forays into the furnace:

alan e nourse's

brightside crossing

and

other writers' Mercurian days

[ + link to podcast ]

Extreme conditions are a challenge not only to those who brave them in real life, but also to those who would describe them in fiction. Brightside Crossing meets that challenge triumphantly - and gives us one of the classic tales of the Old Solar System.

How did Nourse do it? Here's a clue from C S Lewis' A Preface to Paradise Lost.

...Towards the end of Book III Milton takes Satan to visit the sun. To keep on harping on heat and brightness would be no use; it would end only in that bog of superlatives which is the destination of many bad poets. But Milton makes the next hundred lines as Solar as they could possibly be... Heaven and Earth are ransacked for simile and allusion... to guide our imaginations with unobtrusive pressure into the channels where the poet wishes them to flow...

In other words, to succeed in this game you have to be indirect. You have to manipulate the reader subtly, rather than bludgeon him with adjectives and gosh-wow.

a planetary hell

Nourse displays the power to thus "guide our imaginations", but because the short story we are considering is so short (only 23 pages), he needs to combine indirect manipulation with the direct punch.

His technique is to make them work in tandem.

..."Brightside of Mercury," the Major said.

I whistled cautiously. "At aphelion?"

He threw his head back. "Why try a Crossing at aphelion? What have you done then? Four thousand miles of butchering heat, just to have some joker come along, use your data and drum you out of the glory by crossing at perihelion forty-four days later? No, thanks. I want the Brightside without any nonsense about it..."

But this is not straight narration; this is a flashback; indeed, most of the tale is flashback; that's its main indirectness.

The straight narration - by Peter Claney, sole survivor of the expedition - is simply his effort to convince his would-be successor, James Baron, that any further attempt to cross the Brightside of Mercury would be equivalent to suicide.

Peter Claney shook his head. "I can't tell you anything you want to hear."

"But you've got to. You're the only man on Earth who's attempted a Brightside Crossing and lived through it! And the story you cleared for the news - it was nothing. We need details. Where did your equipment fall down? Where did you miscalculate? What were the trouble spots?" Baron jabbed a finger at Claney's face. "That, for instance - epithelioma? Why? What was wrong with your glass? Your filters? We've got to know those things. If you can tell us, we can make it across where your attempt failed - "

"You want to know why we failed?" asked Claney.

"Of course we want to know. We have to know."

"It's simple. We failed because it can't be done. We couldn't do it and neither can you. No human beings will ever cross the Brightside alive..."

Indirectness, talking about the dangers, tensing the reader by dire implications, comes with discussion of the equipment for the Crossing. Baron asks:

..."What kind of suits did you have?

"The best insulating suits ever made," said Claney. "Each one had an inner lining of a fiberglass modification, to avoid the clumsiness of asbestos, and carried the refrigerating unit and oxygen storage which we recharged from the sledges every eight hours. Outer layer carried a monomolecular chrome reflecting surface that made us glitter like Christmas trees. And we had a half-inch dead-air space under positive pressure between the two layers. Warning thermocouples, of course - at 770 degrees, it wouldn't take much time to fry us to cinders if the suits failed somewhere."

"How about the Bugs?"

"They were insulated, too, but we weren't counting on them too much for protection."

"You weren't?" Baron exclaimed. "Why not?"

"We'd be in and out of them too much. They gave us mobility and storage, but we knew we'd have to do a lot of forward work on foot." Claney smiled bitterly. "Which meant that we had an inch of fiberglass and a half-inch of dead air between us and a surface temperature where lead flowed like water and zinc was almost at melting point and the pools of sulfur in the shadows were boiling like oatmeal over a campfire."

The build-up takes 9 pages. Then we have 13 pages in which Claney narrates the actual attempt at the Crossing. Then we have one final page in which the two explorers argue some more, in the light of the story Claney has now told.

This includes a few lines right at the end, which form the perfect, ironical ending to the tale. I won't give away the punch line, but it really does provide a perfect comment on that aspect of human nature which drives us to attempt the impossible...

Harlei: So what about the direct stuff, Zendexor? The central part of the story, Claney's experiences during the Crossing -

Stid: Yes, it's time we looked at how the author faces up to it directly. As you started by saying, Zendexor, that's the challenge. You've said enough to convince readers that the build-up is good. But many a tale has been good on promise and poor on delivery -

Zendexor: Let me tell you, it's good. The narration weaves and flows like some brilliant orange river of lava, bearing along with it the terrifying landscape, the men's feelings, their psychology, the practicalities of the expedition, its discoveries...

...I kept my eyes pasted to the big Polaroid binocs, picking out the track the early research teams had made out into the edge of Brightside. But in a couple of hours we rumbled past Sanderson's little outpost observatory and the tracks stopped. We were in virgin territory and already the Sun was beginning to bite.

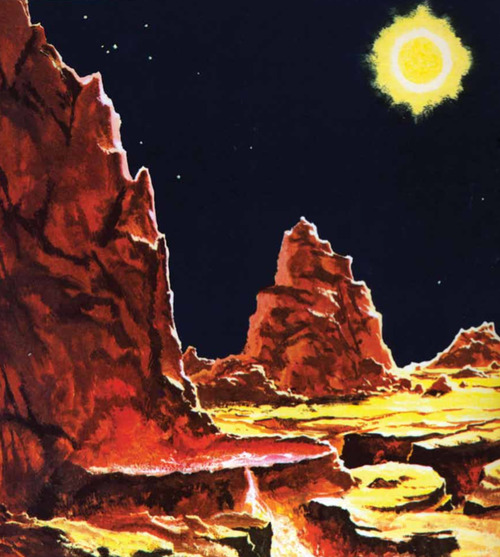

We didn't feel the heat so much those first days out. We saw it. The refrig units kept our skins at a nice comfortable seventy-five degrees Fahrenheit inside our suits, but our eyes watched that glaring Sun and the baked yellow rocks going past, and some nerve pathways got twisted up, somehow. We poured sweat as if we were in a superheated furnace...

What do I most remember about those next few pages? The discovery of the remains of a previous expedition... Claney's vehicle almost being sucked down into a pool of molten lead... and what for me was the greatest terror, a brittle zinc shelf overhanging an abyss... and the overarching theme of the horrendous, stark, baked landscape and the challenge that could not be met.

And then there's the human element, which the author handles memorably.

Peter Claney's attempted Crossing was a four-man expedition, led by "The Major" Mikuta, a strong, stable character, and including, besides Claney, a flamboyant character named McIvers, and lastly a youngster called Stone. The tension between McIvers and the rest gives an extra dimension of drama to the tale, and a thought-provoking aspect too - for Baron and Claney disagree afterwards as to the verdict. When disaster struck, was McIvers to blame? Baron thinks it obvious that this was so. Claney denies it.

..."We had to keep to our schedule even it it killed us, because it would positively kill us if we didn't."

"But a man like that - "

"A man like McIvers was necessary. Can't you see that? It was the Sun that beat us, that surface..." Claney leaned across the table, his eyes pleading. "We didn't realize that, but it was true. There are places that men can't go, conditions men can't tolerate. The others had to die to learn that. I was lucky, I came back. But I'm trying to tell you what I found out - that nobody will ever make a Brightside Crossing."

a wan successor

No close rival exists to Brightside Crossing. But there is another realistic Hot-Hemisphere tale which appeared seven and a half years later, in the same magazine, and which is worth reading at least once or twice.

On this page we're proceeding by gradual steps from utterly inorganic to life-bearing Mercury. We began with a tale that depicts a Mercury where life is not only absent but inconceivable. Now we shall turn to a slightly different version of the innermost planet, one in which people at least thought it worth checking to see if it might harbour life -

Galaxy, August 1963, cover for "Hot Planet"

Galaxy, August 1963, cover for "Hot Planet""...Tom, any use asking you?"

The biologist grimaced. "I've been shown two hundred and sixteen different samples of rock and dust. I have examined in detail twelve crystal growths which looked vaguely like vegetation. Nothing was alive or contained living things by any standards I could conscientiously set."

The story is Hot Planet, and since the author is Hal Clement, we can expect a hard-science story; and that is what we get. The style is as dry as the planet, though both liven up somewhat when a volcano erupts.

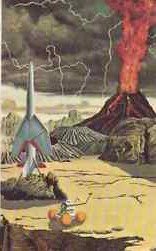

Across the riven plain, whose cracks were now nearly hidden under the new ash, the black cone towered above the nearer elevations. It was visibly taller than it had been only a few hours before. The fountain from its top was thicker, now jetting straight up as though wind no longer meant a thing to the fiercely driven column of gas and dust... patches of red and yellow incandescence showed briefly in the pillar, and glowing sparks rather than black cinders rained back on the steep slopes. Far above, a ring of smoke rolled and spread about the column, forming an ever-broadening layer of opaque cloud above a landscape which had never before been shaded from the sun. Streamers of lightning leaped between cloud and pillar, pillar and mountain, even cloud and ground. Any thunder there might have been was drowned in the howl of the escaping gas, a roar which seemed to combine every possible note from the shrillest possible whistle to a bass felt by the chest rather than heard by the ears...

Stid: Note the reference to "wind". I suppose eruptions could create an atmosphere on Mercury...

Zendexor: Yes, both Nourse and Clement have that as a theme. Quite interesting, this hard-science speculation, these might-have-beens of a synchronous Mercury. But as I say, Hot Planet is an extremely dry story. The plot does allow for real danger, but nothing like what we get in Brightside Crossing, and the explorers are not traumatized in the Clement tale as they are in Nourse's. Neither is the reader.

Stid: So you were traumatized, you poor thing, by the stronger tale?

Zendexor: That's putting it a bit strongly, I admit, but let's just say that Alan Nourse's epic is bound to score deep grooves in the imagination of any youngster - impressions which will last a lifetime. It will also have influenced subsequent writing.

All this is likewise true of our next example, which appeared many years before, in 1932.

Enter Mercurian life -

a captive bound to a salamander

...The glaring light and scorching heat could mean only one thing - that he had been carried into the sunward lands of Mercury. That incandescent thing toward which he dared not look was the sun itself, looming in a vast arc above the horizon.

He tried to sit up, but succeeded merely in raising his head a little. He saw that there were leathery thongs about his chest, arms and legs, binding him tightly to some mobile surface that seemed to heave and pant beneath him. Slewing his head to one side, he found that this surface was horny, rounding and reticulated. It was like something he had seen.

Then, with a start of horror, he recognized it. He was bound, Mazeppa-like, to the back of one of those salamandrine monsters to which the earth-scientists had given the name of 'heat-lizards'. These creatures were large crocodiles, but possessed longer legs than any terrestrial saurian. Their thick hides were apparently, to an amazing extent, non-conductors of heat, and served to insulate them against temperatures that would have parboiled any other known form of life.

The exact range of their habitat had not yet been learned; but they had been seen from the rocket-ship, during a brief sunward dash, in deserts where water was perpetually at the boiling point; where rills and rivers, flowing from the twilight zone, wasted themselves in heavy vapors from terrible cauldrons of naked rock...

Clark Ashton Smith, "The Immortals of Mercury"

Stid: I see the progression. We now have water on Mercury. Boiling water instead of boiling lead.

Harlei: You might still get the boiling lead, too, further into the dayside.

Zendexor: Aside from these observations, let's also note Smith's superb vocabulary and turns of phrase. "That incandescent thing..." "Slewing his head..." "...horny, rounding and reticulated." "...bound, Mazeppa-like..." "...salamandrine..." "...parboiled..." "...cauldrons of naked rock..."

Stid: And who was Mazeppa?

Zendexor: I don't know - refers to something by Byron, I think. But here's another point: for some reason, such literary allusions seem to work by a kind of sonorous effect, whether one understands the reference or not.

Here's another literary point to ponder. Harking back to my quote from C S Lewis at the top of this page - to his disparagement of "the bog of superlatives" - well...

Stid: You're not sure what to say now, are you? I see the problem! For consider the direct hammering the reader gets by Clark Ashton Smith as his luckless hero gets borne deeper into the hell of Sunside:

...The heat-lizard, with an indescribable darting and running motion, went swiftly onward into the dreadful hell of writhing steam and heated rock. The great ball of insupportable whiteness seemed to rise higher momently and to pour its beams upon Howard like the flood of an open furnace. The horny mail of the monster was like a hot gridiron beneath him, scorching through his clothes; and his wrists and neck and ankles were seared by the tough leather cords as he struggled madly and uselessly against them.

Turning his head from side to side, he saw dimly the horned rocks that leaned toward him from curtains of hellish mist. His head swam deliriously, and the very blood appeared to simmer in his veins. He lapsed at intervals into deadly faintness: a black shroud seemed to fall upon him, but his vague senses were still oppressed by the crushing, searing radiation. He seemed to descend into bottomless gulfs, pursued by unpitying cataracts of fire and seas of molten heat...

Zendexor: So how can this escape the charge of being a "bog of superlatives"? I'm on the spot, now. Must defend Smith - for his stuff works; there's no doubt at all that it's brilliantly effective.

Here's my view of how he avoids the boringly monotonous "bog of superlatives".

If you're narrating an extreme condition which demands superlatives, you make sure you "un-bog" them by roughening up the flow of them. You keep them - you have to - but you shake off any monotony by means of variation in technique.

So for instance here we have Smith's cleverly compressed pairings of adverbs ("struggled madly and uselessly"); his unexpectedness ("with an indescribable darting and running motion" - not like the inexorable plodding one would expect of a giant saurian); his use of the pathetic fallacy (the horned rocks "leaned"; the cataracts are "unpitying"); his adjectival sophistication (the "great ball of insupportable whiteness"); his effective similes, not too many of them ("like the flood of an open furnace"; "like a hot gridiron")... Readers can no doubt add to the list. Try it. Work on the following:

...he saw his surroundings in broken glimpses, through turning wheels of fire and bots of torrid color, like scenes from a mad kaleidoscope.

The heat-lizard was following a tortuous stream that ran in hissing rapids, among twisted crags and chasm-riven scarps. Rising in sheets and columns, the steam of angry water was blown at intervals toward the earth-man, scalding his bare face and hands. The thongs cut into his flesh intolerably, when the monster leapt across mighty fissures that had been made by the cracking of the super-heated stone.

Howard's brain seemed to broil in his head...

a more evolved threat

This site already has a vast number of references to that unique novel of the Twilight Belt, Valeddom. Let me briefly add just one more.

Imagine you are in a vehicle having explored a little way into the Bay of Cholvg in the Dayside inferno, and you want to get back. You get to the cliff-tunnel which will lead you back to base - to the city of Vutu on the edge of the Twilight Belt.

And something is in between you and it.

...I gaped at the image of dinosaur-length strokes of green fire splayed on the ledge. Salamanders, whispered the memory of legend. Sketchily beautiful like the prehistoric Uffington White Horse on the English chalk downs, so that I could see the cliff face through their transparent interiors, their reptilian outlines seemed to fumble jerkily as they climbed and jumped over one another...

So we come full circle, from the terror of going out to the terror of not being let back in...

Alan E Nourse, "Brightside Crossing" (Galaxy, January 1956); Hal Clement, "Hot Planet" (Galaxy, August 1963); Clark Ashton Smith, "The Immortals of Mercury" (booklet, 1932); Robert Gibson, Valeddom (2013)

See the page NOSS - How Far Can We Go? where the foolhardy explorers' mind-set in Brightside Crossing comes into the debate quite often.

For musings inspired by Hot Planet see the OSS Diary, 23rd September 2016.

For my naive childhoom captivation by the pretty colours of a deadly planetary furnace see Misleading beauty.

Extract: Perilous trek on the dayside of Mercury.