william hope hodgson:

a view

by

antolin gibson

[ + link to: Far Future ]

the J Humphries illustration gives some idea of the size above ground of the Last Redoubt (over 7 miles tall) though you can't see what's below ground

the J Humphries illustration gives some idea of the size above ground of the Last Redoubt (over 7 miles tall) though you can't see what's below groundHodgson is a painterly writer, but expressionistic, not impressionistic. His outlines are clear and well-defined. He marshals startling images which – as far as they are connected with ideas at all – are pictorial, not philosophical. In this way, an astonishing environment is created, one of the most tactile of fantasy-scapes. In their way, his works echo the fantasies of William Morris, which C.S. Lewis called a “watercolour world” - but, in Hodgson's case, the painterly style is more that of Munch (such as, “The Scream”) than Girtin (such as, “Hills and River”)!

A certain element of the absurd may go with grandeur - see the operas of Wagner. But it is a balance: the pyramid of the Great Redoubt in The Night Land is outrageously absurd, and the underground Fields beneath it even more so, but as images in the surroundings of huge, brooding, dispassionate forces, the Great Redoubt and the Fields are moving concepts, pitiable, and with a strange, poignant meekness in the context of a dying night-shrouded Earth.

The great Gorge in The Night Land is an allegory – it might seem – of the repressed human spirit breaking free. The pendulum-swings of emotion, from hope to despair, blend into the very lights and shadows of the landscape, and the ancient smouldering sea at the end of the gorge is one of the wonders of fantasy – and the sending out of the Master Word to the beloved across the darkness of the world is one of the most haunting calls in romance.

And buried in the epic tale of shadowed monstrosities, portents, and vast enigmatic spaces, is the need of a person who must tell . . . but knows he can never make clear. It is the story of a poet. The hero is also immensely strong, urbane, rather in the manner of E.R. Eddison's Lessingham.

The Night Land is like a wave that has its own volition. With the idea of the Night surrounding the vast pyramid of future civilization, and with the archaic (but not always stilted) style, allowing surprising embrasures of psychological insight like the embrasures of the pyramid itself allowing views upon the Night Land – with these tools, as it were, and scarce more elaborate refinements, the author is able to sit back, with the thick dark wave in motion...

I think in mood – the slow motion and the whole dreamy texture of the fantasy – Hodgson is most akin to Dunsany. In the latter's Idle Days on the Yann, the description of places at the beginning, with those indefinite boundaries of elusive fantasy, is similar in tone and effect to Hodgson's lie-of-the-land, from the great pyramid of the Redoubt in the second chapter. But instead of the Night, the quality of Dunsany's fantasy-atmosphere, so wonderful and haunting to breathe, is the melancholy yet keen light of the early dawn.

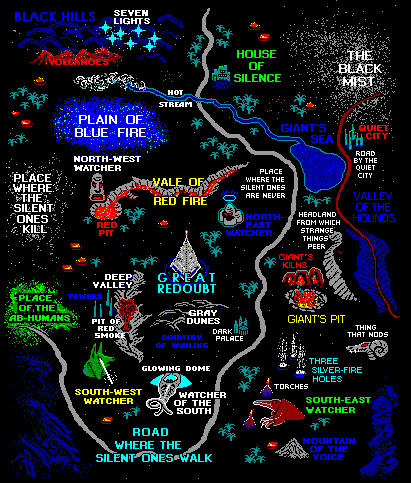

But there is another distinction. The Night Land's lie-of-the-land is real - that is, whatever alternate universe springs up whenever a fantasy-writer pens his work, precise maps must exist of The Night Land: - maps of the Vale of Red Fire and the Plain of Blue Fire, the Country Whence Comes the Great Laughter and the Giant's Kilns, etc. The geography is precise, delineated with a firmness of conviction, whereas in Dunsany's Idle Days on the Yann and the rest of his great oeuvre, the country is Dream Land, by a subtle lilt and an inflection of tone; a certain fleeting irony, perhaps. Certainly nothing like the following passage from The Night Land:

And, strangely, I heard the sand to stir at my back, and I looked round very quick, and the sand rose upward in parts, and sifted back, and there came to my sight odd things that move and curl about.

And immediately, before I knew which way to go, I knew that the sand did shift under my feet, and did work and heave, so that I was tottered, and was shaken also in the heart; for I knew not what to think in that instant. Then did I perceive that I was all surrounded, and I ran swift upon the heaving sand, unto the edge of the fire-hole, and I turned there, and looked quickly; for I did not know what this new Terror should be.

And I saw that a Yellow Thing did hump upward from out of the sand, as it had been a low hillock that did live, and the sand shed downward from it, and it did gather to itself strange and horrid arms from the sand all about it. (Chapter VII.)

the House of Silence - a place to avoid at all costs

the House of Silence - a place to avoid at all costsDelineation in movement . . . even in the silent Watchers, there is a vibrancy of malice in which there is movement, horror, beauty, intent, woven thus in the author's creations of fantasy and but rarely linked to preconceived mythic types. They are fresh and new from the author's mind.

Why this cauldron of monsters, of brooding entities?

I am nearly certain that the whole monster-scape is an expression of the teeming loneliness felt by the poet, in wonder of the universe, and in the isolation of his condition and calling.

For in verity, when the world did split and burst, and the oceans rushed downward into the earth, and there was fire, and storms, and a mighty chaos, surely it was proper to think that the End had come. Yet was it, in truth, but the beginning of hope of a new Eternity of Life, so that out of the End came the Beginning, and Life out of Death and Good out of that which did seem a dire matter. And so it is always. (VIII)

But this rarely professed optimism is surely the very loneliness of the poet's cry – the heroism amidst the palpable doom – amidst the stately and haunting portentousness of the End Time. It is the affirmation of a poetic imagination which makes the hopelessness all the more moving and this I think is the important thing for this writer. But when we come right down to it, there is really no hope in Hodgson's Night.

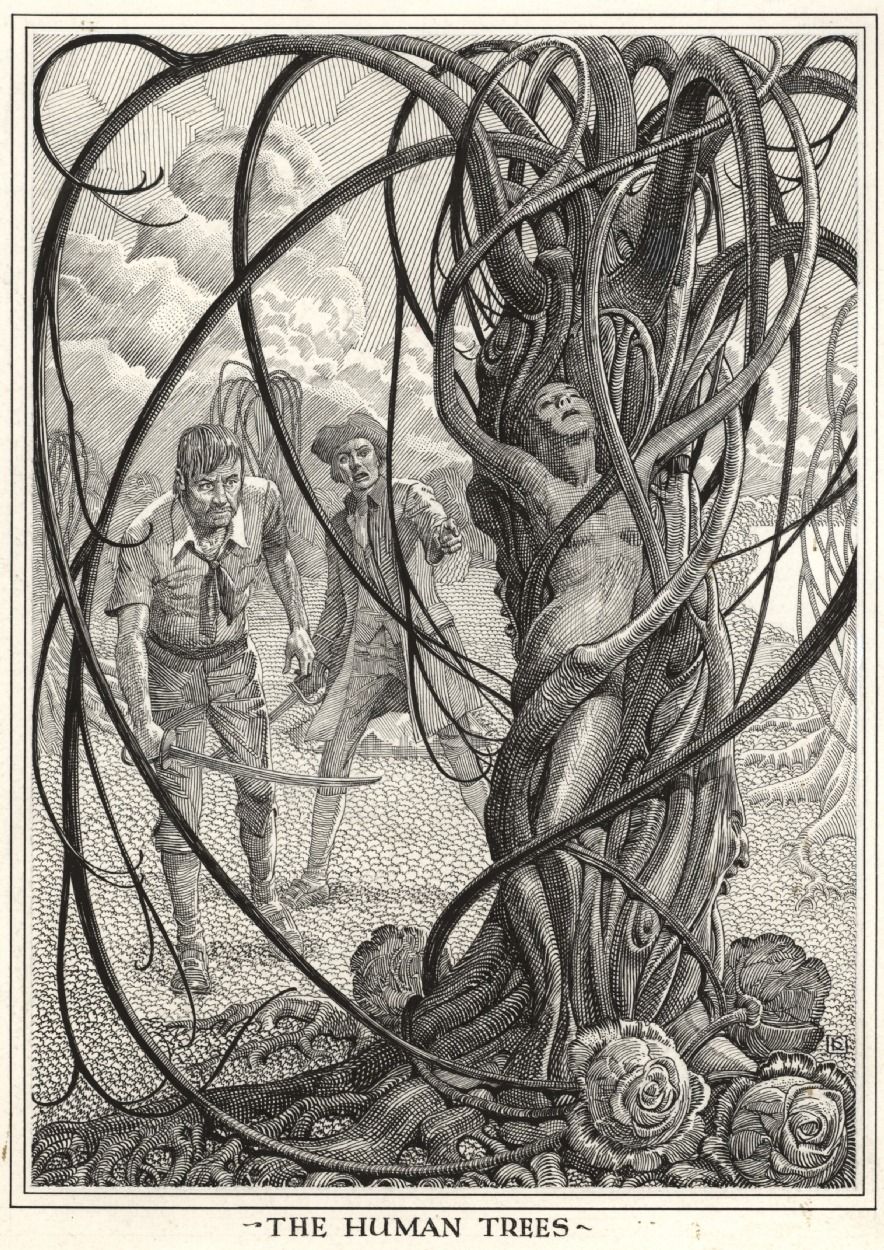

In some rare fantasy, there is a region between mood and plot. This region has different scales of tension, equilibrium, ponderousness. It is the Kafkaesque – but certain key stories are more fully in the realm of fantasy than are most of Kafka's works – thus such fantasies as Mervyn Peake's, Clark Ashton Smith's, William Hope Hodgson's. This most curious region can link humour, horror, the obsessively practical, and the mystical; and therefore links such works as Letters from a Lost Uncle (Peake), Marooned in Andromeda (Smith) and The Boats of the Glen Carrig (Hodgson).

the Watchers move as slowly as continents

the Watchers move as slowly as continentsTo myself, I've called this region “through-disjunct”. There is a getting through, in a way; albeit it sometimes is almost a slapstick, playful way; or a nightmarish way. Everything seems slightly off-the-familiar (though it might be specifically about something that is familiar). Thus belongs the whole section of the making of the kite in Hodgson's The Boats of the Glen Carrig.

This “through-disjunct” - as well as the “splendid sombre images” as C.S. Lewis called those of Hodgson - amount to the pure and the sui generis, the very soul of Hodgson. When he tries more conventional forms – such as the more conventional thriller or ghost story – the result is rather a spectacular failure. Carnacki the Ghost Hunter, a collection of stories linked by the Holmesian character of Carnacki, drops the archaic language of The Night Land and Glen Carrig (which some might find a relief) but the paucity of Hodgson's skill in writing about characters is revealed. The vaguely Holmesian Carnacki is in desperate need of depth, some departure from a pipe-smoking archetype, some quirk – anything! There are no sombre images to compensate, no solidity of the utterly alien supernatural (or science-fictional) strangeness that is ever and again coming out of the dark.

The poetry has been dropped. The sense of epic sweep and haunting otherness - dropped. The crucial matter was not just a question of archaic style - The House on the Borderland dispenses with this too and it is a gem, a wonderfully vivid story (though in a different and lesser way and more conventional way than the author's rugged miraculous masterpiece, The Night Land).

How different from the halcyon fantasies of J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, and the tradition of the fantasy-quest going back to The Faerie Queen of Spenser - all those works in which good is set against evil, and in which, even in the darkest mine or forest or castle, there is the promise of light – at the end. In the works of Hodgson, the light is doomed, though it takes millenia for the last flickering expression to die (millenia considerably speeded up in The House on the Borderland with the cosmic journey of the Old Recluse). In The Night Land, the Earth-Current is fading, the Lesser Redoubt dispersed. The House on the Borderland is even more doom-enshrouded, for that extraordinary place is far from being a Redoubt and is rather an extension of the darkness. It echoes many of the reclusive houses of troubled hermits, in the works of such as M.R. James and H.P. Lovecraft; how different from their halcyon counterparts, such as Tolkien's Bombadil and Lewis's Hermit of the Southern March! The House of Hodgson's novel, as first encountered, could be seen as emblematic of the quietus and passionate solemnity of the author's major work: it is perched over a mighty chasm, at the far end of a great spur of rock:

In fact, the jagged mass of ruin was literally suspended in mid-air (The House on the Borderland Chapter 1).

Here we have the vastness, precariousness, and loneliness so essential to the author - in a single image.

The critic may come by useful pegs in the appraisal of fantasy-writers, though these are apt to change as the explorer skirts around the limitless surprises. My most recent pegs – which usually come as polarities – are “halcyon” and “reclusive”, for these seem to clinch two kinds of emotional dynamic. The reclusive, such as H.P. Lovecraft and W.H. Hodgson, have a love (and I think that is the right word) for loneliness – often represented by the man who is cut off, and upon the edge of cosmic awareness (a clear surrogate of the authors!). Edgar Allan Poe has expressed this need and this longing more succinctly than anyone, but Hodgson has explored the territory of this morbid vastness more exhaustively. It is an extraordinary journey of remoteness in relation to the human obsessive consciousness: no other author has unrolled the tactile and near photographic vision of this reclusive fantasy more vividly that Hodgson. He sets such human habitations as the House on the Borderland, and the Great Redoubt on the edge of the Night Land, as points of departure, as the final and flickering links with civilization – but then the author casts adrift, is alone, in the purest and most comfortless imagery of vastness.

the Recluse eyes one of his besiegers

the Recluse eyes one of his besiegersOf the evil of Hodgson's cosmos, I don't think there is any doubt – just as there is none about Lovecraft's. The following passage in The House on the Borderland could indeed have come from Lovecraft's pen:

. . . before, I felt some fear, though almost of an impersonal kind. I may explain my feeling better by saying that it was more a sensation of abhorrence, such as one might expect to feel, if brought in contact with something superhumanly foul, something unholy – belonging to some hitherto undreamt of state of existence. (Chapter V)

And yet there is a need for this “undreamt of state” that apparently only the unholy can bring about. The same of course could be said of many a witch's coven and magician's pact: deemed essential to break the tedious norm! Yet rather than power, it is a willing victimhood that drives the central characters of Hodgson and Lovecraft – very different in this regard from the tendency in M.R. James and Lord Dunsany.

Hodgson's The Night Land has profound similarities to The House on the Borderland (which was published some four years earlier) but a far more profound divergence. The similarities include the cosmic scope and imagery; the lone explorer half in love with the sombre inhumanity of the “undreamt of state”; and, most important of all, the personification of a wildness of fantasy which puts human feeling and motives in a subordinate place. The divergence between the two books appertains to this very personification, however, for in The House on the Borderland there is a pattern and a symbolism to the fantasy, whereas in The Night Land there is a formless expressionistic thrust that is the soul of madness. So that, what C.S. Lewis called the “unforgettable sombre splendour of the images” that The Night Land presents, could be said of those images in The House on the Borderland but the images in the latter book are in an arabesque whose cryptic meaning is for the reader to unlock. The static gods of the arena – which have a note of Arthur Machen's reworking of classical motif – surround a projection of the House in green jade – in Chapter III of The House on the Borderland - as though the audience of a macabra parallel history is watching an idealized projection of the author's own grim lonely redoubt: the “author” being the misanthropic “old man” who leaves the manuscript for posterity. And the author being Hodgson...

the survivors of the "Glen Carrig" discover the Land of Lonesomeness

the survivors of the "Glen Carrig" discover the Land of LonesomenessThe lonely recluse (wayfaring through the cosmos) is the surrogate explorer of the unique type of the author's wayfaring imagination. The reclusive old man is very much the man of action – as Hodgson was - finding youth and motivation in the defence of his precarious sanctuary. Hence, with the attack of the “Swine Things” in Chapter VII, he applies himself to the rifle-stand with vigour. There is, in Chapter VIII, what I call the “opt-out-whim” which is a way – also to be found in Henry James's The Turn of the Scriew - to see the whole tale psychoanalytically, and devoid of supernatural content. It is curiously effective and in itself chilling, the way the opt-out is set up: with the alluring possibility that the old man is a maniac, and that his sister is terrified of him. But – and this may be a testimony to the novel's wonderful presentation of “undreamt of things” - the opt-out does not seem to matter or to signify in the end. We are still upon the old man's journey - perhaps the fact that he is not given a proper name is significant for, in a certain sense, he is Everyman . . . or, that is, Everyman in his darkest and most yearning dreams. But this said, the mid-part of the tale, the “time of waiting”, when the old recluse, with an access of youth, is rushing around and securing the House, checking on his sister, and his wounded dog, Pepper – this part, even while the “opt-out” for the reader is at its most seductive, is from a purely dramatic point of view essential: juxtaposing human energy (and human frailty) with the cosmic journey to come. The rather clumsy humour of this portion adds to the sense of frailty: perhaps the mind of the recluse is indeed going? When, at the entrance to the tunnel part-way down the great chasm, he is frightened by the echo of his own breathing, he is sufficiently unstrung to postpone further explorations.

A thought here, that must be left dangling unsolved as all such thoughts must be left, that the three great works of dark exploration - The Boats of the Glen Carrig, The House on the Borderland, and The Night Land appear in some ways strikingly prophetic of No Man's Land and the trenches and the hopelessness of the First World War, in which Hodgson was killed - well nigh irresistible to believe that he felt some presentiment... but there, the idea is just left . . . dangling . . .

But, the darkness aside, with Chapter XIV of The House on the Borderland, a Dantesque note comes in, Dante himself of course being a Master of depicting the Light shining amidst Darkness – with, in Hodgson's tale, the appearance of the Beloved. At the same time, there is the loss of portions of the Manuscript which the recluse leaves behind (thus letting the author off the hook as regards a detailed explanation of the old man's lost love). Altogether, the lyrical note achieved at this point reminds me of Dante's beautiful lines in Canto 1 of the “Inferno”:

Temp'era

dal principio del matino

e'l

sol monava'n su con quelle stelle

ch'eran

con lui quando l'amor divino

Mosse

di prima quelle cose belle . . .

(37-40)

“The

hour was morning's prime, and on his way

Aloft

the sun ascended with those stars,

That

with him rose when Love divine first moved

Those

its fair works . . .”

(Henry Cary's translation)

And still, there is the duality underlying the tale: the House is evil (as the Beloved herself says) and yet it is the only place where the lovers could meet again. It is as though that pile of stone upon the Borderland of the Earth and the dark unknowable Cosmos, was the torpid and fretful and bitter ruin of a life, a human life past all endurance, for which the Supernatural, even to the end of all things, was the only relief and, strange to say, the only comfort to be had.

For The Night Land see A view from Man's refuge on far-future Earth.

>> Authors and Far Future