h p lovecraft - misunderstood?

a view by

antolin gibson

[ + links to: H P Lovecraft - The Haunter of the Dark - The Whisperer in Darkness - The Dunwich Horror - The Call of Cthulhu ]

the note of cosmic awe

Very often, Lovecraft is a writer not of terror, but of awe. It is the immensities that are so important to him – the eons of time and cosmic distance, of height and depth, huge architectural scale, technological achievement – all ingredients of Olaf Stapledon's work, but which in Lovecraft bring on the emotive adjectives which have brought so much critical disfavour.

cyclopean ramparts of an ancient Antarctic city

cyclopean ramparts of an ancient Antarctic cityStill, perhaps look at it this way: Lovecraft is the great emotive analyst of fantasy literature! If the formulaic adjectives of terror are seen rather as the code-words of awe, and Lovecraft as an emotive kind of Olaf Stapledon, rather than as a failed M.R. James, then a fresh dimension of Lovecraft's universe – and of this complex writer's own intimate relationship with it – can be seen.

For instance, in the following description from At the Mountains of Madness, of the explorers clambering around the ruins of an alien city: if we take away the Lovecraftian adjectives would we not have something quite akin to Stapledon's Last and First Men? The vast spaces, the great depths of time . . .

Only

the incredible, unhuman massiveness of these vast stone towers and ramparts had

saved the frightful thing from utter annihilation in the hundreds of thousands

– perhaps millions – of years it had brooded there amidst the blasts of bleak

upland. “Corona Mundi – Roof of the

World - ” All sorts of fantastic phrases

sprang to our lips as we looked dizzily down at the unbelievable

spectacle. I thought again of the

eldritch primal myths that had so persistently haunted me since my first sight

of this dead antarctic world – of the demoniac plateau of Leng, of the Mi Go,

or abominable Snow Men of the Himalayas, of the Pnakotic Manuscripts with their

prehuman implications, of the Cthulhu Cult, of the Necronomican, and of the

Hyperborean legends of formless Tsathoggua and the worse than formless star

spawn associated with that semientitiy . . .

a weird cosmic sweetness?

Lovecraft's work belongs to at least three genres – science-fiction, supernatural horror, and heroic-quest-fantasy. There is more than a streak of inspired nonsense in Lovecraft – in the vein of Clark Ashton Smith and perhaps even of Mervyn Peake – and there is also more than a hint of self-spoofing. He was poet, essayist, novelist, and short-story writer. His work divides opinion as perhaps no other author. His approach is sometimes dreamlike and mystical, other times scientific and meticulous. His description in At the Mountains of Madness of those explorers clambering over the ruins of the cyclopean city they discover in the Antarctic is surely one of the best examples of the meticulous kind in the sheer loving detail displayed, and the more detail accrues the more one has the urge to warn the explorers to make their escape! A sense of menace increases with the detail – such as happens in a more enclosed way in another meticulous detail-loving writer, M.R. James, for example in his The Treasure of Abbot Thomas.

a zoog

a zoogI wonder why critics so rarely allow for a certain fortuitous sweetness arising from an inspired fiasco? The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath is undoubtedly fiasco, style-and-content – and surely partly intended to be so! (c'mon, all you critics, such as Edmund Wilson, Colin Wilson, Lin Carter, give Lovecraft a break in the matter of style – for Lovecraft sometimes means the absurdity!) – and, in much of the author's work, there is at least a hint of this joyous “who cares” spirit which I personally find sweet, like thick relentless syrup. Such a chance-value emerges from both the floridness and the awe. The delightful "zoogs" in The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath and the frantically waddling albino penguins in At the Mountains of Madness: who in their right minds would not want to snuggle up to these? And indeed all the ludicrous Lovecraftian adjectives – whether they are a part of a code of awe or else a flat-footed literary style – surely harbour a dissonance, an irony, even in such weird cosmic sweetness; all part of the contradictoriness of this writer, and an odd gentleness amidst the cantankerousness of the man.

lovecraft and dunsany

Stories such as the Dream-Quest and The Cats of Ulthar are said – by some critics – to be in Lovecraft's “Dunsanian” phase but I think these of Lovecraft's stories are far too cheeky and flippant to be truly “Dunsanian” in spirit, indeed they are a type of the “picaresque”, and far too lacking in the elaborate symbolism in which the amazing Lord delighted.

Admittedly there is an influence on the early Lovecraft, in whose view Dunsany was one of the Big Three in the literature of supernatural fiction, the other two being Poe and M.R. James (no mention, as far as I know, of the other celebrated James – Henry - and his The Turn of the Screw). But Lovecraft from the start struck out on his own – and there is another consideration in this whole “Lovecraft-Dunsany” thesis apart from Lovecraft's emphasis away from symbolism and towards a version of the picaresque in early stories: for these tales contain the seeds of the Cthulhu Mythos, seen through the uncertain prism of dream.

The lines of the prism hardened later but the dreamlike outlines were there from the start – and more. For there are vignettes of the cosmic struggle that looms large in the later stories, developed to a perfection in At the Mountains of Madness. For instance, in the Dream-Quest we learn from the old Pnakotic Manuscripts that:

. . . the hairy cannibal Gnophkehs overcame many-templed Olathoe and slew all the heroes of the land of Lomar . . .

This is Hard Fact that could just as well be read out on the Channel Four News, as appear all fuzzy in a dream. So yes, the early Lovecraft is more dreamlike, certainly influenced by Lord Dunsany, but Cthulhu nevertheless dwelt in this as much as in the later “scientific” tales.

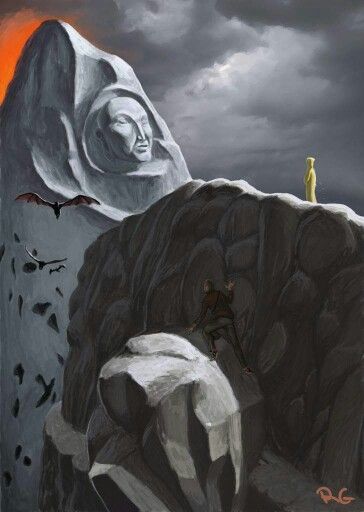

Mount Ngranek with its carved image

Mount Ngranek with its carved imageIn the Dream-Quest the mountain “Ngranek” is a kind of palimpsest-structure of the myth overlaying the structure of the true Quest. And the following passage concerning Randolph Carter surely has more in common with At the Mountains of Madness than anything in Dunsany:

At last, in the fearsome iciness of upper space, he came round fully to the hidden side of Ngranek and saw in infinite gulfs below him the lesser crags and sterile abysses of lava which marked the olden wrath of the Great Ones. There was unfolded, too, a vast expanse of country to the south; but it was desert land without fair fields or cottage chimneys, and seemed to have no ending. No trace of the sea was visible on this side, for Oriab is a great island. Black caverns and cold crevices were still numerous on the sheer vertical cliffs, but none of them was accessible to a climber. There now loomed aloft a great beetling mass which hampered the upward view, and Carter was for a moment shaken with doubt lest it prove impassible. Poised in windy insecurity miles above earth, with only space and death on one side and only slippery walls of rock on the other, he knew for a moment the fear that makes men shun Ngranek's hidden side . . .

Here are echoes of Dunsany's brilliant Pottarnees, Beholder of Ocean, but in any case, apart from such imagery in the so-called “Dunsanian” stories of Lovecraft, the loudness and solemn cheekiness of this writer's approach separates him from the mood of Dunsany.

However, linking the two writers, there is a thematic element, one of the most elusive and seductive areas of fantasy – that of the Borderland. The fleeting but imperative boundary between fantasy and perceived reality.

And the connection is not between genre-stories of either writer, but between the “outsider” motif in each. In this regard, with the hero as “outsider”, there is much in common between, say, Lovecraft's The Haunter of the Dark and Dunsany's A Shop in Go By Street. For both writers know the haunting, tantalizing, and ever retreating presumption, of the suffering soul within beauty and awe, that elusive parallelism of the everyday with the numinous that is always just beyond comprehension. This poetic “presumption” of the Borderland is spectacularly achieved in Dunsany's flawed masterpiece, The King of Elfland's Daughter. (And in William Hope Hodgson's The House on the Borderland the challenge is met in truly awe-inspiring manner in the realm of cosmic horror). In Lovecraft's The Haunter of the Dark, the Borderland-area is deftly evoked in the streets around Federal Hill, and the tormented outsider-character of Blake parallels not only the traveller in Dunsany's A Shop in Go-By Street, but also Doctor Haynes in M.R. James's The Stalls of Barchester Cathedral.

ceremonial and journalese

The awakening of Cthulhu in The Call of Cthulhu is central to the Mythology – but also a good place to reflect not so much on Lovecraft's style as on the critics' robotic evaluation of style, and I have to say that when I hear critics go on and on about style, I tend metaphorically to reach for my (metaphorical) gun. One of the worst examples I have come across is Colin Wilson's remark concerning David Lindsay, who according to Wilson “could not express his deepest ideas in words.” When I read this bit of criticism, my jaw (metaphorically) dropped, and I wonder if anyone has ever written such a fatuously dismissive literary remark. It is because Lindsay's words are those words wot he wrote, that a masterpiece like wot A Voyage to Arcturus is and all the wonder wot is there, came about, wot is abosolutely and successfully all about deep ideas. Now that's style! Why did Wilson – who recognized Lindsay's genius – so persistently miss the point? The way the words are put together is the style: the order and the emphasis and the dissonance and the harmony etc, the whole lot. Thus in A Voyage to Arcturus, the heart-breaking death of Sullenbode is written with an extraordinary jagged harmony. If it were written any other way – if it were smoothed out with a Wilsonian Word-Roller - it would not be the transcending tour-de-force that it is. And much can be said of the criticism of Lovecraft's style by the other Wilson I have mentioned – Edmund – and by Lin Carter and others. I really don't understand the whole approach.

Cthulhu is awake

Cthulhu is awakeBut getting back to Cthulhu's awakening, this episode is extraordinarily vivid and skilfully paced, replete though it is with Lovecraft's florid (gorgeous) verbs and adjectives, and thus it works because thus it is stylistically. And it works because of the author's penchant for an introductory ceremonial of horror rather than the impressively economical expression perfected by such as M.R. James and Stephen King which is ever fresh and immediate and, in important particulars, unevasive! A good example of this ceremonial of Lovecraft's approach to horror comes in this episode of the awakening of Cthulhu by the crew of the captured ship, Alert, and is offered to the reader by the narrator of the story, Francis Wayland Thurston, who has managed to get hold of an account written by one Johansen, a sailor, concerning the emergence of Cthulhu's tomb from the depths of the sea in an earthquake:

Johansen, thank God, did not know quite all, even though he saw the city and the Thing, but I shall never sleep calmly again when I think of the horrors that lurk ceaselessly behind life in time and in space, and of those unhallowed blasphemies from elder stars which dream beneath the sea, known and favoured by a nightmare cult ready and eager to loose them on the world whenever another earthquake shall heave their monstrous stone city again to the sun and air . . .

Such preludes to the bare facts of the horror tale are, to some critics, irritating and waffly, to others simply quaint, and to yet others are utterly essential to Lovecraft's mythical frame – a frame that is at once delimiting and vast. But I'll put this ceremonial aside to touch on another phase even though the ceremonial is one of the main characteristics of Lovecraft, as well as being one of the main targets of negative criticism.

Innsmouth - not a good place to go to church

Innsmouth - not a good place to go to churchThere are among his stories certain examples which discard this feature entirely, which shows it is not an indelible characteristic of his putative “bad style” - and of this group of stories, The Shadow Over Innsmouth is perhaps the most striking. But this story, with its sober (indeed, at times soberly journalese) approach and with its dreamlike seedy quality, is not untypical among the author's works. It has that stamp of awe – but this now seeps through the seediness rather than glares through the cosmic vastness: it seeps through the dislocation and dysfunction of a whole community. It is sensed through an inexpressibly melacholy filter of frayed legend, run-down streets and warehouses, alcoholism, cult and decadence.

getting out of town...

getting out of town...Olmstead's escape from the Gilman House is a classic of mood and pace in the manner of Harker's escape from Castle Dracula: the very soul is threatened and, as with Bram Stoker, Lovecraft skilfully and suggestively engenders in us a creepy heedfulness of the true horror of this death of the soul. The corrupted folk of Innsmouth, who gain eternal life, must descend to the depths of the sea, without breath and without the blink of an eye – without humanity – to serve the Deep Ones.

The essential Lovecraft! Have I got there? Who knows. There are so many facets, so many dimensions. But I think it is in Innsmouth - and I wouldn't mind booking a holiday there, if someone comes with me – that can be seen the debris of human wreckage, legend, decaying town, in which the reader is given the purchase to view the unimaginable, to savour the hugeness of the universe through the frailty of a great imagination, where fantasy of the most alien is conveyed from a limbo of ordinariness, in which time and action are stilled in tension, and we are given the gift of a cosmic reverie.

the Innsmouth look... this gent won't smoke much longer

the Innsmouth look... this gent won't smoke much longer