rider haggard:

style, set-piece and character

a study by

antolin gibson

Rider Haggard – one of the most type-cast of writers in literary history – is in fact one of the most unpredictable.

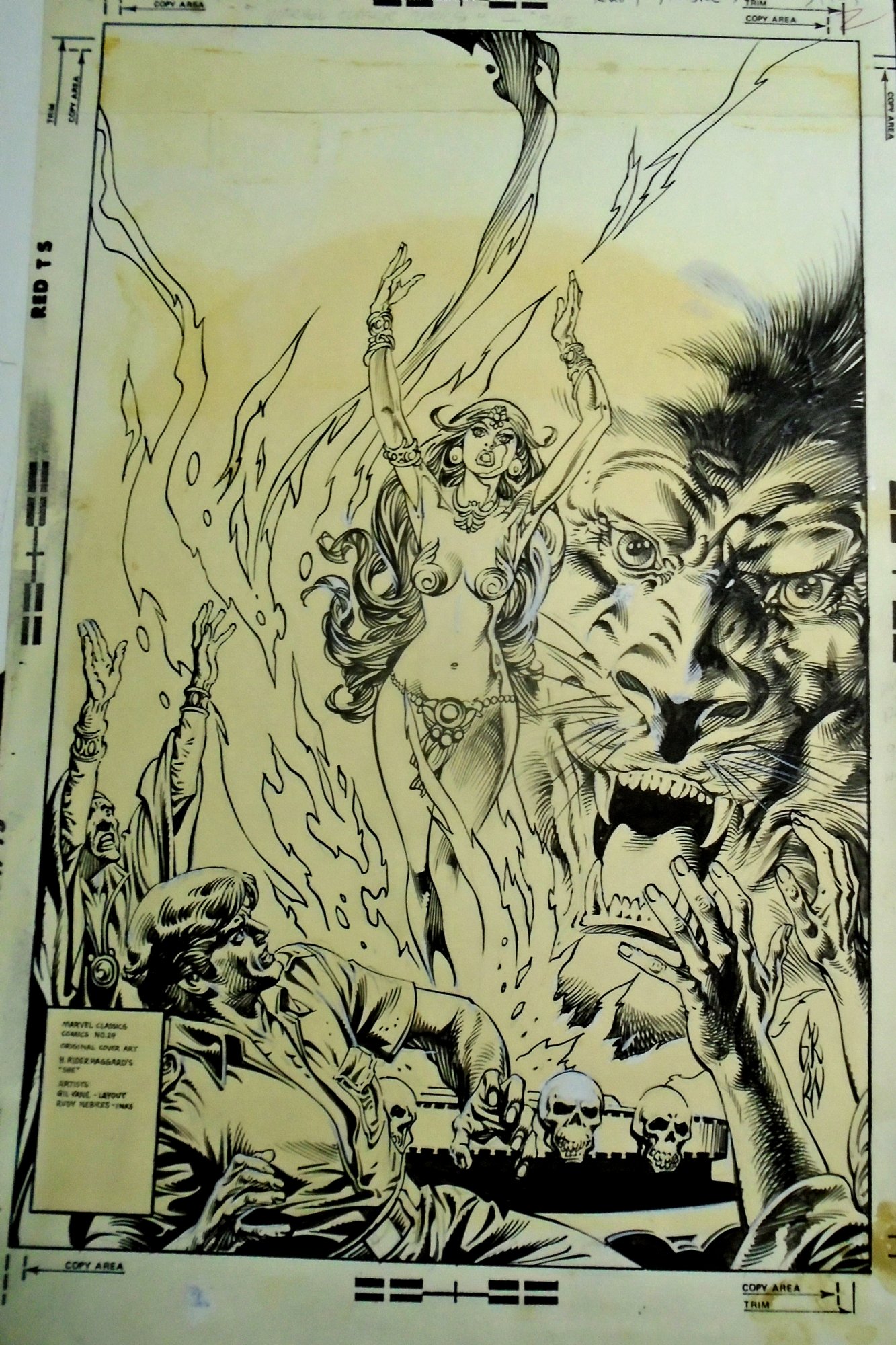

In the pace and flow and tone of his adventures, he has most in common perhaps with Edgar Rice Burroughs. But in the depth and variety of his characters, he is entirely on another level. The mechanics of the adventure yarn – perhaps most clearly and illustratively seen in King Solomon’s Mines – is washed over with archetypes, allegories, psychological insights and a bittersweet philosophy of adventure (something akin to John Buchan and Robert E. Howard) which almost, if not quite, call for a wholly new subgenre to be applied to Rider Haggard’s writings.

rebutting the objections to style

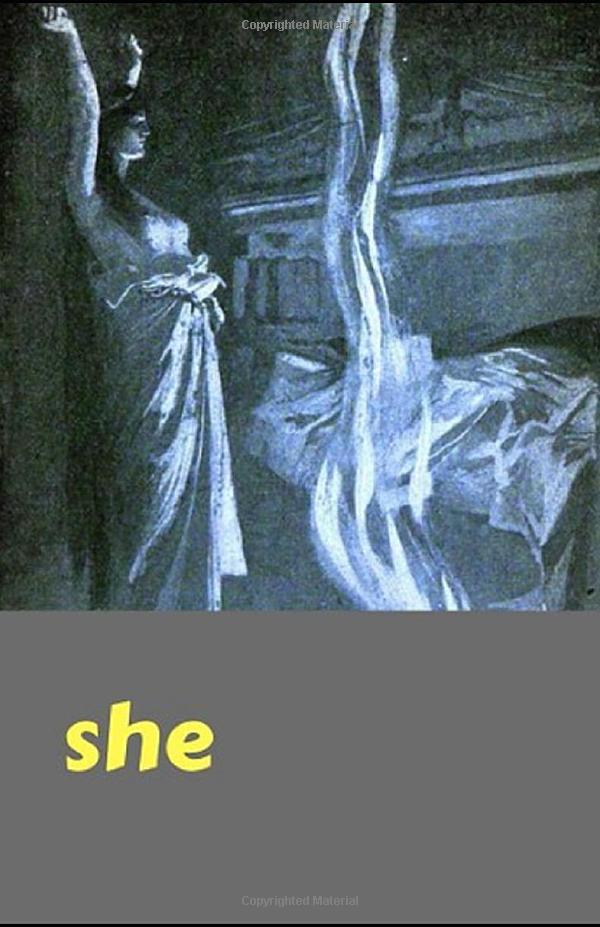

Many critics have pointed to what is seen as the paucity of his style – critics such as Robert Louis Stevenson, C.S. Lewis, Roger Lancelyn Green, although all these critics praise Haggard too. C.S. Lewis writes of She:

Two things deter us from regarding it as a quite satisfactory romance. One of them is the continuous poverty of the style, by which, of course, I do not mean any failure to conform to certain a priori rules, but rather a sloth or incompetence of writing whereby the author is content always with a vague approximation to the emotion, the reflection, or the image he intends, so that a certain smudging and banality is spread over all. The other is the shallowness and folly of the things put into the mouth of She herself and offered us for wisdom. That She, in her secular loneliness, should have become a sage, is very proper, and indeed essential to Haggard’s story, but Haggard has not himself the wisdom wherewith to supply her . . .

Essay “High and Low Brows” by C.S. Lewis.

As regards the point about the second “fault”, I think Lewis has missed the gigantic irony of Haggard’s intention. As regards the first “fault”, I can’t help feeling that the artistic virtue of a work of literature is achieved by the style that is employed: take a part of that style away, and the virtue goes. Something else might come, but not the overall achievement that has been valued, for what it is. A flaw can be essential to beauty. Would the beauty be as beautiful without the flaw? If flaw is style (bringing forth the analogy!), is it that style is therefore bad? The style essential in bringing forth the particular beauty – somehow detachable – whether it be drab, ornate, vague, or “smudging”?

Or, to put it differently, style is surely not an entity by itself but an integral part of an artistic whole; if the uniqueness of that artistic whole has worked out, then style – good, bad, or indifferent – must be lumped with the success because otherwise the unique result would be different, and not necessarily unique. Film stars who resort to plastic surgery to give perfection to their looks: take note.

The passage in She in which Ayesha is physically closest and most seductive to the lonely and physically misshapen Holly, could be said to be overblown in style, misguided in intention, shallow in execution – and yet, it works, and is in a sense a microcosm of the book as a whole and very typical of Haggard’s writing:-

And without more ado she stood up and shook the white wrappings from her, and came forth shining and splendid like some glittering snake when it has cast its slough, ay, and fixed its wonderful eyes upon me – more deadly than any Basilisk’s – and pierced me through and through with their beauty, and sent her light laugh ringing down the air like chimes of silver bells.

A new mood was on her, and the colour of her fathomless mind had changed beneath it. It was no longer torture-torn and hateful, as I had seen it when she was cursing her dead rival by the leaping flames, no longer icily terrible as in the judgement-hall; no longer rich, and sombre, and splendid, like to a Tyrian cloth, as in the dwellings of the dead. No, her mood now was that of Aphrodite triumphing . . .

’So, my Holly, sit there where thou canst see me. It is by thine own wish, remember – again I say, blame me not if thou doest wear away thy little span with such a sick pain at the heart, that thou wouldst fain have died before ever thy curious eyes were set upon me. There, sit so, and tell me, for in truth now I desire praises – tell me, am I not beautiful?’

She Chapter XVII

imperatives of adventure

To me, a large part of the success of the romance is due to the huge irony of the relationship between the singularly ugly Holly and the singularly beautiful Ayesha. And indeed, there is a SINGULARITY of invention and treatment, which I find moving and itself beautiful.

But it seems to be the case that writers of adventure-yarns tend to be weighted down by the mindset of their own times, and doubtless this is because style and pace are stretched to a certain key or pitch. Such yarns, after all, cannot be written as meditation. Thus, the “stretch” in John Buchan includes formulae or fillers of his time, Haggard’s of his, Scott’s of his, and so on. On one level, the writer reverts to presumption and pronouncement, in order – on another level – to hurtle forwards. Some supreme craftsmen succeed in making scarce sacrifice to the yarn’s imperative, however. Thus R.L. Stevenson throughout his adventures weaves archetypes of description and character, so that it can be said that the author’s adventures – such as Treasure Island and Kidnapped – and his meditations – such as Doctor Jekyll and Mr Hyde and The Weir of Hermiston – appear alike on the same level of universality. And although Rider Haggard is not in this class of greatness, his status is very difficult to measure.

The pure adventure-romance, at its best, possesses a quality and genius undervalued by critics. With other kinds of story, it is legitimate (and relatively easy) to use such criteria as character-depth, perceptiveness in social or historical analysis, points of style, humour, horror, irony, etc.

But, in the adventure-romance, the secrets of success become elusive. It is tempting to use words such as “rip-roaring”, “full-tilt, “fast pace”, “galloping” or simply “ripping”! But what makes the “ripping”?!?

Of course, in a really good adventure-romance, there must be good characters. There can also be irony, such as in Edgar Rice Burroughs’ excellent Carson of Venus. Historical perceptiveness, certainly – John Buchan’s The Blanket of the Dark, which is almost as good an historical novel as it is an adventure-romance.

But, still, that elusive quality, not so much the pace, as whatever it is that makes the pace work . . . In this connection, King Solomon’s Mines is a very good work to study. For one thing, there is a lot wrong with it. Without tediously espousing a by now way-worn political correctness, it is beyond doubt that the pervading attitude towards Foulata is exceedingly irritating, the – yes – sexism and the – yes – racism – culminating in Quartermain’s reflection that it was perhaps just as well she had been killed, as her relationship with Captain Good would inevitably become an embarrassment!

set-pieces and characters well-set

And yet, Foulata is a very well portrayed character, vivid and moving and entirely believable. Also, cutting across the stilted rhetoric of attitudinal “isms”, there is a fresh flowing sympathy towards her from the author’s own pen, which comes from the deeper unhampered region of the author’s heart.

I think it is this flowing, this depth, which is beyond any philosophy put in words; but hinting at something larger than confined societies and prejudices, that serves to link together the great set-pieces of the adventure, the travel through the desert, the burial alive in the Mines – the author’s descriptive genius in these scenes would not be sufficient in itself to make the book great, if it wasn’t for the flowing-in-between-and-through, the almost intangible sympathy, the freshness and wildness (and gentleness) of tone, rather than style. As for the virtuoso set-piece, such as Ayesha’s escape from Sidon . . . the crossing of the storm-buffeted ridge to the Cave of Fire in Kor . . . the death of Philo in Ayesha’s arms . . .so good is Ridger Haggard at the set-piece that it is logical – but wrong – to think of him as a writer par excellence of such culminations interspersed with awkward “fillers” which these days would be termed politically incorrect anyhow.

But the set-pieces are part of an organic, aesthetic, even to some extent philosophical whole. The duality in Wisdom’s Daughter of the spiritual and the profane, set out at the very start with the vision of the meeting between Isis and Aphrodite, is a theme one feels at the author’s heart, and a duality which reflected a struggle in the author’s life. And this goes for the symbolism in many of the other grand set-pieces – the theatre, as it were – in Haggard’s yarns. In Morning Star there is a wonderful – and partly slapstick – example of his mastery in this regard, in Chapter V, “How Rames fought the Prince of Kesh”. All the characters and their responses, during the ill-fated feast of Pharaoh, are exceptionally well staged. Count Rames’ life is forfeit, after his killing of the drunken Prince Amathel. But Rames’ beloved – the Morning Star of Amen, Tua – has a plan. The mother of Rames, Asti, says to her: “Your Majesty has done strange things tonight.”

“Very strange, Nurse. You see, the gods and that troublesome son of yours and Pharaoh’s sudden sickness threw the strings of Fate into my hand, and – I pulled them. I always had a fancy for the pulling of strings, but the chance never came my way before.”

Shades of Ayesha here?

The passage where Tua and Rames suddenly drop their structured roles of statecraft and soldiering to embrace passionately (and hopelessly) as lovers is very moving. Rider Haggard is just so good at this kind of thing! I wonder . . . why have critics, and great critics, overlooked this wonderful aspect? Is it possible that it is because the adventure-romance is assumed to be inferior in the department of character? That of Ayesha, her relationship with the wise Noote, her teacher; her infatuation with Kallikrates, and jealousy of Ammanatas, does evolve superbly: Rider Haggard is so very good at character, a fact which in itself gives soul and depth to the adventure-romance.

Ayesha is a wonderful creation just because (pace C.S. Lewis) she is a feisty lass: one alternately wants to give her a good hiding, and . . . well, worship “She Who Must Be Obeyed” – although the later title is not yet official in the narrative of Wisdom’s Daughter. And is this not superbly ironic – “Wisdom’s Daughter” – living through the ages and not growing a jot more wise – just as civilization itself, just as humanity itself, through the ages – and just as stupid, just as great? True to life! She is a character one can visualise wonderfully well, thanks to the author’s skill and zest – and, actually, which is not over common in writers of his generation, this very masculine author is perceptive and sensitive in portrayals of women. Foulata – as well as Ayesha - comes fully rounded and conceived to our minds.

There is a paragraph in She and Allan which points clearly and eloquently to the reason why Allan Quartermain is such an impressive study of heroism, really more so than most other examples of the swashbuckling type, certainly more than John Carter of Mars:-

But then it was that I made one of my many mistakes in life. Most of us do more foolish things than wise ones and sometimes I think that in spite of a certain reputation for caution and far-sightedness, I am exceptionally cursed in this respect; indeed when I look back upon my past, I can scarcely see the scanty flowers of wisdom that decorate its path because of the fat, ugly trees of error by which it is overshadowed . . .

She and Allan Chapter IX “The Swamp”

Throughout this chapter especially – and through the book as a whole – there are insights into the hero’s egotism and balance, almost as though the two were struggling inside him in a grim, tragic harmony, rather as they did in the life of Rider Haggard himself, and other writers of the Imperial Stamp, such as Rudyard Kipling and Conan Doyle.

As is often the case in Rider Haggard’s tales, secondary characters achieve a very primary significance – the alcoholic Robertson in She and Allan, and his mourning for his wives and illegitimate children, and his passage to redemption, strikes the true tragic and heroic note.

And it is this note indeed that continues subtly and grandly and with very great variety through the works of this often misunderstood and underrated writer.

>> Authors