghast, Steerpike escapes the hell of Swelter’s kitchens, only to spread ruin and destruction amongst all.

Morgoth by Justin Gerard

Morgoth by Justin GerardAnd in the myth of the Solar System itself, in what Olaf Stapledon calls “the everlasting tree of existence” (Last and First Men, Chapter XIV), time and again there is some fatal flaw that ruins any hope of a heaven upon earth.

In Middle-Earth, for sure, there is the fatal flaw of Morgoth, the fallen Ainur – no problem with that! – and his successor, Sauron – again, fine.

But there are also the Elves.

Celeborn by Ebe Kastei

Celeborn by Ebe KasteiOh dear.

The Elves . . .

whisper it: they can be a bit much

From age to age, tale to tale, there is the endless greed and stupidity of the Elves which bring ruin and destruction to all. While Tolkien admits the “weakness” of the King of the Wood Elves for gold and jewels, he hastens to say that the Elves are “good People”, as though hastening to convince himself of a rather wobbly concept. In The Hobbit, the weary company of Thorin Oakenshield are mocked by the elves of Rivendell who laugh like silly children at the beards of the exhausted travellers. In Lothlorien, Celeborn is portrayed as an unimaginative and pompous bore in his first audience with the grieving Fellowship of the Ring. True, he later apologises, but it leaves an impression of narrowness and stupidity.

What was Tolkien about? He himself would have fallen asleep after two minutes of Celeborn’s company.

My theory is, that it is something quite other than the Elves, and their centrality to the ages of the myth, that the author was truly interested in.

Because the truth is, the Elves are not particularly good people, whatever Tolkien himself says about them. Generally speaking, in the whole Mythos, they come out as galumphing, myopic, stupid, and catastrophic. But the problem is, they are indeed central to all the ages of the Mythos and no mere imp of mischief, no one-off unfortunate First Cause.

My confession then is – that I am not fond of elves! To which the answer might be, one is not necessarily meant to be, one just has to accept them.

maybe the Noldor had style, but...

maybe the Noldor had style, but...But the problem is for me that this aversion has been the obstacle to going as deeply into the background Mythology as I would have liked to go, because I get put off as soon as I meet an Elf. And I would have loved to have mooched through The Silmarillion as much as I have lovingly mooched through The Lord of the Rings over the years. For Tolkien has his own creation myth just as, in the fall of Sauron, he has his own Ragnarok and the ending of an Age.

going deeper

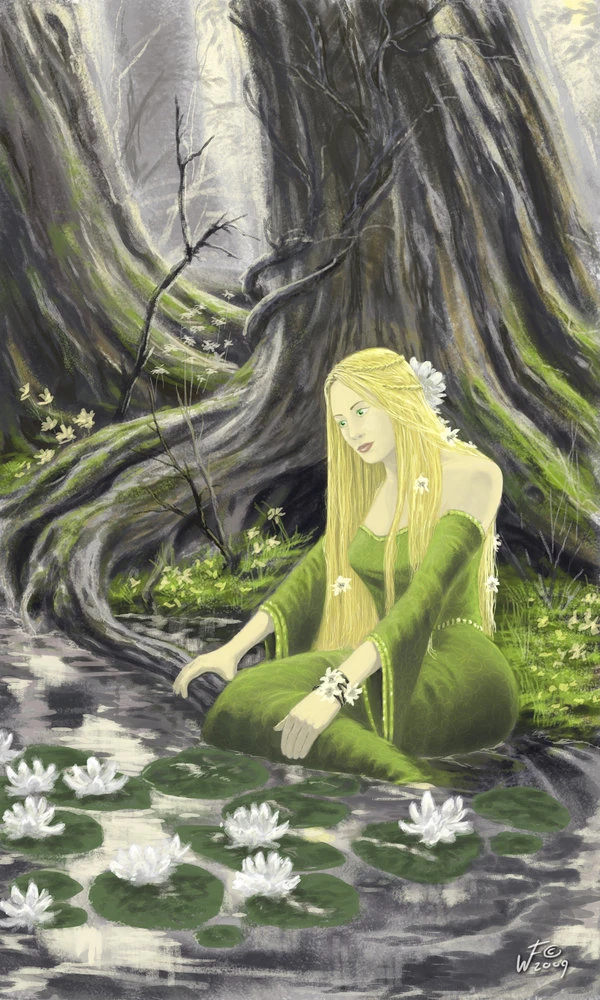

All this said, it is perhaps in the paradoxes within the system where are to be found the fascinating depths of Tolkien. Such as Bombadil. And such as the history of the Ents and the Entwives. Glorious paradoxes. The Entwives, although they are the gardeners, are the restless wanderers, and the Ents, although they are the shepherds, are the settled and spiritually rooted beings. In such ideas – quirky ideas! - the subtlety and freshness of Tolkien truly comes to view, not in the histories of the jewel-mad greed of the Elves. For Tolkien – when not being stilted into imperious action by the battles and greed of this Elder Race – is the very Cezanne of writers, his strokes broad and clear, such as this entrancing description of Goldberry in the House of Tom Bombadil:

In a chair, at the far side of the room facing the outer door, sat a woman. Her long yellow hair rippled down her shoulders; her gown was green, green as young reeds, shot with silver like beads of dew; and her belt was of gold, shaped like a chain of flag-lilies set with the pale-blue eyes of forget-me-nots. About her feet in wide vessels of green and brown earthenware, white water lilies were floating, so that she seemed to be enthroned in the midst of a pool. (Book I, Chapter VII)

Ursula K. Le Guin wrote an incisive appraisal of Tolkien which, I recall, highlights his genius for conveying ideas in colour and form, from which the manifestations of good and evil spring.

I think she makes a very important point – when I think of the Old Forest and the Barrow Downs, for instance, the former is painted in damp, sluggish, richly decaying strokes, the Forest’s drip-drip-drip in the sleepy stagnant hollows, the lazy dreamy pools, the ancient mind of the Forest biding its time. The Barrow Downs, by contrast, are full of clear cold edges showing through the mist, the glint of gold and steel and star; the conflagration of ancient wars, and then the cold:

“Kings of little kingdoms fought together and the young sun shone like fire on the red metal of their new and greedy swords. There was victory and defeat; and towers fell, fortresses were burned, and flames went up into the sky. Gold was piled onto the biers of dead kings and queens; and mounds covered them, and the stone doors were shut; and the grass grew over all. Sheep walked for a while biting the grass, but soon the hills were empty again. A shadow came out of dark places far away, and the bones were stirred in the mounds. Barrow-wights walked in the hollow places with a clink of rings on cold fingers, and gold chains in the wind. Stone rings grinned out of the ground like broken teeth in the moonlight.” (Book I, Chapter VII)

But linking both the Barrow Downs and the Old Forest is Tom Bombadil, with his voice possessing a joyful breezy undercurrent of pity both towards Old Man Willow and the Barrow Wights:

Lost and forgotten be, darker

than the darkness,

Where gates stand forever shut,

till the world is mended.

“Till the world is mended”. Those primal, brooding powers in Tolkien, of forest and hill, of hidden roots, await the mending, the healing of all creation’s flaw and the harm brought by the fallen spirit, Morgoth. Only that and nothing more. For the Elves, the very spine of the ages and the emblem of good, can be left to their greed and their jewels and their eternal squabbling amongst each other and with all the peoples of Middle-Earth. There are far more important things in Middle-Earth to experience.

tending value

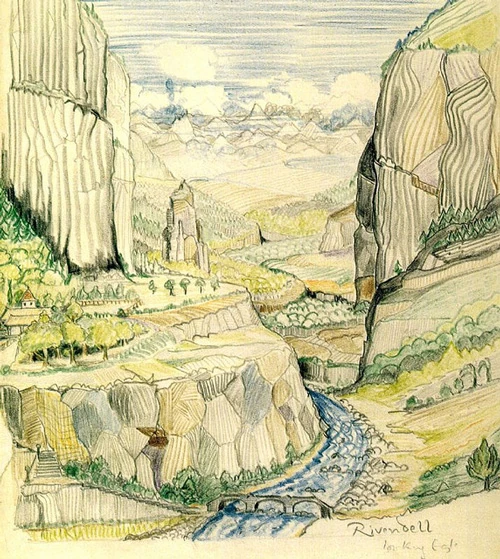

Most of all, The Lord of the Rings is to a great extent about the lonely custodians of value – Bombadil being one of the most significant, the Dunadain another. Bilbo, too, who valued the Shire more than anybody else, simply because he had his convention-defying adventure to the Lonely Mountain. And the Ents, custodians of the ancient Forest of Fangorn after the departure of the Entwives. Elrond of Rivendell, a place which somewhat gives the impression of a college campus and debating-chamber, is a flickering and uncertain custodian (Elrond is Half-Elven and thus much wiser than Celeborn of Lothlorien). It is in the House of Elrond, at the beginning of the great feast, that there is perhaps the first venture into the Heroic Style in The Lord of the Rings. Thus of Glorfindel, for instance: On his brow sat wisdom, in his hand was strength. Alas, this is also a decline in the subtlety and sensitivity of the author, but – and this is a big “but” – note the brisk transition from this Heroic Style to the author saying that Frodo felt rather out of place, a transition so deft, when Frodo scatters the cushions on his chair.

Not to say that the Heroic Style does not sometimes hit the nail on the head – such as:

Gimli ground his teeth. “This is a bitter end to our hope and to our toil!” he said.

“To hope, maybe, but not to toil,” said Aragorn.

(Book III, Chapter III)

The phrase “to grind one’s teeth” is hardly permissible in a book by E.M. Forster but in tales with an epic sweep such phrases go back into the mulch of originality and pace, just as the poetic formulae in Homer (“dawn with her rosy fingers”, etc) truly add to the vividness and reality of the fantasy, rather than detract from this.

And indeed, the Heroic Style of “The Riders of Rohan” is I think one of the greatest pieces in Tolkien, having all the pace and freshness that are typical of his best writing, and the awareness of the fine-drawn structure and the very lineaments of the wonderful world that is Middle-Earth. The fellowship of man, dwarf, and Elf is here movingly chronicled, mainly by their differences. In this chapter, Legolas is the saviour and redemption of all the Elves:

Only Legolas still stepped as lightly as ever, his feet hardly seeming to press the grass, leaving no footprints as he passed; but in the waybread of the Elves he found all the sustenance that he needed, and he could sleep, if sleep it could be called by Men, resting his mind in the strange paths of elvish dreams, even as he walked one-eyed in the light of this world. (Book III, Chapter III)

the landscape of mind

The chapter “The Shadow of the Past” shows the author’s greatest strength, and most sensitive touches. As Tolkien says in the Forward, it is one of the oldest parts of The Lord of the Rings. The very heart of the story is there, not only the historical depth, with the reaching back through time by means of the narrative of Gandalf, but psychological depth with the perceptive portrayal of Gollum and, with the unique gift of the landscape of fantasy that Tolkien has, the way landscape is subtly emblematic of psychological states. Thus Gollum looks downward, to the roots of things, instead of upward, to the sunshine in the trees. And thus the tunnels in the Misty Mountains become his mind: the covering darkness becomes the lies he tells himself to conceal his guilt and his wretchedness. The darkness helps him to live the lie. Gollum’s gnawing of bones and whimpering seem as one with the tortuous rock and the drip-drip into the lonely pool from the shadowy roof.

Gollum's journey commences by Frederic Bennett (detail)

Gollum's journey commences by Frederic Bennett (detail)Ursula K. Le Guin emphasised Tolkien’s gift of psychological insight by way of the environments of a fantasy-world – which environments enabled the author to construct and, indeed, experiment with, psychological situations. The obvious examples are the tragedies of Denethor and Gollum in The Lord of the Rings; the brooding loneliness of Turin in The Children of Hurin (edited by Christopher Tolkien); the contrasting studies of the brothers Faramir and Boromir in The Lord of the Rings; and perhaps most brilliantly of all, the character of Thorin Oakenshield in The Hobbit, a truly masterly study of frustration and pride and, at last, redemption. Thorin triumphs in a near apotheosis of the flawed hero with the child ego, moved by events rather than by introspection. The fact that it is through the devices of fantasy such as the Palantir and the Arkenstone and, of course, the Ring of Power that the obsessions and paranoia of Tolkien’s characters are worked through, is merely to say that the author avails himself of the classic props of the genre: magical artefacts! Sure thing - easy-peasy to shove in a magical artefact, but in Tolkien’s hands this is all about character, such as the tortured Denethor gazing into the Palantir, the anguished Gollum clutching the Ring on the edge of Mount Doom, Thorin’s thoughts gnawing at the very memory of the Arkenstone.

As a writer of fantasy, Tolkien’s uniqueness lies elsewhere than the Heroic Style in which the Elves with all their greed and narrowness belong: it is the tangential wonder, away from the Mythology’s spine, its heroic cord, its battles and politics. Far far away.

I think it is Goldberry, surrounded by lilies, welcoming the weary travellers, and this, I suspect, is where the author’s heart truly was.

For some remarks about Denethor, see the comparisons made at the end of the Diary entry, Portraying John Carter.