kroth: the rise

3: the new star

“Shoggoth!”

My single-word outburst, caught by a microphone neatly thrust by Mrs Foy G., was heard not only by the crowd behind us but also (I felt sure) on radio and local television. Therefore most of the population of the province of Arroung now knew, or shortly would know, that the Earthmind Duncan Wemyss had put the right name to the Slimes.

I heard around me a whistle of breath and an “Ahhhh…”

Murmurs: shoggoth, real, shoggoth, true.

It was the sound of satisfaction, the satisfaction of being right; but what a thin excuse for standing here while the Successfully Named Thing approaches; and the madwoman beside me (I observed) can actually fold her arms and chuckle….

My shoulders wanted to roll up, hedgehog-fashion, but cringing was no use, the lunacy of it all could not be warded off that way: out there, in plain sight, a real shoggoth – oozed right out of the pages of H P Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness – convincingly rolled in our direction, now less than a furlong distant, while all that my stupid captors could do was to feel good that they had got me to say the word. I tiredly whispered, “Oh my, this is beyond stupid.” But no one heard that – the mike was held away from me now; they’d obtained from me the key word, the name of the slime-thing, and my subsequent words might as well not have been spoken.

Gunnuth squeezed my arm, “Here we hev it, the quite perfict outcome. We knew you were a will-rid man, Duncan Wemyss. Will-rid in all the right books.”

“Can we go now, please?” I said with little hope.

She and the others, as I expected, made no move. She prattled on, for the benefit of the networks: “We knew, of course, that the idintification could be made. But none of us had clear enough mimories of the Dream of Earth, which by now has faded almost to vanishing point. And yit the idintification disperately needed to be made.”

“Mrs Gunnuth,” I pleaded, “we have to get back inside.”

She hummed, “The minimum, the minimum, thet’s what we hed to hev…. just to sicure some solid reason to hope that the Shlugakka are, in the long term, on their way out; that in the largest sinse they are, as you might say, doomed to the dustbin of cosmic history. We ebsolutely hed to hev thet minimum consolation nicessary for us to endure our lives here.”

“Look – that one, it’s not on its way out, it’s coming towards us. Look at it, can’t you see?”

“Birannithep,” she recited, “kennot do without the innergy we steal from the Slimes’ Grid, and so we of Arroung must live nixt to the Slimes. And what thin?” she demanded with a rhetorical flourish. “Close as we hev to be to these amoeboids, which are as hateful to us as they must be to inny human or human-related life-form, what ken we do? How ken we live? Answer – we ken (with your hilp, Duncan) know that they are in a cul-de-sec of re-ellity; know that they will be mere fiction in the nixt stage up. Oh how wonderful it is to know, to hear a men from Earth ricognize the things from a story-book….”

“Oh for krunk’s sake,” I gasped, “will you shut up? Is this a time to make speeches? Put that microphone down! Or better still let me – ” I made a grab for it. She just smiled at me, she was easily too quick for me, and deftly passed it to someone else. I wailed, “They’re not fiction here!” and in desperation, taking them all by surprise, I convulsed, wrested my arms free, twisted to face Gunnuth, seized and shook her, but she again just smiled, dreamily, so I cried out to the whole bunch of them as they resumed their grip, “Make a move, you mad foooools…”

Or – perhaps I was dreaming? But that idea could trespass only while my eyes were averted from the advancing Shoggoth; one glance back in that direction and I must wake to the truth: my number was up. I focussed on one of the thing’s mouths and saw, in horrendous detail, the dark gap’s wobbly slide. Simultaneously beside that mouth an eye sprouted, bulged, liquesced back within seconds into the slimy surface from which newer eyes already protruded…. It is remarkable that I could bear the blast of this sight for as many moments as I did. Perhaps the Shoggoth’s reduced status back on Earth (mere fiction, there) drew some gauzy curtain of disrespect across my vision. Or perhaps it was just my defensive dopiness that masked the stench of reality. But if any such factor helped me on an emotional level, it did not alter my practical convictions. I watched as a cornered mouse might watch a cat that quivers in pounce-poise; not that the dignity of a cat can be fairly compared with the Shoggoth’s nauseating slither, but in either case the not yet allows for fully furnished moments: packed moments, displaying what is to come.

One consolation: at least my stupid captors had become quieter. My cries of protest, evidently, had had this much effect: they had stopped the flow of Foy Gunnuth’s verbiage.

So could I, perhaps, shriek out some more? Might it be worth the effort, the off-chance? The spell – I did not understand it but I could try to fight it – the extraordinary spell which held these dopes rooted in the worst spot imaginable. I pleaded, coaxed: “Don’t keep me here, people! And why keep yourselves here? You’re not your own masters, are you? All right, all right,” and I put in a trace of sophistication, “our motivations are never wholly our own, granted, but come on, don’t you think this is a bit much, eh, just standing and waiting while it comes for us?”

Among those who hemmed me in, one man seemed to have a less drugged expression than the rest, and he mumbled words which sounded like, “That’s Life. We often….” and I didn’t catch the rest of it because he turned his head, perhaps to look askance at the monster, which now topped a second, lower, closer ridge, the last undulation of ground between it and us. I recognized the man. He was the older companion of Nolan who had sat with him on the train. I focussed my attention upon this official, in case he might prove to be less weak-minded than the others, perhaps even as much as half awake. My imagination, feverishly blazing, forged ideas in me which went beyond my own proper grasp, as I managed a desperate stab:

“Whaddya think, folks, has it occurred to you that this may be the end of the line for more than just us here? Perhaps your prestige game has more in it than you realize! Perhaps the Slimes know that they are fiction on Earth! Perhaps therefore they are out to re-constitute a more pliable Earth?! Whaddya think, eh? What would they need for that? Ingredients, maybe, ingredients which will make them real on Earth too? My blood, as it were, mixed with the mortar? Else why bother with me, eh? Look at it! Look what it’s doing! It wants me, I’m too well-read, it wants what’s in me, and you had better see to it that it does not get me…”

The Shoggoth was less than a hundred yards away. Out of its roiling mass, one pseudopod had extended ten feet or so to its left, swinging an item of luggage round to full view on that side: a container, an artificial cuboid which it must have dragged behind it all this distance. The object was blue-grey and intermediate in size between wardrobe and coffin. To see something rectangular “handled” by squelchiness added special disquiet to the nightmare, reminding me that the Slimes at the South Pole were reputed to use housing of a kind, though no one had seen the Lobes of Chunnurulch and lived to tell the tale; was I indeed fated to be the first? The look of that box might have confirmed some of the wildly inventive stuff I had spouted, for it could well fill the role of specimen-collector’s container, but those who heard my cry did not respond; they were satisfied with their own beliefs, and as for me, why should I believe in the rants that came from my own mouth? I was beyond credibility by this time – I who had adapted too far. After all, I had allowed myself to get so firmly clamped into the Naos-frame of mind, that now I viewed the sky underneath me as “up” simply because it was the sky, so that things that were dislodged did not drop down but “fell up” into its blue void – Ah, if only I could take off these magnetic boots and fall away! That would be a clean way to go. But the people of Arroung held onto me, and that served me right, for I had got myself into this. Convinced that I did not deserve to escape my doom, I nevertheless bewailed it with a repeated if only. If only the others could feel the horror I feel. If only they could wake up to it in time. If only they could focus their collective will, to use the few minutes that still remained, to break their hypnotic chains and mine.

These thoughts were heated, but still rational. I could complain in this way while the Shoggoth was part of my peripheral vision, but when I turned to look at it directly – impelled to do so because of fears that I might have underestimated its distance – the sight of it so smote me, that reason shut down. Closer, closer the amoeboid giant dragged itself and its box, and I was paralysed. All thought shut down as my entire self, physical and mental, was clenched in life’s utmost final cringe. Survival – in the presence of death in its most frightful form – was no longer to be imagined. Rescue was inconceivable. Nothing stood between me and –

*

The type of sound I heard next, surely could not be relevant. It was a rumbling of chaotic joy – it was the sound of cheering.

I was in a stupid suspense between thoughts. The cheering cracked my rigid convictions but did not replace them with a comprehensible alternative.

The cheering grew. It had broken the monopoly of horror! But could space exist for good news any more? And the belated timing – most suspicious! Belief and disbelief; suspended between these, what could exist but a monster of suspicion? I could accept the joy of the cheering if it was joy. If whatever was behind it did some solid good to my situation, I might believe. But more likely it was some tricky-soft spatter of drool from the closing jaws of fate, and to be taken in by it would be the worst torture of all. Could anything stop a Shoggoth? Lovecraft himself had said if they were roused they would end the world. Not even the authority of their mighty creators had sufficed to control them. Designed (in his story version) by an alien race as beasts of burden, the amoeboids were not mere lumps of flaccid jelly, they were sinewy masses of a plasm immensely vital and strong, who had evolved a will of their own: the ultimate, intelligent nightmares. Oh but – said the sly little hope – you might as well look. Accept facts even if they tell you that the prospect has altered in your favour –

Breathing raggedly, I stared and saw that the Shoggoth had ceased to advance, and this so weakened my caution and my terror with an infection of relief, that I turned with an involuntary smile to my wildly cheering human companions.

The official I had noticed before, who had been with Nolan, said something to me with a grin. I asked him to repeat it.

He pushed closer to me and said, “Chandler’s done it! He’s – ”

I didn’t catch the rest just then, but I had no doubt that I would hear the whole story before long. I did think that I might have guessed Vic would be behind whatever it was. It was a while since he had last performed a shattering deed, and it would not do to get out of practice. My consciousness then wobbled away for a time; away from coherence. I remember my last look at the mighty Shoggoth. It had subsided into a relatively quiescent hemisphere of grey plasm, about five yards high. It roiled with occasional snorts of disturbance – just a horrible hump of slime, which I could safely turn my back on, so I did, as I dazedly allowed myself to be led back indoors.

*

I have heard old folk reminisce about the jubilant crowds on VE Day in 1945; I imagine that the people with me now might have jumped into fountains likewise, if circumstances had permitted – in other words if they had been in Trafalgar Square, England, instead of hanging upside down from magnetic soles in Sgombost Arcade, Sgombost, Arroung, Birannithep, Hudgung, Kroth.

Whatever great good thing had happened, it was so great that my mind could not hope or desire to absorb more than a sip at a time, but physically I was restless because I had begun to suffer from a headache – a healthy, though painful, consequence of having attained a sane and continuous awareness that I was the wrong way up. I urgently looked forward to being rightly positioned again. And from the restless and impatient motions of the people around me I could sense that they likewise had de-adapted and were keen to resume upside-upness. It’s not easy to rush around enthusiastically hugging people when every step must involve a click and a clunk of a metal sole, off and on to a magnetised surface of a ceiling. By the look of things, though, it would take quite a while for the jam-packed arcade to be cleared and for everyone in it to find normal paths and floors where a person can walk with head up and boots down.

Relief, however, came sooner than I expected.

While a loudspeaker boomed out radio announcements, I strained to make out the words amid the general hubbub. I failed to catch the meaning, but a plump girl close to me said, to me and to others, “Hey, they’re declaring a public holiday,” and a young man on the other side of her said, “Good, maybe they’ll do an underdown, yeah, you know, I bet they do!” I said, “What’s an underdown?” but nobody heard me. I didn’t mind; I was happy, for in the midst of others’ evidently sane happiness I was able to trust and believe that understanding would come later.

Cries broke out: “Woo-hoo!” “Hey-oo!”

A central strip down the arcade’s floor – let me refer to that ceiling from which we hung by our boots as a “floor” for a little while longer – suddenly glowed bright orange-pink as though its cool metal had switched to being incandescent. The “underdowning” had begun.

I was not standing “on” that glowing central strip, I was half-way from it to the side, but I was jostled as those who were “on” it hastened to shuffle across its boundary so as to get “off” it. I heard a few squeals of delighted alarm, a few more Woo-hoos. None of the folk around me were deeply scared, and so neither was I.

As soon as the central strip was cleared, a spectacular change occurred in its glowing surface: it split down the middle in two long flaps and disgorged a colourful torrent of balloony and cushiony shapes, that “fell up” (really, down) to the curved arcade “roof” below. Renewed cheering greeted the sight, and my own lungs bellowed with the rest in sheer jollity and wonderment, as the curved base below our heads filled with the bright new shapes, as dramatically as a dry river channel may receive a bursting flood. But what was the aim of all this? Oh – oh – I began to guess, and to feel that my boots’ attachment to the magnetic surface above me was most insecure. Visions came to mind, of a current switched off, and of the whole crowd of people plunging – surely, though, the authorities wouldn’t do that? People would break their necks, wouldn’t they, cushions or no cushions – or they’d tangle on the way down and injure each other… I did want to stand right way up, true, yes, positional reform was certaintly desirable – but not to be pitched into it the hard way. “I’m only a visitor,” I wanted to say, “not tough like you frontier-guys.”

During the next few moments I found out that the Arroung authorities had more sense than I had given them credit for. First, the glowing central flaps closed. Then their colour changed to a lambent green. “Yee-hee! Go! Go!” shouted many voices as lateral slits opened across the glow where the single lengthways split was no more, signalling the underdown’s second stage, and dozens of narrow transparent curtains descended, unfurling at a slow pace. The crowd knew all about it; knew what to do. Everybody surged towards the curtains, which, I saw, were provided with pockety grips and loops and rungs. The more cautious folk attached themselves to these with their hands and boots, and began a leisurely ride down towards the cushiony and real floor. Exuberant types, on the other hand, who wanted to jump, made use of the fact that the glowing surface was now de-magnetised. They placed one boot against it and clicked the other one away, so as to plunge with many a “Yeee-hoooo!” into the bouncy mass below. Yes, below. I could use the words “up” and “down” and “above” and “below” properly now. What a relief. And which way should I descend? Boisterous jump, or sedate ride? I wasn’t about to spoil my new life with a broken limb. I seized me a moving curtain and took the slow ride down.

It probably took me over an hour to lurch and wade through that festive throng. Most of the folk on all sides of me seemed in no hurry at all to get out; they were content to horse around among the bubbly cushions, to flounder about like children on an inflated plastic bouncy castle. I could empathise with them, for their headaches had disappeared, like mine, and they, like me, sensed overwhelming relief at the snap destruction of something big by something yet bigger; yet though I was quite happy that this Sgombost Underdowning had been added to my life’s list of colourful experiences, my keenest wish was to get home and vegetate for a nice long while in my room in Mrakkastoom College – so where the krunk (I muttered and panted) was the main exit? Eventually it became visible and near enough: I had almost traversed the length of the inverted “arcade”. At that point I noticed the small quiet man who had accompanied Nolan. He wore a determined expression as he grasped my arm and pulled me towards one of a line of exit doors – a perpetually revolving glass pane. His jaw and lips moved. I replied, “What did you say?” – and my words, like his, were lost in the racket which I had hardly noticed till this point. Then we were through the door, and the noise was diminished.

The feel of firm floor under my boots was as welcome as if I had just forded an outsized river. I staggered with exhaustion.

“We’ll git you home, Wemyss,” said the man.

“Ha – thanks – music to my ears, that,” I gasped.

“Sit down.” We were in a moderate-sized office, with filing-cabinets and other pleasantly boring things – even a monitor screen and keyboard. I sat at a desk while the man tapped something on the keyboard. He then sat back and said, “You won’t hev long to wait. I rickon, Wemyss, that we Arroungians owe you an epology.”

I considered this. “I suppose you do,” I agreed. “But never mind,” I continued inanely, quite disinclined to pursue the matter. As far as brain function was concerned, I might as well have been drunk. “Who are you, by the way?”

“Doctor Miguel Keller-Frack. Not M.D. kind of doctor; I’m just a PhD, you know.” He swayed as he spoke and I realized he too was tipsy from the “underdowning”.

“PhD – er, in what?”

“Psychology. At least thet’s the name on the parchment. But, aaargh – ” and he spat on the floor and I jerked back a bit, momentarily shocked – “if you hed to live in these parts I could edvise you on other names for it. Mintal pollution, for instance. The psychic iconomy hivvily polluted…”

“What a shame.”

“Yis, it’s a shime. But things are going right now, thenk goodness, only, we must now face the fect that we made a fool of oursilves. I suppose we owe you an epology…. but no, I rimimber you just sid you don’t need epologies….”

“That’s right, I don’t. What’s the point of them? You people didn’t know what you were doing, did you?”

“Yis, hmm, but how did we git into thet state? Thet’s what needs ixplenation….”

I blew out my cheeks and windmilled my arms and said, “Explanation! Explanation! I’m not gonna bother to look for any explanation ever again! I’m gonna flop on a couch, big-time.”

“I’ve heard a bit about you, ectually. Rickon you’re quite insightful in your way. Make a good ditictive…”

“Oh yeah?” I snorted. “More like, I’ll be like the cop in Crime and Punishment who knows he just has to wait to get a confession. Yeah, I’ll sit back and wait for the universe to confess.”

“That’s an idea,” nodded Keller-Frak. “Yeah, and I ixpict it will.”

The phone rang.

He snatched it up. “Keller-Frak. What! Rilly? Tirrific!” He banged it down and said, “Bus riddy to take you home – and I ken eccompany you.”

“Good work, doc.”

“More ‘civil servant’ than ‘doc’, I must confiss – ilse they wouldn’t hev given me this time off. Spicially es the underdowning will hev strained the budgit alriddy. Lit’s git going.”

*

“Bus” turned out to be Arroung slang for special first-class train. When we got on, Keller-Frak and I had the entire carriage to ourselves, such was the anxious determination of the provincial authorities to compensate for the mistreatment of Vic Chandler’s nephew. For that was my importance: I was nephew to the man who had broken the influence of the Slimes. The man who, at one sudden stroke, had transformed the psychological atmosphere of the whole country.

I neither understood what the Slimes’ influence had been or how it worked, or anything about the nature of the trick which Vic had just pulled off, but – the notion came as the sloshed dizziness of the underdown wore away – maybe it was time I asked?

Yes… despite my declared refusal to seek explanations (which were bound to be strenuously exciting, and I was bone-weary of adventures), it might for politeness’ sake be a good idea to show some curiosity.

Therefore, although my deepest inclination was simply to relax and sun myself in what you might call the deck-chair of ordinariness, or the magic of humdrum, trusting that all truths would emerge to set up their own deck-chairs around me in their own good time, I nevertheless asked:

“Say, doc, what exactly has Uncle Vic done?”

“Done? Heven’t you heard?” asked Keller-Frak, lifting his brows. “He’s found a new star.”

My underdown-dizziness, as mentioned above, had mostly worn off, otherwise I might have taken this literally and asked something like, what star, what part of the sky is it in, can one see it from here? As it was, the workings of my mind were a bit more subtle by this time. The ‘star’ thing must be a metaphor! And therefore – oh bother, I now thought, I had better make some effort to guess what such a figure of speech might turn out to mean, in this situation. Of course I could just simply ask Doc, but in me persisted the habit of belief that I must always try to be clever, one step ahead in order to survive. So come on, brain, think it through. Whatever stopped the Shoggoth, it can’t just have been Vic literally discovering a nova in the firmament! But then I made a discovery of my own, which was that the lump of grey matter between my ears had gone on strike. It remained more or less inert while my ears sponged the sounds of the train:

larrup-a-pate,

cough-up-a-sun;

hollyhock soup

sharp-on-the-tongue…

“A new star – that’s interesting,” I replied dreamily to Keller-Frak. “I heard that Uncle Vic had been given a post at the Observatory…” There, that would flush out the metaphor; would prompt Keller-Frak to say, no you dope, not a literal star, nothing to do with observatories…. My eyes flicked to his face, across the table from me, and then to the window and the passing landscape overhead, and I was pleased at the steady rhythm of my heartbeat. My brain was in gear again, its strike was over, and I sensed I was in a win-win situation, for the normal elements in life were threading together once more, and though I was doubtless in for a surprise – surprises must happen – it wasn’t going to overstrain the budget… metaphor, show yourself, I’m ready for you.

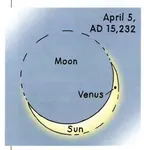

“He reported it to the Observatory staff,” said the doctor, “but he didn’t discover it there. I bit they’re kicking thimselves… anyhow, he’s got the glory. Imagine! There he was, on a stroll outside after that Collidge dinner, and he looks idly down at the night sky, and there it is, a blazing point of light in the constillation of the Plumb-Line – wow, must make a guy shiver, to make a find like thet. You’ll see it tonight, no doubt. Nova Perpindiculi.”

Sometimes on a lucky night you can actually dare a dream to go wrong, and you get away with this bravado because the dream doesn’t dare accept your challenge, because your will is strong enough to counteract the slippy tendencies that try to pull you towards the repellent regions. I had been proved wrong. The New Star was no metaphor. Never mind, be it so, let me be wrong again, I dare my head to wobble after bunkum so long as I can keep the said head down, I’ve coped with so much already, I can simply accept that the universe around me is a universe in which the discovery of a star can snap the Shoggoths’ control, never mind how! Vic is welcome to explain it if he can or alternatively he can keep it to himself; either way, my own life is on the up and up, as is proved by this train, that’s taking me in the right direction at last. Up! Northwards! No more downward-Southward journeys for me.

colicky shock

rack-me-again?

hollyhock soup

freshen-the-tum

Quite right, train, I’m taking my poisons in homeopathic doses from now on. And as for being racked again, no, the colicky shocks have had their day, hence the question mark, to which my answer is no, I won’t be racked again. The New Star – whatever it is, however it works, I shall trust it, and besides, astronomy is a science that has never done anyone any harm, unless you count those who have fallen down manholes or into ditches while preoccupied with looking up at the stars…. (Up at the stars: that was a nostalgic thought, reviving fond memories of the northern hemisphere of Kroth; or even of Earth.) I put my head on the headrest and settled back to enjoy my journey home.

*

Dusk had fallen when the train at last slid to a halt at Mrakkastoom Station – greeted by a dim multitude of waving hands.

By this time more carriages had been added at various other halts, and the term “special” no longer applied to this train. Keller-Frak and I were now far from being alone in our first-class carriage – in fact so many other passengers had crowded in, that many were standing in the aisle, and the Doc and I had to wait, in our seats at the window, for these folk to alight, before we could make a move ourselves.

Twenty-four hours had certainly made a difference to the level of population on Platform 1. Despite the lateness of the hour I saw dozens of children, presumably just alighted over on Platform 2 with their parents after a day’s outing; they must have crossed in this direction towards the station exit, but they weren’t progressing very fast, rather they were larking about, jumping, running, prolonging the holiday atmosphere, while their elders themselves were livelier than might have been expected after a family day out, a large proportion of them engaged in keen discussion, laughing or taking flash photos, with some dodging and fooling which nudged the scene towards the heave and sway of carnival. My gaze slid around, and was snagged within moments by the sight of Jack Petergate and Gedelly Sanand. They stood with a group of other students whom they had perhaps come to see onto the night train; my heart gave a flutter as I recognized Elaine Swinton; Prince Rapannaf of course was with her; they, and a bevy of girls including Lola Vannaig, whom I knew slightly, clustered around an engineering student, Trenton Rhind, whom I disliked (he had sniffed his disbelief of my story, when people had asked me about my experiences in Slantland and Udrem)... How was I going to get past this lively lot, and attend the longed-for haven of my college room, without being asked a lot of questions? The carriage was emptying, Keller-Frak had got up and it was now time for me to follow his example and to edge down the aisle towards the door. I was going to be one of the last out.

Pushing my way through a merrily impatient surge of incoming passengers, I came face to face with Elaine as she mounted the step up into the carriage doorway; her eyes went wide, she yelled over her shoulder, “Hey, here’s Duncan!” – and stepped back again.

I followed her out and stood on the platform while the ebullient crowds milled around me.

“And where,” asked Jack, “have you been?”

“South,” I replied, praying that none of them would question me more closely. “Nice to run into you folks – but hey, don’t miss your train!”

He looked at Elaine; Elaine looked at Rapannaf, who shrugged. Lola Vannaig said, “Who cares? There’ll be another.”

Trenton Rhind then startled me by a comment that was good-humouredly cheeky, instead of snidely cheeky as I would have expected from him. “Dunc’s the sort to undergo sympethitic nervous symptoms over frinds about to miss their train. Relex, cobber! Lola’s right, we’ll just git the nixt one.”

“Hev you seen the Star from here?” asked Gedelly, and my answer was drowned in the comments, “Come on!”, “Lit’s show Dunc”, “Yeah, lit’s view the Star!” I was caught by the arm and pulled along, but then another figure, a tall elderly man, meandered his way purposefully into my presence.

We gave him some attention, for he was Myron Hayton, Principal of the College, come to meet me, to take me immediately home, which was just what I wanted. “I’ve brought a pidickeb for you, Wemyss.”

Pedicab – yes, that sounded good. “Thank you, sir! I wouldn’t mind, at that.”

“Lit’s take Dunc to view the Star first,” insisted Gedelly. Lola echoed, “Star for starters!” Trenton Rhind joshed him, “Never mind your principles, Principal!” Myron Hayton’s plans wavered, crumbled in the face of this pressure, and he came with us, not to the pedicab-rank but to the ordinary entrance walkway, and was swept along it by our enthusiasm, to a point some ten yards or so from the station building. The only exception was Keller-Frak, who, rather than be drawn with the rest of us, whispered to me, “I must get on. See you in College, I expect,” and slipped away. Apart from him, we all flopped against the walkway-railing and bent forward and gazed down into infinity.

Lola pointed, “Look there, Duncan.”

Trenton Rhind said, “Diclination minus 38 degrees, Right Ascinsion thirteen hours twinty-five minutes, I think.”

But there was no need to have recited the co-ordinates.

In spite of the Nadiral Light the sky looked blacker than it usually did from Hudgung, and this has to be from contrast, caused by a new diamantine blaze against the velvety firmament. I drank the Nova-light, spellbound. Kroth’s sky had been rich enough before, but Nova Perpendiculi – Chandler’s Star, as history would name it – spat lances of brilliance that surpassed the coruscating beauty of its brightest rivals. I wondered whether it was brighter because it was closer, or because it was more powerful.

“Megnitude minus 9,” continued Trenton Rhind.

“Will-rimimbered, Rhino,” said Jack. “We don’t need an incyclopedia whin you’re here.”

Rhino? Could that silly name have caught on, which I had spitefully given him, after he had looked down his long disdainful nose at my stories?

After we had gazed our fill at the Star, someone suggested going for a drink at the station pub, and since we were all at the stage where such a suggestion is automatically greeted by “yeah, good idea, yeah”, we went. At the bar, Jack handed me a tall glass. “Rhino’s bought you this beer.”

“Uh? In that case – ” I shifted, to peer round to thank Trenton. It wasn’t hard to locate his six-foot-five frame of stevedore build. “Cheers,” I said to him, lifting the glass.

“Cheers,” he replied, lifting his, and added: “This Discoverer uncle of yours – I wonder what he’ll do nixt.”

“Who knows?” – and even as I thus replied, I had a vision of the countless effects of what his discovery might have already triggered in every person’s life, by shaking the consciousness of society, touching, rearranging; as in the erasure of the petty enmity between me and Rhind. “Impossible to predict,” I went on. “Uncle was quite a character, even back on Earth.”

“Ah, yes, the Dream of Earth. Can’t remember much of thet, it’s so faded now…. but say, wasn’t the rhino some powerful enimal, on Earth?”

“It was.”

“With a huge horn on its nose?” Trenton Rhind looked down at me interestedly as he spoke. “Hince the name rhino-ceros?”

“That’s it,” I nodded with a regretful grin. “You don’t have to rub my nose in it, though.” Suddenly we both laughed, as we each saw the plain good will in the other. “Silly of me,” I gasped, “to make such remarks when my life insurance wasn’t even paid up.”

“Ah, no, I’m gled I’ll be good in a charge,” he countered obliquely. “Think of it. A charging rhinoceros builds up momintum. Which will be needed. This New Star, you know, it’s made me feel punchy.” Acting out this feeling, he punched the air, obviously determined to do something mighty with his life. At that moment the station loudspeaker announced the arrival of the next train North, and Rhino and Lola and Elaine and Rapannaf took their leave. Jack and Gedelly were content to remain a while longer, as were Hayton and the driver of the forgotten pedicab, while I took my leave to head alone for the quietness of my college room, which beckoned to my gutted self.

Emerging from the station pub I saw that the platforms were still crowded. Well, why not, after all? Though under normal circumstances the healthy animation around me would have been excessive for this hour of night, it was quite appropriate now (I dizzily reflected) – now that New Star had broken the ice at the cosmic party.

Out the exit, onto the walkway, I plodded in solitary, happy weariness homewards towards the College, in the light of the few streetlamps which dangled from the overhead surface of Kroth, and of the many stars that shone up from below.

*

Though dog-tired, out of habit I looked in at the porter’s lodge, to see if any mail had been left for me.

The chap on duty cleared his throat. Carefully pronouncing his vowels, he proclaimed: “It’s good to see you’re back, sir. The Discoverer himself has been using your room. You’ll find him there now. He’s been waiting to see you. He’ll be glad to see you, sir.”

“Himself, eh?” I grunted. “Thanks for the warning!”

Without further delay I headed for C Staircase, and as I mounted its steps I met Doc Keller-Frak on the way down; he wore the intensely serious expression of one who has just been given a terrific job to do. His greeting was hardly audible as he passed me. Obviously, he had just had an interview with Himself.

I heard Vic’s voice as I pushed my door open and then I saw white and beige oblongs of papers and files scattered over desk, chairs, bed and floor. Uncle Vic was in the act of stooping to reach for a document while at the same time he was speaking into that rare thing, a mobile phone.

He turned to stare at me delightedly, muttered something to end the call and said: “Duncan, hello at last! Come right in!”

“You know, I think I will.”

“Um – yes, it’s your room, isn’t it? Sorry. Been snowed under with this stuff – had to tackle it while I waited for you.” He began to gather up the papers. “You wouldn’t believe… but never mind, I can see you’re exhausted. Maybe tomorrow will do.”

“Do for what?” I exhaled, settling upon a cleared chair.

He gestured at the mess. “I am suddenly the focus of more pressure than I can comfortably handle. I need an intelligent side-kick. Someone I know and trust, someone… but you don’t want to think about it now, I can see. Just give me a minute or so to get these reports in order, and then I’ll leave you in peace. We’ll talk tomorrow.”

I shook my head. “What is all this stuff, anyway?”

“Can’t you guess? The government has gone into overdrive, in the effort to keep tabs on what’s going on. They roped me in naturally – how could they avoid it, I’m the great Discoverer! – and, aha, I roped in Keller-Frak. You must have seen him going down the stairs; did he look excited?”

“He looked important, anyhow.”

Vic nodded, and snickered. “I told him the committee would be named after him, if he played his cards right! The Keller-Frak Committee! Better than the Chandler Committee – which would be a bit much after Chandler’s Star… don’t want to overdo the Chandler this and Chandler that…”

“Uncle, I’ve never seen you look so happy. What are you up to, really?”

This disconcerted him for a mere split second.

“It’s more a question of what the world is up to. You know what I unwittingly did when I spotted that Star in the early minutes of its brightening, and spread the news? I unleashed a Renaissance. Overnight. I snapped something. I de-conditioned the world. I let loose a raging virus of awareness.” He flung his arms about as he spoke, cleverly pre-empting the charge that he was being theatrical… cleared a space and sat down on the bed, picked up a file, stared at it for a moment… tossed it away with a laugh. “And if you ask why, and how, and what does it all mean, I’ll whisper to you, don’t bother. The answer will peep out from inside us soon enough, or so instinct tells me. But meanwhile of course we’ve got to have a Committee, which will take a few months to report on the security aspect; it’s got to tackle a number of thorny questions: what happened to the aims of the Slimes, what were those aims before and after the psychological transformation brought about by the New Star, how exactly did the Star break their control, what was the nature of that control, what they’re likely to do next, what we should do to anticipate it, and so forth. My guess is, by the time we have that synthesized Report, popular action will have made it out of date.”

“Krunking heck, Uncle! I don’t know about all this. I’m done in. Just tell me one thing – why did it have to be you who spotted the Star?”

“Ah, you want me to brag about my Tycho moment? After the junketings of a Founders’ Day Dinner it’s natural to want a stroll outside to clear one’s heard; I ambled as far as the boundary of the College squelm,” (the walkable flat space,) “sniffing the night air, and I was just gazing down at the stars, checking how well I had learned the constellations of Kroth (I don’t know them all yet, but Perpendiculum, the Plumb-Line, is one that I had memorised) when I saw, as Tycho saw in 1572 when he gazed up at Cassiopeia, a brilliant point of light where none ought to be.”

He paused, re-living that unique, awesome instant of discovery.

I, too, was quiet. I possessed enough imagination to share his moment of tremendous touch – the touch of cosmic change. The sky unanswerably is the deepest face of the real, and when that face changes expression, our spines tingle, whether or not we have theories that can explain the event.

I found my voice again.

“You haven’t answered – ”

“Why it was I? Well, for that matter, why did nobody at all (in the West) record the tremendously bright Supernova of 1006? Eh? Quite a thought, that! Not one single person…”

“No Vic Chandlers in medieval Europe, evidently.”

“Yeah – you got it, that’s the point – I’m not conditioned, never will be; whereas back then, all the educated folk had been conditioned by their culture into the belief that nothing changed among the ‘fixed Stars’. Their beliefs restrained their eyes from seeing. Similarly here in the Krothan universe, though no doubt for different reasons, folk had got used to taking the unchanging sky for granted – though here with less excuse, for their own theories have always supported the idea that new stars occasionally appear. But perhaps the Biris were bound to be less courageous than the Toplanders in this respect. I mean to say, it’s hard enough to get used to a yawning sky beneath one’s feet, let alone an active yawning sky. And talking of yawning, I’d better shut up; you look like you need to go and sleep like a log.”

“I’ll most likely wake like a log, too.”

“No, you won’t. You’ll be fine tomorrow. Raring to participate, alongside me, in the making of history. Sleep on that.”

*

I woke muzzy and comfortable, with the pleasant knowledge that I might go back to sleep if I wished, despite the fact that it was after half past nine. First, though, I lolled cheek to pillow and stared at the door. Specifically, at the carpet near the door.

No note had been pushed through.

An excellent sign, that clear bit of carpet!

Suddenly hungry, and imbued with the sparky conviction that this was going to be a cracking good day, I swung out of bed and decided to have a go at getting to Hall in time for breakfast, for, what with all the overnight guests, the College would be bound to stretch breakfast hours till ten, which meant I was in with a chance. And while I washed and threw on some clothes, and hummed in sheer joy at the clear floor (for I had half-expected some pressurizing note), my mind budgeted in advance for the gumption I might need to resist other political Vic-moves. He might be waiting to catch me at breakfast or he might lurk a bit later on at the porter’s lodge… or he might button-hole me here in my room… Well, just let him try, I thought confidently. I am not going to get roped into his Committee and that’s that. They can make their history without my help. I meanwhile shall peacefully read a book while eating my bacon and egg. Heaven, here I come.

At the entrance to Hall, I looked in and saw him seated with three other fellows, one of them Doc Keller-Frak. All four of them, I was glad to see, seemed occupied in serious discussion, which would give me an excuse to leave them to it, and to take a table far apart from them. Problem solved, I headed for the serving-hatches.

“Hoy there, Duncan!” said my uncle’s voice behind me.

I turned. “Good morning, folks.”

“Go for it, lad – full English breakfast, a universe away from England!”

With my head almost split with a grin I could not resist, and with a hand raised in general greeting, I replied, “I’ll go for it, don’t you worry!” And go for it I did, the whole heaped plateful, and brought it to where I wanted to sit, several tables away from the history-makers. All my experience of Vic’s style and tone suggested that he had signalled to me, that I need not concern myself with whatever decisions his group were thrashing out; in other words he had relented, and there’d be no pressure…

After breakfast I had an inspiration: I would go for a walk in the country. No reason why I shouldn’t spend the day out. Despite recent interruptions, I was well ahead in my studies. Sunshine, fresh air, Nature, would slake my thirst for peace. I packed a small rucksack and headed for the country exit.

As though he had foreseen and read my mind, there he was, lounging against an ornamental sculpture, his chin on his chest as he gazed past the postern gate and down into the blue sky. Well, let him make one last attempt, I thought good-humouredly. I was old enough to stand up for myself, wasn’t I? Besides, as fate would have it, a smaller figure, further off, caught my eye – though hardly more than a pale blob far removed along the rope walk that led away into the dangling brush and woodland, her features were deducible to me, from her line of face and dark plaits – and I thought to myself: this is a bit of luck; she’ll make it easier for me.

I can tell him I’ve got a date with her. What’s more, I can hope to make it true.

“Mornin’, Uncle. Sorry, don’t have much time to talk right now. Need to catch up with Anne.”

“Ah, that’s the ticket,” approved Vic, quite happily. “At the dinner I noticed you chatting to that nice little number. Looked like there was some good chemistry between you.”

With a burst of laughter I said, “Don’t mention chemistry in connection with Anne! It’s the bane of her life, from what I gather. In fact, our two hearts beat as one, with regard to chemistry exams; only, unfortunately, her ordeal is still in front of her.”

“Well, you go on and take her mind off it for a while. You’ve decided to leave the world to me, I suppose.”

“Why not, since you’ve got it eating out of your hand?” Indescribably relieved at how the conversation had turned out, I was minded to prolong it just a bit more, till Anne had receded out of sight along the rope-walk, for if then, when I caught up with her, she were to tell me to clear off, Vic would not see the contradiction of my claim that I was supposed to meet her.

He rose to the bait. “I haven’t quite got everybody eating out of my hand. You know, back on Earth I used to hear plenty of twaddle about the so-called problems of success; about how fame and fortune can cause stress which some people can’t handle. My attitude to all such drivelling subtleties was: I’d be quite happy to swap problems with one of those dopes, thank you very much! Well, now it’s happened. Success with a capital S has come down on me like a ton of bricks. That’s why I really could have done with your help. But only if the task is right for you.”

“It isn’t. Sorry. I know my limitations. I’m…”

“You don’t have to struggle to say it. I believe you – for now – and I shall cope without you, don’t worry! Come what may, I shan’t waste this opportunity.”

“I bet you won’t. Make hay while the Star shines, eh?”

It was meant to be my parting remark. He had the last word, however. Vic the Scientist superseded Vic the Manipulator and he was so serious and interesting, that I was tempted to listen:

“This star’s shine is here to stay; we’re not in Earth’s universe here, remember – here a nova is a real new star, not an old star that has blown up…. A real new star, with its lifetime ahead of it. And probably orbiting an equally new planet larger than itself… Yeah, the quantum foam is on a macro scale, in this universe, where not mere virtual particles but entire suns can pop into existence. You’d need cable theory rather than string theory, here. Hey, I’m delaying you. Don’t keep Anne waiting. ’Bye for now.”

I waved as I went out through the gate. I had torn myself away. I had escaped.

*

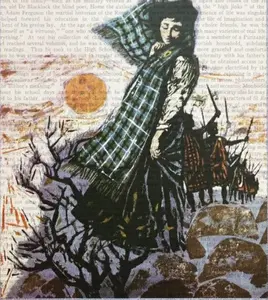

A wedge of genuine countryside extends into the leafy and suburban area of Mrakkastoom where the College is situated. This is a boon for fellows, students and staff whenever they are in the mood for a ramble: the wilderness is easy of access, via the rope-walk that runs from the postern gate, through which I now followed Anne.

The rope-walk is of the simplest kind, two ropes, one slung above the other, one to hold and the other to walk on. They are supported every ten yards or so by steel staples which fix them to trees or posts, and the Biri Pathways Authority inspect these overhead ‘downrights’ regularly to check that every single one of them is secure. Much of the southern hemisphere of Kroth is threaded by the cheap and efficient rope-walk system, and by this time I was so adapted to life Down Under that I could wander its rural routes without a qualm. This was just as well for a country-boy-at-heart like me. If you’re shaped like a normal human being, the rope-walks provided the only practical means of taking a stroll in woods or fields, where the sky and you are beneath them.

This particular path, in its early stretches, had become so familiar to me, that the inversion of sky and ground hardly mattered any more. Not that I was unaware of the truth; I wasn’t in that madly adapted state, which at Sgombost had made me confuse the reality of up and down. It’s just that I had reached a quiet accommodation with the facts, a compromise that allowed me to appreciate a landscape for what it contained, no matter which way up it happened to be. The colours and shapes and sounds of Nature could rejoice my heart whether they were grounded above or below me. Today as I approached the first bend in the path I heard birds sing roo –weet – doo, kik! – roo – weet – doo, kik! as if to celebrate a win-win-win situational melody, a life gone right like mine, what with my escape from the orbit of Vic’s ambitions, the promise of a pleasant ramble, and the chance of a meeting with Anne Belormen.

Then, rounding the corner, I came into Anne’s presence sooner than I had expected.

She had not gone much further ahead. Instead, she had stopped by the wayside at a modified hammock-bush, a large and complex one. Its seven-foot leaves, slung between half a dozen woody stems, were evolved to catch moisture and nutriment from above, but human agency had cleaned some of them out and lined them with cloth, and in one of these Anne sat cross-legged with her revision notes around her.

She looked broody and attractive, her nose in a book, her mouth a thin line of concentration; a picture of huggable earnestness.

I exclaimed, “Hi! That’s a nice nest!”

She lifted her head and smiled at me across the three-yard gap that separated us. She, or somebody, had rigged a side-branch of the rope-walk to cross that little gap. It looked well enough done. College must have checked it.

“Hi, Duncan. You see I am trying to git the bist of both worlds. Rivision – git the work done – but git it done out in the sunshine.”

“Education plus Vitamin D.”

“Some of us hev to work hard,” she went on, looking at me with a mild tinge of resentment which I did not understand. “You don’t hev any brothers or sisters, do you?”

“No,” I confirmed.

“Well, believe me, if you hed a younger brother and an older sister, both cliverer then you, you’d know it was no joke always heving to try to ketch up with thim.”

“I’m frankly amazed to hear you talk like this,” I protested. “Anne, you’re going to have your own type of success….”

“You sound like my mother,” she replied dismissively. “I know all thet stuff about ixem succiss not being iverything – ”

“Well, take notice of it, because it’s true!”

“Yes, it’s all viry will someone like you saying it. You niver hed to swit to pass an ixem, I’ll bit.”

“Hmm,” I replied uneasily. “I’m not so sure about – ”

“And anyhow, in this new era that your uncle hes plunged the world into, it’s going to be more nicessary then iver to be someone.”

“Now whatever is that supposed to mean?” The conversation had lurched out of my control. Ideas going off like squibs. Not what I wanted right now.

“Don’t you sinse it yourself?” she asked.

I made my voice firm: “All that I sense is that it’s a beautiful day and you and I should forget all this head-banging stuff and go for a walk. I’ll share my picnic with you, and…”

“Sweet of you, Duncan, but I must git on. Sorry. Leave me to my work, please.”

“To try to ‘be’ someone when you already are someone!”

“Leave me alone, Dunc,” she insisted. “’Bye-’bye,” and she smiled and waved, coaxing me to go away.

“I obey,” I said, “since I haven’t exactly managed to sweep you off your feet on this occasion. Oh well, there’ll be other sunny days.”

She allowed that to be the last word, which cheered me. I know what I’ll do, I thought: next time I see her I’ll definitely make a date to go over my revision techniques with her. Last time I offered that, she seemed keen, and since she appears to think I’m some sort of academic whizz kid she can’t very well change her mind about it. And once I’ve fortified her in that way, then we can go for a picnic. Meanwhile….

The path beckoned. Let swots be swots, I would make this a day off for me, taste the wandering breeze, the unpopulated vastness echoing with the song of birds, Nature’s spiritual lullaby, which with any luck might smother my usual twitches of foreboding.

*

Definitely,

the way to get the most out of it was to accept this landscape on its

own terms, and so to appreciate its shapes and hues and movements and

sounds, without the shadow of “up/down” prejudice.

So, as I moved

forward through a region of brittle light-brown bushes, interspersed

with the frozen downward lunge of dagger-shaped trees, my eyes often

sought the Eaveline (also called the Urizon), the line between land and

sky. I sought it in order to help keep my balance, for as a reasonably

experienced hiker I had taught my instincts to argue: “There’s the line

that divides two splendid areas, both being fine ingredients for a view,

and you needn’t quibble about which should be above and which below.”

Occasionally a drop or two of water plopped down onto my cap. Water

descends through Kroth in various ways. Some of it trickles through the

main body of the planet via sequences of caverns, most of which have

never yet been explored; some additionally aseeps through the giant root

systems of the matted grasses that cover most of both Yeyld and

Hudgung. The city of Mrakkastoom is sufficiently far South for the

shallow overhead Slope to prompt much of this water on its arrival to

drip straight down into the sky. Each “plop” was to me a whispered

suggestion, far greater than words, a reminder of the enormousness of

the world above my head. I was vividly reminded of the thousands of

miles which that water must have percolated from the lake of Nistoom at

the North Pole, and of my own equivalent journey. In the Krothan cosmos,

gravity sure gives a universal thumbs-down. Still, whatever creature

you are, you don’t have to take the last, never-ending fall. You can

evolve techniques of safety. Beautiful instances of adaptation

surrounded me. I saw a flock of dangling purple-brown inchworm shapes,

grazing in a meadow; they were smaller relatives of the steeds that had

brought my companions and me down across Slantland. I saw, and approved,

the way they avoided the groves of filix trees, which reproduce in a

manner dangerous to passers-by: every so often the filix will fire seeds

up into the ground with a report like that of a rifle. This was the

season to hear such shots, perhaps on average one every half hour or so.

The sounds were easily blunted by the surrounding peace. Also in

evidence were plenty of kannaweejers, birds with legs growing up from

their backs: I watched them periodically let go of the ropey grass,

allow themselves to plummet helplessly some distance down into the blue,

and then with a sudden flutter seize control of their fall and take

wing. All this will have to do, sang a refrain inside my mind. Have to

do, have to do. All this will have to do. I answered back: yes, that’s

fine; give me peaceful days, quiet walks, more meetings with Anne, minor

success leading perhaps to a fellowship of the College, and it

certainly will do. The inner voice did not contradict me. It fell

silent.

The rope-walk had brought me to a point on the edge of an

overhead meadow, which sloped down to my left. To my right ran the

boundary of a wood. The dangled trees were gnarled here, like oaks;

their leaves rustled in the breeze and some of their branches shook and

swayed with the activities of nesting birds. And then I perceived a

different category of disturbance. A rat-a-tat, followed by a pause,

then more frenzied tapping, accompanied a blurry shiver on a slender

branch.

I edged closer to look.

The blur resolved itself

into an exhausted squirrel, or similar animal, which clutched a

much-frayed portion of the branch. Then as I watched the fit of tapping

resumed; the poor creature seemed to be attacking its own branch, or

trying to shake it into some different shape; the spittle that sprayed

from its mouth visibly darkened the splintered wood.

A word came to mind: snyupilia.

A disease, which I had occasionally heard of and read about, but of

which I had never witnessed any instance before now, outside of books

and articles and learned speech.

I dared not approach, and in any

case I could have done no good, so I simply watched and waited for the

end. It came within another half minute: the squirrel in its final

flurry of terror bit through the last thickness of branch.

So, into the void tumbled one little statistic, one snyupilia

victim, leaving a broken wet stump and the sympathetic trickle of sweat

down my back. I took a deep breath which ended in a shudder –

And then a voice behind me spoke.

“A fine day, but there are always some losers.”

So relaxed was the voice, so normal and conversational, that as I

turned I was sure I’d see some stroller from college. He might, I

guessed, be a fellow or mature student, the sort likely to make that

kind of philosophical remark.

If my wits had been keener I might

have gained some doubts from the direction of the voice, for it came not

quite from the rope-path but from a little way to the side, out under

the meadow. Unlikely terrain for a normal-shaped human. I knew this, but

I only applied my knowledge when my eyes met the dangling face of the omong.

He didn’t have to stick to the path! For the second time in my life I faced one of the ‘spider-men’.

With a compassionate smile he gazed past me as he dangled from the

grass. His torso hung securely from the four hand-ended limbs which grew

from his back, his entire stance expressive of perfect confidence,

perfect adaptation to this hemisphere of the world. Always three hands

to grasp the grass while the fourth advanced to a new hold – he could go

anywhere. Abashed at the sight of him, I was sharply conscious of the

millions-of-years start he and his race had over the rest of us, and at

the same time I sensed how I might raise my game to match the demands of

this encounter.

I replied in a small but sure voice:

“Fine day for a walk, yes, but, to tell the truth…” (Make him guess;

draw him into my game. But am I daft, to match wits with the wisest race

under Hudgung? No, not daft – just having a really good day.) “…I had

an extra reason for going out this morning.”

“You bipeds,” chuckled the omong, “must have your complexities; we naroabar are comparatively simple.”

“I too,” I said, “have played a good simple game today, so far. I wonder if you’ve heard of it: Pass-the-parcel.”

“Biped culture is familiar to me.”

“Good, so you’ll understand my figure of speech.”

“The ‘parcel’ being….”

“An incredible, tightly-wrapped anxiety.”

“I did have the impression that something was bothering you.” The bland

perfection of the omong’s standard, neutral English might easily mask

disapproval or impatience, and so deprive me of the signals I would need

if I were to read his mood; therefore I must play extra safe and not

witter. Just be blunt, polite, dignified, humble, fearless and tactful

at the same time. That was the way to seize this splendid opportunity.

“I confess,” I began, “it’s clear to me now, that I wandered out here

in the hope that I might find one of you people. But this is only the

second time ever, that I have spoken with an omong, so I am not sure of

the etiquette…”

“None exists,” said the omong. “Just speak your mind.”

I was encouraged to confess more.

“A morale

game, pass the parcel from moment-to-moment, postponing the opening of

it, while I carry it serenely, shunting it along hidden inside me,

because I would have hated to open it before, seeing as I don’t want to

get locked up as a loony.”

“None of your biped worries are necessary here.”

“Yes, quite, that’s the point – you,

I know, will understand. I can unwrap the parcel neatly now, offload it

onto you without spoiling my nice day off, and then go my way in

peace.”

I paused for breath and to summon more moral energy, for

it takes some stuffing to denounce one’s own flesh and blood, even if he

might be planning Armageddon.

“My closest relative,” I went on,

“and in some respects my best friend, who has been a good guardian to me

after my mother’s death, a fine and decent man in every personal sense…

I am referring,” I continued, “to my uncle, Vic Chandler – the

Discoverer. That’s one title he’s gained. I could give him another –

Avalanche-Maker.”

“Indeed?” said the impassive spider-man. “And the story behind that?”

I was encouraged to narrate the true account, set in Tokropol,

Slantland, of a capture and an escape carried out at terrible cost. “You

see,” I finished, “I probably owe him my life, and I esteem his

brilliance as I should, but politically he is a man whom I fear above

all others.”

“Biped politics?” mused the omong, with laughter in his tone.

“No, not really – I only use that word because I can’t think of the

right one! In fact, ‘politically’ is a term so inadequate as to make me

laugh in despair – my sinking heart tells me he’s a world-wrecker.

Universe-wrecker, even. Cosmo-political, if you like.”

Courteously, the omong spoke: “How, may I ask, is such a statement to be believed?”

This inevitable question left me stumped, for in truth all morning so

far I had had nothing more definite than wormy masses of ideas which

bored through me leaving tracks of disquiet, and I realized I was going

to have to admit I had no answer. “What can I say? Nothing clear enough;

let me only say, I strongly suspect Uncle Vic had a hand in putting an

end to the Dream of Earth, and I likewise suspect he may do the same for

Kroth. Don’t laugh at me, Farambolank.”

“I am not Farambolank, and I am not laughing. I am Afraar-sif-reyad-sif-moonamast. Call me Afraar.”

I pressed a hand to the throb in my temples. “No, of course, you’re not

Farambolank. I’m not thinking straight. Farambolank was the omong whom I

met thousands of miles away from here, up in Kletterweggle. The member

of the welcoming committee, on my arrival under Hudgung. What’s the

matter with me today? I’m witless.”

“You’re simply more tired than you realize, Duncan Wemyss.”

I had not told him my name, but it was pointless to register surprise;

the omong outnumbered and surrounded us, they doubtless studied us and

knew us inside out… What really irked me was my childish brain-error in

giving him the name of the only omong I had met before. As though

thousands of miles of distance did not matter; it really was the sort of

assumption a child might make in writing a story – someone crash-lands

on Mars; very well, to rescue him/her you just head for Mars! Anywhere

on Mars, you’re bound to be in sight of each other… But he was right, I

was tired, suddenly aware indeed how cosmically tired. Glad, though,

that in unburdening myself to this omong I had at least salved my

conscience. The next move was up to him.

“If you will consent to wait another minute or two,” continued Afraaf, “you probably will meet Farambolank.”

“Eh?” I felt the mental reins slipping further.

“Most of the time he lives near here. Rartlamar, my wife, has gone to

fetch him. She had the idea that he might wish to see you today. – Ah,

here they come.”

At this point I completely gave up; it was obviously not my day for judging probabilities.

Two dangling forms appeared across the meadow and swung towards us,

hand over hand over hand over hand, while I watched in a stupor.

Presently the four of us gathered to exchange greetings, and I stared at

the omong woman’s swaddled torso, and then looked away, hoping I had

not been rude. I’m sure I needn’t have worried. They were overwhelmingly

leisurely people, always mildly pleased at something or other; after a

few pleasantries Rartlamar and Afraar withdrew, and I was left to face

Farambolank alone.

He said, “We meet again at last. You did not have much to say the first time. But now, I take it, you need advice.”

“Advice!! I’d like to think that was all. Fact is – I have grown to

love Kroth; and surely, this hemisphere of it is more yours than mine.

Hudgung is your land.”

“And so it will continue to be, for as long as Kroth lasts.”

“With my uncle on the loose, that might not be long. What place could

there be for your kind if Earth came back, eh?” But these wild words did

not sound convincing, not even in my own ears. I had said my say, had

voiced my vaguely colossal anxieties, and by the lack of any answering

spark to confirm them, had been effectively reassured. The day had been

saved. It had started off well enough, only a bit jittery and haunted

like a strong man slightly bothered by a heart-flutter, and now the

haunting was over and with even greater lightness within me I could

resume the enjoyment of my walk in the sunshine. Heigh-ho for merry

England, or rather, merry Birannithep! Of course, I had made a fool of

myself. But then, the omong were welcome to think I was a loony. We

bipeds were probably all children to them. Daft little children….

Farambolank spoke once more, and his words wrong-footed me delightfully again, and eased my conscience more than ever:

“Let us suppose for the sake of argument, that Vic Chandler succeeds in

resurrecting the Dream of Earth. Indeed, we also suspect that this may

be his intention. Fantastic to think that one man might accomplish such a

thing; yet, at a sufficiently pivotal point, anyone may move infinity….

but in any such case you may rest assured, that Kroth will not cease to

be. Remember, the Earth cosmos is a higher energy state, a construct of

the excited mind, that comes and goes in waves; Kroth as the ground

state meanwhile persists, the indestructible basis of reality.”

Oh, how I wanted to believe him! He was the sage, after all. He must

know what he was talking about. In which case, nothing that Vic might

possibly do could destroy my beloved adopted world. My blood fairly

fizzed in relief.

“Calm down,” the omong said as he watched me

shaking; then he came to a decision, swung forward and placed a hand on

my brow. My brain felt massaged into greater fuzziness than before….

“Go,” he said, “and enjoy the rest of your day off.”

So – too dazed to say goodbye, but I am sure he was all right about that – I went.

The path took me past some more meadows, into some woods and to an

ideal picnic spot where the path’s ropes detoured into a clearing and

ended amid hammocks that hung from the golden grass. Secured by the

safety clips provided, I sat and swung and sipped my thermos of tea, my

legs dangling over blue infinity.

I laughed suddenly. I said to

myself: “Well, cobber, what do you know, your gamble paid off.” I had

hardly dared hope, and yet, as it turned out, to judge from my happy

mood, the stuff that omong fellow spoke (the details were blurred in my

mind now) must have amounted precisely to what I hoped and prayed he

would say. Strange how hazy I had become, as to what the conversation

had actually been about…. some crazy stuff about Vic destroying the

world? Anyhow, since Farambolank and I had parted on good terms, it must

all be taken care of. And so I could live without uttering the sort of

unheard-of warnings that loonies get locked up for.

Time to

return to College, for the further comforts of supper and perhaps an

evening chat in the bar, or some paper-browsing and quieter chat in the

Common Room… I put my reusable containers back in my pack, and dropped

the disposables into the sky: it was intriguing to watch the

disappearing dots of banana skins, apple core, sausage-roll packaging

and used paper tissue, while I pictured their minuscule contributions to

the Nadiral Light; then I unclipped myself from the picnic hammock and

turned back along the path.

It was a peaceful, pleasant enough

walk until I drew close to the precincts of the College and came to Anne

Belormen’s little “nest” once more. Then morale got slippy again as I

saw some disarranged cloths, broken branches and no sign of Anne. At

once, fantastically woeful thoughts began to parade across my mind,

headed by the word snyupilia. But that was ridiculous; the

disease hardly every attached itself to humans, and besides, there

seemed to be no spittle on the branches, which had been broken already

for practical reasons in the construction of the nest. Ah, but human

society has its equivalents of snyupilia, said my realistic self. For

example: squartcho – the shock of sudden appreciation of where

one is, under Hudgung and on top of the sky. Despair – at any upset in

life – or any strong emotion can bring it on. But surely the likelihood

was, she had simply left the place without bothering to tidy up, and

gone off somewhere, maybe back to her College room?

But she did

not turn up to classes next day, or the next. I heard that some official

investigation was carried out, but my fellow students were mostly

silent in regard to her disappearance. It was only too clear what had

happened. One word was enough to sum it up. Emotion.

Student suicides were common enough in England – at any rate they hit

the headlines more than once, in my recollection. Here, in a cosmos

where it was fatally easy to drop into the sky, they must be far more

frequent still.

*

The authorities, in accordance with the law, waited a week and then pronounced Anne Belormen officially dead. Her funeral took place in the dangling University Church a couple of days after that. The turn-out was good; the place was packed. I sat as far back as I could, much of the time with my head in my hands, puckered face hidden from the rest of the crowd, as I grappled with perplexity and grief. Occasionally my eyes would stray to the little folded leaflet that had been handed to me at the door. It had a radiant picture of Anne on the front page.

The rector had some nice things to say about her in his sermon, and then his theme expanded to “Let not the sun go down on your wrath”. A good anti-emotion line, thought I, but a bit late for Anne. Hang on, though – sun going down? The sun goes across the sky here. Ah, but they quote from the Earthly Bible. For some reason, there is no Krothan Bible as such… The rector (actually, a Reverend Professor) went on to link the theme, very topically, with modern astronomy:

“Anne was one of many in the heightened death-toll of recent days. As far as we know, she let go while the balance of her mind was disturbed by pressure of academic work, but this does not necessarily exclude her from the roll of victims of the New Star, since the reason behind her reason may have been that her desire to compete was inflamed and made more desperate by the prospect of a radically changed world. Who knows which young person may next be at risk? Or older person, for that matter? We must reach out to help each other in these stirring times, bearing Anne’s fate in mind, so that she will not have died altogether in vain. As we know from The Tale, the dead must in some sense rise again, and perhaps this means that, once they are gone, we naturally miss them, the appreciation of them is rekindled in our hearts, and we love them more than before…”

A waffly Resurrection, thought I. Exactly what kind of Church is this?

“….No need to ask ourselves why the sky is dark here. No need to apply Olbers’ Paradox here. The sky is dark here because our universe is limited in size, and comes to a blank end after a few hundreds of thousands of millions of miles. But we know that this universe is not all that can be. We know that it carries within it the potential of something greater” (I sat up at this), “just as we carry within ourselves the potential of something greater, just as our Faith with its pretty stories carries within it the potential of something greater, which will one day extend to the crunchy facts of history. We believe The Tale cloudily, as a figurative embodiment of spiritual truths. But in that higher state of being, Jerusalem will be a real place, and Jesus will really have existed in the flesh…”

After this I realized that although the prayer-books and hymn-books, and the order of service in general, with its beautiful, contemplative liturgy, were similar to those in an Anglican church, I was probably going to hear something different when it came to the recital of the Creed. Sure enough:

“…We believe in the qualitative dimension,

The primacy of Personality as the Ground of one’s Being,

The demiurgic Logos,

The spiritual unity of all life,

The aspirational convergence of positive energies

And the eternal transcendence of every brief pattern in the temporal flow.

Amen.”

Afterwards, listening to groups chatting in the church porch, I shuddered not so much in the macabre sense of wondering who might let go next, like poor Anne had done, but rather in a larger quandary about what might happen to Biri society. I heard laughter – nervous laughter, and I wasn’t indignant, only sympathetic, when I heard someone quoting a joke by the comic, Korastiboon, who was notorious for daring to use the word “drop” on TV. I wandered outside, onto the wide magnificent Squelm (any continuous dangled surface upon which one can walk under Hudgung is a squelm, but they are all named after this one), and gazed at the University Church spire’s splendid downward jab into the blue. I was moved to wonder who its architect had been, who had expressed such a yearning challenge to the universe.

The service was truly over. In funerals where the bodies are available, the dead are dropped ceremoniously into the sky, but Anne of course had dropped herself, and so this last part of the ceremony could not be performed; all had been done that could be done, and I had that empty feeling of a loss finally confirmed.

Vic had kept clear of me during the service, but now he threaded his way through the dispersing crowd until he stood beside me, quietly.

“I’m very sorry,” he said, with unmistakably genuine kindness.

I shrugged. “Thanks. I hardly knew the girl, as a matter of fact.”

“Ah, but that doesn’t help, does it? You sensed what she might have been, to herself and you, and that is what hurts. I can imagine how I would feel, in your place. The same as you, I’d guess.”

“Uncle, what did you think of the service?”

“Ha.” He permitted himself a chuckle. “Real de-mythologised, or rather mythologised, stuff. Bultmann et al. would love it.”

I deduced that Bultmann must have been some trendy theologian. Well, it was something to talk about. I wanted to talk. “And what about yourself?”

“I rather fancy it too; it’s in my style. But it also serves a practical purpose. Blandness of religion is a way of avoiding passion. A matter of life and death, as we have been shown only too clearly….”

“Anyhow, you, er, tune in to… you, ah, dig this Biri religion?”

“Sort of, though I pity the motives for it. They avoid talk of sin and hell and judgement and stuff, which is fine by me, but they only avoid it because they can’t afford it. They’ve got to have something tepid. Can’t afford the emotion otherwise. You know, in seventeenth century England, or so I’ve heard, there were cases of people committing suicide because they thought they were damned….”

“Hey, that’s the most stupid thing – I mean, if you’re damned you might as well …. er…. enjoy the time you have left.”

“I saw you hesitate there. If you think you’re damned, of course you can’t enjoy anything. If you really believed you were damned, you’d go nuts. And here, you’d just drop into the blue. The line of least resistance to despair. How did we get into this cheery conversation, by the way?”

Meanwhile inside my head a decision had been hammered into shape.

The hammer-blows, voiced in my mind, assembled in chorus:

These people will always be weak, vulnerable –

As long as they are here –

So we must get them out of here –

And maybe he can do it –

I’ve heard there’s been doings

the past few days

at Lishom-Galeeg –

I shut out that inner chorus – I did not want to hear it – but I did want something to do...

“Er,” I began, “Uncle, about that job… as your assistant… Is it still on offer? Because…”

He saw my expression, he squeezed my shoulder and said, “Lad, you’ve got yourself a career.”