david lindsay: vast strangeness

by

antolin gibson

Confronted by the vast strangeness of David Lindsay’s writings, those giddy heights of fantasy, psychology, metaphysics, that seem to transcend the medium in which they are realized, the only thing a critic can do to start with is to find angles, to find some beam to hang his words, and then hope to scale the implications.

Here is one – The novels are landscapes and/or studies of the Feminine. As an angle, this has at least something going for it. Tormance, the world described so brilliantly in A Voyage to Arcturus, with its mesmerizing female inhabitants such as Joiwind, Oceaxe, Sullenbode, and clashing landscapes of ruggedness and voluptuousness, is on the level of inspiration at least – if not philosophical intent – a parable of male and female natures, culminating in the extraordinary story of Sullenbode, and Maskull’s unconscious betrayal of her.

The descriptions of Ifdawn and Matterplay, the male and female embodied in the very being of the earth, are the most wonderful in all of fantasy-literature, and the Tormance of A Voyage to Arcturus is a world for me as real as any that I have known.

Flying above Ifdawn: illustration by Joel Fletcher

Flying above Ifdawn: illustration by Joel FletcherThe female natures in The Haunted Woman, The Violet Apple, and Sphinx provide to a greater or lesser extent the motif of analysis that the author takes for all of life, which as well as being as it were organic, has a degree of formalism. The result is an ironic realism, as though the women are stripped bare and put under the glaring searchlight of the eternal dilemma of their natures. In Sphinx, this is carried to an extreme, which yet works: the main characters, all women (and superb studies) such as Celia, Lore, Evelyn, are bitter, restless, probing people – pathologically alive to the exploitiveness of their own situations upon them, and alive to the uniqueness of their own awareness of value beyond this exploitiveness.

Important to note that the nihilistic basis of A Voyage to Arcturus – revealed as the “Crystalman Grin” – is not seen by the grieving Maskull upon Sullenbode’s face, because of the tears and grime: true love, true emotion, triumphs. Also, while on the subject of the author’s own philosophy being thus subtly subverted by the author himself, is that Spadevil and Tydomin are just tired, simply that, but this is so movingly expressed, and I think the point about their killer, Maskull, is that he wants to get on, brimming with a life-force, towards some meaning, some value. Maskull holds the dying Tydomin in his arms – but then moves on. And this is Life – not an artificial literary technicality. Lindsay achieves the heartbeat of passion and calm, conflict and peace. A Voyage to Arcturus is truly driven by inchoate but purposeful vision which (despite the author’s own conclusions!) is a life-force unvanquished.

This force at the same time destroys – but also creates – the very bud and joy of spontaneity. Matterplay is the visual expression, but the heart of it is Maskull’s succession of rebirths, each one following some soul-shattering disillusionment.

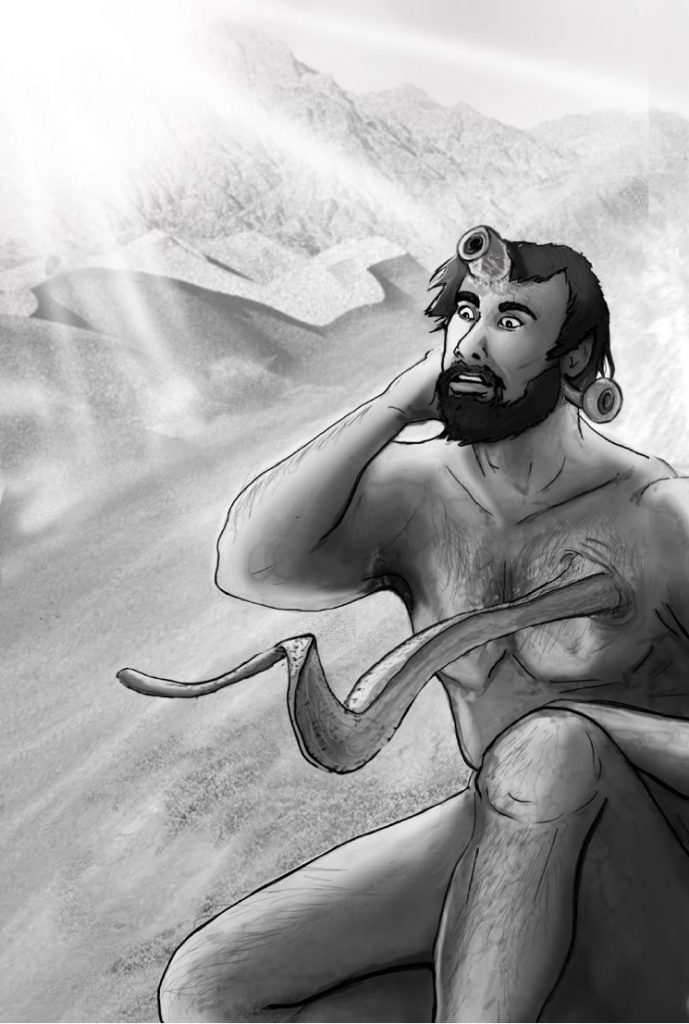

Maskull awakening on Tormance: illustration by Monica Burns

Maskull awakening on Tormance: illustration by Monica BurnsOn the world Tormance, one of the new body-organs has the effect of adding a new angle to vision, so that everything seen is deepened. The same can be said to be true of David Lindsay’s genius in all his writings: the addition of an angle, a further depth of experience, of philosophical implication.

In Sphinx this implication brims against a rigid carapace of manners. In other novels the carapace breaks down, by supernatural agency: The Haunted Woman, The Violet Apple, and most of all A Voyage to Arcturus. In these, there is a cyclical conflict, between the vast supernatural, and the vast confining of manners. The confining is often rendered as the vanquishment of vulgarity by a gnostic force. Sphinx is interesting because the carapace holds. It is a novel of balance, a novel of poise. But, precisely because of this holding, this balance, there is a quietus of devastation in the human relationships, an evenness and sameness of passionate emptiness. Surely only David Lindsay could have achieved such an impossible literary feat.

Why then does Colin Wilson – who recognized Lindsay’s genius – so persistently miss the point? Wilson’s contention, that Lindsay “could not express his deepest ideas in words”, is very depressing, because this is exactly what Lindsay does, perhaps more than any other writer of fantasy. And Wilson’s mockery of Lindsay’s style is a sad irrelevance, as it is the extraordinary style that is able to express such ideas, such targets that no other writer has managed to hit. This is, most obviously, true of A Voyage to Arcturus and The Haunted Woman – but consider the following in Sphinx –

She (Madam Brion) lifted her chin for an instant in an extraordinary silent laugh, which to her callers was like a descent into a clever wicked brain...

Chapter XIX

And this –

The mental vision repeatedly recurred to her [Evelyn] of great white

pillars supporting a Doric temple, which at the same time rotated on their axes

and revolved about the sides of the hall, in a gigantic, mystic dance . . . The

contrast between this uninvited fancy and the lonely, savage, melancholy

reality encompassing her – or perhaps it was their combination – so uplifted

her sensations that she kept pulling at the chain of her body. Strange beauty, inward and outward, flowed

together in a higher, still stranger beauty, exciting her to a degree of

rapture which was fearful to her physical frame, and which she was obliged to

suppress...

Chapter XX

Colin Wilson is good at sniffing out genius in the writers of fantasy but apparently incapable of embracing such genius in the joyous leaping way that it must be embraced if it is to be accepted in its entirety, or even remotely understood at all.

There is an idea expressed early in The Violet Apple of the inner sanctuary of the mind – a treatment by the author which treads deftly the path through sensitivities and conceits, to the “small truth” as defined in the novel. The starting-point of this idea is the secret garden of Anthony Kerr’s sisters. The analogy is with the mind of a poet and the conclusion is the most delicate touch, and suggestion, of the Unseen, which informs the uncertain and defenceless boundaries thus –

...there they tended and enjoyed their inconspicuous odoriferous flowers and herbs – cloves, pinks, marjoram, sweet William, musk, heliotrope, mignonette and lavender – and there, on summer days, looking away towards Ide Hill, far across the wooded cleft, they read their books, knitted silk and woollen garments, and dreamed, in voluptuous solitude. It was for them a world within a world, a retreat for repose and meditation. Neither a recreation ground for perspiring youth nor an exhibition gallery of prize blooms was, in their opinion, compatible with that poetic quietude, the mother of lovely fancies, which outweighed all other considerations. And in this obstinacy of a delicate inner nature they showed their relationship to Anthony, who also persisted in seeking the small, small truth...

Chapter 2

If both the technique of fantasy (intended often as the catalyst for a transcending awareness) and the natural representation of a life-experience, become as one, fused, and indivisible – then the trinity of fantasy, nature, and art are one, which is true of the psyche, of dreams, and the unconscious mind. Of this fusing, David Lindsay is a master – and this is partly because the symbols are so effortlessly achieved. In The Violet Apple the mythic apple-seed brings forth the pattern of romantic love that is etched deep in the inner life of the sufferers – for tormented, indeed, they are, and such indeed is the consequence of true love, its process through the reality of routine and of convention – the suffering of two souls that follows the arc of passion, to its level and flickering remnant of recollection. The arc, in many different ways, and at many different angles, is followed through in A Voyage to Arcturus and The Haunted Woman – and in The Violet Apple it is followed through to a single catalyst, the tasting of the mythic fruit, which comes late in the novel. This has the effect of a retrospective revelation of the actions, intimations, and frustrations of the protagonists. And the curious artistic result of the following-through to this fantasy-catalyst is a realistic, gritty, witty, searing story of romantic love, full of the pathos and elations, bathos and mis-happenings, that such – in reality – involves.

In truth, the mess of passion, as well as of beauty; the inevitability of mis-reaction.

But all around these psychologies and these landscapes of this world and other worlds, is the vast strangeness that only few writers have touched, and for me, of these, David Lindsay is perhaps the greatest of them all.

>> Authors