the slavanns must play

by

robert gibson

During the Plutonian Occupation of Earth, a lad of fifteen is given an errand to run. These are his thoughts on that day.

From the undulant curtain, visible out of the corner of my eye, comes the latest repetition of the summons.

"Your grandfather wants to see you, Slavann Edwin."

The husky croak is that of my "Cousin Ralph".

Whoa - wait a sec. Who am I to put inverted commas around a fellow creature? I'll answer him politely, though I shan't look at him directly. "Fine by me," I say. "I'll be along soon."

I don't address him as slavann, though the word is ubiquitous nowadays, like particles of soot in a polluted atmosphere. Actually, although it's such common currency, I suddenly find myself stopping to wonder what it precisely means. I'm normally good at words. I've scavenged heaps of books and I have lots of time to read them, pumping myriads of little bubbles of perception to alleviate the dull, treacly mind of one who must live in a conquered world. In fact in many ways I may have given myself a better education than I would have had at school during these past four years. Who knows? But as for slavann... well, all the reading I've done will not help me at all. A new word for "slave" would seem unnecessary, so perhaps it means, more exactly, "slave-by-nature"...

Enough of that. Must concentrate. It really is time I went to see Grandpa. I've run out of other things to do; my den is packed with stuff, and I've metaphorically "cleared my desk" for the time being.

Really the only thing that makes me hesitate, is a dopey sort of instinctive reluctance to play what looks like the last little pleasurable card in my hand. It's going to be good to talk to my last proper relative. Boy, is that guy lucky! What used to be a terrible disability is now something enviable. Perhaps contentment is contagious, in which case I may get to enjoy some of it without paying the score...

I finally make a move. I exit my room and, ignoring the swirlings of the flatties who close in behind me, stalk in blinkered fashion through the passage towards the old reception hall of the apartment block. A door has been added to the end of the passage, but it's invitingly open.

The voice quavers through the doorway, "Come in... come in, Edwin, if it's you! Yes, it's you; I can tell by your step... Come in, lad. We're the only ones left down here. We need to make plans."

Meanwhile a thinner voice at my back, no louder than a whisper, urges me on. "Go ahead. But don't crowd him," it whines. "Remember, he's blind. And don't go quizzing him with your silly questions."

I mutter in reply, "I'm not like that any more, Aunt Denise." And that's true enough! Nowadays I just accept things. It's the way to be. Accept the hissy voices, and imagine their owners as people, hidden behind the curtains. Careful not to look over my shoulder, I add: "I'll do as you say." Then, as ever doing my best to ignore the sliding motion behind me, I walk into the big room, the ground floor's reception area, from which several interior doors lead to other sections of the apartment-block.

"Here I am, Grandpa. It's good to see you."

It does indeed lift one's heart to see the old feller settled on his rocker, surrounded by his adjustable overbed tables with their heaps of food-tins, tin-openers and bottles of drink, all in the middle of the largest floor-space in the entire building. No reason why he shouldn't survive for weeks. Especially with stacks of books in Braille to occupy his mind and keep up his spirits. To cap it all, within easy reach he also has an A3 sketch-pad and black marker for his pathetic blind doodles, and though such a hobby makes no sense to me, I accept - everything.

Grandpa chuckles, "You took your time, but you've been busy, I dare say, building up your own hoard. Anyhow, nice of you to pop over at last. Not so good as when I could see you likewise - but never mind the useless past..."

"Hey!" I protest. "Please don't call it useless... It's - um - "

"You were about to say, it's all I've got?"

I'm glad he can't see my embarrassed face. I fortunately have enough wit to swivel the conversation: "What I really mean is, you're all I've got: and so I need your memories, your achievements, to count for something."

"Ah." He rocks back and stares sightlessly at the ceiling. "It's not quite true, that I'm all you've got. You also have your own estimable simplicity of mind. Hang onto that, lad. As for the past - You know what I did for a living, in the old days?"

I venture, from a scrap of memory, "Sman...Tiss...Ist."

He jerks his head sharply. Quick as a flash he demands to know:

"And do you get what a semanticist is, boy?"

"Nah," I shrug. "Or at least... nah. I once overheard... it's something to do with what stuff means. What words mean."

"Hmm." His shoulders slump and he starts to ramble, "All that stuff's no good now... In fact, that's what did for us - too much thinking, while They were slicing their way here."

"Slicing?" I echo.

He thumps his fist. "Here's a case in point! It's a word, and it does the work! But in the old days we'd have wasted time chewing at terminology, even if we'd known what we know now - that the lower dimensions are the greater - which we ought to have guessed, from our own obsessions with unified field theories and the idea that

simplicity is best - ah, never mind, what's the use! We'll never get the chance to make that sort of mistake again. No news any more, no good investigating anything whatsoever, except..." and his voice gets hoarser, "just one thing I very much want to know. Are some of Them in this actual building?"

I'm unreasonably surprised. Blind though he is, does he really not know? I could answer his question without a doubt - but rather than spoil his hopeful uncertainty, I enter into the spirit of it.

"I haven't spotted a single one," I say, and strictly speaking my words are not a lie - if they refer to the originals.

"But we humans keep to the ground floor, don't we?" he points out.

"Yes," I admit.

"And it's the upper floors they like, eh?"

"But, you can't see those parts from down here," I remind him. I don't think he's being much help. Can't he sense that I'm doing my best to encourage the kind of picture he wants? "You'd have to - er - glance up the stairwell. No other way to determine whether our building has been, uh, infested."

"Might you scout a bit?" he gently asks.

"Me?" I say. I'm stupidly about to object, But I already know! Missing the point, that he does not know.

"Scout a bit," he repeats, "just to ascertain the truth about our block?"

"Um..."

"Oh, don't get me wrong: I wouldn't send you into danger. Not more danger, anyhow, than we are already in. Besides, they'll see to it..." he trails off.

Since it's no use expecting him to read the puzzlement on my face, I must ask aloud: "What do you mean, Grandpa? They'll see to what?"

"They'll see to it that you become too terrified to get close."

"Oh, great," I say dryly.

"It's just their way, you know; just their process. Won't be pleasant... but, if you can endure, you may get back here with some information."

The thought steals upon me, that it won't be any use saying no, because I'd regret it as much as if I said yes. Nevertheless, weakly playing for time, I say: "Can you - is there anything you can tell me, about Them? About the background, to, um, make it easier?"

He lets out a bitter laugh. "That's going back a long way. You know why Earth got beat? Can you guess?"

"They were too advanced for us," I shrug. (What else?)

"Not so much that, no. Rather than They being advanced, it was we who were retarded. That's to say: stupid. Our great vice, the thing that held us back, was.... incredulity. First we couldn't believe in the existence of the Thiddin Snewn. The idea of intelligent beings slithering about on nitrogen glaciers, was too fantastic. Then, after we had detected them for sure, we still couldn't believe that they'd be any threat to Earth. Our assumption was that this world would have no value for them because they couldn't live here. Well, we now know how much use that line of reasoning was! Our governments and military - utter fools, blinder than I am, for all their expensive eyes! The fact is, two-dimensional beings can live anywhere. In truth the Thiddin Snewn particularly like Earth because of our planet's bonanza of millions of geometric buildings, its wealth of smooth ceilings!"

Grandpa's speech, risen almost to a shriek of frustration, yet has a calming effect on me. It makes me less scared when I think of big things. Earth; Pluto; war between worlds. Great stuff like that, a wash of dreamlike hugeness, for a minute or two unclogging our local, suffocated existence.

Grandpa, perhaps, feels relief too; his voice subsides into almost a drawl, as he goes on to remark that it has been a war without hatreds. The enemy has taken Earth almost bloodlessly, and most people apparently have gone over to Them; which is a fact too numbing for hatred. How it happened, is not clear. You have to take part in the process, apparently, in order to understand it, and of course in such a case it's best not to understand.

"Hey," I say, "I've thought of a cute way of looking at it. If I go look at the stairwell, won't I - maybe - count as a scout in the war?"

Grandpa nods, with a smile. "You go ahead and put it that way, Edwin. I'd go myself, even if I had to go on crutches. Only, I'd be no use when I got there. Now, see this pad?"

Dramatically, with both arms, he holds up the sketch-pad high, and flicks the pages. Puzzled and curious, I approach and, as he holds it out to me, I take the object from his hands.

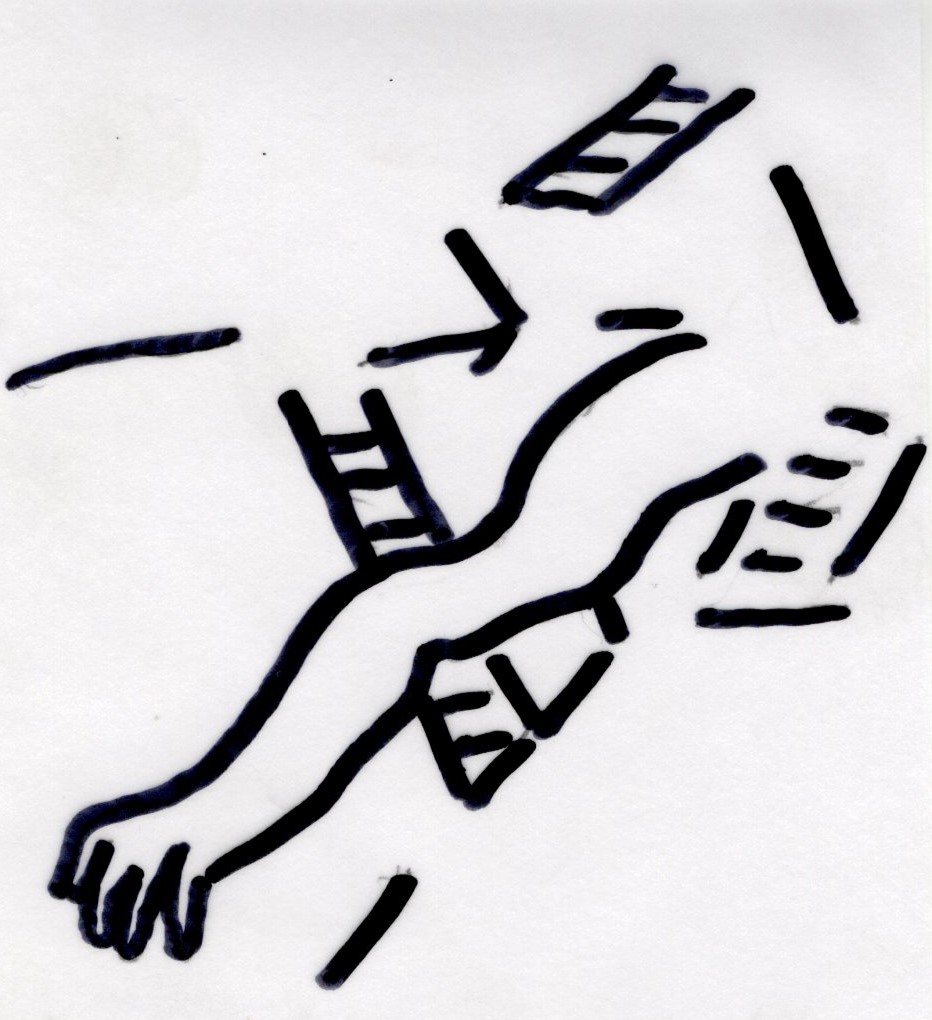

I leaf through it. Despite his blindness, Grandpa has drawn designs on page after page. With an imagination strong and disciplined, he must see with the inner eye. Well, it's a trick anyone can learn, like writing in the dark; but he's especially good. As to what the diagrams are: whatever they mean and whatever purpose they have, they look professional. Blocks and connecting lines which, though they don't make sense to me, yet remind me of other diagrammatic stuff... of Beck's London Underground map, or of cubist renderings of the human face and form. Grandpa, evidently, is in the simplifying business, his aim being to reduce reality to a more basic arrangement of straighter lines and fewer angles.

I ask, "I'm supposed to take this with me?"

"And show it to Them, if events turn out that way. Let's get it over with, eh? Good luck, Edwin."

Silence falls and I realize that the conversation is over.

I could try to start it again; but instead I turn to go. He's right. Best get the business over.

I don't look back. Anticipating, I envisage the rooms I must go through in order to reach the stairwell. Including the rooms created by recent partition the total should be four. Of course, if it hadn't been blocked off, the stairwell would be accessible from this old reception area. As things are, I must go a roundabout way. Not very long, though. At a run, I could go through each of the four interconnecting rooms in a few seconds. But of course I don't run; I pad along cautiously - though I dare say I'll take it faster on the way back.

I approach my route's first doorway, and go through into a deserted room, which has been abandoned untidily by its occupants. The exodus occurred, probably, in the panic of the early days, but I don't think about that big stuff now. Instead, it's back to thinking small, back to a shrunken way of feeling. The brief ideas of interplanetary war and the fate of the Earth, which Grandpa had sparked in my mind, have faded and left me in the constricted every-hour reality populated by concerns such as, how best to creep from room to room. Living thus in the moment, I retain, at most, some short-range vision fore and aft to adjacent moments.

Second door. Into the next room. This one's more nearly empty than the last one. I expect the next one will be barer still.

I'm actually feeling surprisingly good. I suppose it's the result of having been given something to do. A pinch of significance helps season the hour. Not that I'm actually happy at the prospect of my destination. But it seems reasonably certain that I am not going to chicken out. I possess a sheaf of positive attitudes, although I expect that, like arrows in a quiver, each of them can only be notched and fired once. One of them which won't last is "live in the moment, value the moment" - that's to say, the enjoyment I feel at not being there yet. I'll need a replacement attitude handy when I do get there. Like for instance the innocent question, "What can possibly be wrong with just having a little look up the stairwell? It surely can't do any harm just to look at what may have spread through the upper levels."

Third room. I begin to hear a voice.

Not in my ears but in my brain, the murmur:

We - are

the Thiddin Snewn.

Flutter - flap - swirl.

The Thiddin Snewn.

I have no gun to reach for. Instead I unlimber Grandpa's sheaf of sketches and prepare to hold it up. No weapon, but it might act as some sort of safe-conduct. I hope. In nightmare there are no heroes.

We are

the Thiddin Snewn;

flutter flutter flutter,

the Thiddin Snewn.

The inanity of it grates on my nerves, withers my soul, but it does not amount to an excuse to flee. I hope the excuse comes in time, though. Dismayed at my funk, I glance at page one of the sketch pad, in the hope that there might be something in it that could infuse some pluck into me.

Grandpa has written one phrase and one only. It is the only actual writing in the pad.

"Central Colding System."

Any moment I'm going to start believing stuff which so far I have not been able to believe. That imminent awareness is hard to bear. Here is the last door. I see no bolt on it, but I'm relieved - as I look back - to see that at any rate there's a bolt on the previous door: vaguely I suppose that it might help my retreat, if need be.

And now -

Through the fourth door, I find myself in the stairwell at last.

Plenty of daylight here: the windows are large all the way up in this concrete and glass apartment block. Craning my neck I see, on the receding perspectives of higher ceilings, the region where They reign indisputably, in the form of hundreds of fluttering streamers, like an excess of dull grey faded Christmas decorations.

Trite in one way, nauseous in another, it's a manageable sight, if one is careful. Almost it's a consolation that the Thiddin Snewn are so different from anything we would normally think of as intelligent beings. "Being as different as that," the reassurance goes, "those weird flutterers can't possibly have anything to do with me, and so, even if they were to stretch towards me, to reach down for me, I expect I could keep from panic."

Thus, not yet am I terrified. But time seems slowed, and my will seems fossilized; I must wriggle out of such paralysis - must not waste these moments, must display what I've brought, make my offer while circumstances allow.

I induce my muscles to move. Up goes the sketch-pad as I hold it out to them, flicking its pages - and while doing this I try to answer their mind-words with my own inane mental chant:

Propitiate

the Thiddin Snewn.

Central Heating Central Colding

Quite the same.

And what's this? The worst! The worst! I saw what I saw, and now I'm running, I'm stumbling. No time and no need to look back; pointless to confirm with any second glance, that the, er, occurrence occurred. I tear back through that room which contains the far door with the bolt on it. I lunge for that bolt and tug at it, meanwhile imagining what could be close behind me.

For at the instant that those streamers grew rounded, fleshing out, they necessarily inflated, magnifying their reach down in my direction -

I try to blank that picture while I concentrate upon wrenching at the cursed rusty bolt, madly imploring it to move. But the persistent recall, that refuses to be blanked, of the sight I have just seen, the streamers acquiring human contours, ballooning out into arms and legs, albeit with extra-many joints to dangle crinklily... diverts my mind to wonder, are They mere yards behind me now? Mere inches, even? I could settle the issue by looking over my shoulder. No, oh no. Fight that bolt -

And then I hear the voice in me.

Fumble fumble fumble

in the light of day.

Fumble swirl flap

the Slavanns must play.

Terror and grief bring extra comprehension: we'd heard them so often call us the Slavanns, but we'd assumed they were slavers calling us slaves; but no, Slavanns is a generic term for both them and us; it's for all, equal participants in what must be. "Play", then, means "co-operate" - for we're all engulfed - and central heating central colding ARE the same -

NO! I'm not yet classifiable as identical with the Thiddin Snewn! And furthermore I'm not idiot enough to spend one second longer fumbling with this bolt! Because, you dope (I tell myself), even if you could get it to fasten, you'd still be on the wrong side of the door!

Shock. Amazement. Confusion. What excuse could there possibly be for

such a "senior moment" on the part of a fifteen-year-old? Or is it some

traitor within me, that wishes to wait here meekly for the fingers of the Thiddin

Snewn to flex at my collar? Suppose I still have an instant in

which to tear through the door and close it behind me (not bolt it, for

there is no such mechanism on its other side) and go on through the

next room: I had better use that moment, had I not? I do, I do. I'm sane again.

Swirl flap flap

The Thiddin-Snewn.

Coming after you

The Thiddin Snewn.

Ignoring the mind-voice as best I can, I stagger from room to room, exhausted by the cross-buffets of experience, but at least understanding how right, rational, sensible it had been to flee. Utterly coherent is my awareness of the scale from bad to worse: of the significance of the change, when the ordinary plain horror of those thin weird streamers which I saw at first had suddenly sprung forth into the closer nightmare, the far worse, identity-threatening shapes which they then took on. At any rate I hope and pray that it was an action of theirs. Otherwise - here's the great fear - it may be I who am adapting to see them thus: endowing their flatness with an aura of 3-D flesh, implying parity with my own structure, which would suggest that I am going the way of so many other flatties... Oh, well, let's hope it was a "flash in the pan", and running has dowsed it.

I'll know very soon now.

The voice, thank goodness, has faded.

Now to round the last corner, and back to the door through which I set out.

I see a curtain has now moved across that door.

I said, didn't I - a while back - that I'd leave out the inverted commas? Call a spade a spade, call a relative a relative.

The curtain is slow to move aside, even though I approach with obvious intent to pass through. It's a horrid enough sight, with its undulating, lackadaisical billowing, displaying an imprinted face with fixed grin and sparkling eyes, but for the first time I can look at it squarely, while drawing a deep, easy breath. It flinches, surprised at my bold approach, and I make allowances for that - I can afford to be tolerant: for how infinitely worse would the encounter have been for me, how dire the implication, if I had become adapted to see this 2-D monster as re-rounded, fleshed back to equal my humanity! Whereas as things are, the differential is preserved.

Well, no time for shilly-shallying. Must go in and make my report to Grandpa.

Firmly I say, "Swirl aside, Aunt Denise."

FINIS

For the Roll Off a Tangent podcast on this tale see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FxVkK5KMP3Q&t=18s.

Note that it begins a bit raucously with me trying to satirise some modern slang... not knowing that the recording had started.