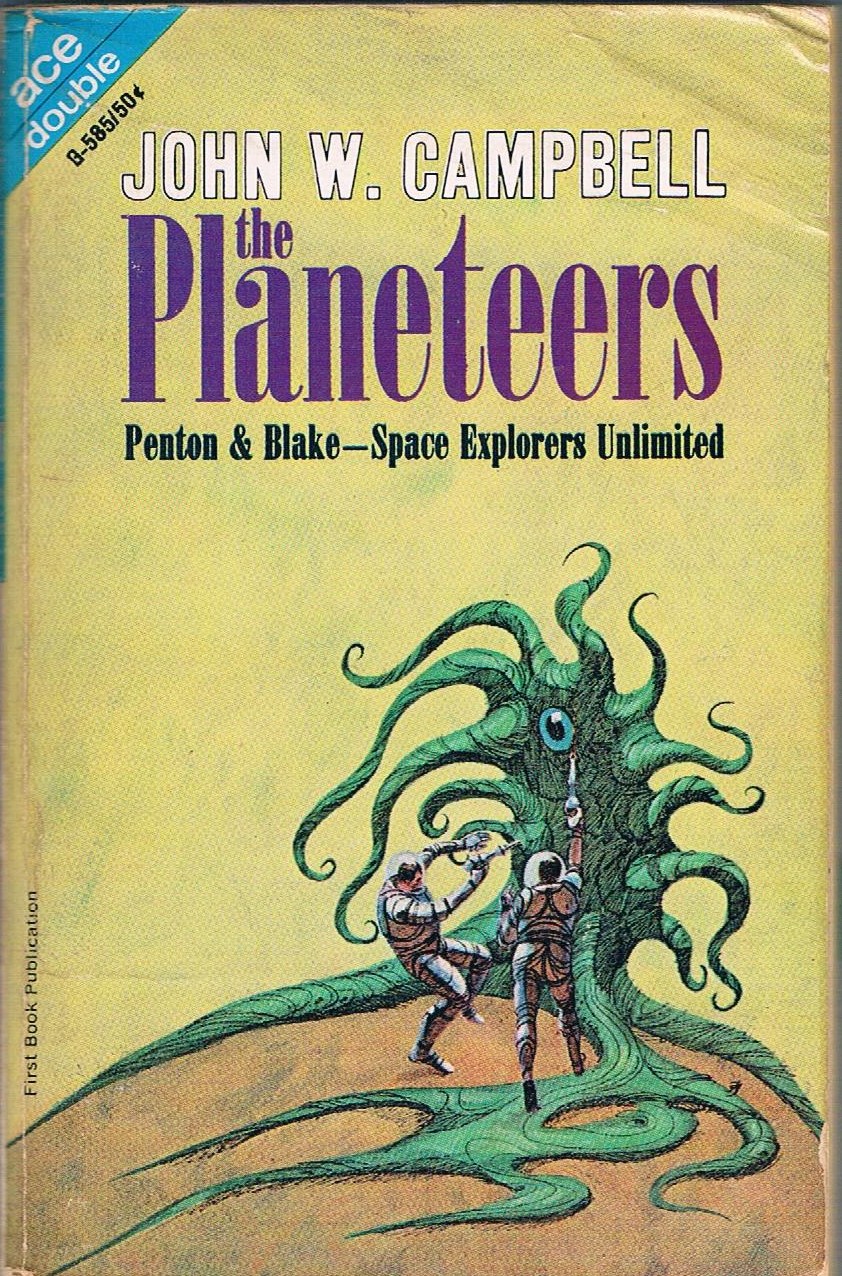

pioneering fugutives:

John W Campbell's

Penton and Blake

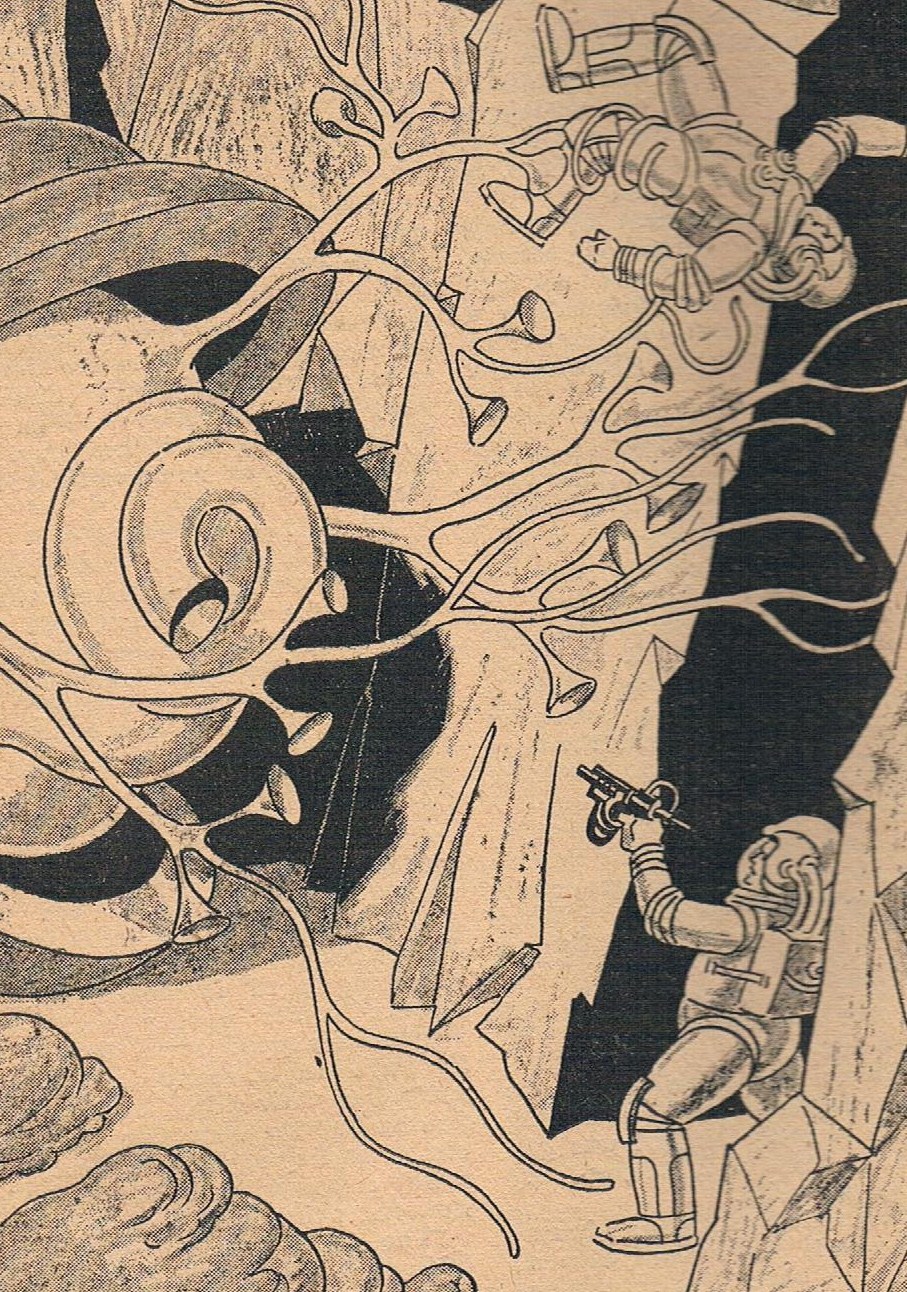

Imagine you were the first space-pilot, and you had the run of the Old Solar System! How you'd be the envy of fandom! The heroes of these Golden Age tales, Ted Penton and Rod Blake, who had to leave Earth rather fast in their new atom-powered spaceship because they had to make themselves scarce until the uproar over early misuse of atomic power died down - they had a chance that comes only once in the history of the OSS and of mankind. The inhabited Solar System, endlessly varied and colourful, was theirs to see and to explore.

Harlei: Stick to your guns, Zendexor - I can tell that Stid is getting ready to utter a grumble. You'll have to let him have his negative say, and I can guess what it is. Just don't let him put the readers off -

Stid: I don't put readers off for fun. I have a positive aim in view. I want us to beware of (in trade-unionist terms) "eroding the differentials" between clunky writers like Campbell and far better writers who deserve more space. By giving Penton and Blake an entire page, Zendexor, aren't you implying some parity of worth between these stories and (say) those of Gallun or Weinbaum or Clark Ashton Smith, all of whom could write rings round the likes of Campbell in the "first voyage to a world" department? It's those greater writers I'm thinking of. Because I value them -

Zendexor: Wait, Stid, I fear you're leading us up a blind alley here. You're making a huge, unwarranted assumption - namely, that I allocate space according to comparative literary merit. I don't! If I did, then seventy per cent of the site would be about C S Lewis.

Stid: It's not just literary skill I'm talking about, but imaginative richness too.

Zendexor: Even so - the making of comparisons between writers is not how the reading experience works! When we read something, we aren't holding different authors in our minds at the same time - we are concentrating solely upon the book in our hands. At least, that's true for me. Certainly I would run out of stuff to read if I were always judging tales in the light of the achievements of a few literary supermen.

In reality, our faculties of appreciation adjust as we move from writer to writer, analogously to the dark-adaptation of the human eye under conditions of varying illumination. That way, dimmer writers' virtues get a chance to be seen. So get those pupils of your inner eye to expand, sphincter-like, to fit the style of John W Campbell and we'll see how we get on with the tales of Penton and Blake.

on ganymede - obscurely on the run

As they headed toward the city, traffic became heavier, and Blake anxiously watched the system, trying to learn the rules of the road. They drove on the left, moving at a lively clip.

"They have traffic lights," said Penton quietly. "I just spotted the damn things. It's a block system, like New York's. See - way up ahead you can see that yellow light. That's stop. Red is go. We'll have to stop at this next block."

But traffic became heavier. Lights became confusing. And suddenly a bright flush crept over the sky, and almost immediately Jupiter loomed on the skyline. Five blocks later they were hopelessly caught in a traffic jam in the heart of the city. Drivers near them looked - and left. Beside them they had seen, driving a car, two monstrous, squat beings, with great ropes and bundles of inhuman muscles. To them they appeared like horrible animals incredibly become intelligent.

Blake opened his door.

"All off here. Transfer. Last stop. We can't drive through those stalled cars, and somehow I don't think the drivers are coming back." Penton got out the other side, and silently they walked up the line of traffic. Behind them doors opened hastily, and feet scuttled away...

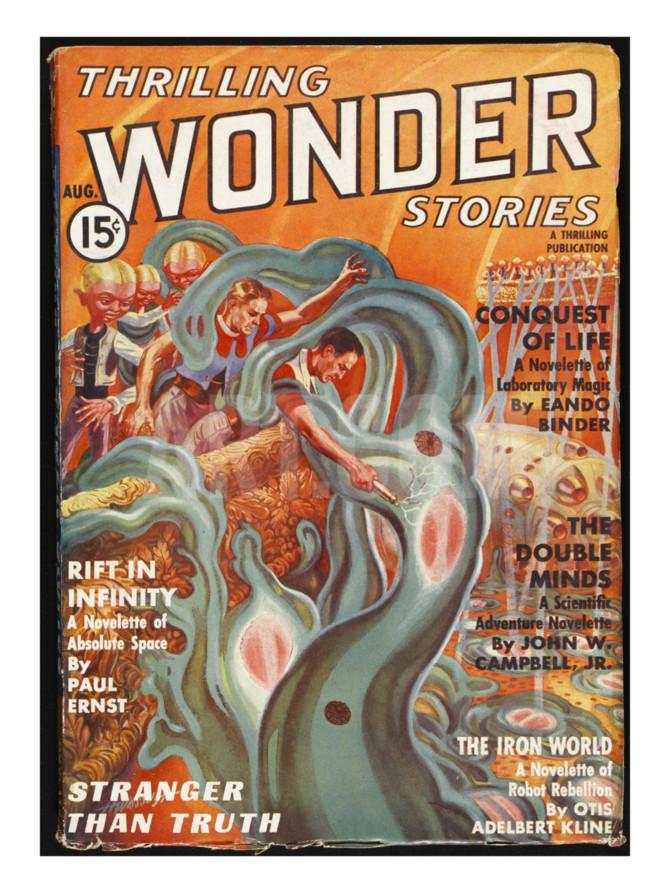

- The Double Minds

Stid: What made you choose that particular passage, Zendexor? Are you secretly on my side, trying to prove my point for me, that this writer clunks?

Zendexor: I intend to pose as arbitrator between you and Harlei. As usual.

First let's all admit that one can level a charge of incompetence against this text, on the grounds of obscurity of meaning. The sentence "Drivers near them looked - and left" is supposed to mean that Ganymedean members of the public were scared by the appearance of the Earthmen. But it doesn't do that job clearly enough. Only some lines later do we get the message clearly confirmed: Behind them doors opened hastily, and feet scuttled away... These tales are full of such jerkily mis-timed indications, and for that reason most of all I have found them not easy reading. (To my mind the hardest of them is The Immortality Seekers, set on Callisto.)

Another negative criticism is that the bantering style of Penton and Blake's conversation is unsuited to the mood of wonder and awed discovery which we expect from the first trip to another world. P and B are real down-to-earth types, severely practical, with no poetry in their souls, it has to be admitted.

So perhaps I did choose this passage as one that typifies the P&B series' faults.

But now, ladies and gentlemen of the jury, we are going to hear the speech for the defence.

on ganymede - cities and races

To start with, ask yourself: how many writers even try to give us an urban native civilization on Ganymede? I can't think of a single example, except this one. So at least a gap in the literature is being filled, to some extent.

Moreover, the picture we get of Ganymedean society has some subtle aspects.

We're given not one but two races of intelligent Ganymedeans, the Lanoor and their oppressors the Shaloor. The Shaloor's "double minds" give them advantages and disadvantages. Penton and Blake make use of the latter to help the Lanoor throw off the Shaloorian yoke...

Stid: Maybe at this point you'd better mention that one of the factors underpinning the power of the Shaloor was a kind of biological construct which seems markedly un-original: an amoeboid monster that can change its shape and whose name starts with "sh".

"...The Shaloor conquered the Lanoor rulers originally by sending shleath up a small drain pipe in the form of a thread of protoplasm, and having it assume the form of a roller in the barred and defended fortress where the Lanoor rulers were. The shleath digest anything the Shaloor want them to. They can dissolve even metal. Only glass is impervious to them. If there is even a ventilation hole, the shleath can seep through."

"How many are there?"

"Thousands. They use them as work animals when need be, because they can seep under a heavy stone, girder, or mass of metal, and gradually all come under it so that the mass is lifted..."

Zendexor: Well, you can't copyright imaginary creatures, so Lovecraft will just have to take it as a compliment that his shoggoths were re-created on Ganymede.

Taking the five Penton and Blake tales as a whole, however, I don't think that plagiarism is a marked characteristic of them. The main parallel that can be drawn is with one of Campbell's own later tales, about an alien species that can impersonate any type of creature.

martians - mimics and fatalists

The Brain Stealers of Mars - the first Penton and Blake adventure - is thematically an extension of Campbell's later and more famous story Who Goes There?

Though written earlier, it takes the idea much further. Suppose the impersonating "Thing" has won - suppose it and its kind have spread rampantly over a whole world.

What does one do?

The centaur-like Martians have an unexpected answer.

"The thushol. So that's what you call 'em." Blake sighed. "They must be a pest."

"They were then. They aren't much any more."

"Oh, they don't bother you any more?" asked Penton.

"No," said the centaur apathetically. "We're so used to them."

"How do you tell them from the thing they're imitating?" Penton asked grimly. "That's what I need to know."

"It used to bother us because we couldn't," Loshthu said, "but it doesn't any more."

"I know - but how do you tell them apart? Do you do it by mind-reading?"

"Oh, no. We don't try to tell them apart. That way they don't bother us any more."

Penton looked at Loshthu thoughtfully for some time. Blake rose gingerly, and joined Penton in his enwrapped contemplation of the grizzled Martian. "Uhmmmm," said Penton at last, "I suppose that is one way of looking at it..."

But the fatalistic Martian "solution" is not good enough for the Earthmen. As Penton later remarks to Blake:

"...Sooner or later, some other man is going to come here... and if he brings some of those thushol back to Earth with him, accidentally, thinking it's his best friend - well, I'd rather kill my own child than live with one of those, but I'd rather not do either. They can reproduce as fast as they can eat, and if they eat like an amoeba - God help us. If you maroon one on a desert island, it will turn into a fish, and swim home. If you put it in jail it will turn into a snake and go down the drain pipe. If you dump it in the desert, it will turn into a cactus and get along real nice, thank you..."

Harlei: The type of problem that could only be solved by blowing up the entire planet Mars, one would think. Yet Penton and Blake manage to extricate themselves, don't they?

Zendexor: Sort of. They're never sure, afterwards, whether the Martian they were talking to wasn't itself a thushol... a nice touch.

Stid: A story of ideas. But not of sensations. We don't get a proper Martian landscape, or a Ganymedean or Callistan landscape in the other stories - except one very inadequate mention (I seem to recall) of orange grass on Callisto... I declare that this isn't good enough for a tour of the OSS.

Harlei: That annoys me too, but you're missing out the exception. The fourth story. A cut above the others, in my opinion.

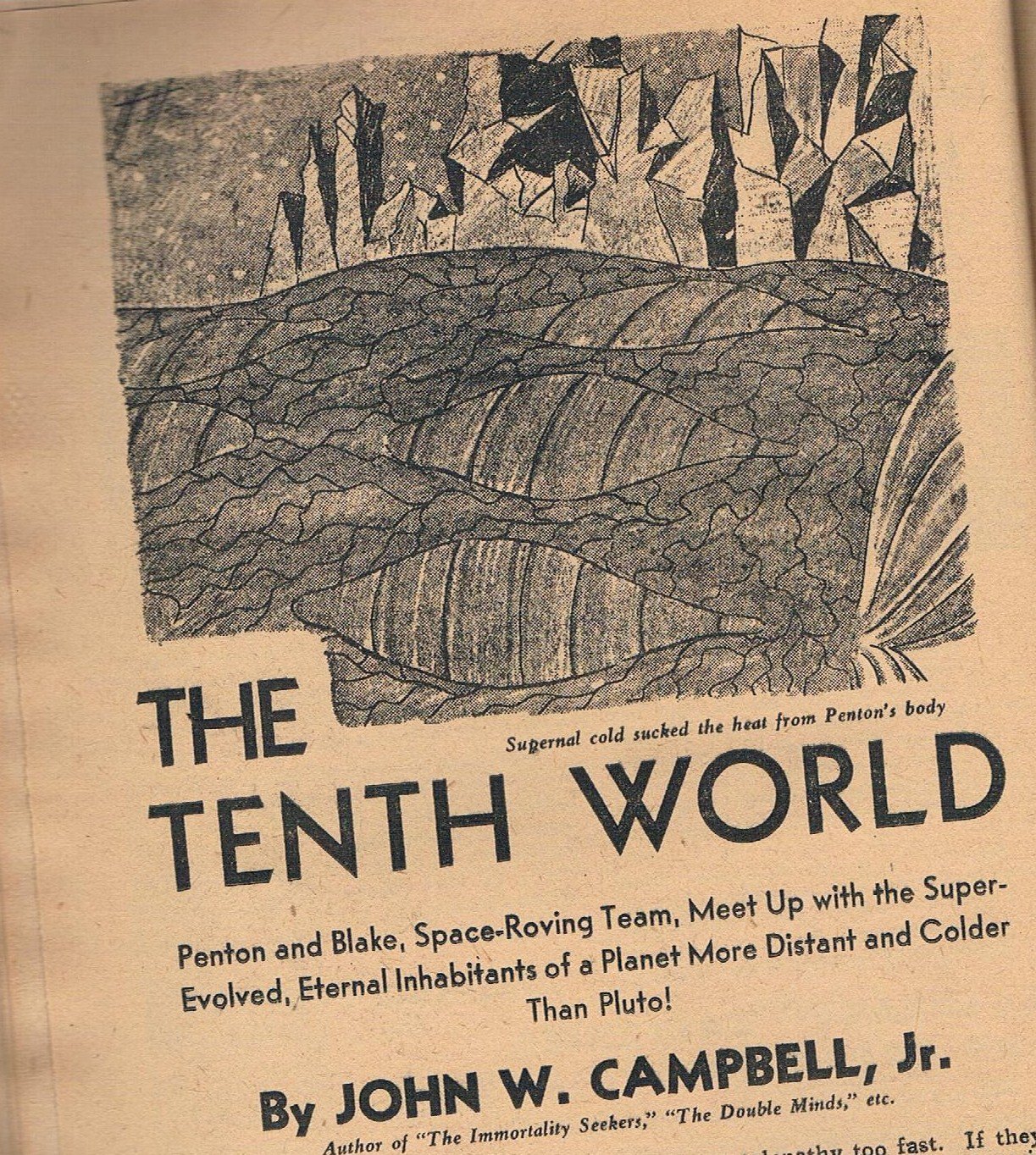

life and death on the tenth world

The scarcity of scenery in the Penton and Blake stories arises partly from the fact that the plots begin in medias res, as the Latinists say. If Campbell had been forced to describe his heroes' first approach - to Mars or Callisto or Ganymede - he could hardly have failed to give us a richer visual impression; at least he'd have had to say something about what the worlds looked like. But as it is, the reader is plonked in the middle of a situation with no proper eyeballing of the planet or moon where the action takes place.

However, this complaint doesn't apply to The Tenth World.

...Beyond the lockdoor lay the utterly bleak surface of the Tenth World. A dim, frozen plain stretched out to a far horizon lost in the pressing darkness of this far, raveling edge of the Solar System. Low in the east, the rising sun was a brighter star, an intolerably brilliant, dimensionless point of light, casting a light that seemed little brighter than moonlight on Earth. But it was bleak, utterly cheerless light. And it was cold, cold.

Barely visible to one side was a lake of clear, sparkling, slightly bluish liquid. Tiny, starlit waves danced and glittered in its surface, moved by some thin, cold wind of this frozen outcast world.

Stid: Adequate. Taking the trouble to describe such a scene is the very least a writer can do, if he's setting his tale thereabouts.

Harlei: It gets more than adequate, it gets good, when we discover the life-forms of that world...

Zendexor: If I may take over here, Harlei, I want to prevent you from giving the game away. I know you're a fan of this tale and you might get over-eager. So let me just say that the encounter with the intelligent inhabitants of the Tenth World is very well done. Their nature, and the practical and philosophical problem they pose to themselves and to Penton and Blake, are, as far as I know, unique in sf literature! Distantly related, perhaps, to the futility of the intelligence of Weinbaum's Venusian vegetables, but here on the Tenth World it's a different evolutionary blind alley, to do with a kind of separation of desire and will... I daren't say any more. Read it.

Stid: You're waxing quite enthusiastic, Zendexor. Is this tale all that better written than the others?

Zendexor: It's better conceived and better planned. But my enthusiasm doesn't last into the fifth story, when the two voyagers go on to the Tenth World's moon. In fact I've even forgotten why that last tale is called The Brain Pirates.

Stid: Well, look it up, then! Do your job!

Zendexor: Ah, but I am doing my job - by being lazy. I'm the canary in the mine, except that it's boredom rather than gas which causes me to swoon off my perch. That's my way of warning the readers not to expect too much from a story.

Stid: A critic should be a bit more specific than that. What bored you?

Zendexor: Mainly, that The Brain Pirates loses all the artistic credibility of The Tenth World by being too glib, too easy in its sudden immersion of the reader in an action-packed civilization.

Penton and Blake stared fretfully through the windows of the Ion. The inhabitants of the satellite were regarding the explorers with a mild curiosity.

"Those birds are waiting with remarkable patience," Penton said, somewhat annoyed. "And this seems to be the local Central Park, wherefore our landing may have annoyed them..."

For goodness' sake, this moon is

well over five billion miles from the Sun, it's deadly cold... and yet

this Central Park mood is what we immediately find upon landing! Sorry to be negative, but the tone is simply wrong.

John W Campbell, "The Brain Stealers of Mars" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, December 1936), "The Double Minds" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, August 1937), "The Immortality Seekers" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, October 1937), "The Tenth World" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, December 1937), "The Brain Pirates" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, October 1938); these five Penton and Blake tales collected in The Planeteers (1966); "Who Goes There?" (Astounding Science-Fiction, August 1938)

See the Callisto page for Penton and Blake's view of a Callistan city and their enounter with a Callistan car.

For later musings by Campbell on Martian life, see the OSS Diary for 25th November 2016.

For my first impressions see the OSS Diary for 3rd and 4th September 2016.

For a reference in The Brain Stealers of Mars to an earlier visit to Venus see one of the Venusian Zone CLUFFs.