Valeddom

5: onuk

Jacko ceremoniously shook my hand, his face lit up with a grin which told me without words how great was this meeting of classmates upon a rock-billow in the wilderness of Valeddom. However, he looked askance at the other Nydrs; inevitably he wondered how they might react to his identity.

They simply stared. Just quietly, passively astonished at the revelation of yet another Earth-mind in their midst, they were too amazed to speak.

Well, they ought to be happy, thought I. For now they no longer had any reason to be suspicious of Tmaeu as a Vutuan. Go on, please, I urged them silently; you accepted me; accept Jacko as well. Else lack of co-operation will get us all killed.

Protest came, however, not from the Nydrs but from Mr Bryce.

“What the devil did you mean,” he exploded, “by holding out on us all this time? You must have been here ever since the bus crash. Every bit as long as we. Why hide from us?”

His anger was infectious so that I began to wonder, was I being gullible, bamboozled by the eerie quiet of this lonely northern wilderness into accepting anything that looked like a friend? If so, how ironic! – for back on Earth I had never been friends with Jackson, we were such different types. In those days he had been the tall, strong, confident one; he never did worry about anything, because wherever he was, he coped.

Except, as I reminded myself, that he’d failed his exams, and so he had had to repeat the year.... That’s the clue (tapped the drum-beats of hudar). The fellow’s lazy by nature.... and then he has to make up for it…

Jacko/Tmaeu now spoke with the object of defusing Bryce’s anger.

“I know it looks bad, Sir, but let me explain: it didn’t happen to me the same way it did to you. The crash threw me here, yeah, into a Mercurian body; but Tmaeu wasn’t a Dluku, remember; Tmaeu was – is – a normal Valeddomian with a mind in full working order. He did let me in (I’m just another aspect of himself, after all), but he kept control.”

I put in a question: “Was that horrible? I mean, for the Jacko ego to be trapped in the Tmaeu skull….”

“Hard to explain, but no, it wasn’t horrible, exactly…. To be frank, it suited me. I didn’t want control; I was happy to let him do the worrying.”

“So,” growled Bryce, “you’re saying, you didn’t make yourself known to us, on account of you didn’t have a say – you were just riding passively inside his head. Hmm.... and you preferred it that way.”

“Yep. No use denying it.”

“Well.... all right.... can’t say I blame you.... I could have done with a period of apprenticeship, myself.”

The next question was obvious. Bryce, however, hesitated to ask it.

Haffnem stepped forward. Her parents stayed back, recognizing that she had the special right to sort this out alone. She came to Jackson and took his arm lovingly, and put the simple question:

“What has happened to Tmaeu now?”

“Tmaeu, in a way,” said Jacko with a new gentleness, “has given up.”

Haffnem paled.

Jacko continued: “He will always be in here,” he tapped his head, “but he is now the one who’s just along for the ride. Sorry, but that’s how it is.”

All of us held our breath. Haffnem’s previous sufferings could not compare with this. Admittedly I, her brother, had also become an Earth-mind, but I had previously been lost to her anyway, when I’d become a Dluku. And so when she had found me awoken from the Dluku state, she had been overjoyed, for the fact that I had awoken with a somewhat different personality and different set of memories was a small thing to put up with compared to the boon of finding that I had awoken at all. But this more recent catastrophe, compressed into one sudden shock, hit her harder.

Jackson soothed, “Remember, your Tmaeu is not gone. Same soul! But...”

“Yes, but,” she echoed with a desolate sob.

“But,” he continued, “what with the weakening of Vutu.... I’ve, uh, bobbed up into the driving-seat.”

“I understand,” she said, burying her head in his embrace.

Fred Jackson looked around grimly at our staring faces. “And now it’s my responsibility – since my other self has passed all his knowledge onto me – to tell you that the sooner we put distance between ourselves and Vutu, the better. We should get moving, and fast. Time spent in discussion is time wasted.”

Fnekt asked, “Can you tell us why we should take your word for that?”

“I sure can. Think of it this way: I, Fred Jackson, unbiased Earth-mind, am telling you that the Vutuans aren’t kidding when they say keep away from Nought. You hoped that was just a ritual phrase? Well, it is an empty ritual – but it’s empty in a sense that should make us worry all the more. It’s a vain hope. Nowadays no one succeeds forever in keeping away from Nought. And when it finally gets you, when your chest-band runs down to zero, uh, that’s when you, uh, sing from the same sheet. Get me?”

We all swapped uncomfortable glances, and Bryce alone spoke:

“A group mind?”

“A group mind,” sighed Jackson/Tmaeu. “Ren has already told you that the Vutuans as individuals are more or less dead anyway. It is not they, it is the city that lives.”

“But.... I keep thinking of Hyth Siedr.... She seemed like an individual to me.”

Jacko shrugged, “I guess it’s, uh, a kind of mind-tax. You’re allowed to keep something, but a hell of a lot goes to the government. I don’t think any of us could stand that.” He paused, and none of us contradicted him. He continued, “I (as Tmaeu) ran away from it once. I’m not going back again. Nor should you.”

Bryce clapped him on the shoulder, while Fnekt, smoothing away his sour look, assured him that he withdrew his objections. Any risk was preferable to going back to Vutu.

“Then we continue northwards?” Bryce asked.

“For now, yes,” Jacko said. “It’s the only direction in which the Vutuans dare not follow.”

I spoke up. “Can you tell us why they dread the North?”

“No, not really. I can recite some meaningless names....”

Meaningless names were better than nothing. “Tell us, then.”

“Onuk, realm of the zitpoidl.”

“Is that it?” asked Bryce.

“Yep, that’s just about it. Two new words for you to learn.”

“But what, pray,” Bryce persisted, “is a ‘zitpoidl’?”

“You mean, ‘What is a zitpoid.’ ‘Zitpoidl’ with the ‘l’ sound on the end is the plural. Means ‘The stones-that-walk.’ I told you it didn’t make sense.”

Indeed, neither to me, nor to my fellow-Ixlians, nor to Bryce’s Jempeldexan memory-store, did the word mean anything at all; apparently, even to the Vutuans it was just one of those terms – common on a very old planet – that were worn down by thoughtless repetition to a mere nub of sound, bearing echoes of ancient emotion.

Jackson added, “Anyhow, I’m not that keen to find out.”

We all agreed that we could well do without an encounter with the stones-that-walk. Fnekt summed up our aims. “We take advantage of the prevailing fear, to go north to escape the Vutuans; but not so far as to meet these unpromising ‘zitpoidl’. When we reach this compromise distance, we circle round, find a route south and head for Ixli. The water-bottles and the berries in our bags will last us, we hope.”

Our chances of survival didn’t seem brilliant, but we couldn’t think of a better plan.

*****

We trekked. Gradually the terrain altered. The blue-black rock under our boots remained hard as ever but looked more doughy and bubbly, or whipped up into corkscrew spikes which leaned crazily in the aftermath of their primeval convulsion. Vegetation became non-existent. You couldn’t imagine any terrain less suited to human life.

Nevertheless at times we wondered whether some kind of trail was visible in this chaotic land. A trail leading north, marked out by pointers? Or a chance arrangement of rocks? Then atop one broad summit the arguments ceased.

A man-size figure stood ahead of us.

He had his back to us and his left arm out, with the palm towards us, like a traffic cop bidding us halt.

He stood very still, on a square slab which we came to understand was a plinth, when we realized that the man was carved from stone.

We advanced and came round to the front of the statue. Jacko said, “The Defender.”

The right hand held a carven energy gun pointed ahead; the face.... I had never seen such a noble face.... or rather I had, just once – during a holiday in Italy.

“Tell us more!” demanded Bryce. “Who was he?”

“We don’t know if he was a real person,” Jacko replied. “Maybe just an idealized Vutuan of long ago.”

Not much like the Vutuans of nowadays, I thought. Nor, indeed, did the stone hero remind me of anyone on Earth, except –

My memory flashed back a couple of years, to when I’d been taken me round some galleries and museums in Rome and Florence. I didn’t have much art appreciation at that age, but one statue, of a tall man with sword and shield, did really bowl me over. When you see him you know, if you didn’t know already, that a real hero is a quiet hero; just looking at him makes you want to be as fine, as modest, as unselfishly brave as he: one who can look deadly danger in the eye without a trace of macho posturing, with nothing but pure determination to fight evil and to protect the defenceless. And I remember he inspired me with the feeling that even I, if I were by his side, would dare to stand with equally level eye to face the approaching dragon. Yes, Donatello’s “Saint George” is everything a man should be; and now, here on Mercury, I was looking at someone who might have shared the same soul.

Whether the statue represented some real historical Vutuan, or whether it was just an idealization into which the ancient sculptor had poured all his notions of gentle valour, purity and honour, it showed what must have been the best side of the civilization that produced it.

But this Defender also had a message for us. His left arm clearly signalled, “Stop!”

If we took him seriously, we should not go any further along this road.

It was time, therefore, to decide that we had gone far enough north, and to implement that part of our plan that involved circling round to the east.

We didn’t want to trespass on the domain of the zitpoidl.

Turn east! my mind urged. An immediate change of direction is called for!

But we resumed walking northwards.

At first, I suppose, each of us thought what I thought: “Might as well go on a bit further without making an issue out of it, since the others have judged it wise not to veer to the right just yet.”

Next, the suspicion took hold, that this “just a little further” was going on rather peculiarly long.

Several minutes more went by before I admitted – and I presume the others also knew – that we were no longer our own masters; that we had come within range of a power that could compel us to obey its summons.

*****

At this point I must remind myself, the writer and you, the reader, of the purpose for which I am telling this tale: namely, to help others who may find themselves translated from world to world. It’s only fair if I pause here to issue a warning.

Vutu had been strange enough, but at least its inhabitants were human. Though (as I had finally realized) they weren’t conscious in the normal sense, and though I called the place a “nuthouse”, I nevertheless could recognize that in principle, given the time, I might be able to shine the light of reason upon the happenings there.

But – sorry about this – the murk definitely thickens from now on. Onuk, unlike Vutu, was not a human realm. It gave me even less opportunity than Vutu did, to use reason or logic while struggling through its thicket of events. And beyond Onuk, in the ultimate climax of my stay on Mercury (which occurred in a city that was human) I have to admit that in the end what got me through was pure hudar, and that must seem like cheating. Again, sorry!

So henceforth, though you can expect me to narrate what happened to me and what I did about it, and how I felt and thought about it at the time and later, yet for all my efforts, the world of Valeddom remains an impenetrable riddle, a jungle of mystery in which I never found a big enough clearing or vantage point from which to grasp the general scheme.

However, my rough and ready decisions, hunches, instincts, and ideas snatched in desperation, formed the machete with which I hacked my way through. Or to put it another way, I did, sometimes, make local sense of things – which is why I survived.

*****

Our neck muscles were locked so that we could not even turn our heads to share glances with one other as we marched; neither could we speak; we had turned into silent automata remotely controlled by an invisible power.

We were being made to follow what might have been the bed of a very shallow stream. If that's what it was, it was so ancient that, during the ages since the stream ran, the ground had been deformed by upheavals to form different slopes, which would explain why the route did not always keep to the gradient that a stream would have followed. But on the whole I suspected that this was no stream-bed but an artificial path: a route worn by the tread of the zitpoidl themselves.

We came into a region of harsher, craggier hills. They were perhaps only fifteen hundred to two thousand feet high, but because of their jaggedness I feel inclined to call them mountains. And on one of the peaks we saw what appeared to be another shining statue. This one was many times man-size, and not quite man-shaped: it was too knobbly, with exaggerated elbow- and knee-joints. Its head, lit directly by the sun, glowed like white-hot metal so brightly that I could not make out its features.

Just to the right of the peak on which that statue stood, there was a pass, and our route was taking us over it. As we approached, I kept upwardly revising my estimate of the knobbly figure’s size, until I concluded that it was sixty or seventy feet high. I wanted to examine it from different angles but the closer we got, the more it slid to the side of my field of view and as I could not turn my head I could not keep up my observation of it.

Just before my straining left eyeball lost sight of the thing completely, I glimpsed movement: the giant had begun a turning motion. It was slowly raising one of its arms. No “statue” after all, then. It must be a living lookout which had just announced our arrival to the other zitpoidl. My skin prickled; our fate was upon us.

We were mere seconds away from the boundary of Onuk, and in my mind I braced myself against the sight of something vastly alien and unknown which must greet us when we topped the pass.

We weren’t allowed to break our stride even for one second. Over that top and down we marched, without interruption now descending towards the floor of the valley spread out before us, two thousand feet below.

Far below, yes, that floor, but one outrageous feature stood already level with our heads. If you have seen prints of Breughel’s “Tower of Babel”, just imagine that Tower existing, real but magnified, and crawling with giants.

A broad spiral ramp took ten full turns to get from base to summit of the giant cone. On the ramp were moving several zitpoidl similar in size and shape to the lookout whom we had just passed. Some were ascending the spiral, some descending, but all of them, despite their giant size, strode several times slower than a human’s normal walking speed. I blinked at the slow-motion panorama and tried to comprehend sizes and speeds. The cone, I guessed, must be at least a thousand feet wide at the base, rising from the valley floor below us to its flattened summit two thousand feet higher. Nothing in the scene could help me to guess what this stupefying structure was for.

Other zitpoidl, apart from those on the conic tower, could be seen dotted about the valley. They seemed to be doing nothing much, and doing it very slowly. No buildings other than the great cone could be seen. Even the cone itself offered meagre detail; it seemed to have no door, no windows, no inside. If this was where the zitpoidl lived, they lived without shelter. But then, what shelter could a rocklike giant need? And what was the use of asking practical questions of a scene as fantastic as any dream?

We continued our descent by a winding path. It took us hours of trudging, but finally we got down.

No rest was allowed us. Our steps were immediately directed towards the cone. Weirdly, as we began our final approach to its spiral ramp, all the zitpoidl in the valley apparently began to accelerate their movements. Since I couldn’t really believe this, I guessed that not only our wills but our time-sense were now being tampered with so that actually it was we who were being slowed, we who were being altered to match the lesser speed of the giants. This change in our speed was giving us the illusion that they had increased theirs. They now seemed to move their limbs at something close to a normal human rate.

We reached the base of the “Tower of Babel”. As we all began to ascend I tried to jerk my eyeballs askance, for since I couldn’t speak – and how I longed to use my voice, to speak with my friends! – at least I might attempt to read expressions. It was then that I noticed the absence of any companions beside me. If I strained to listen I could still hear footsteps behind me, footsteps which I hoped were theirs. Evidently, for some reason, I had moved out in front. Was the summons specially for me?

Round and round the ascending spiral I marched towards the summit of the cone. The fear of heights would have got to me if the ramp had not been at least ten yards wide. On four or five occasions its stone surface trembled as zitpoidl strode past me on their way down. From close to, their huge bodies seemed more troll-like than ever, a mass of gnarls and knobs and flinty edges which nevertheless formed a kind of living tissue.

Such a climb, on Earth, at brisk marching speed, would have exhausted an athlete, but thanks to the strength of my Mercurian body I was still in good condition as I drew near the summit. I imagined that something would meet me up at the very top. In this I was wrong: before I got there, halfway round the last turn of the spiral, the force that had kept me going until this point suddenly held me still.

I stood frozen and helpless while my host loomed into view. He, or she or it, advanced down the slope to meet me.

This zitpoid was huger than the rest, perhaps about eighty feet tall. Finding at last that some control had returned to my neck muscles I managed to tilt my head up just in time to watch the thing stoop towards me, colossal arm outstretched, lumpy fingers holding a yellowish object that glittered like crystal – seemingly the twin of another crystal that the zitpoid wore on its own forehead. Meanwhile its other hand went round to cup me from behind, steadying me.

All my emotions were suspended; I did not know what to fear or hope or believe. If they had wanted to kill me they could have swatted me like a fly. And there was something so majestic about these zitpoidl, I could even forget to feel terrified.

The giant fingers that held the crystal pushed it forward, and I was held fast and couldn’t dodge and besides I might have hesitated anyway….hesitated to struggle.

When the gleaming stone touched my forehead, a buzz-z-z-z stabbed through me. My consciousness burst like a firework into dying fragments.

*****

I awoke, most comfortable, on a cushiony couch. In an innocent daze I contemplated two great windows side by side, oval in shape. Nothing but purple sky could be seen through them. This gave an impression of loftiness, perhaps of being on top of a tower.

The enormous room I was in was shaped quite like the inside of an astronomical observatory dome. Its swathes and shrouds of clutter, however, were unrelated to anything you might imagine from the use of the word “observatory”. Immense as the interior of a cathedral, and actually somewhat more than half a sphere, the place was sumptuous as a palace and as complex as an open-plan office. In fact it resembled nothing so much as a combined furniture store and carpet shop, criss-crossed with a maze of partitions about four feet high, while at intervals, like trees in parkland, taller furniture in the form of oversized hat-stands without hats, or mug-trees without mugs, stood hung with folds of tapestry so that some of them looked almost like wigwams. Festoons of fabric, red, blue, brown and gold, snaked like creepers from the “hat-stands” to connect at angles with chandelier-like structures dangling from the dome-roof….but perhaps, since I’m struggling to describe this textile jungle, I should leave off trying, and tell you instead what mattered more: tell you (if I can) how heavy with meaning it all bulged at me.

Not quite nightmare, it made me doubt that what I was seeing was honestly real. More like some kind of…. translation. If so, what was it a translation of? What was the original? Something I wouldn’t wish or be able to see or to make any sense of. Something that needed to be put into symbols in order for me to stand it.

I wasn’t scared – yet. Quite odd, my lack of nervousness; quite peculiar that I could notice those wigwam-things without getting too jittery about what they might conceal! Even when I looked up and saw isolated ripples running across the creepers of cloth, as though giant insects were pattering along their upper surfaces, I did not give the slightest shiver. How adaptable can you get?

It is indeed a great mercy that I did not guess the truth at that early stage. In fact I let nothing worry me, not even a certain sense of being watched, which was with me constantly, and which was to be expected in these circumstances of an entirely artificial environment which was so full of places of concealment.

Let watchers watch! It was good to rest. I didn’t care any more. I had had enough. For many minutes I reclined on the couch.

Natural vigour got me up at last. Time, thought I, for a bit of a wander.

My thoughts were calm with that mood of acceptance you can get in dreams. Yet as it turned out, I didn’t have to go far to meet my first disturbance. All I did was walk round the closest of the open-plan screens. Entering the partitioned space on the other side, I came face to face with a full length mirror.

It was placed as you will often find them in department stores, so that you meet yourself unexpectedly.

In that mirror I saw a short teenager clothed in school uniform. Hugh Dent, of Earth.

Ren Nydr, my Mercurian self, was gone.

*****

Of course I should not have needed the mirror to tell me this. Any time since I woke, a glance at my hands, at my arms with their jacket sleeves, would have given me the same information. Really my brain must have been in a vague state, to fail to realize earlier.

But what did it all mean?

I was dazed, but I wasn’t fooled. Not for one moment did I suppose that I was really back on Earth in my old body.

My dreamy frame of mind, and perhaps also my lack of an adult personality, worked to my advantage. I didn’t waste time considering the shortcomings of the evidence, I just knew that I was still on Mercury. The style of the room I was in was enough to convince me of that. Despite its separately familiar elements it was, in a subtle sense, quite definitely Valeddomian and not Terrestrial.

No doubt this would not have seemed like good enough evidence to Mr Bryce. He would have gone on about the need to consider the possibility of unfamiliar non-Western cultures on our own planet. But, as I say, I wasn’t grown-up. Didn’t need evidence. I knew.

As for what had happened to me – I did have one idea to go on.

I have mentioned the three great science-fiction stories set on Mercury. My view, which I still maintain, is that although these stories consist almost wholly of invention, there has been some leakage of truthful imagery via that same peculiar connection between the two worlds which resulted in my own adventure.

The Dlukus were mentioned briefly by Clark Ashton Smith, and the Brightside trip in the Vutuan Crawler had echoes of the tale by Alan E Nourse. Now I had encountered something which the third writer, Leigh Brackett, touched upon in “Shannach – The Last”.

The hero of that tale meets a life-form based not on carbon but on silicon; a being who is more or less made of stone. And the hero talks to this being by way of a crystal that transmits thought-waves....

It was a fair bet that when the zitpoid had touched my forehead with a crystal, he, like Shannach, intended some form of telepathic communication. And as in the tale, the method was likely to be something pretty strong. In fact, quite a lot more than mere communication.

Dominance. Command.

It needn’t necessarily be hostile in intent. But the natural differences between us, the enormously greater power and capacity of a silicon-based giant, were likely to lead to an extremely one-sided relationship. To put it mildly!

I looked around the furniture maze and thought to myself: I am probably being fooled in some big way, right at this moment.

Not that I believed I was dreaming, exactly. But – neither was it honest reality. Somehow there was a catch to it all. Perhaps in actual fact I was inside a special container for experimenting on humans.... but though it might be full of traps, I had no choice but to explore it, especially as I might find my family and friends somewhere around here. If they had been standing I would probably have seen them by now, for the partitions were low, but unconscious people, sitting or lying, would not be spotted so easily. I began to thread my way among the partitions.

My eyes darted around while I tried to watch in every direction at once, but, I told myself, at least I wasn’t scared; at least I had that to be thankful for....

I was heading in the direction of the two great windows, for I had a natural wish to see outside. Before long I found an L-shaped alley between the partitions, which looked promising. I turned the corner of the L and found myself in a larger-than-usual lounge, dominated on my left by the wall of the dome with the two large windows. But it was what lay ahead of me that skewered all my attention. For several heartbeats I forgot to breathe.

Comfortably relaxed on one end of a couch lolled Justine Lazenby.

Just as I was back in my old familiar body, so she was still in hers, wearing casual clothes of impeccable normality. And she, the regal, classy Justine who held sway as the reigning beauty of my class at school, was here with me apparently alone. In such astonishment as I had never experienced since I came to Mercury, I simply gaped at first, then dazedly replied to her smile of welcome with a hoarse “hello”.

She spoke:

“Glad to see you awake at last, Hugh.”

Awake? But surely this must be a dream after all, a wish-fulfilment dream. Whatever fantastic turn of events had brought us together, I felt as humbled by such awesome luck, as if I had won some cosmic lottery – and yet, and yet.... even in those moments I still knew on what world I was; knew I wasn’t back on Earth.

“Come on, Hugh, say something.”

I was still on Valeddom, and therefore so was she. The zitpoidl was playing its unknown game with us, and I must not forget that fact, must not relax, must not call it all a dream.

“You’re looking well, Justine. I’m so glad and relieved that you weren’t injured in the bus-crash.” I watched her face closely as I said this.

“‘Justine,’” she quoted her name. For a moment she looked blank. “Yes, that’s me! Funny, I remembered your name more easily than mine. On this world I am Nzaterpli. And you say.... there was a crash.”

I swallowed. “Yes, our coach hit a lorry, I think.”

With a sweet smile she said, “Oh quite, yes, of course, I wouldn’t be here, would I, if it weren’t for that?”

I stood and gazed at her in silence.

She went on, “Come and sit by me,” and she patted the couch.

“Sure – but just a moment,” I said. I wanted to check something first.

As I turned towards the daylight, I heard her get up from the couch and approach me from behind. When I reached one of the two windows, I felt her hand on my shoulder. We stood there, gazing out and down.

*****

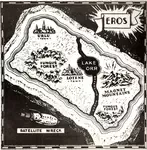

It was recognizably the same scene, the vale of Onuk and the giant conical “Tower of Babel” below us, but viewed from higher up. It was as though we were looking out from the summit of an extra structure built somewhere on the upper reaches of the great cone. That extra bit of height made a key difference. It enabled us to see over another pass through the western boundary ridge of Onuk and into Dayside.

This meant that we saw the sun.

Or rather, the half of it that poked over the Dayside horizon. That would have been quite enough, ordinarily, to destroy my eyesight.

These windows, I told myself, must contain a filter even more special than the one installed in the Vutuan Crawlers. At my ease I could contemplate the swollen Mercurian sun, seeing it as a deep orange-red, a beautiful ripe glow, quite bearable, though some aspect of this stronger capacity to see nagged at my mind, threatening to bring on yet another of those common Valeddomian bouts of suspicion. I didn’t mention it, for whatever it was I didn’t want it to cloud my conversation with the girl, who doubtless knew more than I did; let her comment, if comment was necessary.

All I said was, “Jus – er – Nzaterpli, have you learned where we are?”

“We’re standing on Pezerjink,” she replied without hesitation. “Close to the top of the spiral.”

“Pezerjink is the cone?”

“The cone, the city.” She turned away. “Come on, let’s sit down. I like comfort.”

I followed her back to the couch and we sat side by side.

“But though you call it a city, there are no buildings,” I pointed out. “Is the thing hollow?”

Not that I really cared about Pezerjink for its own sake. What I really wanted was to lead Justine on to reveal to me how much she knew and, from that, what her position was in the scheme of things around here. She seemed so calm, so at home, she must have achieved some position of influence and even power. This was a crazy conclusion, but I couldn’t get away from it; neither could I bring myself to ask her point blank, what have you become?

She tried to explain:

“Think of body-language, Hugh! The zitpoidl take it further: for them, walking is talking. A zitpoid’s changing position on the spiral, its moving address, is – location-language. Believe you me, one can contemplate it for hours. So don’t think Pezerjink is any less a city because it has no buildings. Every square inch of its surface is heavy with meanings, and the zitpoidl striding up and down the ramp may look purposeless to you, but....”

“Justine,” I cried, swinging round to hold her by the shoulders, “how do you know all this?”

Then, realizing I was manhandling her, I dropped my arms, shamefacedly; but she only opened her calm eyes a bit wider and said, “Why, how do you know what you know?”

“Sorry. I forgot. Of course, all this is an illusion. You and I are really in Mercurian bodies, and so we have access to Mercurian memories; we’re not, as we seem to be, wearing our old Earth selves. I suppose I was just momentarily glad to forget....”

“Understandable,” she nodded. “And why not? Why shouldn’t we relax, enjoy, forget?”

She seemed to mean it. My restless eyes flicked round the room but kept returning to her beautiful face. For longer and longer intervals they returned to it.

I sighed, “Look, let me just get some things off my chest before I relax too much, eh? I’m wondering what you’re here for, what I’m here for, and what we’re going to do when we meet the zitpoidl.”

On her face a gentle, amazed, pitying look appeared, which just for a second became withdrawn into blankness....

My tone became shriller as I ploughed on, “Has it brought us together so that it can use one of us against the other? Is it trying to get information out of me by the oldest trick in the espionage book, entrapping me with a beautiful girl? Or with the illusion of one – are you here at all, Justine? Am I under some drug? If so, I’m a bit disappointed in the zitpoidl. They seemed to be a high order of beings. And anyhow, why should they bother, powerful as they are, completely out of our league? Not that I want to ask all these questions, believe me; all I want is to forget them all and just enjoy being here with you.”

I slumped back, my head lolling on the back of the couch, my eyes closed. I certainly had said it all.

I felt fingers encircling my left forearm.

“Have you missed me?”

“Yes,” I said faintly, astounded at her question. We had never been on such close terms. Of course, when two people are thrown together by some hazardous chance, the situation can force them to get closer pretty soon, but I couldn’t believe this. Not of Justine. Something was wrong.

I heard her say, “Well, sometimes I feel a bit lonely too. That is why I summoned you.”

The scattered bits of the puzzle dropped into place, shocking my innards like a floor of a hidden lift going down; I scrambled off that couch, landed on my hands and knees, lurched erect and staggered over to the windows – those two big eyes that looked on the world from eighty feet above the spiral ramp of Pezerjink.

Among humans, you can get invited into a friend’s house. In Onuk, evidently, you’re in danger of being invited into someone’s head.

Justine and I were inside the zitpoid’s head. That was it. And not only that: Justine was the zitpoid. Nzaterpli the zitpoid whom I’d seen approaching from the summit – the chief of that race, I had no doubt.

I took a shuddering breath. I turned round again with my back to the window. She was still sitting on the couch.

“Are you all right now?” she asked.

When I said nothing she continued, “What happened to me is essentially the same as what happened to you. My mind was transported to another world, another body. Essentially, no difference. Just as your soul owns both Hugh Dent and Ren Nydr, so mine owns both Justine Lazenby and.... Nzaterpli.”

“Are you kidding?” I rasped. “Why should this silicon giant, this thing that’s not even the same kind of life as anything we know, why should it be one of your soul’s mansions?”

“Why not?”

“But for goodness’ sake, Justine, you’re human!”

“And so? What has species got to do with soul?” She let me ponder that one in silence for a bit. I couldn’t think of an answer.

I went back and sat down beside her again. Of course I now knew that this wasn’t what was happening. I wasn’t really sitting beside her. I was a web of mind-stuff occupying some guest-space inside the zitpoid’s brain, and Justine was occupying the host-space inside that brain. Neither of our Earth selves were here physically. Our Earth bodies, dead or alive (probably dead, killed in the bus-crash) were, naturally, on Earth. My Mercurian body was, I hoped, lying on the ramp below, where it had fallen at the touch of the crystal. And meanwhile our true selves, our awarenesses, were up here in the giant’s cranium, busy translating the truth into illusory sight and sound and touch. For example the giant’s eyes were turned by analogy into windows. That’s because windows are things we look out through. As for the rest of the stuff, the carpety stuff, I’d probably never know. I was willing never to know except insofar as I might find something we could use.

But what was the point of trying, hoping? What kind of trick, device or tool could a trapped mind use to escape from someone’s head?

You can’t get more caught than this!

A chuckle – it came from me.

“What’s the joke?” she asked.

“Well, um, you see, Justine, I always imagined you to be, shall we say, leadership material! I don’t exactly mean you were bossy.... but here you are, inhabiting the body of the ruler of the most powerful race on Valeddom.”

She gave a rich laugh, and hugged me. “You see – what did I tell you – it’s not what you are, it’s who you are!”

Heck, thought I, feeling the warmth of her cheek against mine – touching, seeing, what are they but signals in the mind? Does it matter how the signals get there? Why should I care about material “reality”? She’s right: substances, bodies, species, they’re all just conduits to the mind. One conduit is as good as another and what counts is who you are.

Besides.... another permission to put my arms round her.... this zitpoid has a brain so huge, its imagination’s strength and authority are so much greater than anything human, that I can’t believe Justine has filled it to capacity. She is it, but only part of it. She’s more at home here than I am, but I don’t have to identify her with the entire zitpoid. And as for the remainder – the part that isn’t she – well, don’t the shrinks of Earth divide our brains into conscious and unconscious, ego and id and whatever? Who knows what might be lurking around here?

That might explain why I still have a feeling of being watched.

*****

Sometimes I called her Justine, sometimes Nzaterpli.

When things got a bit political, I called her Nzaterpli.

“Tell me, Nzaterpli, what has happened to the others?”

We were walking hand in hand in the maze of partitions in the draped and festooned Enclosure.

I sometimes wondered what this walking around was a translation of. Perhaps it simply meant that our thoughts were churning, working hard. Or more likely it meant a leisurely opposite – thoughts drifting in a “walk” that was a pleasant illusion for its own sake.

I admit, it cost me an effort to do the decent thing and ask about the others.

“I didn’t summon any of them,” she replied with a shrug. “Maybe I will at some point. But you were the first and so far the only one I wanted to see.”

For the rest of my life I shall always feel honoured when I think of those words.

“Thank you,” I smiled, “for letting me be the first to get shown round your palace!”

She looked pleased, gracious and quite serious about what I’d just so lightly said. She always did have a bit of an imperial manner. Some might say it was merely the arrogance of an upper-class upbringing, but I never could stop regarding her as made of genuinely finer stuff than ordinary mortals. And now she was lodged as befitted her nature: inside a ruler’s brain.

I confess that I didn’t ask about the others any more. It was enough that she had said she might summon them some time; that assured me they were still alive.

For some hours I loafed, happy just to be with her, to stroll or sit, to look out of the windows and chat. They were the most blissful hours of my life so far. With anyone else I would have become restless, bored, anxious, or fearfully obsessed by the thought of the larger mental components of the zitpoid that were no doubt keeping watch on us both. But in the magic of Justine’s presence, I was content.

Incredibly, during this stretch of time I hardly ever stopped to wonder about practicalities. By rights I should have busied myself with important issues such as: is my Mercurian body (wherever it exactly may lie) being looked after? Will Justine/Nzaterpli ever let me out of here? Can she let me out? What would happen if I ripped some of these illusory fabrics into strips and made an illusory rope out of them and let myself out, assuming I can open the illusory window? When such questions droned by, I batted them away like midges. All I really cared about were the present moments of blissful companionship with the girl at my side.

However, this did gradually lead to deeper speculation about how much of the zitpoid she managed to fill. How much of its nature did hers occupy, and how much remained beyond her control?

In short, was she really in charge?

Highly relevant to the question of escape.

The scene outside the window-eyes wasn’t changing. The zitpoid therefore seemed to be standing still. Could she actually command the giant silicon body to move? Could she get it to issue orders to the other zitpoidl, even perhaps to do something unusual? If I pleaded with her, could she get us to Ixli – maybe accompany us there herself? I was most reluctant to bother her with these questions. Besides, to voice them out loud would be to take a sad risk. Not yet, I said to myself. Sometime I would have to face what had to be faced, but not yet, please, not yet. Let the golden idyll continue a bit longer....

Besides, after a further while, without me having to ask, some clues began to appear, as to how things were managed.

We were sitting together tranquilly on the couch, in a very human cuddle with our arms around each other, when suddenly her head went up and her eyes went cold and she stared at an object fixed high on the dome wall between the two windows. Rectangular, portrait-shaped, the object displayed a whirly diagram. I hadn’t taken much note of it before, but I now realized that the diagram had slowly been changing, as slowly as the hands of a clock –

It came to me that the thing was a clock. An Onukian time-piece. I’m just talking about how it looked, of course. In reality, like everything else I “saw” around here, it had to be some organ in the zitpoid’s giant brain, and I supposed it was an organ of time-sense, but to us – that is, to our minds lodged inside that brain, where perception was by means of symbols – the thing appeared as a clock.

“You worried about the time?” I asked her.

“Something I must do.”

She disengaged herself from me and went over to the wall. Her hand reached to take something from the wall – a phone! I was sure there hadn’t been any phone hanging at that spot before and now I realized that my mind was “ad-libbing”, creating symbols at need.

She spoke into the phone and her voice all of a sudden blared in a tongue unknown to me, whose syllables might have been produced by the grinding roar of slabs of rock that smite as they tumble against one another in a quake or an eruption. Those sounds were so harsh, they were unutterable by any human mouth. It reminded me that despite my sight of her lips moving, it wasn’t any real mouth making those sounds. But the essential point was, her will was giving orders to the zitpoidl, in zitpoidl language.

The roar ceased.

Having spoken to her people, Nzaterpli came back to sit down beside me, smiling her sweetly reassuring smile.

“Merely a preliminary announcement,” she said. “Setting in train the partial meld. Poor Hugh – you don’t know what I’m talking about, do you? Sitting there so patiently. As a reward, I’ll explain, though actually it doesn’t matter much.

“A mind-meld,” she went on, “is what happens when several zitpoidl focus their mental powers together to achieve a task that would be beyond their powers individually. For reasons which would mean nothing to you – because they are based on our special culture of location – we are building a tunnel from Dayside to Nightside. We are doing it by pure mind-power, which is slow but sure, and our life-spans are such that it does not matter how many ages it takes to build.”

As her explanation proceeded, her human voice and expression became gradually more remote, the Justine-section swallowed up in the whole Nzaterpli.

“Just now I gave orders to confirm the initial, partial meld. In about a minute, twenty of my people will hurl their combined mental force against a particular location underground....”

We waited and then I felt the tremors. It was just as I had sensed them while I and my companions were walking north from Vutu. The shaking of the ground transmitted itself up through the zitpoid’s body and into the interior of its head, where the symbols in the translated scene all caught the idea: the hangings and drapes and festooned fabrics set themselves to quivering.

It only lasted a few seconds. Quiet resumed.

The girl’s face looked satisfied.

“That was a trial probe for the next big advance,” she explained, her look and tone still enlarged with the aura of the whole of Nzaterpli. “Now there will be some tests made.... and then if all seems well, the main meld, the total meld, will take place. I myself will participate in this.”

“Justine,” I asked, “what will happen to you? Oy! Justine!”

She reacted as I had hoped. Her face softened at the sound of her Earth name. It once more became believably human.

“You’re asking what you will ‘see’ me do, and I can answer that. You will see me fall asleep. That’s how the meld will translate itself.”

“And what of me?”

“Do what you like, while waiting for me to wake up again!” she said merrily. “View it as a holiday from my chatter, if you like.”

“How long will I have to wait?”

“I don’t know. It’s going to be an important meld, a long one. It’s never possible to predict.... But never fear, it won’t be too long....”

It was bittersweet, but fortunate for me, that for all her confidence, all her contact with the vast wisdom of her zitpoid self, she nevertheless did not get the brute fact that I wanted the meld to be long.

For I had come to a decision. Instead of trying to win her over, I was going to have to act without her.

Something I must do, she had said, giving me a clue to the limitations of her authority. She could give orders to do what must be done. Perhaps also, as an individual, she might contribute to policy, but I guessed that her power, like that of a ruler of an ancient land bound by its laws and customs, had little leeway. And maybe this was true in more ways than one. In the less important and less interesting sense (as far as I was concerned), it was most likely true of Nzaterpli’s political position among her people. In the much more important and interesting sense (for me), the “constitutional monarchy” idea was a true description of the role and scope of Justine’s mind among the other areas inside Nzaterpli’s brain.

That was why it was no use me hoping and planning to win her over, to help us all escape. Her zitpoidl self couldn’t do it, and her human self was as trapped as I was, though more contentedly. She didn’t really have the power.

I had only myself to rely on. I must learn as much as possible before she “fell asleep”. Which might happen at any moment. What could I ask? What did I need to know? What didn’t I need to know about this fantastic land of Onuk and the ways out of it?

“Tell me,” I said hurriedly, “what’s at the very summit of Pezerjink?” I had an idea that it might be a vantage point from which to survey the realm. In which case I needed to know whether it was possible to get up there without encountering some typical Mercurian surprise of the kind that blows one’s plans to smithereens.

She was quite happy to answer me. After all, how could she suspect I had a practical end in view? How could I, mere mind-stuff in a giant zitpoid brain, get out and use any knowledge she gave me? For neither Justine the Earth-girl nor Nzaterpli the silicon giant knew anything of what was beginning to thrum inside me, the faintest of drumbeats of intuitional power that comes and goes in only a very few Valeddomian humans, the faculty of hudar.

Justine said, “Oh, there’s not much to see up there. The summit is occupied by the Lake of the Ancestor. Nothing else.”

“The Ancestor?”

“The Ur-Cell,” she explained. “The oldest lannemilb.”

“I don’t know what a lannemilb is, Justine.”

“So you don’t. Well, to help you believe what I say, remember that the silicon ecosystem is about as far from Earth’s carbon ecosystem as you can get.”

“I certainly realize that,” I told her. “Go on.”

“The lannemilb are the protozoa of the silicae....”

“Protozoa? Tiny things?”

“No. Unlike the carbon protozoa, these one-celled silicon organisms aren’t microscopic; in fact they’re as big as a carpet. And they don’t die of old age. The very first one, out of all of them, is still alive.”

“The Ancestor,” I said.

“You understand,” she said.

I understood more than she ever knew. Hudar had risen to a tinny and scratchy scream. Eerily it was answered by the trilling of the wall-phone.

Justine jumped to her feet with heartbreakingly lithe teenage energy and skipped to the phone. She unhooked it and listened. Then she straightened and those awful zitpoid-tones issued from her mouth. She was, I guessed, giving orders for the main meld to begin.

When she stopped, she turned and came back to the couch, her face softened once more into humanity, and I would have liked, more than anything else, to spend our final moments together saying a proper goodbye.

But I hardened my heart, for I had to make sure of one more thing.

“There’s no, er, chance, that I will find myself participating in this meld?”

“No possibility whatsoever. You’re nothing to do with the zitpoidl. Goodnight, Hugh.”

I saw her eyelids droop as she spoke.

I have wondered ever since about her last words to me. Was she encouraging me to escape? It’s a nice thought. But, not knowing how much of her was still human, I couldn’t count on it; I couldn’t confide in her.

Her head sank, her limbs flopped. That moment, the tremors resumed – the entire room began to shake once more. The far-off underground explosions created by the zitpoidl were coming up through the floor with far greater violence than the previous time. I sprang up from the couch.

What tensed me most, was that I half expected release there and then, for hudar had suggested that when Nzaterpli’s mind was occupied elsewhere, I might find myself outside, back in my physical Mercurian body. Well, that didn’t happen. Hudar nevertheless drove me on, hinting that I ought to give matters a push. It was now or never, while the zitpoidl drove their excavations further for their incomprehensible purposes, for who could tell when they might do so again? Across the shaking floor I ran to pull down some hanging festoons, knotted the ends together to make a long rope, tied one end to a pillar, then seized the nearest piece of moveable furniture, which happened to be a chair, ran to one of the windows and hurled the chair at it –

Never would I have dared but for hudar. Even with hudar I felt as an ancient Greek or Roman might have felt while risking the anger of the gods.

The window smashed like an ordinary window, but I don’t know that this meant anything much. Similarly when I threw out one end of the rope and began to climb out and down, I don’t know that it meant anything, in reality, except as a sign of my determined will. For I had hardly got my swaying descent underway, when a dizziness overtook me that wasn’t anything to do with the fear of heights. It was more like being dissolved. Dismissively dissolved with an “all right, all right, you’ve made your point.” And the next thing I knew, I was lying on my back on the ground, in the body of my Mercurian self, Ren Nydr. I could have screamed with glee – I was outside, out, out, OUT! Though at the same time, I was awash with regret.

*****

The sturdy legs of Nzaterpli, chief of the zitpoidl, rose like a pair of gnarled tree-trunks beside me. I looked up past them, all the way to the head, and found it hard to resist the thought, “Wow, I climbed all the way down from there.” Of course this was not true. I hadn’t climbed down. No rope dangled. There never had been a rope, a climb. I had never been up there physically; only (“only!”) my mind. I had willed myself out. For that, a “wow” was perhaps in order.

The ground-tremors continued, but down here on the stone ramp of Pezerjink nothing was flimsy enough to get shaken, so nothing visibly moved except the unconscious bodies of my companions lying around me: Bryce, Jackson, Fnekt, Opavedwa, Haffnem, all quivering slightly in the artificial quake. I got up, went over to each of them in turn, felt their pulses.... To the inhabitants of this land they were mere litter; they hadn’t been harmed.

I alone had been of interest to one....

And I guessed that the other zitpoidl didn’t know this, and that this was because they didn’t know about Justine at all. All my plans – if you can call them plans – were based on the idea that the zitpoidl were ignorant of the fact that a human mind had entered their chief.

I could have asked Justine about this, while I was with her, so as to make sure, but I hadn’t dared to arouse her suspicions. I hadn’t been able to make up my mind to trust her.

My tough Mercurian body now had some hard work to do.

One by one I must drag the bodies of my companions up to the very summit of Pezerjink. And then, seize what I dimly reckoned was our one chance.

*****

The most stressful part of it was in not knowing how much time I had. I was worn down more by that tension than by the physical effort involved in lugging five people up the rest of the slope. While the tremors continued I felt safe, but the moment they stopped, it would be a sign that the mind-meld was over and the zitpoidl would become aware of what I was doing. With all this, I didn’t even have the comfort of a believable objective – just the hint of a crazy plan. Hudar is a most uncomfortable gift; it may get you out of tight spots but it does so by giving you the thinnest of clues to follow. In that kind of situation it’s hard to believe that you’re not just behaving like a fool.

I could have stayed where I was, I could have stayed forever with Justine....

That thought threatened to sap me. So, in order to stay on course I began talking to myself as I lugged the first body – that of Bryce – up the slope, entering into an imaginary argument with my old teacher. “What’s this Ancestor up there for, anyway?” “How should I know? Sacred remnant of evolutionary origin, maybe. Didn’t dare ask. Didn’t dare show too much interest.” “Well, but couldn’t you have waited to make your move? Waited till you knew more?” “The zitpoidl are so slow, I might be dead before they had revealed enough.” “You wouldn’t die, not stuck up there in the giant’s brain. You’d live for ever.” “My body would rot, though. And so would yours.” “All right, point taken. So what are you hoping for?”

I shut up. I had reached the summit of Pezerjink.

Just one sweeping glimpse was all I allowed myself before I rushed down for the next haul.

*****

Thinking about what I had seen at the summit, I experienced a squirt of understanding, enough, just barely enough to keep me on the job. There’s hudar for you!

The significant sight had been of a circular pool perhaps twenty yards across, and, floating in the pool, a bright blue disc four yards across and maybe a foot thick.

Not much more to tell. Darker stripes round the disk’s edge, like the striations round the edge of a coin. Otherwise, featureless purity like the smooth surface of an egg.

And it was moving. My glimpse had not been too swift to spot that. It could move! The Ancestor – the oldest lannemilb, progenitor of all other silicon cells and thus of all silicon life – swam slowly round and round that pool. Not far from the edge. Reachable. Alive.

Awesome enough, but what made me shiver with extra hope, was the extra understanding that came to me when I pasted a further memory alongside all of this.

The balpars! Those frisbee-shaped floating platforms used by the people of Ixli – they also were lannemilb.

Or to put it the other way round – the Ancestor could be used as a balpar.

Any reasonable person could have posed dozens of objections to that. Fortunately there weren’t any reasonable persons available for conversation as I finally laid out the last of my companions on the lip of the pool and splashed in to grab the side of the oldest living thing on Valeddom.

Under the continuing influence of hudar I muttered, “Oldest – and highest.”

I was very much aware of the solemnity of that summit pool. The water, I guessed, was as much venerated as the Ancestor itself. In fact I suspected that the cone of Pezerjink had been built to that particular height expressly so as to preserve a memory of the altitude of sea-level at that time, billions of years ago, when life first appeared on this world. “So what?” you may ask. How was this fact supposed to be important to me? How could it help me in my mad attempt to escape from Onuk?

Hungry to see the answer, or to make an end of daft hopes, I waded round to the opposite side of the Ancestor and pushed it towards the edge. The lannemilb was smooth to the touch like commercial plastic. It offered no resistance to my efforts to deviate it from its course. It was only a mindless cell, after all. And fortunately it wasn’t very heavy.

I pressed down on my side of it so as to make the other end rise and slide over the lip and partly out of the pool. Then, keeping very careful hold of it, I let it down so that it was not quite level, one end on the slightly raised lip. I got myself out of the pool and took up the raised end of the Ancestor and pulled, so that the Ancestor now scraped forward over the dry surface towards the edge of the cone – the steep drop over the side of Pezerjink to the surface of the valley two thousand feet below.

If hudar was just a rubbishy delusion, I was about to commit what might have been the most sacrilegious crime in the history of Mercury, by hurling the Ancestor of all life down to destruction.

I pushed on and the front of the lannemilb went over the edge –

And floated in mid-air!

Full of wonder and triumph and gratitude, I yet told myself that I could still lose everything through one careless move. The problem was to position the Ancestor in the right way, so that I could load my companions onto it and push off, without letting the thing float off before I was ready. If I loaded it with their bodies while it lay on the hard surface, I’d never be able to push it off with all that weight on it. On the other hand if I let it float too soon, it might float away.

I solved the problem by using the heaviest of the bodies – Fnekt’s – as a sort of anchor, by putting him half on the lannemilb and half on the edge of Pezerjink, hoping that he would hold the lannemilb where it was by friction.

Then I loaded the others on. Then I inched Fnekt a bit further on. Then a bit further.... Fnekt was now fully on, together with the rest of us.

Then I had to act decisively and fast.

I would have given much for a steering pole such as is used on a punt. As things were I had to create momentum by taking a run and jumping on to the lannemilb. And I had to aim the jump so as to get the Ancestor going in the direction I wanted it to go right from the start, for I had nothing to steer it with.

I had done with thinking. I went back about ten steps and ran and jumped on.

The ancient lannemilb with its human cargo moved smoothly and steadily through empty air, out from the edge of Pezerjink.

It’s fortunate that my Mercurian body had a good head for heights....

*****

But how had I known, or how had I had reason to hope, that the Ancestor would float on air as well as it had floated on water eons ago?

Well, the balpars used by the Ixlians floated on air, and they did so at a constant altitude. I am sure this was the Mercurian sea level at the time when they evolved.

During the ancient days when Mercury had not yet ceased to rotate, the Sun, still shrouded in the cosmic clouds from which it formed, was just cool enough to allow an ocean to exist on its innermost planet, though it was boiling steadily away. At the time of the Ancestor, the beginning of life, sea-level was at its highest, the altitude of the summit of Pezerjink. And because location has such peculiar importance to silicon life, the Ancestor remembered, in the very fabric of its being, that level on which it was wont to slide. As time went on, its descendants likewise remembered the various lower sea-levels of their births. And “remembering” to them means something more than it does to us. It means that all lannemilb keep to their birth-levels, though the sea has since departed from them and, in fact, has now altogether ceased to exist.

But how does all this work, and why are silicon beings so linked in meaning with location anyway? I suppose you could say that silicon life is more a matter for the physicist than for the chemist. In other words, whereas here you have biochemistry, in Onuk you’d study “biophysics”. But don’t ask me how. I’m content that the Ancestor floated on the ancient non-existent sea and got us out of that valley of the stone giants.

As we floated slowly away, towards the distant south-western peaks at which I had aimed, I raised a hand in silent farewell to the goddess of Form 9c, Dallingdon Secondary School. I hoped she would continue to be happy where she was and who she was. The more I thought about it the more I realized I had done what would have been the right thing even without consideration of my companions’ needs. Justine’s human identity must gradually fade. The zitpoidl were physically immortal, or virtually so, but no mind can be immortal, for we all change so much, even in the course of a human lifetime, that (given long enough) new impressions must eventually over-write the last traces of a former personality. And for the zitpoidl there is more than enough time. So, as the ages pass, different personalities come and go, succeeding one another within the unchanging hides of the stone giants.

Justine will gradually change until she no longer bears any relation to what she was.

But I shall make sure that she is never forgotten.

>> Ixli