uranian throne - episode twelve

the city cracks

by

robert gibson

[For the story so far, see: 1: Dynoom; 2: Hyala; 3: the nebulee; 4: Exception; 5: the lever of power; 6: the infrastructure throbs; 7: the claw extends; 8: the brain-mist writhes; 9: the last card; 10: the londoner; 11: the terran heir]

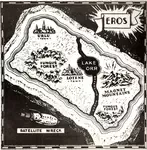

[ + links to: Glossary - Index of proper names - Timeline - Survey of Ooranye -

Plan of Olhoav - guide to published stories ]

1

Terran

readers, in this your forty-second century, please keep in mind

that the rise and sway of Dempelath took place two dozen lifetimes ago.

Remember therefore that the story we're telling you is not

what you would call recent; its events occurred

long before the men of your planet had begun to communicate with ours. In itself, such antiquity is nothing special. Indeed most of the tales which we transmit to you took place in periods far more ancient still. Compared, say, to the epics of Restiprak Zentonan or of Taldis Norkoten, which vastly pre-date the rise of civilization on Earth, our present narrative is relatively modern.

However, what makes the Dempelath saga unique is that it features one of you. The tyrant's great opponent was a man possessed of a Terran consciousness, the only Earthling ever to gain direct experience of Ooranye before our present era.

Actually we're

apologizing here for our inability to resist the temptation of

hindsight: which is bound to affect our narrative of Neville Yeadon / Nyav Yuhlm. What we didn't know about you Terrans in those days, we do know

now. Looking back across that minor gulf (a couple of your millennia amounts to a much more impressive stretch of time for you than it does for us) we find ourselves ablaze with compassion, for as historytellers we are shocked by the pitiful culture of Earth in which "fiction" and "history" are different things.

Here it is certainly not so! Here, none of us had ever entertained the notion of "pure fiction" before radio-contact with your world brought the peculiar idea to our notice, and to this day we do not "make up" any of the narratives with which our literature is adorned. Though we have learned to enjoy your inventions, we ourselves have no need to write in your "creative" mode because on our world the currents of fate are inherently creative. In other words, real-life events on Ooranye naturally fall into an artistic pattern. Therefore our tales are all true; artistically told, to be sure, but true; and Uranian story-telling and Uranian history are one and the same.

A far cry from the situation on Earth! Forgive this blunt statement: your histories are often plotted so ineptly, that a dismal gulf yawns between their accuracy and their narrative trim.

Do you require an example? Zoom in, if you will, on your year 1471.

The scene: England during the Wars of the Roses. Intrigue, betrayal, dynastic conflict. The over-mighty earl of Warwick, the "Kingmaker", had changed sides from York to Lancaster the year before, restoring Henry the Sixth to the throne. During the months since then, however, the ousted Yorkist King Edward the Fourth has returned to the country and is gathering his forces. Warwick's former enemy Margaret of Anjou, with her son (Henry's heir), ought to pitch in to help stave off Edward's comeback, but she delays out of mistrust of the Kingmaker. Profiting from their disunity, their common enemy advances and, in a great battle at Barnet, Warwick is defeated and killed...

Now spare a thought for Bulwer-Lytton, author of The Last of the Barons. It's a great

book, but, through no fault of the author, it suffers from history's poor plotting. A much more satisfying climax to the tale could have been achieved by placing the defeat and fall of the Kingmaker as the last act in the drama, with Edward of York closing in on him after having defeated the tardy and mistrustful Margaret at the Battle of Tewkesbury. Unfortunately, history made a mess of the sequence: Tewkesbury occurred after Barnet. You see what we mean about the shape being wrong? Anti-climacterically, the final defeat of the House of Lancaster occurred after the Kingmaker was already slain.

Your World War Two is similarly skewed. Axis tail-enders Japan continued to fight for three months after the Third Reich had met its doom. No writer, given the choice, would opt to structure an epic so lopsidedly; but the option of a properly streamlined fate, more often than not, is simply unavailable on your planet.

The challenge is to explain why your history is so artistically inept. What is the reason for such difference between the third planet and the seventh?

We will offer you an analogy in physics, one which illuminates both what we have in common and wherein we differ.

Brute cause-and-effect chains, like the powerful ionic bonds that bind atoms to form molecules - they exist with us as they exist with you. Here on Ooranye, though, life-stories must also submit to a higher steering. This is a force which does not bind short-range, but can be likened more to the diffuse, elastic, inter-molecular attractions that give surface tension to a liquid. Call it destiny if you wish; or call it reality's plot; in terms of fate-trajectory it's a morphic current inclined to shape the flow of events into those aesthetic proportions to which a Terran fiction-writer will make his story adhere, if he can.

If he can! Bulwer-Lytton remained faithful to recorded history, and paid the artistic price. While we sympathise with his constraint, we may also hear the whisper of our own doubt: is it possible that conditions on our world also bring their own restrictions? Is there a mode in which we are the unfortunate ones? Be that as it may, we ask you to remember the gulf across which you gaze,

when you read of the destiny of Neville Yeadon alias Nyav Yuhlm.

2

Ooranye

is a world without "time-zones". Kindled planet-wide, the globally

simultaneous morning bioluminescence began steadily to intensify as if in response to the smooth twirl of a dial, gently brightening the air all around our globe. Thus was the regular light-curve traced by the diurnal sine-wave of microscopic throom during the early hours of Day 10,538,685 of the Actinium Era.

In

the city of Olhoav the airlight of the new day seeped impartially into

dwellings rich and poor, through the crystalline windows of globular

palaces and the canvassy skins of humble bafracts,

to play upon foregrounder and backgrounder alike. Fuzzy lobes of this natural illumination, compensating for the scarcity of lamp-fuel under

Dempelath's regime, reached round every corner to reveal the most

obscure crannies in the city.

In one of these undistinguished architectural folds, a youngster named Lanok Ryr opened his eyes.

Having slept fully dressed, as we Uranians frequently do, he lay blanketed by the coarse fibre of a snoobagog, a blanket woven from the imported leaves of an oyor, a giant-grass forest.

Before he made any move to rise, he listened. What he heard, or rather

failed to hear, gave him pause. His home, in one of the numerous

bafracts around Flexion Five on the Choot Skimway in the district of

Occoz, was normally pervaded with a buzzing murmur of traffic, but now it

was quieter than usual.

His

first thought, from the coldness and dimness of the

air, was that it could not yet be the third hour. That would explain the

surprising quietness. He had expected to sleep longer, because he had

worked late last night. What could have woken him? A bad dream?

Perhaps the type of dream one has to wrench onself out of -

Or,

far worse, could it be that the "wrench" was part of the dream and that

the dream was not yet over? His mind groggy and dank, with unease feeding the fungi of suspicion, he opted for harshness: he

made a fist and hit himself on the ear.

Pain, sharp, immediate, gave

proof enough that he was awake. So then - he had been roused by

something real. Perhaps a clash of arms or an explosion, followed by the silence

of death?

Occoz

was normally a humdrum district. It had submitted in practice to the

Weigher, while remaining loyal in sentiment to the Noad. On the

lines of this compromise, the peace was usually kept. However, no part

of the city could be immune to civil unrest, given the revolutionary

disturbances of the past two hundred days, and he'd better try and find out whether something was going on.

The

young man rose and peered around the partitions of his dwelling. A few

quick glances confirmed that he was alone. His mother had risen

already and left for her work. His father had been killed 1800 days ago

on a Wayfaring trip. He had nobody else.

Ah, well, now that he was up he might as well get on with his day - but wait, what was this stuff on the floor?

Fragments

of an ornament: the ceramic twigs of a phial-stand, one of his mother's

scant collection, now fallen from its shelf and smashed.

That

could not have happened by itself. He thought back to his dream.

Though the details were dissolved away, there lingered the remembered

sense of some motion with a bad "flavour" to it. Some sort of billowing of his home's flimsy walls...

Deciding to have a look outside at once, he stepped through the main

flap, onto the platform edge, and, from the airy perch of his lofty

bafract, he looked around and down.

Residents of the Skimway's upper environs must necessarily have good heads for heights. Lanok therefore was not at all bothered that his lines of sight shot down through a quarter-mile of latticed swirls and threaded palaces towards the city floor. At half that distance, though, an odd spatter of motionless forms did cause him some unease, for the shapes had to be bodies, strewn on the Tnoff Skimway, the next big ribbon down from the Choot.

From an entirely different direction - to one side and slightly above - his attention was diverted by a scraping creak. He gazed about and spotted a goods-pipe that had just begun to collapse. Aghast he watched it sag and slither down the side of its adjacent tower. Something, he realized, has shaken and weakened this part of the city.

In several other directions, dots that were human figures crawled with wary slowness. Some of Lanok's neighbours could be seen gesticulating on platforms in the middle distance. Then he noticed a cloaked climber below, who at that moment looked up at him. The man raised an arm in a gesture that certainly meant, stay there, I am coming to see you.

Recognition of this person's face - it was none other than the City Surveyor, Nuth Geven, who was ascending towards him - altered the outlook for Lanok Ryr, kicking other options for consultation out of his mind. The helmeted Surveyor, pulling himself upwards with elbows spread, was suggestive of a burly bead sliding along a purposeful wire.

With a final spring the Surveyor reached the startled youngster's own platform and said, "Will you accompany me to the Menestegon? I require a witness for my report to the Weigher."

"I was asleep - " began Lanok, not wishing to mislead his boss.

"I don't mean a witness to the quake; I mean a witness to the truth I'm going to tell him. You'll do, I reckon."

"If no one else..."

"I'd rather not spend time looking for anyone else. Ready?"

"Yes, sponndar."

"Then follow me," commanded the Surveyor and set off along a walkway in the direction of Jihom District.

3

Obediently trotting after the foregrounder, Lanok inquired: "Sponndar N-G, you said 'quake'. Is it over?"

"I fear not. What we have experienced is the prologue, the harbinger. Olhoav has trembled but has not split. Worse is likely to ensue. It may culminate in... let's call it the Cracker."

While they made their way downwards along the reticulations of the walkway network Lanok eyed the various junctions where stores and tools were kept and which, on a normal day, he would visit in turn to check them over. His glances flicked at one indicator-board after another, out of habit alone; a mental legacy from the old work-trance which used to characterise all regular employment. Though his activities as a city-maintenance operative were nowadays undertaken fully awake, task-selection remained largely instinctive, so that he never hesitated as to priorities... on a normal day. But this morning he was being required to do something quite beyond his routine. Well, it was not for him to decide; he need only obey orders.

A comforting conclusion. Lanok Ryr, despite his two names, basked in the unambitious glow of acceptance of his lot in life. This humility remained unaffected by his mother's effort (influenced by the prevailing fashion) to push his claims to a forg-style second name. She had spread the story that the squall his new-born self had uttered after his first word "Lanok" actually was that second name, and indeed it was likely enough that he had squalled "Ryyyr", but this did not alter the way he felt about himself. Therefore, like a good single-name backgrounder, he simply followed his boss and asked no

more questions -

Not even the rather good question, why Nuth Geven's impending encounter with Dempelath should require a

witness.

That thought did, admittedly, cause Lanok a certain tingle in the psychic nerve-endings. It was as though he had arrived at a point of inflexion in his life's graph, were about to don protagonist's status and get pushed onto the lit sage of story. But this was only one murmur at the back of his mind, far out-murmured by other thought-streams, the amplitude of lowliness easily swamping any higher destiny.

Meanwhile they reached a major utilities junction, where the pedestrian part of their journey came to an end. Nuth Geven stabbed twice at the console and two doors cycled open. Out slid a couple of skimmers with hulls of Maintenance red. Thence, having mounted these vehicles, the men had no more need to walk and no excuse for delay: they were able to race along the ribbon which spiraled down towards the city-floor, until they dismounted on a platform atop the last ramp down.

Here, about a hundred yards from their destination, Nuth Geven gripped the railing and gave a hiss of disgust as he gazed down at the throng which crowded the frontage of the dome-topped Menestegon.

We advise the Terran reader to picture this building as a fifty per

cent enlargement of the Royal Albert Hall, stylistically blended with an

upside-down Guggenheim Museum, and surmounted with a spiky halo of

access tubes and walkways. Its traditional role was as a library and

centre for historical studies, before the Weigher chose it

for his favourite residence and pervaded it with his power. Now it seemed a magnet for an anxious, pleading mob.

Turning to his companion Nuth Geven remarked wearily: "Suppliants! Look at them, Lanok Ryr! Subjects - abjects, more like - craving an audience as they shuffle in front of the ruler's palace. A guard at the door! Smirking at them! What is this, some kind of arelk Vanadium-era despotism?"

Shaken by this outburst from his work-boss, Lanok did his best to look with fresh eyes at the gathering below. He could think of nothing to say.

"Just look at them," the Surveyor repeated. "Can you imagine Barlayn Lamiroth ever allowing folks to bunch up like that? But perhaps you don't remember how things used to be, Lanok Ryr. So let me tell you: our rightful leader could ride the event-currents alongside his people, and converge naturally at the right place and time to see you if you needed to see him, without this crude mass-batching of business which makes any decent lremd citizen sick."

The tone demanded that Lanok respond with a staunch declaration. Effort was required; a case of pulling oneself together. "Sponndar," the youngster assured the elder, "I am 5044 days old: enough to remember, and to get your meaning about the decline of renl."

"Good, good; glad to hear it... Meanwhile, however, I suppose this may not be quite the right moment to spend lamenting days gone by. Rather, the next thing is for me to become a suppliant myself. Might as well join the fashion." Nuth Geven backed from the rail and began to stride down the ramp, and then stopped. "One point to clear up first. Tell me, lad: are you a first-lifer?"

Surprised by the question, Lanok nevertheless had no doubt of the answer. A small boy might be unsure whether he had lived a previous incarnation, but a young adult forty-four days past his majority must certainly realize, from the chalky consistency of certain memories drawn apart from the rest, that he had lived before, if such were the case; whereas he, Lanok Ryr, had no such double memory-tissue, and therefore this was definitely his first life. "Yes, sponndar."

"Glad to hear it," mused the Surveyor. "I feel justified, then, in dragging you into this. If the worst comes to the worst... you still have another one to come."

Lanok stood all the straighter for this hint of mortal danger. "First life or second, I'm not about to turn yellow," he said.

Nuth Geven laughed at the use of the alien idiom. "That turn of phrase is... cute, I believe," he remarked, showing that he, too, could absorb interplanetary lingo. (It was a widespread amusement in those days, a kind of zestful release, to use or misuse the vocabulary recorded from the night-babble of the Earth-minded Daon.) Going even further to demonstrate fashionable proficiency in the Terran tongue, he added, "So let's go and 'beard' the Weigher in his 'den'."

They started off down the ramp, towards the pentagonal promenade which fronted the Menestegon.

Approaching the edge of the "suppliant" crowd, Nuth Geven gazed over their heads. A guard stood, laser drawn, at the top of the steps in front of the building's main entrance.

"Ahah," muttered the Surveyor scornfully, "we're really condensing into hierarchies here. Notice that flunnd's arm-band."

Lanok Ryr said, "I see it." A white grey-bordered heptagon, insigne of the Glomb, marked out the guard as an extension of his master. Lanok added thoughtfully, "But you, Surveyor N-G, are an official, too."

"That's just the point I'm going to make," replied Nuth Geven as with set jaw he began to push his way through the throng.

Those who pushed back at him did so too feebly and confusedly to match his grim assurance, while others, at the sight of his helmet, helped him forward, urging the rest to stand back, for was it not a good sign on this quakey morning that the Surveyor had arrived to confer with the Glomb?

Lanok Ryr, trying his own best to look confrontationally keen, managed to shove along in the wake of his boss.

Nuth Geven emerged from the crowd's further side and made his way up the front steps of the Menestegon. The guard brandished his laser and cried, "Stand back."

"Listen, fellow," said Nuth Geven, "you know who I am and," he tapped his helmet, "you can see that I am on patrol, which means, in view of what's happened this morning, that Glomb Dempelath will wish to see me; and in order for that to happen, you must allow me through the door."

"Dempelath's orders - "

" - Won't save you, if what I have said is true."

Nuth Geven had not slackened his pace and by the time he had uttered the word "true" he was level with the guard. That unfortunate man stood paralysed at the focus of all eyes in the watching crowd, and disabled from action by his own inner agreement with what the Surveyor had said. Lanok Ryr meanwhile, mounting the last step, guessed that Nuth would not be stopped but was not certain at first whether he, too, would be able to pass. The next fraction of a second brought the answer in the form of being pulled along in the slipstream of Duty which here condensed into a line of force, a giant fast-hurled spear transfixing one's free will and hurtling past the guard, through the entrance, into the lobby - where was space for a moment of reflection.

Lanok realized that he would, in any case, have committed himself to this course, out of an almost filial loyalty to Nuth Geven. More than half of the youngster's fear was, in fact, concern for the elder. He'll get chewed up and spat out for this. We're about to "barge in" on one of Dempelath's colloquies - we ought to have waited our turn - "

Yet when they trod the carpet inside the huge, dimly circular auditorium, these fears were replaced by others.

4

Not more than a moment was permitted in which to stand and collect one's thoughts, in what felt like a lonely, empty dark hall. A whine like that of an insect droned past Lanok's ear. At the same instant he glimpsed a pink-gold spark of fuzz streak across his field of view close to his head.

Suppressing his shudders, he focused upon the middle distance. He knew, and could partly see, that in the hall's dim centre was a dais. On it must stand the podium and on that a narrow chair - from which the director of a historical epic would, in normal times, conduct the holographic presentation by "playing the wires" - the web of controls was barely visible as a silver network radiating upwards from the chair.

Faintly, some further whine or hum, or chant, from that central direction, registered on Lanok's ears.

Clustered where the podium ought to be, a pale blob of the pink-gold light seethed and dimly sparkled. From within that undulating glimmer, the outline of a seated human form gradually took shape.

A mellow voice issued forth: "You have come to report, Surveyor N-G." The words hummed around the hall for three or four echoing revolutions. It did not sound like a rebuke. Lanok rummaged in his mind for the relief which logic suggested he should feel: Dempelath hadn't accused them of interruption; evidently they were expected; might all yet be well?

From a sudden vertical stretch of the podium lights it appeared that the ruler of Olhoav was rising to greet them. At the same time some of his cmem glow-particles detached themselves from the main body, to form outward-curving flakes of scrappy illumination suggestive of a host's arms stretching to greet his guests.

"Yes, Weigher-Glomb," replied Surveyor Nuth Geven, "I have come to report on the recent tremor."

"Report, then. Tell me what you have learned."

"Since you command the truth... It is the harbinger of structural calamity for Olhoav. Within days at most, we're in for a real, foundation-splitter of a crackup."

"And therefore? Your advice is...?"

"Glomb Dempelath, I have come to recommend that you lead a temporary evacuation of the city. Otherwise a large number of people will die."

The airy lights of the cmem danced closer to Nuth Geven and to his awed youthful companion.

Nuth asked me to be a witness, remembered Lanok Ryr. A witness to history in the Menestegon hall; how appropriate; just the place for it. Has there ever been an evacuation of Olhoav before? Never heard of one.

"People will die," echoed the Glomb. "People who are not suited to this epoch; yes, they will die."

"What do you mean?" cried Nuth Geven in a outrage.

The ruler's gentle reply was borne on a mellifluous breeze, as the outlying glow-flakes fluttered close enough to affect the hearers' brains with the sweet reasonableness of Dempelath.

"I only mean the obvious, that those people who will die in the city will have refused to leave it, their refusal due to their fear that they might never get back in afterwards. In a mirror of this argument, I and my followers, likewise, were we to evacuate, might have to fight our way back in when the emergency is over."

"Excuses for doing nothing!"

"No, it is fact. While the struggle for the soul of Olhoav continues, neither side will risk abandoning the city's body."

So luminously reasonable, sliding so persuasively into the brain!

In desolate fury the Surveyor gasped, "It is the plain truth that you care more about your power than about the lives of your people. And this foundational crackup is your fault anyway. Diversion of resources, neglect of the city's fabric - "

"Ahhh," hissed the swirling cmem, "blame it all on the Revolution, eh? Not on what made the Revolution necessary?" Swirl, swirl, unanswerable -

Seeking to draw his laser, the Surveyor found that it seemed stuck in its holster at first; then it came out with so sudden a release that he almost dropped it. He strove to raise it, to aim it at the tyrant who was looming and swelling in the middle of the hall. Yet a disobedient arm and fist began to twist the weapon's muzzle towards the Surveyor's own head. Out of the corner of his mouth he muttered, "Get out of here, Lanok. I'm a dead man and you're my witness. Move!"

Lanok Ryr stood rooted in indecision, finding it nigh impossible to believe that the Surveyor really would be compelled to fire at himself. Surely, the Glomb merely intended a demonstration of power? A scary lesson followed by a show of merciful forbearance? Such would be the statesmanlike course; such would befit a rightful ruler.

It takes a a great deal of pressure to make a Uranian sweat. Nuth Geven's glistening, beaded face was what finally convinced Lanok Ryr that the battle, which the Surveyor's muscles were on the way to losing, was for real. Worst of all were the sly nudges towards acceptance, even approval, of the sick thoughts infiltrating Lanok's mind. It's Nuth Geven's own fault, came the verdict at the very moment when the Surveyor's finger squeezed the laser-stud. He ought to have known better, was the pronouncement as the Surveyor's head-burned body collapsed. It is foolish to defy a ruler whose duty it is to preserve his own authority intact. For the good of the state, the Power in charge cannot afford to let insolence pass.

Immediately after the killing, the light-flakes began to retreat, but a pesky-plausible remnant of the cmem's influence still nested inside Lanok's head and scuttled around establishing up claims for credence. His better self sought to stamp them out, but it was not possible to force lungs and throat to form any protest at the moral inversion whereby the victim, Nuth Geven, was blamed for what had happened. Nor was Lanok able to assert himself even by means of energetic flight. Despite the Surveyor's last entreaty, there was no need to flee; nothing threatened Lanok Ryr. He was just a boy, beneath notice, not worth the slightest fraction of the tyrant's attention. The devastated youngster could only stagger weakly away, to slink off home.

5

Hardly more than blindly aware of his route back - towards Flexion Five along the Choot Skimway in the district of Occoz - he had one remaining desire. The desire for oblivion.

It did not occur to him to report to anyone what he had seen. Nor could he look forward to getting any normal work done today. No such notion could survive the morning's catastrophic start! When he reached his home bafract, he collapsed on his bed.

His murky stupor deepened into a timeless coma, and when finally he emerged from it he did not know the hour, nor even the day.

The face of his mother was gazing down at him.

Sajur Alsom wore a look of harrassed calculation as she said, "Son, do you need to tell me anything?" Not, what have you been doing, or what has happened to you. She well knew that city maintenance, nowadays, could involve themes that were risky to discuss.

Lanok sat up and said, "I need to take a message to the Noad. Urgently."

She asked a question that would never have been asked in the old days:

"You think you can find him?"

He grimaced, "It could take a while."

In the old days, you found the Noad quickly because renl gave him "findability". Sajur, in view of current conditions, refrained from comment. But then she struck a wrong note: "Are you going to the Palace, then?" Ah, she could have kicked herself after uttering those words.

"Oh, certainly," replied Lanok sarcastically while his mother bit her lip. "Out of respect for the way things used to be, I'll look for the Noad in the Palace of the Noad; and then, after I've failed to find him there, I'll look for him in the house of his wife, where he now mostly lives in the manner of a private citizen with no cares. And if he's not there either..."

He paused. Irony was not his usual style; his bubble of caution had burst just then. And if he's not there either... How to finish the sentence? He cut off his flow of words and, instead, shrugged so as to express the reassurance that he would if necessary hop onto the sort of current that gets you somewhere; out loud he said, "I'll swishalong."

Great compensations are enjoyed by the masses of lowly lives who form the carpet under history. If you belong to that great multitude of supporting cast, tacitly known as backgrounders, whose resilient weave supports the tread of the notable few, you can securely browse the nutriment of reality, since you basically and indisputably are the quiet glory which no fame or imagey glitter can beat. Moreover, even as a bit-player you may find yourself stepping (albeit briefly) into the spotlight at the crux of a tale. At such moments you can achieve parity with protagonist foregrounders.

6

On that same Tremor-Day (as people began to call it), Gevuldree, wife of the Noad, skimmed as fast as she dared through the angled ways of the urban jungle.

She would have made even better speed had her vehicle not borne an extra burden: the blanketed body of her husband, deposited on the pulled-out side-deck.

Wrenching the steering lever this way and that, she tore into Jihom District. Her one idea was to reach a friendly house: the home of one who was reputedly still a favourite of the reclusive city-brain. Frantically she had lit upon this plan as the only imaginable hope for Barlayn Lamiroth.

Gevuldree reached her destination, dismounted, palm-pressed the door-bell, and was relieved to hear the sound of footsteps from inside. Hyala Movoum must fortunately be at home...

The door opened to reveal the tall, stately presence of the beautiful healer. Odd thoughts were apt to surface at the craziest moments. "Backgrounders," this same Hyala had said, when filling the ceremonial role of Staunch Woman at Gevuldree's wedding to Barlayn, "don't need

fame to make them great in the records of eternity... It is better to be

obscure and decent, than to be famous for the wrong things." Patronising words, in the opinion of those who supported the Revolution; but the Noad's young wife had taken them at face value, and now she cried for succour to the foregrounder who had spoken them.

Hyala did not disappoint. In one glance she saw that this was no moment for questions. At once she slid the hovering skimmer to her receptor rail, and then helped to dismount the unconscious man. Between them they carried him into the house. Having laid the Noad on a couch, the healer then listened to the distraught wife's story - what there was of it.

"So little to say!" wailed Gevuldree. "He was down in the basement of the Pnurrm. Must have gone down there just after the tremor..."

"To look for structural damage," put in Hyala. "And you thought he might be in danger from further subsidence?"

"I suppose that was why I went down after him, yes. But as it turned out," and Gevuldree looked towards Barlayn's blotched countenance and sightless stare... and did not finish her sentence.

"Had he been threatened recently?" asked Hyala.

"Not that I know of," came the miserable reply. Gevuldree's blonde tresses hung limp around a bowed face gaunt with grief. "Not much notice was being taken of him at all. Sponndar H-M, please can you tell me, what has happened to him?"

Instead of replying, Hyala relayed the question, calling out in a changed tone, "DYNOOM!" (Gevuldree's lips parted slightly: in her thirst for hope, she had been right to come here.)

The disembodied voice of the city brain filled the air around them with a murmured, "You have my attention. I can tell you what has afflicted the Noad. It is the noppt oartuc, the Sixty-Day Disease."

With a wild stare the Noad's wife gasped, "The what?"

Hyala said, "I've heard of it. It means... what it says."

"I regret to confirm," resumed the voice of Dynoom, "that the affliction is accurately named. Though he will recover consciousness in a day or two, he will not live beyond sixty days from now."

Gevuldree took three deep breaths and mastered herself. She did not ask any futile questions about how the calamity could have occurred. The basement of the Pnurrm was crowded with objects brought in from the wilderness; on rare occasion one of them might release a rhoufah, an unwelcomeness. (Uranians simply accept that life is like that.) The point was, how best to respond. Presently, in bitter determination to counteract, so far as was possible, what had been done, she ground out some words: "Shortly, then, Barlayn will wake and be able to decide what to do with the remainder of his life. Sixty days; not much, but not nothing. But will his recovery be too late to allow him any room for what he may wish to do?"

"Go on..." prompted Hyala. "In my house you can speak clearly, freely."

"I mean that whoever did this, and we don't need to name names, will have done it as part of a plan... and the plan, Hyala, will involve your misty-minded guest, the Daon."

"The nebulee who, it now appears, will become Noad in sixty days."

"Exactly. A piece in the game. We should decide now, whether to hide him. We may have no time to lose."

Brows lifted in admiration at the girl's new clarity of thought and speech, Hyala nevertheless demurred: "Even assuming you're right, that the Noad's infection was no accident... concealing his successor may play into the enemy's hands..."

"Not doing so will leave him in the enemy's hands more literally!"

Hyala persisted in doubt. "I still don't know. DYNOOM! Can you advise us?"

The city-brain replied in its detached tone:

"The way ahead for the Daon forks into two main routes. I shall call them Route One and Route Two. Along the first of these, you hide him, you take him away, out of reach of Dempelath's power. That must mean away from Olhoav. He then becomes a leader of peripheral survivors: people who have abandoned the city and who subsist in freedom on the edge of the wilderness and beyond. Route Two, by contrast, is an event-line that keeps him in Olhoav, an on-scene focus of hope, working to subvert the tyrant's schemes from within. If you ask me which of these two options would have been favoured by Barlayn, the only answer I can give is, it is impossible to say."

"But which route in your view is better?" asked Hyala.

"Please don't ask me," said the Brain.

The women listened for another half minute, but the Voice, which had cut off like the snick of a closed switch, stayed silent.

Hyala sighed, "Dynoom is getting more like that these days."

The other girl clenched her fists. "Well," she said desperately, "let's decide, you and I, alone."

"Do you feel any certainty, Gevuldree?"

"Yes! I say we should hide the Daon. I say, don't let the Glomb get both Noad and Daon into his clutches at once. Not while they're both weak and sick. What say you?"

"You're not sure, though, are you?" evaded Hyala. "I wanted a second opinion which isn't mine..."

"But the big Brain has let you down! So you'll have to say it yourself, if you think that we should not hide the Daon; that we should not seek a refuge in the wilderness..."

Hyala nodded. "That is my instinct, yes. You, naturally, understandably, might wish to hold Nyav out of reach as a sort of insurance for the last part of Barlayn's life..."

"I'm more concerned with safeguarding what's left of his life's work! Because I love him, I value his aims." The two standing women glared at each other, on the uncertain edge of a quarrel.

At that moment the door-chime sounded.

"Ah," murmured Gevuldree, "it's too late."

"Don't say that," whispered Hyala.

Gevuldree said no more, but went to sit beside the inert Noad, while Hyala went out into the hallway.

A minute passed, and then another. To the sorrowful and anxious backgrounder, seated beside her doomed husband, the current of great events had become more than ever a nauseous swirl, a pressure which (despite her professed concern for the Noad's aims) she would gladly escape along with life itself, so that she might start anew in another, future existence, perhaps loving someone less loftily ranked, less likely to attract the scythe-blade of destiny -

She looked up. Hyala had come back in with a man who was hardly out of boyhood. The youth's face wore a look of stunned endurance. A fellow-loser, thought Gevuldree; not an enemy after all.

"This is Lanok Ryr," said Hyala in a neutral tone. "I've just told him about the Sixty Days, because he has come to report to the Noad, and loyal people had better be informed. Lanok, you want the Noad; here he is..."

The newcomer stared in utter dismay at the disease-painted skin of the unconscious man on the couch.

Gevuldree murmured to Hyala, "Report on what?"

Hyala murmured back, "Advice from the Surveyor - and news of the Surveyor's death."

Gevuldree sighed irritably. "Important, no doubt, but meanwhile we are delaying making up our minds what to do with the Daon! We've got to sort out..."

"No," whispered Hyala. "You and I, we weren't getting anywhere, but now," and she nodded towards the appalled Lanok Ryr, "we can..."

"Get him to help?" asked Gevuldree, blank-faced.

Nodding, the other woman confirmed, "Give this youngster a casting vote."

Unfamiliar though that Terran term was to Gevuldree, she began to be swept along by the idea that Lanok Ryr could indeed be the one to decide whether they should flee with Nyav and abandon the city, or stand their ground and try to turn Dempelath's game their way.

Terran readers, you who live on a world whose atmosphere is composed of mere gases, it is not your fault if you cannot swallow the procedure here. From where you are, how could you possibly understand why a pivotal decision should be left to a boyish messenger who happened to be on the spot at the crucial moment? But if you could live here on Ooranye, where the air is alive with Fate's electric fingers tracing the lines of destiny's flows, you would have wordlessly sensed those invisible lines reaching round Lanok Ryr and encasing him in a decision-box at which are convergingg all the wires of influence from the other agents in the narrative: lines from Dempelath and the late Nuth Geven, from Hyala and Gevuldree, from the inert Barlayn, and from the dazed, hybrid-minded Daon Nyav who during these moments was convalescing in a separate room, out of sight of those who were discussing what to do with him.

Aside to Hyala, Gevuldree conceded in a whisper, "You tell him what we want. I trust you to put the choice fairly." Her tone was no longer bewildered, no longer incredulous, in this room that stank of impending decision.

Hyala stepped closer to Lanok and gently began, "You were right to come here, even though - " she gestured at the sick Noad - "he can't hear you."

The youngster blurted, "You mean, I must simply wait for him to wake up?"

"I mean that your errand hasn't failed; its trajectory was not wrong... You're here to tell us - now that the Noad is doomed - which option we should take with his successor, the Daon."

Lanok stared back at her, sensing the impingement of his own doom, which was that he, a mere bit-player, must face the spotlight at this juncture.

"The options being...?"

"We either hide Daon Nyav, flee with him, smuggle him out of reach of the tyrant - or alternatively we take no action and we just hope that Nyav with his new Earthmind can mitigate and undermine Dempelath's regime from within."

Stooping for a moment, Lanok frowned, then shook his head and abandoned calculation. Looking up brightly he said, "Let's ask him."

For a moment the sublime simplicity of that notion stunned the two women. They glanced at each other... and began to smile. Ask the Daon himself! Lanok saw their positive reaction, and took heart from it. He began to imbibe the sense that he had given the right nudge to the current of events; that he had propelled its vector's arrowhead towards its target. Ask the Daon... ask the dreamily imbecilic Daon! This could be the day on which such a move might be made!

Hyala swayed, put a hand on Gevuldree's shoulder, and said with swimming eyes, "Did you hear that? Just ask him! A delightful idea - maybe a solution!"

Gevuldree also evinced some sparkle of hope, but she said doubtfully, "Nyav still doesn't speak much... he's still mostly a nebulee..."

"But he's coming out of it, day by day; gradually to be sure, but enough to speak entire sentences on occasion... We'll try it! We can but try."

7

The ego-track of Neville Yeadon:

She's addressing me. Must listen. Sounds serious.

"...And thus, because you are now our acting Noad - our ruler de iure..."

Skies above, these Uranians have even learned from me how to mouth phrases in Latin -

"...and because time is short and the arguments finely balanced..."

Hyala, while saying all this, looks so keyed up, she makes me cough - and my cough halts her words.

The way she and the other two, all three of them in a solemn row in front of my armchaired self, are standing like pupils in a viva examination, cause me to open my mouth likewise, before I know what to say. They're staring at me with anxious hope. They've heard me speak each day grdually a little more, and now they seem determined to hang on to my every syllable.

I manage to finish her sentence for her:

"...You wish me to tip the scales."

Those last three words I utter in English.

They open their eyes wide in comprehension, so much do they now know of my language. As for me, I reckon I know what they want. I spend no more than a second on reviewing the two options, understanding from Hyala's summary that they need a quick choice from "Go or Stay". The answer comes to me fast although I have nothing but gut instinct by which to determine the issue.

The attractively adventurous, open-ended prospect of leading a group of exiles in the penumbra of the settled land around Olhoav, and exploring the grass forests beyond, appeals to me. Yet as regards adventure, won't it be great either way? On this stupendous planet I must be in for excitement wherever I am... and I dislike the idea of fleeing, especially if I'm retreating from an enemy whom I have never seen and whom I do not properly understand. From that point of view I'd rather stay.

Besides, this city of Olhoav now counts as my home.

"My answer is," I said, "I'll stay."

The utterance of these words exhausts me. A wave of weakness overcomes me and I slump back in the armchair; so far am I from being well, that the images of my three questioners undulate before my eyes. Yet I do catch from their faces a certain thankfulness.

All along, apparently, they wanted me to stay.

8

After another tremor during the night, I look out of the front window and see some evidence of damage in the street. Mostly, a litter of shreds of material shaken down from the higher terraces and levels; broken stuff, scattered across the floor of Otett Avenue. Also some fallen metal struts - which I hope don't mean that a walkway or skimway is about to collapse onto our roofs or heads.

I totter back to bed...

Another couple of days pass.

Hyala and Gevuldree have taken to putting me on show. Don't know what else to call it. They invite group after group of visitors. The citizens gawp at me and exchange grins of delight whenever I manage a few phrases.

Their questions aren't too hard. How do I like it here, how am I feeling compared to fifty days ago, is it uncomfortable to have Terran memories occupying a corner of my brain... These good folk must have been told (or perhaps they instinctively know) to steer clear of delicate political subjects. Truth to tell, I get the feeling that it doesn't so much matter what I say; they simply love to hear my voice. It confirms to them the miracle, that this nebulee can actually speak... I hope my two women minders know what they are doing. From what I understand, it's decidedly unsafe to compete in popularity with the real ruler of this place. On the other hand, in my case maybe it's also unsafe to lack a following. It could be a kind of insurance, to spread the knowledge widely, that I'm substantially conscious... raising my rarity value as a symbol... provided that I'm still too weak in body and mind to offer a real threat to Dempelath. This is treading a fine line.

So delicate is the balance, in fact, that I can well guess why the Noad - who's awake now - isn't coming to see me. It would be too risky to be seen concerting strategy with him... though I do wish I could get his advice while he's still alive to give it. When his sixty days are up it'll be too late.

I meanwhile try to comport myself with kindness during the public's question-time. It costs me an effort, sometimes, to keep my sardonic thoughts to myself.

An over-smart young woman says, "Daon N-Y, are you comfortable when you look to your future role?"

"Shush, Bizzid!" grate some of the others.

I raise a negligent hand. My gesture is meant to indicate that no fuss need be made, that the question, though regrettable, is one which I am prepared to answer. "Comfortable," I confirm, "yes I am comfortable. Insofar as one can be, who is living on borrowed time."

It is the first time they have heard that phrase - translated from English - and it does something to them as they ponder its meaning. I observe that their linguistic excitement is vying with a certain glumness. To steer towards the fun side of things I add, "It's a matter of waiting for the chickens to come home to roost..."

"Chickens?" asks one member of the audience.

"A type of little bird," I explain.

"But why?"

"Come to think of it, I really don't know."

My thoughtful bafflement gets a laugh.

All this while, drained further of strength by the strain of these hours of being put on show, I become ever more frustrated by my flaccid body and woozy head... To think of all those books of heroic interplanetary adventure I used to read! Shame that I can't put on a better performance.

Fact is, though, that at this stage it's up to Hyala. She's doing her best to ensure that when the confrontation comes, the enemy won't be able to conceal me utterly or pretend I don't count. And although I'm on edge, I know it's my simple duty to keep my nerve while I wait for that enemy to make his move.

Perhaps he, too, is waiting.

9

This must be it - the big crack-up. I am roused from a doze by being thrown across the floor.

Luckily none of the furniture lands on me; I'm merely bruised.

I stagger up amid the strewn stuff. I look around the rooms. Hyala is nowhere to be seen; she must have gone out. I pray she was in the clear when the quake hit, if there is any "clear" in this three-dee urban maze.

The house itself must have been constructed of immensely strong, detachable units; the quake has separated some of these components, allowing me to see out through regular fissures. In my half-stunned mind, waves of cowardice and recklessness clash. I lurch in childish reaction back towards my room, with a stupid impulse to get back to sleep. Then, reproaching myself, overhauling my attitude, I veer to go out. Perhaps there's something helpful that I can do.

Leaning on a stick, I cross the now tilted threshold. I emerge into an altered scene. Above me there's a slump in the skimways, where some of their support-towers have sagged towards each other. Contrastingly, in the adjacent section, similar elements have come apart.

Glancing back at the house to reassure myself that nothing has fallen on top of it, I perceive that it has been dragged askew by one of its upper connections. I see more and more damage and distortion as I look around. Most appalling is the fissure that now gapes about a hundred and fifty yards to my left, across the avenue. Fissure? Chasm, more like. Maybe fifty yards wide. Perhaps two dozen people are running about in the middle distance. A few others are picking themselves up off the city floor. They don't look so bad - I probably need more help than they do - but I don't care to think about any folk who may have been in the region of that big crack...

A loud blare makes me jump. "CITIZENS", cries a loudspeaker - and we all look around wildly and unsuccessfully to spot the source of that voice, that dreaded, well-known, bone-penetrating voice. "REMAIN IN OR AT YOUR HOMES. THE GOHIK UGRAON [Reconstruction Corps] WILL DISTRIBUTE AID AND ASSIGN YOU YOUR TASKS, AND MEANWHILE YOU MUST REMAIN IN OR IN FRONT OF YOUR HOMES - "

Everyone seems to shiver and jump into motion in order to obey the unmistakable voice of Dempelath.

After fifteen or so repetitions of the command, the scene has emptied of people. I likewise turn and go back inside.

I mount the stairs to an upper window in order to keep watch. Dempelath has not missed a trick; the speech must have been long-prepared.

After half an hour I spot a mass of folk rounding the corner of a side-street, in front of my view of the chasm. In unison they turn about and proceed along the avenue in my direction. They are in chevron formation: a waon like the one I first saw in the park, and like others I've occasionally seen. This time, though, they make no howling noise. No noise at all, except the ever-louder tramp of boots as they approach the house. I reckon they're coming for me.

I see a peculiarity about them which did not exist before: white squares, held fluttering their right hands. Whatever it may mean, I don't at all like the look of that crinkly whiteness. I would prefer the fellows to be brandishing lasers. Why? I cannot formulate a reason for my hunch. Will they go on past? Most of them do, but about sixteen of them split off from the rest. This detachment heads for my front door. Definitely they are coming for me. Among them I recognize Lanok Ryr: a changed Lanok Ryr.

Oh, well. I compose myself in my chair. Nothing for it but to wait for them to barge in.

It's smoothly done. Four of them, including Lanok, line up facing me, holding their white sheets of... paper. It's paper. Never seen so much paper on this world before.

Lanok, very formal, as though he has aged hundreds of days since I saw him last, says, "We are of the Gohik Ugraon. We have come to move you to a safe place, Daon N-Y."

"That sounds ominous," I smile.

"You will be well protected." Lanok is now a hollow-cheeked, humourless automaton. I nevertheless sense in him a remnant of unease at what he is about to do, and I surmise that whatever has been done to him has suppressed but not erased his personality.

I parry with, "Should a Daon be well protected? Should he not rather share the risks of his people?"

He shrugs with a phrase that brings me a truly unwelcome reminder of Earth:

"I did not make the rules, Daon N-Y."

They take a step closer.

Rising from my chair, I heave a sigh and say, "Show me your warrants, then, and I'll come quietly." I'm at any rate thankful for Hyala's absence. She, thank the skies, hasn't been caught up in this trawl.

"Warrants?" says Lanok in a puzzled tone.

"That," and I point to the paper he's holding. But it's no good, I can't pretend; the sheet is empty on both sides, a fact which the lad reveals as he turns it around with a bewilderment equal to mine, and the other three men do the same. I experience a prickling of almost superstitious fear and revulsion which I can't even remotely define or explain. The blankness of these sheets of paper is almost as scary as a row of human faces without features.

It's just as well that I'm not dragging any of my friends with me into this pull, this vortex...

But when I'm brought out through the front doorway, with my escort around me, and the other twelve guards waiting on either side, I am further dismayed to see on the pathway the hurried figure of Dittri, my little carer, the fluffy girl who comes every two or three days to look after me. Culpable fool that I am, not to have put an end to that arrangement! Dittri trots into the trap: the rest of the men close around her.

"Oh, dear," she says, in English, as she and I are marched together onto the avenue. I form words to apologise but, beating me to it, she commiserates with me: "You were getting better, Daon Nyav, and now this has to happen..."

What can I do but put an arm around her and shake my head and give a helpless laugh? Then, to Lanok: "Is the girl arrested too? If so, why?"

"I didn't make the rules," the youth repeats.

Dreading to see us headed for some downward ramp, or other means of descent into the vaults, I concentrate my attention on the city floor. We approach the chasm that has wrenched the northern from the southern length of Otett Avenue. To my relief, before we reach that gulf we do a left turn and veer into a side street. I think we're now headed towards the centre of Jihom District.

10

Some of the people we pass recognize me. I fleetingly wonder about the chances of appealing for help, but, as usual, I can't properly size up the situation. Blank or indecisive glances, perfunctory hails, suggestive that they believe I'm being escorted by some guard of honour... doubtless they know I'm not a completely free agent, but, nowadays, who is? And why should I expect them to do something for me, given that I can't do aught for them? If they could expect help from me, they might make a move to rescue me, perhaps. As it is, I dare say they're used to the idea of me being shifted about. I'm a sort of mobile symbolic standard, fairly important as part of their heritage, but today they have more urgent matters on their minds.

The only thing that might rouse them to try to effect a rescue, would be if they knew that I was being threatened. And since I myself don't know that for sure, why should they? Round and round churn my thoughts.

We make a right turn, and march onto a pentagonal plaza. Here rises an imposing stone pile, with casemented walls wrapped in exterior spiral ramps, surmounted by a huge oval dome which, in turn, is topped by a hemispherical summit. My heart sinks as I admire the edifice. All along, I have feared that my destination would turn out to be the Menestegon - effectively, nowadays, Dempelath's Palace.

It looks undamaged, its "hair" of upper connections a trifle mussed, no more, by the quake which has sheared through some of the cables and access tubes that ought to link the great dome to the higher, slenderer terraces of Olhoav. I shrug, momentarily out of love with Uranian latticed architecture; moodily I reflect that a Terran designer might judge the after-quake scene to be no more untidy than what had appeared before. A yearning for Earth pierces my heart. What in the name of all the skies am I doing here, on a mystery-stuffed planet like this, where an infinity of accidents can be made to happen to one who stands in a tyrant's path...?

One weakness I share with my childhood hero John Carter is a dread of lightless dungeons. I hope to goodness I'm not headed for any oblivion of that sort.

As we approach the portico I make one more desperate attempt to communicate with my arrester, Lanok Ryr.

"I'm being put away? Down in the vaults somewhere? Beneath the Weigher's Palace?"

Lanok turns his head. "Not down," he says cryptically. "My orders, Daon N-Y, are to take you up."

We enter the Menestegon. We tramp through its lobby; next, our strides echo around the edge of the dim and empty main hall. At length we reach an elevator cage at the back.

Dittri and I are ushered in, and with us enter four of my escort including Lanok, whom I don't question further lest I be reminded again that he "did not make the rules". The cage begins to ascend. My spirits rise too, alleviated by the demise of the fear of being buried out of hand. To be going up, rather than down, is so comparatively reassuring that I now feel quite recovered from my panicky wish to be back on Earth. Granted, here the cards may be stacked against me, but the game still fascinates; even if I could, I wouldn't abandon this world.

CONTINUED IN

Uranian Throne Episode 13: