kroth: the rise

8: legislation

“Next time,” said the taxi driver, “I’ll take money off you – but this evening, my children would never forgive me if I didn’t get you to sign this, instead.”

We stood outside the cab. He had unloaded my bag; his outstretched hand held an autograph book and a pen.

He added, as I positioned to write, “Not too neat, if you don’t mind – they appreciate a good scrawl.”

I laughed and said, “I’ll scrawl anyhow, from exhaustion. Too tired to remember how I got here.”

“You got here in my cab… oh, but you mean in general.”

“I sure do,” I sighed. I squinted around me at a flat landscape of lawns, ponds, flowers, trees, and a huge car-park with a row of hulking vans, but no house visible anywhere. “By the way, got a card with your phone number? I may need you again soon.”

“No you won’t – not here,” he declared with a certainty which caused my wits partially to awaken. “You won’t need to carry your bag, either; just wait.” He got back in and his cab drove off into the gloom.

Gloom? Well, in a way. My senses told me it was evening, not only because I was tired, but also because the Topland near-daylight showed subtle gradations, according to whether the hidden circling Sun was below “this” or “that” side of the world; a distinction meaningless at the actual central location of the North Pole itself, but ever so slightly meaningful even a mile or two south of it – psychologically, at any rate.

Or perhaps that’s all rot; perhaps one just gets tired and so the imaginary gloom of an invisible evening filters into one’s eyes and mind.

The cabbie had obviously meant what he said, and I hoped that what he meant was that service would be laid on. Vaguely optimistic, I left my bag where it lay, and strode towards the vans.

The sense of evening intensified, and I found it comforting that some trace of a “real” night-and-day cycle exists, even if only as a pallid hint, on Kroth’s sunless crown. I summoned all normal thoughts to rally round. I needed to be in a trustful mood. I was taking General Faraliew at his word.

He had said, “Turn up whenever you like.”

“Shouldn’t I at least phone to say, when I’m on my way?” I had asked him.

“Absolutely not!” he had replied. “Don’t look so surprised – I’m in a position to know the rules at my daughter’s and son-in-law’s place! Believe me, it’s vital not to give advance warning of one’s arrival. Knowing what’s going to happen would only add to Melia’s stress; she lives in the moment, and so does Orville. You take life as it comes, at Marradale House.”

Yeah – all right – but where was the house?

The cultivated parkland which surrounded me would be a grand location for a stately home, such as I had imagined the Reaver-Sunch family would possess, but the only structures in view were the vans; six of them in a row, camper-vans they looked like, as I approached them. One of them had its side-doors open.

I drew close to this doorway, with the idea that I might call out, and I cleared my throat and began, “Excu….”

“Wowowo,” said a young woman’s voice, and a flappy white object, a clipboard which held some papers askew, tumbled onto the tarmac. “Krunk, snerg and damn. Oh, thank you, Opportune Person. This’ll teach me to carry too much at once.”

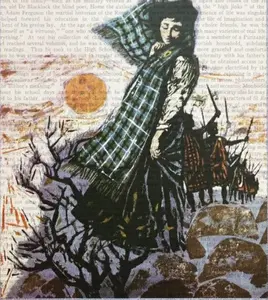

I had picked up the clipboard and handed it to her whom I knew to be my hostess, for the General had shown me a portrait, though this evening she looked more the hippy than the lady. Her hair hung loose in long tangly ringlets, her dusty jacket clashed with her red spotty dress which in turn clashed with her lumpy work-shoes. She was short and slim, probably in her mid-thirties, and wide-mouthed, attractive in a scatty sense. I felt awkward, wondering how best to frame my introduction, but only got as far as saying, “Er, Lady Melia…”

“Forget the ‘lady’ part, I say this not through inverted snobbery, just that ‘lady’ is boring on the ear whereas ‘Melia’ is kind to the ear, don’t you think? Now – let’s watch how they arrive!” She jumped down the step, just as I began to hear the sound of many engines. “Wish they could read a floor-plan – it would make life so much easier!” Waving the clipboard, she bustled past me, whereupon I turned to witness the arrival of a motorcade of vans. About a dozen of them rumbled into view round the corner of the driveway and into the carpark.

Melia waved, pointed, pranced about and got the leading five vans to park where she wanted them. Then she appeared to assume that the pattern had become obvious and the rest of the fleet could be left to take their places in proper sequence, unsupervised. So while another twenty-five juggernauts were positioning themselves, she whirled back to pay attention to me. I had gone to stand by my luggage, in case I had to move it. She jogged over to me and resumed:

“Notice, no battlements. Cedric Leonard – my boy, that is – he’s in boarding school – he wants a proper castle with battlements or, failing that, he wants ’em put on the vans. That would be something, wouldn’t it; crenellated camper-vans. I think he might regret it later if we were to do that, because people would be sure to laugh, and he’s so sensitive, can’t stand being laughed at. Hasn’t much sense of humour; takes after his father in that respect. Why am I telling you all this? I’m not so sure. People warn me against talking too much, but all I can say to that is, it’s done no harm so far. What do you think, Adam?”

“Er…” My heart sank as I faced a sad end to the day, whereby I must admit to having come to the wrong place after all. “Melia, my name isn’t Adam.”

“Of course it isn’t,” she reassured me, re-brightening my prospects so that I was able to swat away the dreary prospect of an embarrassed retreat and a search for somewhere else to stay, “but,” she continued, intensely reasonable, “until you tell me what your name is I’ve got to call you something, haven’t I, and this is my day for calling people Adam as a default option…. no, wait, I do know who you are, actually: you’re Duncan Wemyss. I remember now. Hey, this is good, Oona’s going to love this.” She grabbed me by the arm and pulled me along towards the original row of vans. “Dad always expects me to remember everything he says, but sometimes my concentration wavers.”

I thought: this daft woman can be as scatty as she likes because the possession of huge amounts of money protects her from the consequences; just as the cushion of my reputation, acquired through a long run of rashness and luck, supports me in my selfish laziness – my determination to withdraw from responsibilities and ‘rest on my laurels’ as Cora has so justly put it. So in a way Melia and I are two of a kind.

Marradale House, indeed, fused with my ideal. Not a fixed house but a flowing thing, an adaptable fleet of juggernauts which could ease itself from one place to another to re-form as convenient. That the Reaver-Sunches owned several parks, I didn’t doubt. It came to me in a flash that here was a family who could thus combine the advantages both of nomadism and of settled life. Their ‘house’ moved, split and shape-shifted periodically. Some fixedness was provided by the parks and gardens…

Half-listening to Melia’s prattle, I let her pull me along. I needed allies and it looked as though I might have found one; might there be more, enough to cushion the crash ahead of me, when the time came when I could no longer… could no longer avoid…?

I averted my mind from its iciest fish.

It’s essential, sometimes, to practise the art of not thinking.

No point in worrying over what you can’t bear to contemplate!

In my case, the fish on the slab was the cold staring certainty that there was one last service I ought to perform for Kroth.

“…thanks to you, I’ve escaped a telling-off,” Melia continued. “If you hadn’t turned up I should have had to answer to Her Nibs.”

“Oona’s your little girl?”

“Little in some ways. Here we are, you can see for yourself. You two ought to get on – she’s dying to hear about Down Under. It’s a passion of hers.” Melia lowered her voice at the van’s threshold. “She can be rather quiet…” (quiet by what standard, I wondered) “…but then she suddenly comes out with long words such as ‘incredulity’, a bit much for an eight-year-old. Still, from what the Earth-experts say, Mozart composed his first symphony at that age…”

“Is she that precocious?” I asked in some alarm.

“Just don’t talk down to her.”

I nodded. “That would be a gaffe, would it?”

“Unthinkable,” she agreed, her up-tilted face responding with a grin to my understanding. Then she ushered me into the child’s den.

Mother and daughter, seen together, offered a contrast, for whereas Melia was a petite woman who kept looking up with a kind of eye-popping shrug, a perpetual invitation to agree that matters were getting out of hand, Oona, far shorter still, gazed straight ahead with grave, calm dignity – much the more mature of the two.

“Poppet, this is the famous Duncan Wemyss,” said Melia.

“Thank you, Moppet, you may leave now,” replied Oona.

“You see what I mean?” said Melia to me.

“I see you’re both having me on,” I remarked, and they both laughed.

Melia said, “Well, s’pose I’d better see about supper. Can’t hope to get any staff this evening! Orville should be arriving fairly soon. Call for help, Duncan, when you reach the end of your tether.” She went off, heading, I assumed, for the kitchen van.

Oona, from where she sat with midget legs dangling from a tall chair, fixed her quiet brown eyes on me and said, “Mr Wemyss, I am not as cre-du-lous as people think I am, and I don’t want you to spin stories for me just because I am only a little girl. Tell me the truth about the animals of Hudgung.”

“Your hobby, eh?”

“Yes, when I’m big I’m going to be a zoo-o-lo-gist.”

“Well, all right, I know something about the wildlife Down Under.” And so I rambled on for a while, and she sat and listened, fascinated to hear of the sheep and cattle with legs growing up out of their backs, of the birds likewise evolved to clutch upside-down, and of the others – birds and animals – who kept the ‘normal’ upright structure but who adapted in other ways to the topsy-turvey conditions under Hudgung. She was less keen to hear about humans, including the omong.

“People,” she remarked dismissively, “will do anything.”

“That makes them less interesting than animals?”

“Yes,” she said. “Like in a detective story, if the answer can be anything, who wants to read it? Only if it’s…. tight, only then is it interesting.”

I felt like pinching myself to make sure that this was not a dream, and that I really was talking to an eight-year-old.

I also felt like arguing! “But your house,” I murmured, “is not tight… on the contrary it’s rather flexible…” I was simply probing out of sheer wonderment, to see what she would do with the connection of ideas.

“Do you like my house?” she asked sharply.

“Yes, actually, I do.”

“Yes,” she echoed – and smiled. “It’s got houseyness.” Suddenly she seemed young enough, her proper age.

“That’s a good word. Yes, it has.”

“Miss Seton says there’s no such word, but I told her, ‘there is now’, but she said I was confusing the class.”

“You could confuse ’em even more and call it houseytude.”

She must have decided at that point that I was a friend.

“Follow me – I shall introduce you to Joey.”

She jumped down from her chair and led me to a side-room, hardly bigger than a pantry, which contained a table and a large open-topped box. In the box Joey’s head and limbs were all visible at first as he contentedly munched lettuce leaves, but when Oona lifted him up to perform the introduction the tortoise took one look at me and withdrew into its shell.

“Joey doesn’t like you,” Oona proclaimed.

“Oh well. He knows what to do about it.”

She brightened. “Yes, it’s a good trick, isn’t it.” Then the little witch turned her solemn eyes to me and added, “Bet you’ll wish you could do that, where you’re going.”

“Where… Uh?”

“Daddy says, when you make a speech in the Big House, and people don’t like it, they all make a hissing noise.”

“I’m hungry. When’s supper, I wonder?”

“You’re changing the subject, Duncan.”

“You betcha.”

“Betcha… what does that mean?”

“Means ‘you’re darn tootin’ right’.”

“You know a lot of words, don’t you, Duncan?”

And it’s just as well I do, thought I, mopping my brow.

Just then I heard a dominant male voice two rooms away, forcefully apologizing for lateness, and Melia’s indistinct reply.

Oona, listening, remarked: “Dad’s back.”

“What’s he like?” I whispered.

“Big, bald and boring.”

Meanwhile the forceful voice was replying to Melia, “Glad to hear it, glad to hear it”. Social instinct prodded me to walk towards the voice.

Sir Orville Reaver-Sunch met me in the van’s “lobby”. He was especially huge in those rather cramped quarters, but a fluent courtesy kept him from being intimidating.

“Good to have you with us. What a day!” he declared as we shook hands. “Glad you were able to make your own way here without mishap. Now if you’ll excuse me… I’ll see you in the Hall for dinner in a few minutes. Or even before – if you can give me a hand with the…” I didn’t catch what he said straightaway, but I soon understood. The ‘Hall’ had to be one of the other juggernaut vans. A kind of trunk-sized kitchen unit had to be wheeled over to it, pushed by Sir Orville and me. Melia took charge of it when we’d got it up the ramp. She unpacked it while we sat at table. The meal she had prepared was all there.

Conversation with Sir Orville opened less stressfully than it had with his daughter. His booming chatter spread a veneer of reassuring dullness over my excessively exciting life, as he remarked about how things had changed, and asked me didn’t I think this or that about life in Topland, questions large and vague, too nebulous to get a proper grip on. He also talked about the name, Marradale House. It was, apparently, evolved distantly from a name in an earlier language, Merralafom – “so it should be called Merralafom House, really, but there’s a tendency to make words easier to say.”

Then he got a bit more personal:

“What do you think of our – ahem – unusual stately home?”

Was this his weakness? Could he be sensitive on this point? His eyes had narrowed as he asked the question; did that signify regret at having gone for the mobile van-fleet option, rather than a dignified pile of stone?

If so, I needed to utter a swift, light reply.

“Deceptively spacious.”

“What do you mean by that?” His voice was neutral, trembling on the fence.

Melia intervened:

“He’s being ironic, Orville. Echoing estate-agent speak.”

“Oh.” He raised his eyes momentarily to the ceiling and at once I sensed that all was well. “As my wife will tell you, I have no sense of humour. And my retort to that is that she has no sense, period.”

While he laughed at his own remark, and Melia put her arm round his shoulders while saying warmly, “Score one-all,” Oona piped up with: “Duncan doesn’t believe either of you.”

“Really?” chuckled Orville.

“That’s right, sir,” I said; “they’re both superficial judgements.”

“We’d better retract them, then.”

“No, no,” I averred, “no need, if that’s the way you lubricate the frictions of your married life…”

This time he hooted, grew red-faced and blew into a handkerchief. “You know what you’ve done, young feller, you’ve reassured me that you’ll get along fine in the Big – ” he gasped – “the Big House.”

Quietly I said, “The Big House – that’s Parliament, isn’t it?”

I have noticed, in the vast majority of Krothans for whom Earth is a faded dream, an eagerness to show off their Earth knowledge, dry though it is. Facts which, for me, are personal impressions, backed by sensuous imagery or the recall of live circumstances in which I learned them, are mere data for these Krothans, yet they are keen to reel them off. Sir Orville Reaver-Sunch now exhibited this academic tendency. He lectured me proudly:

“I expect that for you the word ‘Parliament’ conjures up that institution at Westminster, Earth. The House of Commons, primarily. But here, at Savaluk, Topland, Kroth, the Parliament is unicameral. No separate Commons and Lords. So yes, we often just call it (a bit vulgarly) the Big House… and you, Duncan, are going to make a splash there, I don’t doubt.”

“No, Sir Orville,” I replied, “I’m one for the quiet life.”

“You haven’t achieved much of that so far, from what I hear.”

“Just wait, and I’ll convince you.”

They all laughed and I had to join in, reluctantly. I was going to protest and insist some more, telling them of my genuine lack of ambition, but this disclaimer fizzled before I could utter it, smothered by an awareness of how often I had been wrong… so I modified what I was about to add.

“If you do see me in the news,” I told them, “you can bet it will be Sunday supplement stuff.”

“You say that disparagingly,” observed Sir Orville.

“Maybe, but it’s cute, you know… thinking back to the Sunday newspapers in old England: the colour supplements... amazing, how just about every week their covers depicted some famous person I’d never heard of... or didn’t much need to have heard of.”

“Oooooo,” said Melia with a sly look at her husband. “Time for a quick change of subject, I think.”

“Have I dropped a brick?” I asked.

Oona piped up again, “Dad was on the cover of the Sunday Hailer mag couple of weeks ago.”

Responsive smiles rayed all around; thank goodness, I clicked with this family. Having hit the right tone, by dropping the right brick, I could relax for the time being.

*

Three days later I stood, tall hat in hand, amidst a bright crowd, under an ancient hammer-beam roof. Chants of “God Save the King” could be heard from outside. Here inside – almost as day-lit as the outside, so huge were the arched windows – I craned my neck like the rest of us, to glimpse the slow procession up the aisle towards the Throne.

My ceremonial tabard weighed heavily upon me, but in compensation came the happy thought that in this respect I looked as good as my fellow Knights – during the State Opening of Parliament all male MPs were honorary Knights, in green and brocaded gold, while female MPs were all Ladies in robes of deep blue. And to cap the colour scheme came the pleasant old buffer with the crown, hobbling along with his red velvet train that dragged along the smooth floor for yards behind him.

From what I’d heard, John Thaxton had been a semi-retired furniture maker less than a year ago, when the throne had become vacant. Some time prior to this, doubtless because of his volumes of sensitively patriotic poetry, he must have come to the attention of the Lords, and been short-listed. They – in this world not a separate part of Parliament but the electoral college for the making of the Sovereign – had then seen fit to raise him to his new life as His Puissant Majesty John the Twelfth, King of Topland, Sovereign of all Upland and High Protector of Yeyld.

Because his accession had occurred while I was away, the talk about it had mostly died down by the time of my return, but catching a few late echoes I had gained the impression that he had been originally put forward as a stop-gap, compromise candidate, after the electoral college had met in conclave for several inconclusive sessions. Since then, in the opinion of many it was beginning to look as though – as in the case of Pope John XXIII on Earth – the stopgap compromise would go down in history as a remarkably successful choice.

His health was rumoured to be poor, but he had shown that he could be trusted to say the right things and to make it obvious that he meant them; in several broadcasts he’d caught the mood of the nation at the current turning-point in its fortunes, in which the epochal Rise of the Down-Unders had flowed up to Topland… and now, as he plodded past on the final stretch before dais and throne and canopy, I guessed that his most responsible moment was about to occur.

I wished he were more hale and hearty, for his slow creaking movement gave me time to develop concerns about what might go wrong.

I tend to be like this on pompous, formal occasions; though I understand and sympathise with the pomp, and appreciate its role in life, I worry for the participants. Suppose the King were to stumble, or stutter like Britain’s George VI, or go mad like Henry VI or George III?

John XII finally reached those steps, and a couple of chamberlains rushed to either side of him to help him up. Then he reached the throne, turned and sat, and the two helpers bowed and withdrew, one of them having quickly adjusted the royal microphone.

Meanwhile it weighed on me, what might still go wrong. He might say the wrong thing. Everyone makes mistakes. And here the King was not merely a constitutional figurehead; he must be allowed greater freedom in expressing his views, than if he had owed his position to an accident of birth. Hereditary monarchs, in a democratic age, must be ciphers, but if, instead of being hereditary, the system produces secular “popes of patriotism” elected in secret conclave, you then have a half-way house between a president with a popular mandate and a hereditary dummy. John XII did not rule, as a Tudor would have ruled, nor did he provide presidential executive leadership, but he was guardian of heritage, and in charge of those aspects of policy which affected patriotic unity.

Here was room for manoeuvre, decision, choices, errors…

The King gazed at us, and at the TV cameras, and then he spoke.

His first word showed that he, or his culture, rejected the distant royal “we” in favour of the more forceful, individual “I”.

“I welcome you all, Knights and Ladies, and all members of the body politic down to the most uncomprehending babe-in-arms, to the embrace of my words.”

Formulaic, so far. I understood this instinctively. His broadcast words must wing around the realm, preserving its unity, and so he had to begin without surprises.

John XII coughed and went on:

“I particularly welcome our new brethren from the South, from Hudgung. This is the first time in ages beyond memory, that the seats in this Parliament can all be filled. We can rejoice at the privilege of witnessing such a day.

“Now, the best way in which to honour our new M.P.s is to begin the business of the House as usual, to pay them the compliment of full participation.

“My Prime Minister has prepared a programme of legislation for this session. He will shortly utter a summary of this programme. I have seen it, I have checked it through, and he has my trust.”

I surreptitiously glanced at the faces around me, to get a quick estimate of how others had reacted. To me, with my Earth memories and my inevitable comparisons with the British monarchy, this Topland King’s condescension was daring and amazing. ‘Checked it through’, indeed! The Prime Minister, Armand Brett, had just been patted figuratively on the head – in front of the entire nation – with an assurance that his plans were acceptable, that none of them contravened the spirit of Topland. Nobody looked shocked at the King’s presumption – so yes, it was expected. Formulaic again, perhaps. But also it confirmed my suppositions. Here the Sovereign’s role was a real check upon the executive. A sort of Supreme Court of Heritage.

“Trust,” the King continued after a short pause, and a certain shift in his voice hinted that he was about to ‘stick his neck out’ further, sailing further from the strand of set phrases, forth into riskier waves of personal comment, “trust is to be expected between honourable men and women, whether allies or opponents in the political game.” (Game? I did not care for the levity of that term. Embarrassing anxiety gripped me. Suppose the King, on this special occasion, were to dare to make a joke, and it fell flat?) “However,” – this word was pronounced so deeply, it reassured me that no joke was in the immediate offing – “none of us can put absolute trust in Fortune. We sometimes feel that we can sense the tide of events flowing in our favour, but we would be fools to make pronouncements about it. So, my people, you must allow me to strike a note of caution on this bright and auspicious day.”

My pesky mind has a tendency to race ahead and exhaust me with its patter of futures. The King was speaking with great authority. And he wasn’t likely to be making vague points which could be made at any time by anybody. Was he – despite his declaration of trust – trying to instil doubt in the P.M.’s legislative program? I had a hunch that this was not the case. Such an underhand procedure did not seem in character.

What, then, was he up to? I listened on – and his next paragraph gave me a clue.

“…this great movement now known as The Rise, by which the power and the confidence which rayed from the New Star has propelled our brethren in the Southern Hemisphere northwards to meet us and re-unite the world. So, they have done it; they have reached us; they have attained the North Pole. What then? The New Star is invisible from up here, but that does not matter: it has done its work, its vigour has nested within us. What does matter is that The Rise, as such, can go no further, because this is the end of the line; you cannot go northward from here.

“Henceforth, therefore, the movement must transform its own character, or, to put it another way, it must end, its place taken by – what? That is the question which will have to be faced. The energies produced and encouraged by The Rise will not die down; they must be channelled; they will be channelled, deliberately or otherwise. You, my people, will have to decide whether you wish to influence the direction of the channel, or whether you will be borne along in a torrent beyond your control.”

I bowed my head, thinking: so that’s his message: he’s not just doubting his P.M., he suspects that his people also might go wrong.

“…In a way it is like the situation after a great war: ‘demobilisation’ of one sort, followed by the need for ‘mobilisation’ of another sort – meeting new requirements, necessitating different virtues. If it happens, that is. Usually the opportunity is lost. Think about it, my people!”

I looked up once more and saw him frowning around at us all, and then his brow relaxed and he reverted to his formulaic tone.

“Hear now the Prime Minister.”

John XII sat back, while Armand Brett stepped forth from our ranks and approached the lower microphone at the foot of the throne. He bowed to the King and then faced the cameras and us.

To my inexpert ear, all Brett’s speech had the ring of “business as usual”. At any rate, it was on a much more mundane level than the King’s speech – as no doubt was right and proper. For what seemed a long while I listened to the catalogue of proposals which issued from the P.M.’s mouth as he droned on and on about uncontroversial infrastructure improvements.

Then, as I became aware that he had finished, I also detected the tail-end of a general sigh of excitement. Dozens of faces looked to each other, in pairs and groups, with raised eyebrows.

Brett had added something which evidently was supposed to be significant and exciting – and I had missed what it was. Krunk. Oh well, thought I – never mind, considering what life on Kroth was like I’d soon learn more, without the need to try.

*

Indeed, as expected, I only needed to possess open ears and eyes to get the point a few hours later that same day – though I was slower to get it than most.

“They’ve done it,” commented one who plumped at that moment into one of the armchairs behind my back.

I looked around the Members’ Lounge and saw some bright eyes and nods among the relaxing M.P.s.

Oh-oh, thought I, here it comes again, a bout of the old mental asthma, the ineffectual gasp of my starved understanding. Pray it’s not important. “Done what?” I wondered aloud, as I turned back to my own coffee-table.

Sir Orville heard me; he had occupied a chair next to mine. He’d stuck close to me because the thoughtful Government had arranged for the new intake of M.P.s to be mentored by experienced members (‘mothers’) while they ‘learned the ropes’; since I happened to be Sir Orville’s guest, he had reasonably picked me as his duty ‘offspring’.

Now he echoed my question and answered it. “What have they done? Set up the Standards Committee: that’s what they’ve done.”

“Sounds thrilling.” Of course I meant it sarcastically and I was happy thus to mean that it wasn’t thrilling, happy to insist that the world owed me some peace. A scene in which a ‘Standards Committee’ counted as excitement was fine by me.

Yet no sooner were the words out of my mouth than I knew I’d meant “thrilling” for real…

During my career of being kicked around by circumstance, I had developed a hyper-acute sensitivity to significant tones and looks, the sort I had witnessed just now. When recounted in words, it might not sound like much, but I recognized Fate trying its old heavy-breathing act once more, causing an atmospheric eddy which tipped a wing in my gliding mood, but before it could send me into a nose-dive I took counter-measures, bringing positive thoughts to bear: stable, self-satisfied thoughts – immediate memories of a comforting afternoon. After all, the opening session of Parliament had been a flawless triumph for us new M.P.s, especially for Vic. I decided to turn the conversation with Sir Orville in this direction.

“Oh, right,” I said dismissively – to sweep aside the topic of the Standards Committee, whatever that was – and then: “Vic did well, didn’t he?”

“Your uncle is a remarkable man,” agreed my host and mentor. “Knew, instinctively, that the House doesn’t think much of someone who speaks from a lot of notes. He used no notes at all, and spoke without hesitation. I’m quite envious, as a matter of fact.”

“Yeah, no notes – but he doesn’t disdain to use props,” I remarked.

“Ah yes,” agreed Sir Orville. “That went especially well, did it not?”

The main ‘prop’ had been a globe of the world. Next to the Despatch Box, where the P.M. stands to speak, there is a table. Vic had put a globe of Kroth on that table and as he recounted to the spellbound House the route he had taken on the way down South and then back North, he had stuck labels on the globe, to illustrate the additions to our knowledge achieved by the two great voyages.

I meanwhile shall slide no more; shall henceforth refuse to descend any kind of slope without a struggle – says I to myself.

I therefore used the good feelings about Vic’s triumph and the successful afternoon – I used them as a muffler against any naughty significance of the Standards Committee.

“His next hurdle,” predicted Sir Orville, “will be ratification of the Treaty he signed with the Gonomong. If he gets his way on that, and I bet he will, they’ll put him on the S.C., without a doubt.”

“Bully for him,” I shrugged.

“Probably summon you onto it, too, I shouldn’t wonder.”

I let out one cracked laugh. “Waste of their time, that would be.”

My blood had no overt reason to run cold. Standards – laws – special laws – a link I sensed tugging from somewhere deep – never mind, too tenuous to worry about.

So there I sat, smiling with satisfaction, though also quite aware that my personal trinity of cowardice, selfishness and laziness might not be enough to see me all the way through life. I was prepared to give the laid-back approach a good go, to find out for how long I could get away with it. If it got me a long way, I’d settle for that. If, finally, the objections came too thick and fast, I could always back-pedal and say, in effect, all right, all right, if you insist, if you really insist I again take up the wit-pitting business…

Meanwhile the “lazy coward” version of me was determined to stay on top. Or is that too harsh a way of putting it? Wasn’t it the case that I was actually doing what one is supposed to do, namely, appreciating what one has got? Absolutely – my appreciation had developed so firm a grip, that it would take a global threat to pry me loose from the comfy couch of my day-to-day existence. I was determined to keep what I’d recovered at long last, namely, an easy life back on top of the world, maintained by my inner chant of don’ts: don’t wake the baby, don’t rock the boat, don’t break the spell.

*

Later that week I first noted that Vic was not going to have things all his own way in Parliament. It happened on one of the mornings given to the debate on the Treaty. I had settled in my place on one of the backbenches; I was sitting while many others stood, so that the forest of murmurs passed over my head, but I was prepared to give the next major speech a moderate amount of my attention.

The terms Vic had negotiated with the enemy were bound to be accepted, but it pleased the House to take its time and ramble round the issue.

Suddenly a voice from way, way back gave me a jolt.

“Will the right honourable Member for Gannerynch explain how it came to be that my daughter Elaine Swinton was allowed to disappear into the jungle of Udrem during a mission under his command?”

The sight of Mr Swinton here brought the old times abruptly to life. I remembered him as fine through and through, back when we were neighbours in Guthtin village. Professional suit-and-tie smartness on the outside, gently authoritative and kind on the inside, never needing to raise his voice, Elaine’s father had spared time to help a confused neighbour in the aftermath of the Awakening from the Dream of Earth.

But now, finally, he had raised his voice, and I was glad not to be in Vic’s shoes when it happened. Well had the ancients named this site the Trembling Mound: the place where tribesmen came to brave the terrors of public speaking before their assembled brethren. (Nowadays, Press and the media still referred to the Parliament Building as the Trem Emm when alluding to its nerve-testing aspect.)

Vic replied:

“I can assure the right hon. gentleman that Miss Swinton remained of her own free will with Prince Rapannaf. She could not be dissuaded. I personally regretted her decision at the time; however, we have just received a message from the South which may relieve our anxieties and placate the right honourable gentleman.” He paused for effect; the House hummed with interest. “The message says, that the new Sovereign of Udrem intends to make a state visit to Topland some time within the next hundred days. The young lady will accompany him.”

A heightened buzz ran through the House. Vic must have held this tid-bit of news up his sleeve in case it was needed to trump criticism at some point during the debate on the Treaty of Teffenengleng. He could do this because he remained in touch with Rapannaf via the Fleet, rather than via the Topland authorities. Such short-cut diplomacy might raise eyebrows, but the news was undeniably good.

Another member rose to ask about the destruction of the Oracle Root in the battle of Udrem. Had the nature of the Root been confirmed? Had it really been a communication device, a link with the South Polar Slimes?

“The short answer,” Vic replied, “is that the Gonomong themselves, in despair as the fight went against them, destroyed the Root rather than see it fall into our hands. As a matter of fact they insisted that the Treaty credit them with this deed. It was a face-saver for them.”

A neat answer, and the only thing wrong with it was that it was not true. I remembered, for I had been there, in the chamber of the Root: I knew, by unmistakable physical signs, that the Root must have been destroyed many days before the Battle. An awkward memory…. over-ridden by the august atmosphere of Parliament with the grave Members on their velvet-cushioned benches. Let truth be what they agreed. Besides, what did it matter? Who cared about the precise date of the destruction of the Oracle Root?

Down in the darkness of my subconscious mind, the implication which I refused to explore awaited its hour. It mattered vastly – it was the clue to catastrophe – but I did not want to know.

*

The generous salary which flowed into my bank account was supposed to be a parliamentary stipend, but because my level of activity in the House hardly justified it I preferred to view the money as (in effect) a military pension, a recompense for my part in defeating the Gonomong. The highly convenient sums enabled me to rent a house in the City. A few paces from my front door I could hop on a bus which in ten minutes deposited me in Parliament Square. Or, in another direction, I could equally soon reach the Reaver-Sunches’ trailer-park-cum-stately-home, where I remained a frequent visitor. I played chess with Sir Orville, swapped anecdotes with Melia and became an honorary uncle to little Oona as I continued to regale her with stories about the fauna Down Under. Life went on, Fate no doubt coiling as usual for its next cobra-strike, but someone else would have to dodge the venom when that happened, because I, Duncan the Dazed, was used up. Not that I deliberately ignored the news, or withdrew from public life; no, I continued with such duties as my status demanded. But only the minimum. And my attitude ought to have conveyed (to a properly listening world) that I was on holiday from all pressures – the holiday to last until further notice, if you don’t mind, world.

Thus only gradually did I become aware that more ships were arriving from the South, more voyagers from Down Under, following the trail blazed by the First Fleet.

There was no organized Second Fleet as such, but the wave of new arrivals which lapped upon Topland after a couple of months was sometimes loosely referred to by that term. This so-called Second Fleet, then, which consisted not of more giant airships but of a straggling line of more modest craft, transported in comparative safely some of the most important public figures of Birannithep.

The new up-migration made little difference to my life at first, since my tendency was to keep out of people’s way and vegetate on my own, clinging like a vine to the stable props of my existence – my house, my reading, occasional contacts with my friends. I asked little out of life during those months. In fact, the hours of my day which weren’t spent upon my dutiful appearances on the House benches were by and large infused with a happy daze. I benefitted in full from the general popularity of us ‘Risers’. Happy people, in a healthy society, are popular. As well as being admired for our successful adventure, we arrivals from Down Under – both the returned exiles like myself and the adventurous Biris who had never been Up Over before – were regarded with the sort of kindly affection usually reserved for recently-found children or gently tipsy dopes, because our hosts’ compassion was stirred by our recovery from the suffering of an upside-down existence which was surely not meant for man. From our lightened hearts they could perceive that we had never really accepted the dangling life. And when we told them about the thoroughly adapted omong, who were built to dangle, the consensus emerged that only they should have to endure conditions under Hudgung. The Southern Hemisphere ought to be left to them. (I heartily agreed.)

Toplanders soon accepted that we could not tell them much about omong civilization, for we knew little about it ourselves, but they were afire with curiosity about us. They demanded not only to know how we had survived Down Under, but also our whole life stories. Inevitably the broadcast media were going to pick on me, who had fought at Neydio and Udrem. So various demands came for my appearance on TV.

I was able to give them most of what they wanted. At first, when the TV executive approached me to ask my co-operation in a documentary about the war with the Gonomong, I shrank back at the thought that they might want shots of me clambering over the blood-stained boulders which had crushed the enemy at Neydio…. but I was unfairly judging them by the corny artificers of Earth TV. “Don’t worry,” the exec told me, “we don’t go in for stunts of that sort. Besides, all the boulders have been winched up-Slope once more.” My part in making the programme did involve trips to the battle-site but the most dramatic of my duties was merely to revisit in silence the spot where I had stood on the Vallum watching the Gonomong advance. I certainly did not have to pose, or act a part; a discreet cameraman, without my knowing, caught a shot of my wind-blown expression which turned out eloquent enough – the proverbial picture worth a thousand words.

They wanted Vic, of course, far more than they wanted me. He coped with it all while also helping to keep me on an even keel. When, during that day on location, I started to brood, he tugged me back from the brink of molten emotions, as he had done before, with his sardonic quote from the Lay of the Last Minstrel: “The phantom knight, his glory fled / Mourns o’er the field he heaped with dead.” At other times, when he wasn’t around, I was often too dopey to think of anything much to say at all; but that was all right – to the TV people I was then the taciturn hero. When on the other hand I did manage to find my voice, their editorial ingenuity sufficed to make something interesting out of my creaky efforts.

In short, they were competent image-builders. They did a respectable job of presentation, and I had no problems with the arrangement. I even earned my keep, sometimes:

“So – how would you assess The Rise, Duncan?”

This question came on Breakfast Television where I faced the clean-cut Chris Landon, who had a living to earn, a reputation for acuteness to maintain. As a Toplander he might share in the public’s generous euphoria concerning our achievements, but as a TV presenter he had to put himself over as constantly ahead of the game, always ready to prick any bubble of conceit or illusion. And this time I was on my own – Vic was not invited.

And under the searching gaze of Chris Landon I had to say, at last, what I thought of The Rise.

I came up with a forceful phrase.

“Comparable to the Apollo Project in grandeur.”

“So – a great, a fantastic techno-deed. And done for prestige, partly?”

“Prestige needn’t be a silly thing,” I commented.

“Say more. Prestige…”

“Can be an important sign of life… vigour… and, all right, power: a signal that we are too big to mess with.”

Landon’s sidekick, the impossibly decorative Miranda Taine, chipped in at this point.

“You actually saw one of the Slimes, didn’t you, Duncan? At that place – what was it called – Sgombost – ”

“I don’t want to talk about that,” I mumbled, beginning one of my groggy withdrawals.

Cleverly, however, the presenters both stayed silent just then, which impelled me to fill the silence with what was left of my voice:

“Anyhow, shouldn’t shudder, life takes many forms – but they were ultimately responsible for the horrors I witnessed at Neydio.” I shut my mouth in a firm grimace.

They more or less left it at that, thanking me for my appearance on the programme, and as I wandered out of the studio I realized I had said just the right things, moreover without Vic’s presence to guide me. I swung my arms as I walked, rather pleased at his non-involvement. But next time I turned on the TV at my home, to watch myself, there he was – they had spliced him onto the scene as it shifted, so that he eloquently took over. Unprompted, he said: “You know what I think?”

“We never know what you think,” smiled Landon.

“I think of a cloud of midges buzzing,” smiled Vic. “You can picture all the imperfect motivations for The Rise, all the wrong reasons for doing the right thing, as a cloud of midges round our airships at launch, just dimming their glory a little, but not subtracting at all from their greatness as they lift and sidle past the world’s overhanging bulk and zoom into the upper sky…”

I muttered at the set, “Pity that NASA didn’t have you on their staff, Uncle.”

This thought led to the nice idea, that the TV people were all the less likely to bother me again. I’d done reasonably well, but I wasn’t in Vic’s class, and why hire an amateur when you could get a professional persuader?

*

My surprise, when they summoned me before the Standards Committee, was muted by the drone of that inner voice which, whenever I skated on thin ice, reassured me: you can stay easy, it’s not your duty to understand, let life figure itself out.

The Committee seemed to be in continuous session. By all accounts it was a rambling affair, and I sensed this as I waited in the doorway while (by the sound of it) an argument spent itself. I had been told to go in as soon as the Chairman, Sir Jeem Ballonk, had finished with the previous witness. I saw six men and two women around a long table. At the far end of loomed Ballonk, caped like an elderly Batman.

An unfortunate phrase came to my mind. Such-and-such a Committee, I had heard, had “teeth” – meaning authority, of course; but unhappily at this moment I thought of real teeth, and from that point on I was never happy at the sight of a group of solemn people seated around a table. In my imagination they tended to turn into white teeth around a gaping oval mouth.

Sir Jeem was umpiring a dispute between Vic and a younger, chubby, vociferous fellow who just then boomed out: “You’re not a physicist, Chandler, you’re just a science correspondent. You write for popular magazines… like I do.”

Vic riposted: “Heard all those stories about famous mathematicians counting their change wrong? Or professional astronomers who never put eye to eyepiece? I’d say it’s the lesser souls like you and me who have time for the essential – Ah, but wait, here’s my fellow Earth-mind, Duncan Wemyss, hovering in the doorway! Can we call him in now, Sir Jeem?”

Ballonk summoned me forward. “Mr Wemyss, sit down and help us out. We’re feeling humiliated.”

“Why’s that, sir?” (Humiliated? Aggravated, more like.)

“Memory loss,” he replied. “The Earth-dream ended more than a year ago. Since then, our recollections of it have faded to such an extent that we’re becoming unsure of the names of the most basic formulae, natural laws and physical constants of that dream-domain. At the time when the world woke up from it, we were all too excited to write down its details, and the details thereafter became fuzzed… till now The Rise has at last inspired us to save as much of them as we can. But if we’re to harmonise records with our Biri friends, we must first agree amongst ourselves.”

“I’ll help if I can, but…”

“Mr Chandler insists that the name for that gas-volume-varying-inversely-with-pressure rule is… uh, let me put it another way: what do you think it is? Boyle’s Law or Doyle’s Law?”

“Boyle’s Law, I think.”

Vic punched the table. “Right! Right!”

“Thank you, Mr Wemyss,” said Ballonk, “that’s just what we need. We needn’t take up more of your time today, but please feel free to attend this and future meetings as you may wish.”

“Thank you sir; I’ll go now, if I may.” My inner commentator droned, what a petty meeting, teeth or no teeth, and I smiled as I went out the door. This session of the Standards Committee had devoted itself to harmonisation of names for laws. Others maybe would deal with standardising weights and measures. Then perhaps there’d be the establishment of a common currency. Everyday foundation blocks of political unification between North and South – and of course Vic would be a leading light in the whole business, though for him it must be a bit of a come-down from Facilitating The Rise…

At that stage I still had no conscious inkling of the scope of his plans.

*

It ought to have

been obvious, knowing him, that there must be more to it all than was

immediately apparent. But at the time, Committee-work seemed to offer

sufficient scope even for an ego the size of his, because he was so famous that

anything he did was newsworthy. He

aroused the admiration both of supporters and of those who wanted to make a

name for themselves by scoring points

against him – a most flattering kind of opposition. To win a round against Vic

Chandler was a popular aim for any ambitious politician or media person. I

viewed this as a welcome development. It was likely (so I assumed) to keep him

within manageable bounds, and thus make life easier for me.

A tall, silky

figure rose from a chair a short way down the corridor as I walked out of the

Committee Room. I recognized her, the glitzy Miranda Taine of Breakfast TV, but

did not connect her move with my emergence from the room, so I expected, as I

nodded politely, that she would pass me and go her separate way; but instead,

she stopped me.

She laid a

familiar hand on my arm.

“Duncan, would you

do me a favour?”

“I… maybe. What…?”

“For starters,

listen to an idea – if you’re free.”

“I can’t honestly

claim to be busy at this moment,” I admitted, blissfully unaware that Fate had

its foot on the accelerator; I expected her to say, let’s go into such-and-such

a waiting-room or unoccupied office where she’d explain her proposition, but instead

she uttered an unexpected word:

“Barlodd.”

“Eh?”

“The village of

that name.”

“I know of it…

but…”

“Come on,” she

said cheerfully, and conducted me towards the exit. “It’s where your Biri

Archbishop is lurking right now.”

I was swept along,

with ideas that flapped in a tightening arc, like a curved row of manta rays

which had limited room to ripple…

“Did my Uncle Vic

put you up to this?” I asked.

Miranda threw back

her head with a trill of laughter. By this time we had caught the Hockston

Light Railway. In three little stops it would get us to Barlodd. Most of the

seats faced the front, but Miranda went straight for the long side-seat which

you were supposed to reserve for disabled people or mums with pushchairs. There

we sat side by side, and she swayed as she laughed at my words. Several other

passengers must have recognized her famous TV face judging from the way they

elbowed each other to take note.

“It’s taken you a

long time to start asking questions, Duncan!”

“Well, did he put you up to it?”

“To what?”

“Whatever you’re

getting me into.”

“Actually, no, not

on this occasion. We are acting with

his approval, yes, but he’s running out of hours in the day…”

“Can’t pull all

the strings himself, so you’re helping him out,” I nodded. “I see.”

Miranda, looking

amused, said: “But don’t you want to know a bit more about it before we get

there?”

“Miss Taine,” I

declared, “the last thing I want to do, in situations like this, is ask for

details and explanations – because what do they bring me? What d’you s’pose

happens when I get them? Obligations, involvements – that’s what! A duty to

react.”

“You’re going to

have to react anyway.”

“Yes, but not

beforehand! I can’t understand those politicians who when interrogated want

‘advance notice of the question’. Don’t they realize that knowing beforehand

simply increases the amount of work they have to do to prepare? Whereas if

they’d only leave it all for the moment of surprise, they could then

justifiably say, sorry, can’t be expected to answer that one off the top of my

head…”

“But, but, hang on

a moment,” interrupted Miranda, almost bubbly with mirth, “that just postpones

the work, doesn’t it? Because you’re then expected to figure out your answer

for next time…”

“Not after it’s

happened so often, that the public learns a new protocol for interviews,” I

said, warming to my theme. “When they realize that the questioner ought to do

as much work in framing his question, as the answerer is supposed to do in

answering it...”

“Ha – you’ve got a

hope,” she said.

I quite liked her

for that. She was, in a way, agreeing. Nevertheless, what could the likes of me

have to do with the likes of Miranda Taine? My mind backed into its shell.

But through the

open end of the shell came a jab of beauty, from outside the big window on the

opposite side of the bus. No doubt to Miranda the passing view was merely a

pleasant flow of landscape, but to my infantile state of mind the procession of

trees and hedges and creamy stone houses and side-lanes and village greens and

lawns suddenly began to use their visibility to yell, “love us!” “love us!” My mind edgily replied, “I do love you, you gentle cultured landscape,

so why do you ask me that?” It was all uncomfortably reminiscent of a

despairing good-bye, and I groused to myself: I suppose I shall have to give

in to whatever demands will be made at the end of this line. I can save myself

bother by yielding straight away...

By the time I had

straightened out my wits, we were at Barlodd, entering the lobby of the village

hall, and I already heard voices. Well, if one scene wants to flow into another

so soon, and if the flow gets too dense and rapid, consider it as payback,

Dunc, for your months of lazy neglect. Mouth set in a grimmer line, I marched

towards the voices.

Miranda put her

hand on my arm again and stopped me. “Let’s listen a moment,” she said. “Let’s

not interrupt. It’s the Archbishop speaking.”

It can’t be Ray

Ballater of Gannerynch, I know his voice,

this one is younger. Some other Archbishop, then.

The voice boomed

scornfully, “What’s he gonna say? Is he, like Edward VIII, gonna say,

‘Something must be done’, and then not do anything? Rapannaf will have to face

the issue some time.” There was a pause.

Miranda murmured

to me, “Now let’s go in.”

*

She pushed the

wooden door. For the umpteenth time, I impatiently thought, I am entering a

room with a long table and a lot of important folk seated around it in debate –

in other words life is up to its old tricks. Again it cries “wolf!” in solemn

style, with its Committees of wolfish teeth, and I’m tempted to wrinkle my nose

and dismiss the crisis which hangs in the air. It’s not just that I’m lazy,

it’s that a fellow wants a bed that won’t collapse when he lies upon it, and

similarly I want a homeland and a society robust enough not to need rescuing

again and again. Something in other words that runs smoothly and long-lastingly

and safely of its own accord – that’s what I want, for I’m fed up with the

neediness of the world.

From news photos I

recognized John Draschen, Archbishop of Savaluk, and Ray Ballater, Archbishop

of Gannerynch.

Ballater looked

old, but Draschen, with his slim build and white garb, could have been a

professional cricketer, tanned and fit. And that tan could not have been

obtained under the sunless sky of Topland; it could only have been acquired on

frequent visitations to lower Upland. Here, then, was a godly go-getter, a

restless spirit. But, more than that, his remark about Edward VIII strongly

suggested to me that he was in possession of fully educated memories of his

Earthly life. In other words not only was he an oneiro, like myself, but a

superior rival to my own Earth-experience. I was fascinated, as I approached

the table, but at the same time I was alarmed at the thought that Miranda and I

were interrupting a high-powered conference… I said inanely: “Sorry, looks like

we’re late…”

Draschen drawled,

“You can’t be late. Or early, for that matter! This confab is as endless and as

beginning-less as an Eastern Orthodox service, where you just walk in and out

as you please.”

This reassured me,

but the way both Archbishops greeted Miranda was beyond funny – in fact not

funny at all:

“Ah, the TV lady.”

“Sit down, Miranda, and muck in with your Breakfast Opinions.”

She grabbed a

chair while I hung back. “Happy to oblige.”

Casual, this

‘tightening of the arc’, the way she fitted in. Her show-biz glamour ought to have been out of place but

wasn’t. TV bimbo at ecclesiastical conference: could only mean: less and less

space between themes on the shrinking circle of experience… less and less

separateness… varied items must rub

together more and more… galaxies converging in a closed cosmos for the Big

Crunch...

“Duncan Wemyss,”

said Draschen, his voice bringing me out of my swaying visions, “come, do take

a seat.”

Miranda added,

“Don’t look so solemn, you’re making the clergy nervous.”

I interrupted the

laughter that ensued:

“I see – mustn’t

break the Law of Solemnity.” I pulled out a chair, plonked into it and leaned

forward to rest my elbows on the table. “Not joking. Something always happens

when people sit around like this. Whether they think they’ve decided anything or not. The, er, the Magic of

Solemn, starts to work. Has sharp strong teeth.”

“Give it a boring

name, then,” smiled Draschen. “Then the magic will die.”

Well, thought I,

pressured by his bright eye and his half smile, he’s welcome to his greater

intelligence, but, contrariwise, with a wistful pang: would it not be wonderful

to know where I was being carted? At

least, to know whether it was a rubbish tip… or worse. Perhaps the crowdedness,

the bunching, the closeness to the end, was more intense than I had dreamed. And

that meant –

Shut up you fool, will you shut off this damned stream

of consciousness for once, and try to listen to actual events.

I straightened in

my chair. Minutes had passed and the committee had proceeded to finish off one

item on the agenda. They’d been talking about reports from Udrem; about Prince

Rapannaf (his full title now Prince Regent Rapannaf) and his problems with

putting an end to slavery.

It was a moral

dilemma: what to do with slaves who didn’t want to end their condition? For

apparently many of Udrem’s slaves were so far gone that they didn’t want

freedom; couldn’t even imagine what it was. Should they be forced? Traumatised

for the sake of an abstraction they couldn’t comprehend? Back and forth flowed

the argument, ding, dong, until Draschen brought it to an end:

“The problem,” he

said, “would not exist on Earth.”

A spurt of saliva

into my mouth was all that stopped me from grumbling, inanely, “That’s let the

cat out of the bag.” As it was, I preserved my silence, but it could not be for

long.

The other

Archbishop piped up next.

Paler than

Draschen despite being the southerner, Ray Ballater was also shorter, almost

shrivelled, with the lax curled lip of a humorous old man. Lolling back he eyed

me and said, “Time to bring Mr Wemyss into the conversation. It would be a

waste to leave him out.”

I heard myself

ask, “Who says so? The man who’s too busy to be here?”

Ballater nodded,

“In any case the Facilitator preferred you

to be here. He told me: ‘Duncan’s the Holy Joe out of us two; get him to sort

it.’”

“Oh, great,” I

said bitterly. “If your religion is insincere you’re a hypocrite and if it’s

sincere you’re a Holy Joe; you can’t win.”

“Come now, you

know and I know that we don’t need to win.”

I could say nothing to that. He went on: “Reality does the winning for us. And

talking of reality…”

Draschen

interrupted, “Yes, Duncan, tell us your views

on the so-called Ground State and its relationship with the Excited State….”

My eyes popped and

I wanted to say, hey, shush, you’re saying it out loud! But these were special

people and the times were special times (getting

specialler by the minute, as my shying brain protested), so I played along:

“What about it? The Ground State – us, reality, our world – what’s the point of

having views on it – it just is.”

“Ha – that’s odd,

coming from you. Or from me, if I were to say it.”

Because he, like

me, properly remembered Earth.

I bowed my head

and squeezed my eyes shut, to no avail.

“Earth,” Draschen

went on, “had outlawed slavery. It still occurred here and there, but nowhere

was it legal…”

“Earth,” retorted

Ballater, “was a moral cesspit, as you well know.”

Draschen retorted,

“But it had dealt with slavery – ”

“All right,” conceded Ballater, “it had

abolished slavery, but personally I’d rather be a slave than drown in my own

puke – ”

I cried “Stop all

this hammer-and-tongs stuff: you wanted me to come in on this, so listen! You

keep saying, Earth, Earth, as though there was a plan afoot to bring it back. Is

this so?”

Ballater was

looking hard at Draschen.

Draschen said,

“Call it a plan, call it a process, both science and religion are sharpening

that way… Excitement will bring Earth, I’ll wager it. We’ll emerge at some point from the vague stuff we’ve

got now, into a world with its science more exact, its religion historical –

namely, Earth.”

“When?” said I.

Draschen shrugged.

“Eventually. Not any time soon, I don’t suppose.”

That was a kind of

turning point when I perceived his double-think. He was like so many others,

excitedly playing with fire, yet not really believing that it would burn anyone

any time soon.

The other

Archbishop turned his strained face to me. “Whom do you support, Duncan? Where’s

the real Christianity? Remember, Earth doesn’t exist all the time; Kroth does –

”

“Just ask him the

question, Ray; ease up on the bias,” rebuked Draschen.

I wanted to say,

yes, Kroth is the ground state and therefore Kroth is the more real. The

trouble was, I couldn’t say it.

By way of apology

I mumbled to Ballater, “I’m not into floor-bias.”

It was true, I

never had been into the habit of giving more weight to origins than to

destinations. What counts is where you’re headed, not where you come from. I

looked to the upward pull… but I didn’t want to say so, for I loved the world

of Kroth, and craved the continuance of my life and home in Topland. I was

young, my life stretched before me and I didn’t want it be-slimed by the gross

adult fate that lay in ambush. But what can you do? The truth is the truth.

“Earth, when it

comes, will be the heavier dream,” I admitted. “Let’s hope it doesn’t come

soon. We’ll regret it when it does. We,” I continued, allowing myself to get

worked up, “or rather I should say YOU, are mad as hatters, I’m sorry to say,

because all the people who think like you, and even those who think better,

know where we’re heading, talk about it, warn about it and yet at the same time

don’t REALLY believe it! Uncanny,

this double-think of yours. You’re just sleep-walking towards Earth.”

They were posh

people, they couldn’t shout at me like I had just shouted at them.

Ballater said to

Draschen: “It will be a trade-off, I suppose. The truths of our Faith will

become more literal, but by that very fact they will rouse more opposition; the

focus gets sharper both ways, because both good and evil get stronger, more

extreme. That’s how the so-called Dream will go.”

That’s right,

ignore me, I thought; ignore my point, my accusation.

Draschen replied

to Ballater: “You admit, then, that the ‘cesspit’ will have its points.”

The other

shrugged, “Anyhow, we can hope not to drown in it. God (we can assume) knows

what He is doing, tempering the wind – or rather, sanitising the cesspit – to

the shorn lamb....”

And so they went

on working out their “angle” on the topic of Earth, paying no attention to me. I

meanwhile zoomed out in my vision and saw the situation of the real world, more

clearly than ever before. I saw people in three groups. For the majority of

Krothans, whose terrestrial memories had faded into mere reference-data, Earth

by now was a vast blank slate onto which their imaginations mostly scribbled

whatever they wished. For the minority who did retain personal Earth memory, it

was an exciting source of comparisons, aspirations, hopes and fears adding

spice to life here on Kroth. Lastly there was the third group, viewing Earth

neither as legend nor as ‘topic’ but as an imminent threat which demanded

decision: should we keep on course towards it or swerve while there is yet

time? The problem was the small size of this third group, consisting, as far as

I knew, only of me.

Offensively, the

archbishops had brushed aside what I had tried to tell them. But then, come to

think of it, I was being paid back in my own coin, for in my outburst I had

similarly snubbed what they had been saying. Not that my dissent could make all

that much of an impression. A tooth that’s out of alignment can’t bite as hard

as the others.

Miranda, suddenly

jolting my attention, said to them: “Now that you’ve sorted all that out, can I

ask where you are as regards the Balloon TV Project?”

The prelates

turned their gaze to her, doubtless glad of a change.

“I was in Zanep

the other day,” Miranda went on, naming a picturesque old grey stone town close

to the Mulkut Hills. “They’re agog to know whether funds are likely to be

available… and the answer is more likely to be yes, the more support there is

for the legislation…”

The Balloon TV

Project was just another infrastructure thing, intended to improve TV

transmissions by means of apparatus floated high in the air on balloons linked

to the ground by ultra-light cables. Aesthetic objections had been countered by

a promise that the entire apparatus, cables and balloons, would be painted sky

blue to minimise their visual impact. Cost-objections, though, had been harder

to meet… because of the need for multiple

redundancy, the vast expense of back-up systems necessary in a universe where

the laws of nature operate unreliably, as though they can’t speak without

stutters and coughs – I saw the relevance now.

Draschen smiled

and spoke in his witty fashion: “So the construction workers at Zanep are

anxious for Nature to obey the Commandments?”

Ballater snorted,

“So we can all get richer.”

Miranda remarked,

“Well, isn’t there something about God’s blessing on the just man; barns full,

fields of corn, fruitful orchards et cetera; so also, there ought to be a

blessing upon law-abiding Nature…”

“You can announce,

on your show,” said Draschen, “that the Standards Committee have our support.”

And now the lesser

voices chipped in, other men and women round the table, the minor clergy who

had kept silent so far in the meeting while the two ecclesiastical giants

debated. Miranda’s intervention had encouraged them all. I gradually slumped as

I listened to the many expressions of their approval. Some minutes later, I

bestirred myself. Exchanging a wave with Miranda and a nod with the bishops, I

quietly left the room.

*

The after-image of

the debate at Barlodd lingered like a creamy smear across my inner vision when

I next attended a group discussion, as though all such activities are episodes

in one continuous game. And in truth I did have the strange feeling that my

‘Law of Solemnity’ gave every debate a common character, they were all

incantations to summon a future I did not want. I shook my head and tried to

expunge this bizarre notion as I sat in Parliament a week later, while Ohm’s

Law was grinding through its second reading.

An industrialist,

Steve Maragoom, the member for Churbton, had risen in an attempt to hurry

matters.

“Mr Speaker, since

Newton’s Laws passed on Saturday with hardly any opposition we have already

sensed a definite improvement in the performance of all our factories – there

is no question but that the united focus of the public mind has an effect upon

the efficiency and the consistency of Nature’s operations. This next measure

should likewise be of firm benefit to the economy of Topland and I urge the

House that it should pass without further delay. It is long overdue.”

Rumbles of “Hear, hear” and “uoorrraaayyuurrr” greeted this speech.

Vic rose. The

chamber swiftly became hushed.

“Mr Speaker, I

understand the honourable Member’s impatience. To some extent I share it. But

the ‘united focus of the public mind’, to which he alludes, needs to be applied

with care. I therefore suggest a modifying clause to the measure we are

debating. We know the name – Ohm’s Law – and the subject matter – electrical

resistance. I suggest we limit its application, for I have a strong suspicion

that it is not one of the absolute laws. My recommendation is that it should

only apply to a certain list of ‘ohmic conductors’ and to those only in a range

of moderate temperatures…”

I got up,

unnoticed, and stumbled out of the chamber. Why

stay to listen to the inevitable? He knows what he’s about. The clauses he wants will be added in

Committee even if they’re not tacked on here and now. The rest of the House

trusts him, rightly, to remember more than most of us can about rule-bound

physics. He’s going to build a structure that works.

Unless – unless

even his memory was not enough. That

was my only hope. Hope? Why should I put it in that biased way? Why assume that

it was desirable that he should fail? I wasn’t sure why, but I knew what I wanted: a life here, on top of the

world I had grown to love. A world in which the heroes of my boyhood would have

felt at home. All of which (I felt in my bones) was under threat from these

determined legislators.

I leaned against a

column in the portico of the House and gazed into the sky, as if to plead with

someone up there.

I saw a couple of

bright moving spots up in the blue, which further reminded me of the confidence

of Toplanders. Since the Rise had beaten the jinx which previously inhibited

aviation, flying-clubs were proliferating…

“A fine day,

surr,” remarked the policeman on duty.

I replied, “It

certainly is,” and to myself I added the thought, if I am to enjoy many more fine days here, I could wish that one of

those planes might lose control and crash down onto the Parliament building… but

no, that idea was as useless as it was nasty. Even if some Krothan equivalent

of Guy Fawkes could blow the place up, what would be the use? The people would

simply elect another lot and we’d be back on track to the loss I dreaded…

I haunted the

House of Parliament in the days that followed, though unable to bring myself to

speak in debates. I was oppressed by a sense of being dragged towards doom by a

trend too powerful for me to protest and at the same time too hypnotically

vague for a practical response. The successful compromise over Ohm’s Law was

followed by negotiations over other second-level laws, so detailed that I

sometimes thought, hooray, they’ll never get through this lot; they’ll have

forgotten all the details long before they reach the end of the list. But then

more dreadfully and more wisely I thought: I bet they don’t need to pass all the laws, just enough of them to

create a momentum for coalescence… at which point, whoosh, we’ll congeal into

the rule of Law in the universe of Earth.

I was never sure about all this. Some encouraging

signs began to appear, of increased opposition in the House. One chap – a

diminutive fellow whose name I never learned, the Member for Drayzun – began to

sneer at the pretensions of Science. “Science of the Gaps!” he mocked. “Stuff

happens, and so reasons must be given!”

He was no match

for Vic, unfortunately.

“Stuff happens,

indeed,” said my uncle in the deep and knowing voice he used to quell those who

gave him trouble. “You, my right honourable friend, just wish to leave it as it

is, rather than build it up into something coherent; but we have recently shown

that the build-up is the bedrock,

reality is firmer the higher you build – until one unimaginable day, many

universes from now, when the transcendent and the analytical shall no doubt

fuse into one overarching truth. Then we’ll have reached the top and the depths

at the same time. Religion will have become science, and science religion. Meanwhile

let’s get on with passing those laws we know of.”

He paused, holding

the attention of the House as it were in the palm of his hand, and then his

head turned and I thought his glance rested on me.

“Much has been

whispered, recently,” he went on, “about the danger or the promise of restoring

Earth, as a by-product of the laws we are passing. True, the momentum we have

created may have unforeseen consequences. Kroth, however, cannot be lost,

whatever happens. The ground state is always real, and needs no help in being

real; I ask the House to remember that! Remember: Earth, if it comes alive

again, is a mere superstructure – and an intermittent one.”

But a minute ago you’d just made it clear that the

superstructure, or the ‘build-up’ as you called it, is where the weight

lies. Come on, Uncle, come clean –

The work rolled

on. Under pressure of business the Standards Committee swelled till it split in

two. Henceforth, it was the Details Committee for the “particulars” and the

Cosmic Committee for the “ultimates”. Det-Com set to work on Boyle’s Law,

Kirchoff’s Law, stuff of that sort. Cos-Com with less success began to tackle

what was left in people’s minds of Einstein’s ideas and of quantum mechanics. If

the dreaded resurgence of Earth depended on Cos-Com finishing its job

successfully, I knew I could sleep easy. But for a while now I had suspected

that the work need not be complete. Indeed the rumour began to hum that some

sort of higher reality might crystallize at any time out of the work of

Det-Com, whenever a saturation point was reached.

Might. Or might not. I

had my hopes.

I prayed that

forgetfulness would win the race against excitement. The memory of the Dream of

Earth had been fading ever since the Awakening from it, which was more than a

year ago now, and with every day that passed, the contents of the dream receded

further into the mists of time. If we could reach the day when too much had been forgotten, the

legislators would not be able to re-trigger that state.

I also prayed that

I was not guilty of having hastened, even by a single minute, the current

outburst of law-making. Uneasily, though, I remembered what I had said to the

archbishops at Barlodd. It was shortly after I’d opened my big mouth there,

that the House’s physics-frenzy had begun.

*

Vic continued to

perform. He kept people impressed and guessing, while avoiding cliché as he

surmounted one wave of criticism after another. However, others besides myself

grew doubtful about where we were being led, and there were sharp words and

frayed tempers in Parliament. On the other hand, in a way which I hadn’t

expected (but ought to have foreseen), some Members became paradoxically keener

on the re-establishment of Earth, the more they disliked the methods by which

it was being made possible. This is because the more upset they became at the

proofs that they were living in a will-powered universe, the more attractive

became the idea of changing it for one supposedly more stable. Earth would give

them an environment in which natural laws were not enactable by men.

I, too, sometimes wavered, though for different reasons. I caught myself

thinking, “If the Dream of Earth did return, I might meet Elaine Dering again.”

The saying, “the grass is always greener”, becomes in my case “the girl is

always greener”, green for hope that this time it would go right. Pitiful. Sure,

once upon a time, at school, on Earth, I had been in love with a lass called

Elaine Dering, but then came Kroth and the other Elaine and Cora and Heather

and even Gemma Rosten, all of whom had gone their own way, and if Elaine D.

ever hove into sight, the pattern would be just the same. Failure of

reciprocity. No synchronous click of her feelings with mine. Therefore better

leave her shut away, the dream-girl in the golden box of idealistic memory. And

so I did not believe there could be any adequate compensation for losing Kroth.

So my wavering course returned - to opposition.

A silent,

ineffectual opposition to what Vic was doing.

I left the

attempts at point-scoring to others, because I wasn’t up to it. On one occasion

a little slip of a girl named Alla Foonogost, a Biri MP mentored by Mr Swinton,

had the courage to stand up and force the House to consider in practical terms

what we would find if Earth did resume. “Surely we need to give a thought, Mr

Speaker, as to where we will stand, geographically and chronologically, on the

restored Earth.”

Vic shot to his

feet: “Mr Speaker, if I may, I would point out that our subconscious minds are

surely capable of filling in the gap of a little more than a year of Earth