uranian throne - episode six

the infrastructure throbs

by

robert gibson

[For the story so far, see: 1: Dynoom; 2: Hyala; 3: the nebulee; 4: Exception; 5: the lever of power]

[ + links to: Glossary - Timeline - Survey of Ooranye - Plan of Olhoav -

guide to published stories ]

The talented side of him welcomed the challenge. Dismal though the outlook seemed, it brought a prospect of action: and his imagination, with the mindful intensity required by his office, clasped that vista.

The likely high price of wading into a mess did not daunt him. Necessarily adept at statesmanship, a Noad must take joy in nudging, braiding, stitching life's currents.

You may remark that this amounts to a definition of statesmanship anywhere in the cosmos, not just for a city on Ooranye. We would not argue that point except to remark that the stakes are higher here: a Uranian Noad, if faced with failure, is exposed naked to the judgement of history, for here on the Seventh World a leader who fails is unable to spread the blame. Nen cannot plead entanglement or obstruction by written laws, of which we have none. Nen is responsible entirely alone.

Barlayn Lamiroth had an inkling that some political abyss might lie ahead, because the ominous placards, the disquieting rumours of the past few days, were suggestive of a social cancer against which he knew of no defence. Not only to himself but also to the scholars, historians and planetographers whom he had hastened to consult, the moral darkness spreading through Olhoav was of an unfamiliar type; all they knew was the bare fact, that some manipulator of emotions had ignited backgrounder resentment, presumably as a tactic for the stoking of revolution.

No history or folklore gave any hint of how to deal with this. The problem could hardly even be discussed, so strong was the taboo against using the words "backgrounder" and "foregrounder" in polite discourse. Except, that is, with Dynoom - it was acceptable to talk about such things with the city brain. Only, it seemed that to do so would do no good, for the Noad had just learned that he could not expect the decisive measures he wanted from Dynoom.

Barlayn concluded that he himself would probably have to kill the rebel leader, the mysterious "Weigher".

As the city's rightful Noad he would be within his rights to take a life for reasons of State, although never before, in his six-thousand-day reign, had he needed to exercise such dire responsibility. His heart was heavy at the thought. To be in the right was bleak consolation.

In order to brace himself for the deed he might 'plant', in one mental 'pot', a snarly attitude towards the Weigher, or better still a sprig of contempt, to aver that this Dempelath person was nothing special, a mere pest. In fact, might it even be unnecessary to kill him, after all?

Ah, if only everyone could calm down and allow him to rule a sane city! If only backgrounders could recover their common sense and see they were being deluded! Noad Barlayn Lamiroth frowned as he tramped the steel floor of Olhoav, the thump of his boots enacting his need to stay in touch with the urban fabric and its people. And he would keep his boots on firm metal even if few others did...

He spotted a placard. It had been erected close to where a helical tower's up-slanting walkway began.

WORDS ARE USELESS

THE FORGS WON'T LISTEN

SHOVE THEM ASIDE

Barlayn glanced about. About a dozen other walkers were closer to the divisive sign than he was. Two of them - only two! - were in the work-trance. The others were fully awake. Some of these wakeful ones, who had seen the notice, now saw him. They gave him duly respectful nods and saluting gestures, but then they hastened their steps away, as though they were anxious to avoid an exchange of words with their Noad... Whiffs of wrongness...

Grimly lengthening his own stride, Barlayn Lamiroth rounded a kidney-shaped plaza, where, under an overhanging thicket of walkways and globular mansions, he almost bumped into another placard:

HENCEFORTH

IT'S YOUR STORY!

SEIZE THE SPOTLIGHT

FROM THE FORGS!

He took a back-step and again glanced around. This was a busier area, where as many as thirty pedestrian workers were within hailing distance. Fifteen of them were carrying boxes under their arms: not surprising since this precinct was the economic umbra of Olhoav's major phial-factory, the Eneglor; yet oddly no more than three of those burdened backgrounders strode in the smooth gait of the work-trance. The other twelve were far looser, less firm in their step. They were rambling, indecisive, awake... and they outnumbered the trancers four to one! What was this epidemic of wakefulness?

Perhaps better not use the term "epidemic", thought the Noad. Not an auspicious word. Nevertheless, no denying it, four-to-one was a severely anomalous wake/trance ratio for the Eneglor area -

And then he saw the hook-armed, clenched-fist salute of some "wakies" who had stopped to read the placard.

As if sensing his stare on their backs, they looked round guiltily and hurried on.

He took a step after them and stopped. What would be the use of pursuing, pretending bafflement, demanding an explanation...? The manifestations were sadly comprehensible. Out of them Barlayn Lamiroth was able to sift his own dire "regress report" on Olhoav, to show what lay ahead if nothing was done to rescue Olhoavan society.

The work-trance must dissolve as backgrounders became more status-conscious, more apt to brood wakefully upon the category to which they belonged, and less willing to relax into their daily few hours of unconscious co-operation. Thus a new alertness would prevail. It would gain at the expense of the smoothly traditional, harmoniously productive, instinctive mode; the old way of living which had evolved over aeons with incalculable benefit to all. That mode would die, and consequently everyone would have to work harder and longer, suffer more boredom, be forced into conscious attention to tasks which formerly had been effortlessly accomplished in a condition akin to calm dream...

The prospect was one to make any foregrounder sick at heart. Backgrounders, too, would eventually loathe the waking drudgery - but not at first. For a while, their egos incited by Dempelath, they would be sustained by the false promise of plot-stardom for all. The deluded fools! As though there was room for every citizen to be a Noad, a Daon, an omzyr or a vigilee...

Barlayn's reflections were interrupted by a metallic sound, a faint grind of heavy steel...

2

He turned - and thank goodness the old secure pride, in which he was accustomed to stroll the streets among his people on a normal day, was revived by what trundled into view.

It came at walking speed, around the curve of the steel alley. It was a six-wheeled cylindrical tanker, painted in glowing blue. Fore and aft extended a silver roof-rack; a banner was slung down its length; its flapping cloth displayed the words, "Welcome the New Daon".

The thing was a seyyo, a customary-car, by which the populace signalled their rejoicing at a new appointment to the dayonnad. This perfectly traditional, leisurely juggernaut could not but lift the Noad's mood. What a welcome sign it was, of healthy political survival!

Barlayn wondered if Daon Sunwa Nerren had yet seen it. Probably not: it was proceeding towards her, rather than coming from her direction. Well, when she did encounter it, she'd be most touched...

He noted that a dozen figures were standing upon the roof-rack of the seyyo. They were waving to the spectators, who - including the Noad - waved back. Yet one particular person, seated up front, his forearms on the float's prow-rail, did not wave. He was a thick-set man whose boots dangled and clunked against the metal nose of the vehicle as it lurched onward. Barlayn recognized the fellow: a senior factory hand, the sort who could be termed an upper-grade backgrounder, which is to say, someone risen sufficiently above the faceless category of the general population to earn mention by name in some tale. A stalwart class of character; a type who - the Noad hoped - would most likely remain content with his lot and be resistant, therefore, to the blandishments of the Weigher -

As the float came alongside him, the Noad greeted this person by name. "Smevedem!"

Smevedem grinned widely and lifted one finger. While the Noad inwardly shrugged over this puzzling gesture, a worse startlement supervened:

An unbelievable convulsion of the float! It suddenly tilted from side to side as though playfully pretending to be battered by waves!

Suppressing his dismay at this unnatural ebullience Barlayn bent his gaze to see how the trick was done: he was able to note that although the wheels, first on one side and then the other, were pushed up for an instant as if jacks had been placed under them, in actual fact it was the floor of the alley itself that had jerked, rather like a twitch of irritated skin.

This happened three or four times in rapid succession, a gleeful bobbing in excess of energy, so it seemed to the uneasy Noad. The effect betokened an astounding control of city infrastructure. Not to mention an expenditure of power at which the Noad shook his head. Any explanations, excuses to be found? Perhaps, on a day like this, high spirits were worth paying for...?

Anyhow, after about a minute he reassured himself that the pavement, after those few insane twitches, had reverted to smoothness.

Thoughtfully he stood and watched the float pass him at walking speed. Then he decided to follow it.

For one cheerful thought was sparked by the very presence of the seyyo: a tradition was being faithfully observed and, to that extent at least, the Weigher was not having things all his own way. The more celebratory customs survived, the better. It suggesed that the good old institutions of Olhoav were sufficiently robust and deep-rooted, that Dempelath could not bypass or dispense with them. Not yet, anyhow.

The view widened, as the float swung out of the alley and rolled onto a section of Rullud Avenue.

Hereabouts that avenue formed a local boundary, the Occoz-Jihom border, which meant that the Noad, as he followed, had the district of Occoz on his left and that of Jihom on his right.

A sprinkling of the populace of each area had turned out to line the sidewalks, and some of these folk kept step along with their ruler. The scene would have "smelled" perfect if only these celebrants had been greater in number. Also, if they had been rather less subdued; they hadn't exactly gone glum but if they had cheered more he might have been able to trust that things were as they ought to be...

No, don't trust, the Noad advised himself. But grab what good there is.

He was not warned by any preliminary sound, when of a sudden the air on one side of him was sliced by a windy hiss. A fifty-yard-long glassite pane thrust up alongside him.

3

The pane rose within seconds to its full fifty-yard height. Towering squarely, it severed its side of the way from the structures of Jihom beyond.

During the same drastic moments an identical barrier shot up on the avenue's other side. This one blocked off the adjacent structures of Occoz.

And with dwindling staccato lisps more distant panes shot into place on both sides, swish swish swish down a further and further length of perspective, to transform Rullud Avenue into a closed canyon lined by glassite walls.

If this had happened at a more normal time the Noad would have assumed that it was a drill. Calm weather had been reported for several days, with no gneh-ou within three hundred miles, and, during such a lull, the defence against that species of malevolent cloud - a defence that consisted primarily of internal barriers which channelled the clouds' fury so that they roared harmlessly through Olhoav - need only be erected for practice drills.

Today, then, might be a day for a drill. Barlayn hoped that this was the explanation for what had just occurred, but as things were he was unsure how far to trust to his own logic. Whatever the case, he ought to do what the others who'd been caught out in the open stretch were doing. That is, get off the Avenue, fast! Only - hmm, what was this? Folk were tugging in vain at the exit notches on the Jihom side. The faint hand-grips in the glassite barrier, which should swing out into apertures for escape, appeared to be sealed.

"They aren't opening! None of them are opening!" cried a woman close to him; "Noad B-L, what do we do?" Glaring wildly, she answered her own question, "Try the other side!" For if this were not a cloud-defence drill but a reaction to a real, unforecasted attack, then the last place anyone should wish to be would be here in the glass canyon...

Barlayn turned and saw, with infinite relief, that the pedestrians on the Occoz side were having better luck. Those exit-doors were not fastened - thank the skies. They were being wrenched open by the people who had already been strolling on that side and also by those who now surged across in rebound from the Jihom barrier. So the malfunction, or the malevolence, was only in the Jihom direction.

One of the last pedestrians to exit through the Occoz panes turned to look back and saw that the Noad, apparently lost in brooding thought and oblivious of risk, still stood in mid-avenue, gazing across the newly bared vista of metal surface; so the citizen shouted at the grey-cloaked figure: "Get out of the open, Noad B-L!"

"In a moment," Barlayn Lamiroth shouted back.

He was intrigued by the fact that Smevedem's

"Welcome the New Daon" float had been strangely unaffected by the

panic and commotion. It had not ceased to trundle on its steady way, while Rullud Avenue emptied around it. And still the tubby vehicle was continuing to recede as though nothing unusual had happened. Such exaggerated tranquility was a wrongness, Barlayn knew. Admittedly, he himself was apt to set a high value on not being hurried while he sized up a scene. Well, something about all this demanded a pause for reflection. As surely as renl ever demanded that he listen to the message of a street-view, he had better attune to this one.

Within moments, his attention earned its reward from some way off. A sly, ripply thing introduced itself behind a fifth-floor bay window which obtruded some hundred yards further down the avenue on the Jihom side. For a few moments the apparition merely amounted to fuzzy motions of coloured light. Then it partially de-blurred, assuming the form of a swollen human head. Apparently someone who was almost but not quite too large to be human, was standing at that window.

Barlayn's instinct told him what to do: investigate close-up without delay. He had been expecting confrontation and this might well be it. The battle of wits which he must not shirk, could now be at hand.

However, if he aimed to collar the thing he would have to go a long way round, since all vehicular and pedestrian access had been blocked off on this side of Jihom District. Therefore, rather than that, or at lease before he did that, he had best climb to some equally high-placed window on the Occoz size, from which he could "face the Face" across the avenue.

Then he'd be able to stare at the starer and see who blinked first...

Yes, that would be the quicker and the safer opening move, though even merely doing that much he might be still be heading into some kind of trap. The thought did not deter him, for Uranian rulers - the Noads or "foci" of their cities - are confident people; without being rash they are nevertheless boldly convinced of their own ability to steer lremdly through a crisis.

Even so (one might add) their public smoothness often appears grainy to their private selves, since they see it under a private magnification which blows up the flecks of hunch and doubt. But this, if you're a Noad, only makes you more opportunistically keen, while the going is good, to push success for all its worth, to enjoy a winning streak right up to when it ends with a crash against some slab of defeat.

Here and now, Barlayn could tell that he had gained credit with his people by his visibly calm response to the glass barriers. Momentary credit might mean momentary extra power, for use against the target which fate had just handed him in the form of that glowing face in the bay window.

Despite, therefore, a horrid inkling that the thing was waiting for him, he would head that way; and moreover, since this was a war of allegiance, he would recruit some bystanders.

He strode to the Occoz avenue-edge; someone hurriedly held open the nearest glass door and he nodded thanks, went through... to find himself amongst a knot of backgrounders on the sidewalk. To a score of respectful stares he announced: "What's happened may look like a regular gneh-ou defence drill, but I'm sure it is not."

A young man duly asked, "Does that mean, Noad B-L, that you can tell us what it is?"

"It is action by the rebel, Dempelath."

Murmurs of "What?" and "Why?" formed the reactions to that.

Barlayn raised his voice and continued: "These glassy walls are suggestive, are they not? Our enemy appears to be fortifying himself beyond a barrier. Evidently he knows he's not strong enough to take over our entire city. Consequently, he plumps for a part of it only. That's an admission that he's a loser! However, we aren't simply going to wait for his movement to collapse; we're first going to make him more nervous still."

He got the more positive murmurs he wanted from this. His next step must be to make committed companions out of this cluster of folk, most of whom he knew by name.

4

The one who had held the glass door open for him was an eyabon ["restaurateur"], name of Gstatt. An elderly man, Gstatt was portly in Uranian terms, though he would have cut a fine enough figure on Earth. He belonged to that high-grade-backgrounder class (Smevedem the float-rider being another exemplar) which has been called the backbone of the

body politic.

On the other hand Barlayn Lamiroth was less pleased to note the presence of the lone foregrounder in the bunch: Bizzid Folomm, a smart young woman, but a character whom the Noad in the present instance could have done without.

We translators are compelled to be unfair. It's a recurrent problem in our interplanetary story-telling: the necessity to "bad down" our Uranian characters, to shrink their mental and moral stature by a scale factor that will render them comprehensible to a Terran audience. If we don't do that, you are apt to find them so greatly beyond you that you can't relate to them at all.

With apologies to Bizzid, then, we have to record that the Noad viewed her as a silly woman.

This brassy-blonde alapatea [think

"anecdotalist-socialite-poet-reporter"] was, by Barlayn's standards, an airhead. Ordinarily he would have shrugged this off with equanimity. He indeed shrugged now, but without the equanimity. He could really have done without Bizzid, right now when a serious enemy loomed.

His companions were being affected by the apparition that glowed in the fifth-floor bay window a hundred yards down the street. The sight, with its mysterious threat of direness, was close enough to appall yet far enough to blur amid creepy doubts.

Gstatt quavered, "Noad, that thing - "

"We're going to see it up close," said Barlayn. "We're going to 'open the envelope'."

By employing that figure of speech, which we Uranians use for 'to make the unknown known', he aimed to inspire their natural eagerness for action. A springiness was what he hoped to see. Not the drooping shoulders that, sadly, he did see. Had these folk been sapped by events? Did the ordinary citizens of Olhoav lacked the resilience of yore?

Perhaps they do, and yet I must continue to believe in my people.

"Our foe," he continued dryly, "calls himself - as you may have heard - the Weigher." Saying this with quirked lip, the Noad still hoped for some flippant snickers in response. He wanted to hear them scoff at the rebel's pretentious title. He did get of the reaction for which he hoped: a few smirks. However, most of his audience stayed too quiet and unresponsive. The dismal suspicion, that their loyalty could not be taken totally for granted, grew in him. He had to say more. "It's time," he shrugged, "that we did some 'Weighing' for ourselves. Those who are free of other tasks: come with me, please, to the fifth floor of - " he looked up to determine which of the buildings on this side was exactly opposite the Face on the Jihom side - "the Oxpeihon. Yes! We'll head for the Oxpeihon. Let's take Fate by surprise: let's run."

He turned to lead the way at a hastening trot before they could have second thoughts. And - they followed. Well, that was something.

If they had not follwed, what then? He could hardly afford to think about that. He had had no "Plan B", as you Terrans say.

Yet he must consider that Dempelath's propaganda might have made inroads among them. Well, if they're discontented backgrounders, the Noad snappily reflected, if they crave the spotlight, they ought to welcome the prominence I'm giving them now...

Upon reaching the Oxpeihon he hurtled through its lobby and began to mount its stairs, his followers clattering up behind him. They were, he hoped, drawn by the powerful, deep-seated loyalty of citizens to their Noad. Aware that Fate had given him support of average quality, from which he had better not expect miracles of devotion at this dubious time, the Noad at each bend of the staircase glanced back to assure himself that he still led the group of men and women whom chance had appointed to swirl in his wake, be they backgrounders or foregrounders; whichever - they were all Olhoavans, for goodness' sake...

Actually the whole "background-foreground" distinction roused doubts in him at moments like this. For example, Gstatt was regarded as a backgrounder, Bizzid a foregrounder, but the solidity, the moral heft of the one compared to the other, suggested how misleading those categories were...

Never mind - the issue faded away as he told himself that they might all be rushing on a fool's errand if the Glowing Face was not still visible by the time they reached the fifth floor window.

But no, it was more than a safe bet, it was a million little bursts of insight, shouting in summation that their target would be waiting for them.

Ascending the last steps to the fifth level, the Noad saw how right he'd been not to worry about an anti-climax.

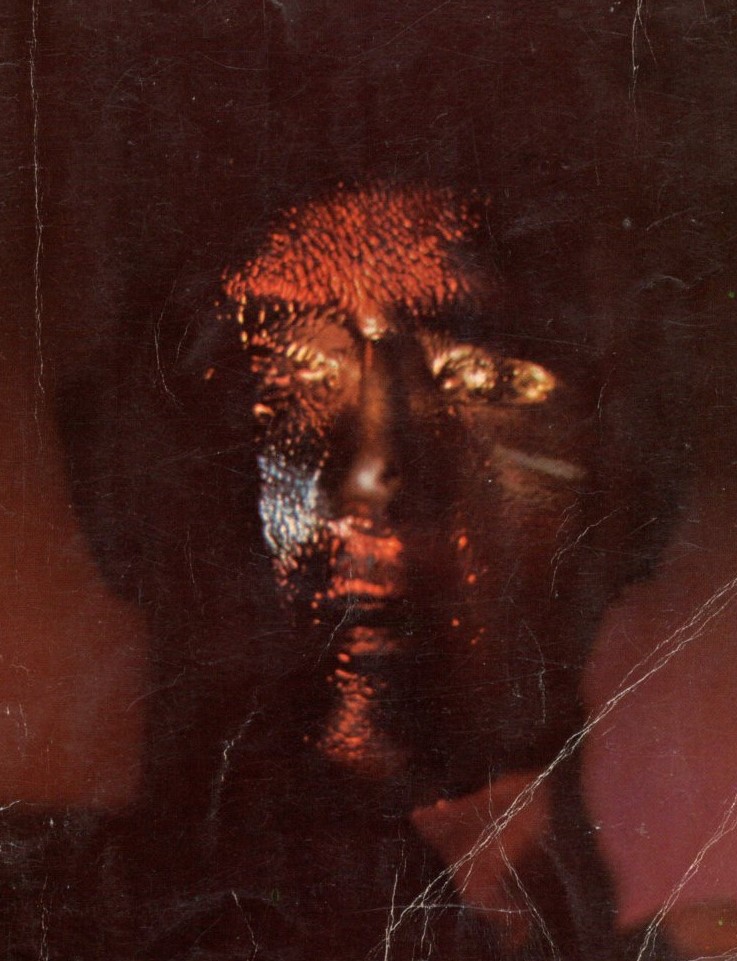

Dempelath behind the panes

Dempelath behind the panes The fifth floor was wide, and its furniture scant. Open-plan spaces were the rule up here. Barlayn started forward, intending to lead his little crowd towards the out-thrust bay window. Each step, however, became a drag against a weight of reluctance, as the motions of his body were inhibited by the Face that now directly shone through that window from across the way.

Besides his own dragging steps the Noad could sense behind him the equally gluey manner in which the others shuffled.

The voice of Gstatt rasped, creditably, "We'll out-stare him, Noad B-L." But no one else said anything.

Barlayn realized his mistake in bringing so many witnesses with him. As he glanced over his shoulder he noted with sad disappointment, from their darting, evasive eyes, that they simply weren't up to seeing that Thing out there.

5

Gstatt was the best of his supporters in this pinch. As the Noad well knew, the restaurateur had in his younger days accumulated a Wayfaring record such as none but the brave can earn. Yet he looked ill at ease now; so much so that the Noad, looking at him, could not but wonder: "if even this stalwart fellow looks almost as edgy as the rest of this bunch, might I not have an error of judgement in bringing them here to be locked into a staring match with the Face?"

Always a bad idea to be locked...

The main risk, he guessed, was that this "Weigher" might arrange for them all to be taken in some sort of flank attack while they were practically immobilised by the sense of strangeness and dismay which seeemd to be taking hold. Why, though, was it working this way? Why was the sight of that Face with its crawling lights so awful? Barlayn forced himself to stare analytically at the thing. The

apparent distension of that luminous head: it must, no doubt, be an optical

illusion, a merely apparent swelling, caused by the coloured glows which swam across it - or was that too glib? Barlayn had sudden doubts about his own excuse-grabbing wits.

The disquieted Noad needed plenty

of spunk to get him through the next quarter of a minute; his inner

defences swayed, teetered, but fortunately did not all collapse simultaneously. He was able to steady himself with one philosophic prop after another, all variations on the theme which underpins Uranian life, namely, the precept that wisely insists that you do not need and should not expect to understand.

- But really, come, this childish staring-contest was ridiculous! Here they all were, goggling, eyes locked with the Face and neither It nor he, the Noad, being able to afford to be the first to look aside - come on, this was the wrong game to play! We'll out-stare him, Gstatt had just said, but there must be more to it; some practical blow was surely being prepared. It stood to reason that Dempelath must even now be arranging for some flanking movement or other. After all, that was what the Noad himself would have done, in this case by giving instructions to Dynoom - he'd have done it by now, were it not that this room happened to lack any line of communication with the city-brain. Flunnd, what a blaping misfortune. If only this were a room fitted with Ghepion connections. Of course, Dynoom could project nenself anywhere in the city but, as bad luck would have it, Barlayn could not contact the Brain from here on his own initiative.

One of the crowd behind him dared to interrupt his thoughts, pleading, "Perhaps we ought to... er... postpone all this, Noad B-L."

Those words made him realize: only a few seconds had passed. Time apparently had slowed almost to a stop.

Barlayn, struggling for breath, replied: "You mustn't miss this great moment." He made his tone cutting and dry: "Behold the shining form of the great Weigher himself; Dempelath, and none other. I know it is he, because, of course, the great man would not permit such dominance to anyone else. Now, did I hear someone say 'postpone'? Sorry, can't avoid the clash. But postpone the understanding, yes by all means! Let's make sure we beat him first, and then, if you're still keen on understanding what's wrong with his skin..."

He intended to say, "When the trouble's safely over, anyone who wants to muck around for an explanation for those swimming glow-patches... anyone that dedicated can spend time and attention on it for all I care. I'll have better things to do."

He felt, for a moment, like a pilot who had successfully skimmed between fangs of rock. Then, to his exasperation, that woman Bizzid Folomm had to put in her phial's worth:

"If we're going to beat him, shouldn't we find out what's wrong with him?" she demanded brightly.

"Why?" responded the Noad, in the hope that one flat syllable would discourage her.

"Normal people don't look like that. And normal people don't raise rebellions."

Barlayn hung his head. The woman had defeated him. Steer... a Noad must know how to steer. Make decisions from insufficient data, then abandon those decisions in the face of further insufficient data... on and on, to weave around the waves. But he'd have to be quick now. It was needful to bring stuff into the realm of the bearable, the explicable, instantly; Bizzid was right so far, no matter what theory might say. For those shining lobate patches of glowing colour which swam over the skin of Dempelath in eerie uneven motions did, after all, require an acceptable explanation. Some stuff was so outrageous you had to find answers for it, to avoid a shriek of the mind. Allowing his opinion to swing about, Barlayn took up and wielded the mental spade. Explain, describe and thus belittle the enemy's power.

So the Noad silently beseeched the World Spirit to help him, or at least, he sought to fire his own will and simultaneously to invoke the sympathy of the World Spirit. But instead of relief, a further offensive event just then became visible.

This new outrage was from a long way beyond the Face, in some distant street along the same line of sight: the indecently rapid sprouting of a spike of gleaming metal. Was the city's fabric itself going mad moment by moment?

6

It's time for another of our corrections. This latest necessary amendment, of an impression we have most likely made on the minds of our Terran readers, concerns the word "avenue". When we use it, you probably picture a wide street lined by block-like buildings. Indeed, some lower reaches of Rullud Avenue are like that, and for that matter any radial road in a Uranian city is apt to attract quite a few square-fronted edifices, a practical way to maximize the use of available space. However, if you look higher than the third or fifth storey, your view changes, the rectangles are over-bulged, and our irregular urban lattice takes over.

Therefore the vista from the fifth floor of the Oxpeihon was no mere line of rooftops but a metalloid jungle of weblike walkways, globular palaces and helical towers, looming and arching over the avenue; and what the Noad witnessed in that eerie moment could have been a mere addition to that tangle of shapes. It was not the form but the speed of the new spiky tower that shocked him. Huge and distant, visibly pushing up beyond the architecture of Jihom District, beyond even the landmark dome called the Menestegon which lay in the same line of sight, it grew with a speed that was abhorrent. It was pushing up by the second! Gazing at it, Barlayn could almost imagine he was watching a time-lapse film of the growth, not of a man-built tower, but of a giant vegetable stem bearing sickle-shaped leaves.

His eyes then had to snap back to focus upon a closer event, for a change was coming over Dempelath's face. Several of the crawling lights on the Weigher's skin had coalesced, now forming a yellow dagger-pattern which flowed from chin to forehead. Shortly this new pattern in turn dissolved, back into the previous medley of colours and forms... but the Noad had seen enough: understanding had come: the answer for which he had prayed.

"He's a hybrid monster," Barlayn Lamiroth remarked aloud. "Part-man, part-Ghepion! He displays on his skin - the poor fellow can't help it - his resonances with the physical networks of the city." Great was the satisfaction which the Noad felt for having formulated a statement that was not only neat but probably true: for those swirling glows on the Weigher's face most likely did signify direct power-connections between the would-be tyrant and the infrastructure of Olhoav. Thus more than coincidentally, the dagger-pattern resonated with the appearance of the spiky tower. Yes, it put was good to have found something to say, it put a spring in his spirit that an insight had loosened his tongue, but the implications were frightful. Whatever that spiky tower might turn out to be, the scariest thing about it was that expenditure of energy to produce it must have devoured a chunk of the reserves of Olhoav.

Someone else in his group whispered, "But why is the face just standing there, staring at us?"

"Trying to out-stare," replied the Noad, and fluently continued, "Rebels are necessarily boastful; they must compensate for their lack of legitimacy. Look at him gloating at us from behind his wall and trying to say: 'Today, Jihom; tomorrow, the city entire' - thus assuming that time is on his side. Whereas," Barlayn went on, glancing around at his audience, "Time, as our enemy has yet to realize, is a public utility."

Hesitant chuckles. Doubtful looks...

He swung round again to confront the baleful glow of the visage across the avenue. He reckoned it should be easier, now, to get out of the staring contest. Honour was satisfied insofar as he, the Noad, had spoken wisdom to his people... had "kept his end up" as you Terrans would say.

A raspy whisper, like wind-blown tin fragments, sounded in his ear. "You wished for news of Dempelath."

No mistaking that confidential projection.

Irritated, yet appreciative, the Noad murmured back, "I did ask, yes, but now I have found him myself, Dynoom. Like you predicted I would, in fact."

"Nevertheless may I show you my own finding?"

"Go ahead," said Barlayn, adding more loudly and with calculated recklessness, "and since I'm out on this limb, you may as well make it public." He addressed the company: "Stand back: we're about to see a holo-report from Dynoom."

Obediently, his followers with fast backward steps cleared the necessary floor space. The group's attention was immediately focused on it.

A pale mound of light appeared like the top of a ghostly sphere rising out of the floor. It sifted into a sharp, cinematic rendering of a city scene: quite a nearby scene, perhaps a few hundreds of yards away, where the blue float, with its celebratory banner welcoming the new Daon, still moved at walking speed down the deserted avenue, towards the woman it meant to honour.

7

...Or, the not-quite-deserted avenue.

Some barrier doors on the Jihom side were now being opened. From within Jihom, apparently. A few folk who had been shut away inside that district were now venturing onto the avenue floor.

Gaining confidence, others followed. Increasing numbers streamed to get in the way of the float. They must be so pleased to see it, their enthusiasm was impeding it, causing it to roll to a stop. No, actually - thought the Noad as he watched - it wasn't so much the float that interested them, enwrapped though it was by the press of people; rather, what attracted the crowd was another, convergent arrival. It was the Daon herself, it was Sunwa Nerren, causing all eyes to switch to her as she strolled into view out of an alley on the Occoz side.

With gracious gestures she hailed them all: the folk who had surged around the blue vehicle and the original riders upon it. She opened wide her arms, as if to accept anything that they might ask of her, any pleas, any questions, any demands.

The watching Noad meanwhile had his own plea: allow me to be glad of the job I pushed her into. Let there be no reason why this should not turn out to be a fine, normal, meet-the-Daon public session as is traditional in sane times. And why not? The crowd seemed sincerely eager; folk at the back were straining to glimpse the Daon, yet a decent restraint was evident.

A voice of greeting resonated from the float's prow. "Skimmjard, Daon S-N!" the seated rider called down at her from his vantage.

This caused some heads to turn from the Daon back to the float - to the individual whose voice had just boomed and whose eyes were fixed intently upon the blue-cloaked woman as her steps took her closer to him. No one else spoke. He continued: "Tell us, Daon

S-N: all those times when you were stuck in your Wayfaring routine, did you not dream of this day?"

With each second that ticked by it became more evident that he, Smevedem, had a kind of priority in the role of interrogator. Daon Sunwa Nerren took no umbrage at this. She chuckled, "You mean, is this the fulfilment of my dreams?"

"Ah, so vital it is to have dreams! Didn't you always trust," Smevedem continued with rising intensity, " - that you would amount in the end to more than mere fodder for the cartographers' stats? Was it not essential for you to believe that to be fodder was not your role; that you would not remain in obscurity for the rest of your life; that would become the privileged super-forg you now are?"

The words now were roared more harshly; the listening Noad's heart sank as he recognized that backgrounder resentment was being starkly, albeit tortuously expressed. What of the Daon's reaction? Suresly she must have caught the hostility; yet her face was showing no strain.

She simply agreed, "I most certainly did always hope for more."

That sweet reply appeared to win hearts in the crowd; admiring eyes turned back to her.

She continued, "And my hope was granted daily." Her voice rang lyrically pure; the audience straightaway sensed that they were about to hear a shining conclusion. They froze, mid-breath, as she went on: "For my old profession of Wayfaring, like every calling, is more than itself. Every one of us - be nen the most obscure of wirrips or the most famous of Sunnoads - equally feed the cosmic statistics, that grand summation which, over the history of the universe, will welcome every life."

Surely, thought the Noad with admiration, she has done it. How could backgrounder resentment prevail against this wonderful vision of wholeness and peace?

"No act wasted," concluded Sunwa, "no life lived in vain, wirrips or forgs, and, if fodder is the right word, essential fodder we all are."

The crowd were utterly captivated. The speech's aura of perfection made all those present feel as if they could have gone on listening for hours, and indeed Barlayn and his group, watching Dynoom's live holograph of the event on their upper floor in the Oxpeihon, felt the same.

The float then began to shake. Because the vehicle was tightly surrounded by people whose attention had been drawn away from it, its sudden movement shocked them. The spell of Sunwa's words was broken. Some listeners staggered; some were knocked over.

We do not relish this part of our tale...

8

It is one of those rare occasions when we almost envy the Terran simplicity of soul. It is a simplicity denied to us Uranians, for on one momentously dire occasion in our distant past we sinned in a manner never to be forgotten, inflicting deep damage to a cosmos which had done us no harm, and thus self-harming beyond the capacity of lesser or retarded folk.

Why cannot we "move on"? It is because our culture, our identity has sprung from what we did in the early morning of our history. The wealth and power of the Phosphorus Era - much of which has been transmitted down the subsequent ages - was gained at a terrible moral price. You men of Earth may lament the environmental damage caused by your predecessors, but you don't have to feel guilty about the plunder of an entire universe! When we sucked the energy of Chelth for our own use, we committed a crime for which there is no atonement. That door is now closed, and ever since then we have had to live with what we have done.

Usually we manage to cope with our consciences. After all, the plunder of Chelth happened scores of eras, thousands of lifetimes ago.

Yet on the occasions, since then, that we come up against manifestations of the murkier laws of physics, we are apt to get queasy. Any peculiar phenomenon may provide us with an unwelcome reminder of what our long-gone ancestors did.

9

The people in the vicinity of the float could not understand, but they could run, and did. Small wonder that they scattered: the vehicle had shaken like a fever-maddened living creature and it had hit several people at chest level.

Watching the image of these events from his vantage, Noad Barlayn Lamiroth meanwhile nodded to himself grimly. He knew better than these folk who in their panic and ignorance could not be expected to understand anything at all about what had hit them. Admittedly he had no evidence, but his integrative faculty swiftly linked what he saw to the other recent appalling surprise: the growth-spurt of the distant tower.

His hunch became stronger when the retreat of the crowd revealed the bit of city-floor beneath the float. That portion of the metal avenue was quivering. As the Noad watched, it rose in a sort of viscous spiral.

This latest growth slithered plastically around the float, and up its sides, to obscure it and then completely to cover it. Next came a sucking, tearing sound as the new covering, with the vehicle enwrapped, detached itself from the avenue floor and began to roll. Apparently the float had become an armoured vehicle.

The sheer strangeness, the nightmare incongruity of this metamorphosis kept the crowd fleeing further, some of them shrieking as they glanced back. None of them were likely to possess the melancholy comfort available to the Noad, who from his store of city-lore had identified the means used: the local acceleration of time, the sort employed on a few historical occasions to squash a long feat of engineering into a few seconds. Fantastically expensive, so much so that it need not be feared often. Still, he wished it had never been done at all. It annihilated the normal everyday trust which one feels for one's built environment. It mocked one's intellect with shady physics. Run, the Noad prayed at Sunwa. Ghepion science is at work.

Yet how could she run after she had made that wonderful concluding speech?

Then came the hurled spear of light. It was impossible to say from which individual the shot came: Smevedem and the other riders on the float were now hidden beneath the vehicle's armour, and all that could be seen was the sudden hole in the prow and the beam that lanced forth from it.

After it cut the Daon down, the wails of the crowd and the crunch of the retreating wheels were all that remained for the city's ruler to hear - that and the despairing thump of his own heart. Of those around him in the Oxpeihon, none spoke. Were they waiting for him to pronounce some plan? Probably not, at this moment; they, like he, were stunned.

The loss was so dreadful that the Noad had scant need to ponder its consequences: starkly obvious it was, that the balance of power had shifted away from the civilization he knew. Two successive Daons murdered within hours of one another: as clear as could be, the message was that the appointment of a third would merely set up a third victim. That pointless step he would not take. Thus henceforth he must remain without an heir. His own single life was now all that stood in the way of political chaos.

Even that was probably too cheerful a summation. Worse things than chaos may exist. Whether he lived or died, time was on the side of the Weigher. In fact, that title "Weigher" was, Barlayn now saw, more appropriate than he had previously realized: it aimed to outweigh that of 'Noad'.

...Across the avenue, the face of Dempelath began to shift at last.

While its garish lights continued to crawl across cheek and jaw, the head rotated to appear in profile, as the hybrid creature began to walk towards the exit from that room whence he had stared...

Dempelath disappeared from view.

I get the point, Weigher, muttered Barlayn. Your proxy deed is done. You could not have killed Sunwa personally, for I was watching you all the time. The shot came from the float and not from you. Perhaps you did not kill Dari either. You don't have to do all your own dirty work. You have an effective following. A murderous army of biddable backgrounders is ready to oblige you.

The unstoppable onset of a dark age seemed to threaten the city, and yet, though lacking a plan or rational hope, Barlayn Lamiroth was simply not capable of envisaging defeat.

CONTINUED IN

Uranian Throne Episode 7: