land rush, king rush, moon rush:

a ticking genre-clock

for

the 1930 lunar epic

by r h romans

The redoubtable Dorothy Brewster begins her tale:

Ever since I was just a little girl, the moon has been the most interesting and fascinating object in my life. Among my earliest memories as a four-year-old, is that of the time I asked Aunt Mary (who was the only mother I ever knew) to get it for me, and she answered it was so high she could not reach it. I could not understand this; for she had never before failed to get anything I wanted. When I cried for the moon, she thought it was very funny and laughed at me.

Then, in my childish mind, an ambition was born...

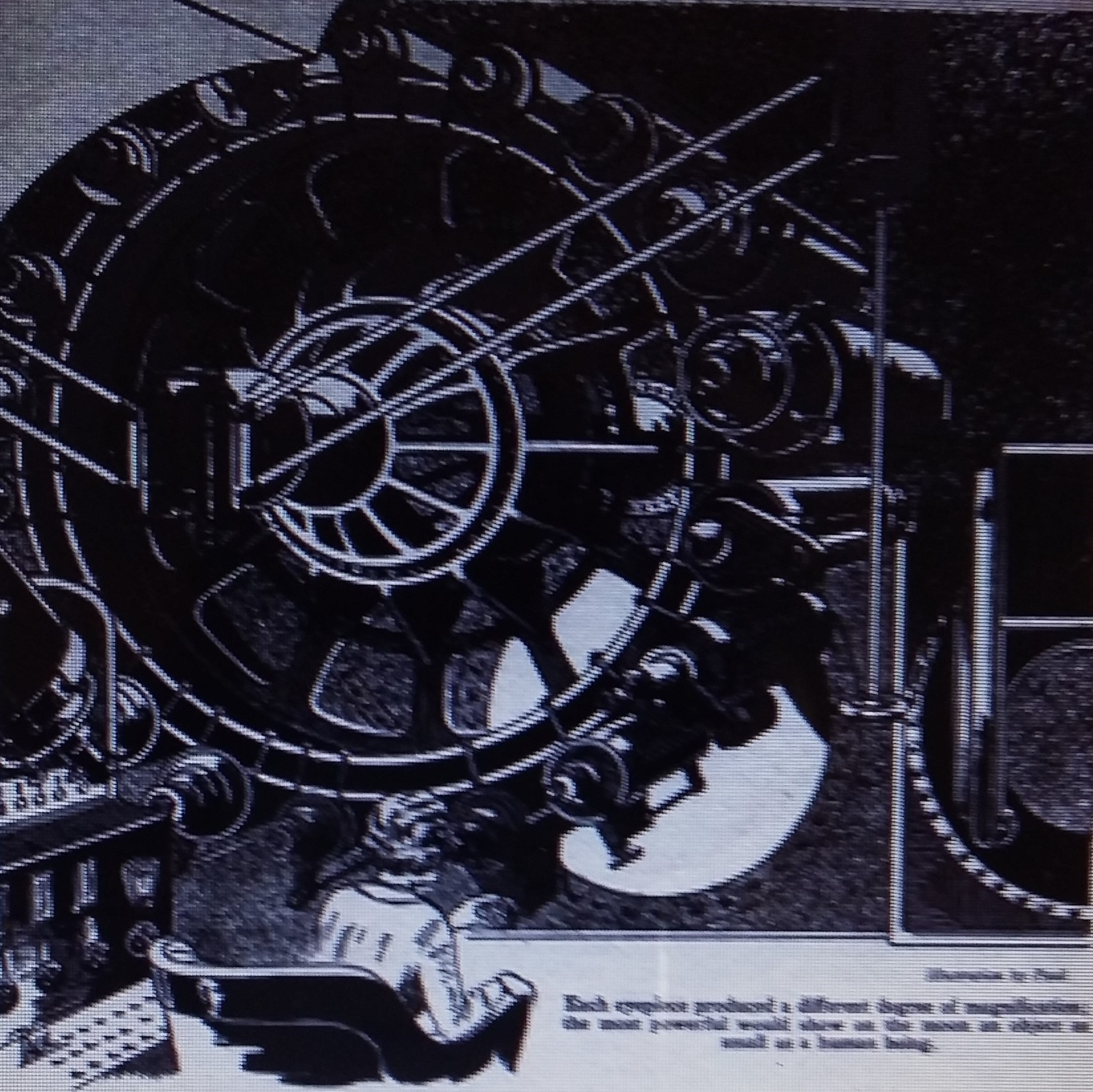

"Eye of the world"

At eighteen Dorothy learns from her father that he is planning a giant telescope which will allow one to see objects "as small as a man" on the lunar surface.

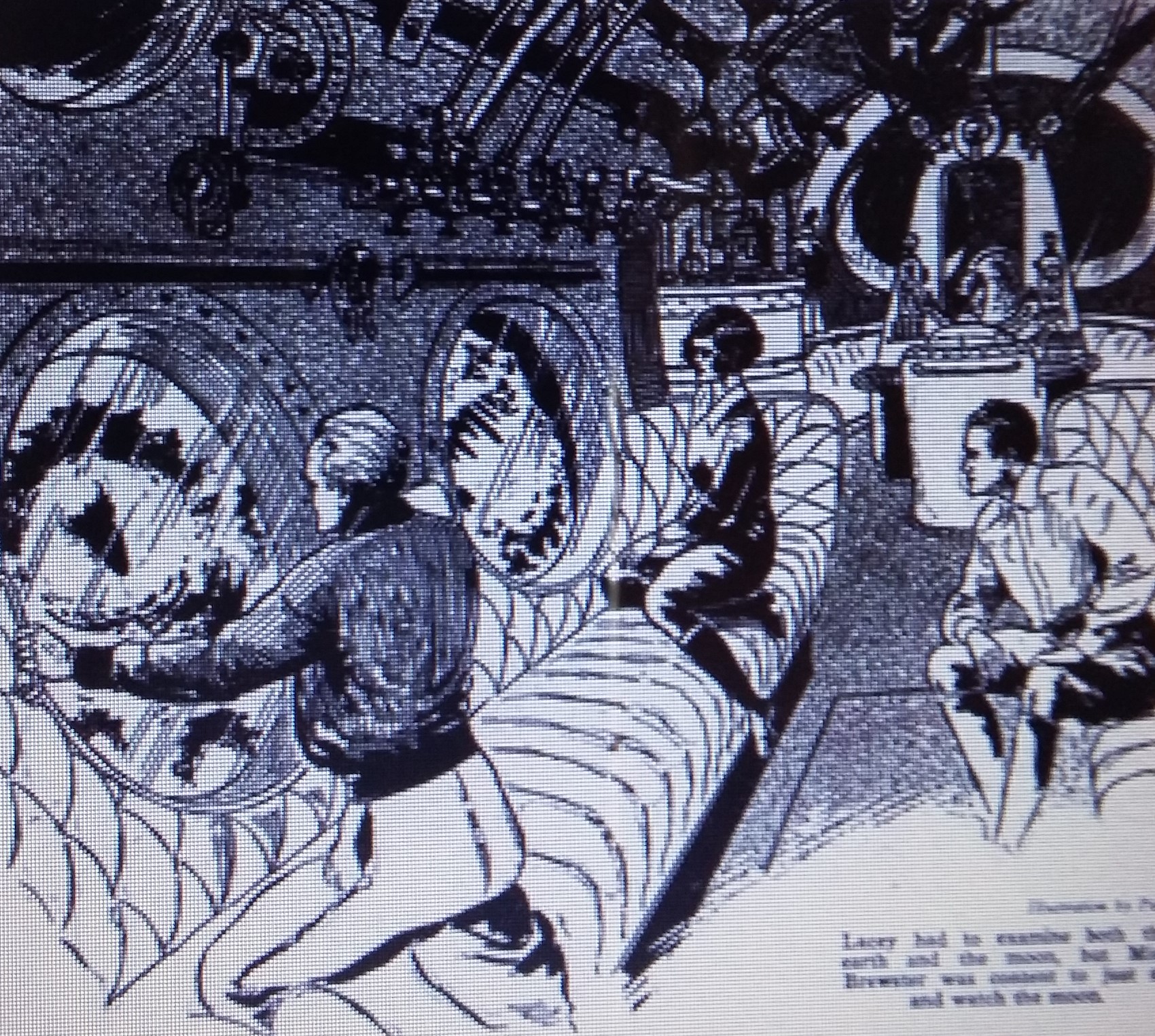

Dorothy at one of the eyepieces of her father's giant 'scope

Dorothy at one of the eyepieces of her father's giant 'scope...The next four years of my life were spent in college, where I did my best to break down the old tradition of masculine superiority in scientific subjects. I mastered the subjects my father had prescribed for me and made an enviable record for myself as a student. The moon still remained the object of my devotions; the big telescope in the university observatory opened up many of her mysteries to me. But, in spite of my knowledge that the moon was a dead world, floating in a perfect vacuum, when I saw her I felt a renewal of my ambition to reach her and carve my name on one of her highest cliffs...

Stid: And, oh brother, do we get told about her father's giant telescope! Such heavy wodges of detail... I wouldn't mind if the author, having told us that twelve years and twenty million dollars were spent on the "eye of the world", left it more or less at that.

Harlei: I was quite interested in the telescope. Mildly, anyhow.

Zendexor: Same here, but Stid's right, the story does drag in places. However, that's not a problem to the primed reader. If you know what sort of stuff to expect from the pulp-mag milieu, you can twiddle your inner browser between "focused" and "skim". And my aim here is, precisely, to "prime" readers so that they may enjoy what there is to enjoy - which, here, is plenty.

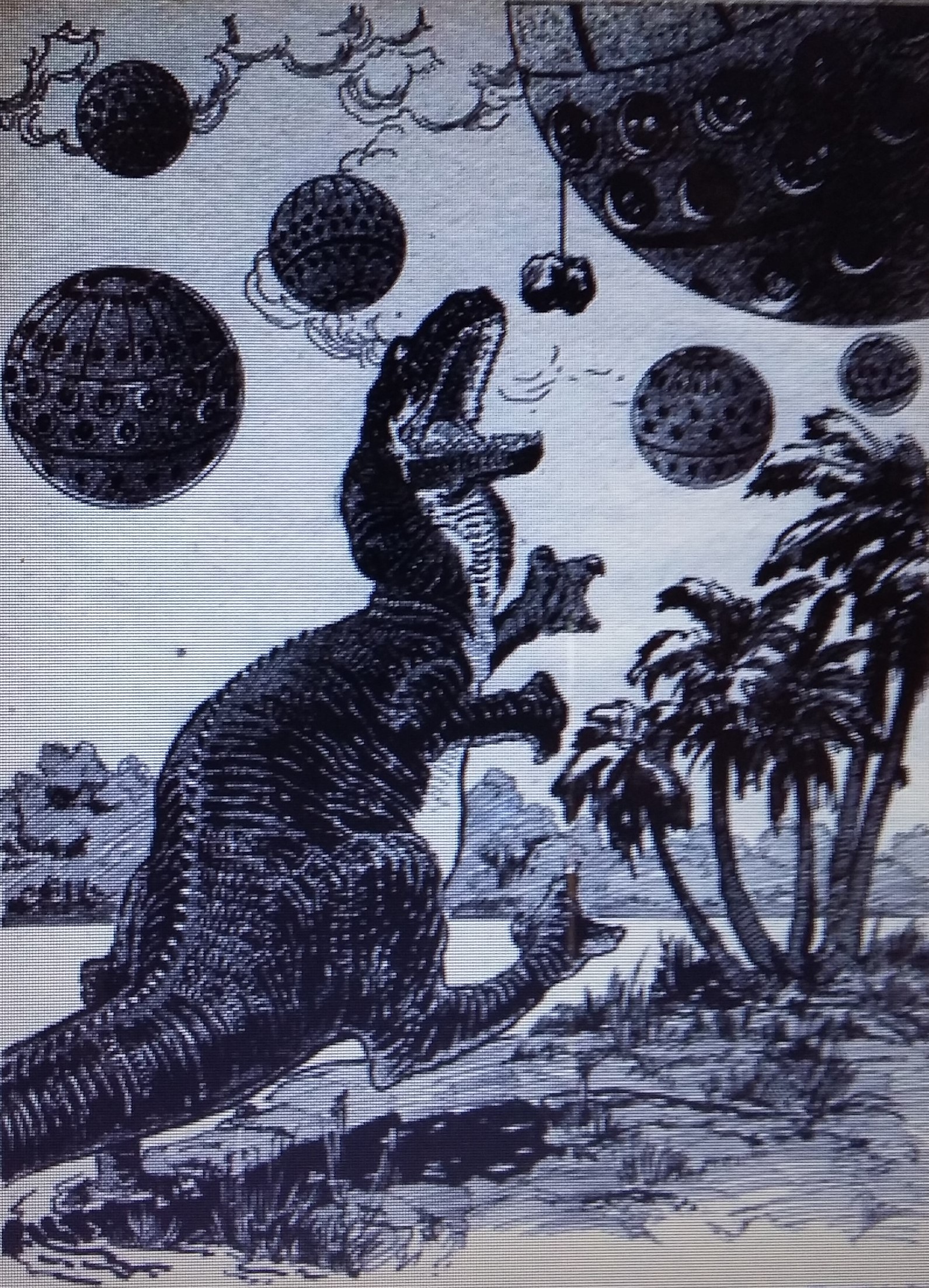

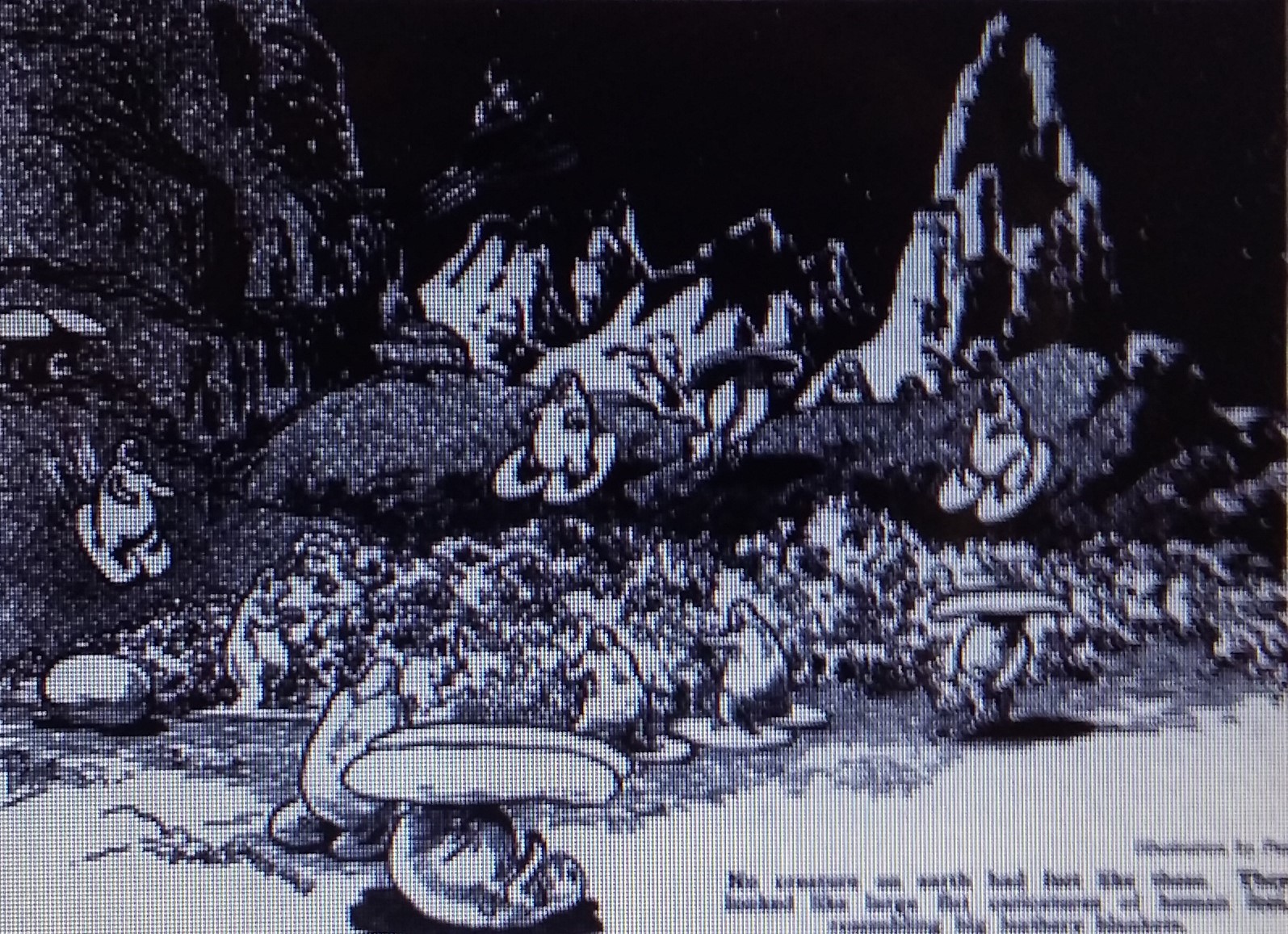

Selenite explorers tantalizing a dinosaur

Selenite explorers tantalizing a dinosaurBut also, I aim to widen the field of view, contextualising The Moon Conquerors and The War of the Planets so that this epic will shed light upon the growth of our sub-genre; how it got its shape; what other shapes it might have but did not acquire in the limited time available - the OSS "window", the first two-thirds of the twentieth century.

Stid: "Might have but did not"? You'll be getting into a counter-factual history of counter-factual histories... My head's spinning already.

Zendexor: Cool it - my theme really is simple. Namely - elbow room, or the lack thereof! Grabbing what you can in the time you've got!

land-grab, reign-grab

I know next to nothing about the great Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889, except the general idea, that settlers lined up on the border and then, I suppose at some signal like that which starts a race, rushed to grab what land they could in the newly opened territory. It’s a dramatic, powerful image to reflect upon.

Harlei: I saw Stid's mouth open, and shut again. No sound came out. He's got the point!

Zendexor: Next in my treble analogy comes what I'll call the King Rush.

Think of properly English England, when the English language had prevailed over Norman French, and the English Crown was still un-shared with Scotland; between the reigns of (shall we say) Richard II and Elizabeth I. Less than a quarter of a millennium. How many individuals wore the crown during that time?

Answer: a mere twelve!

Room for that many and no more. Imagine the self-willed souls as they queue up to gestate in royal wombs during that narrow time-frame.

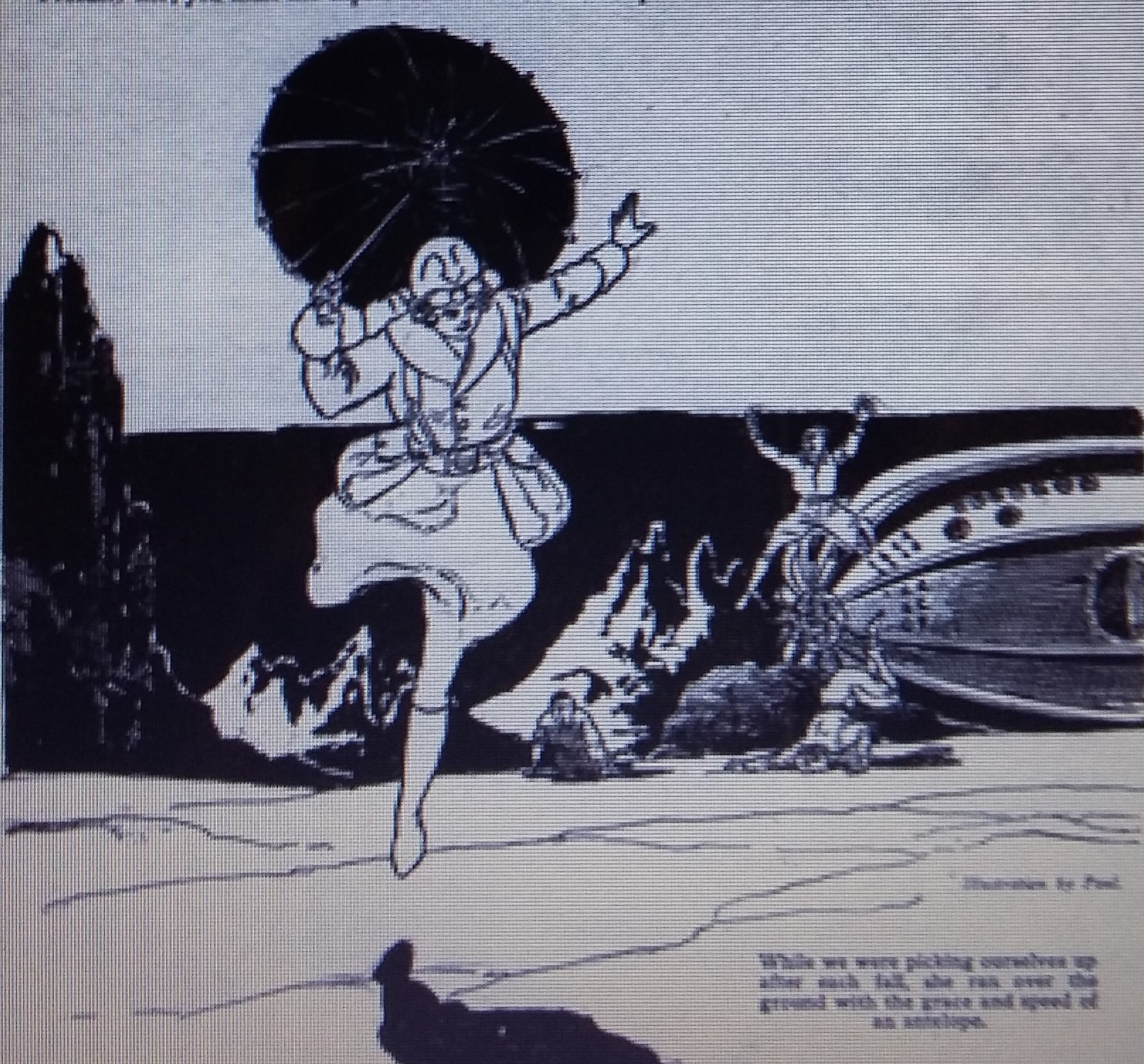

Dorothy moon-walking more successfully than Cavor and Bedford

Dorothy moon-walking more successfully than Cavor and BedfordStid: I'll put it for you less whimsically: we're talking about event-possibilities jostling to happen inside a restricted probability-area.

Zendexor: Right. Whether we focus on the Age of Kings, or on the literature of the Old Solar System, we're discussing something which lives on borrowed time. It can only last so long before historical processes put an end to it. And the allotted time is too short to accommodate all the possible personality-patterns and event-patterns - of either kingship or literature. A hopeless squeeze, especially with types that hog huge helpings of prime time, like Henry VIII with his 37 years and 9 months on the throne.

Harlei: I've often wished there were fewer Henrys and more Richards. Or even Johns. And how good if there had been a Roderick, like the one in the Danny Kaye film...

Zendexor: All right, let me sum up or we'll never get onto the Moon. The point is, only a limited bunch of possibles actually see the light of day.

scant decades

Which leads me, finally, to the OSS Space Rush.

Here again we have a sheaf of potentialities all trying to jostle their way into a limited actuality. Necessarily so - because the Golden Age of OSS literature couldn’t last more than a few decades, because science, the same scientific vision which lit it, was bound to lead to the Space Age which extinguished it.

Sure, the OSS lives on in the NOSS, but that’s another story. The "New Old" Solar System has taken literary wing, having flown the old nest of scientific beliefs. Vision and belief have parted company. But for the moment, let's consider the decades when they still lingered in sight of one another.

Consider the brevity of that golden period when science had opened up the OSS zone of inspiration which it was shortly to close back down.

Consider the consequences of that brevity.

A squeeze, a squash! Not nearly enough time for even the main avenues to get properly explored!

Harlei: We must be grateful for what we have...

Zendexor: Oh, sure. A huge outpouring of fun stories, including quite a few works of genius. But a glance through our tales unwritten page ought to make it plain that the OSS as a literary sub-genre is drastically incomplete.

And in saying that, I don't merely mean that it's incomplete in detail. I don't just mean that the branches and twigs haven't all properly grown. No - I'm saying much more. I want to make the point that not even all the main trunks have been cultivated.

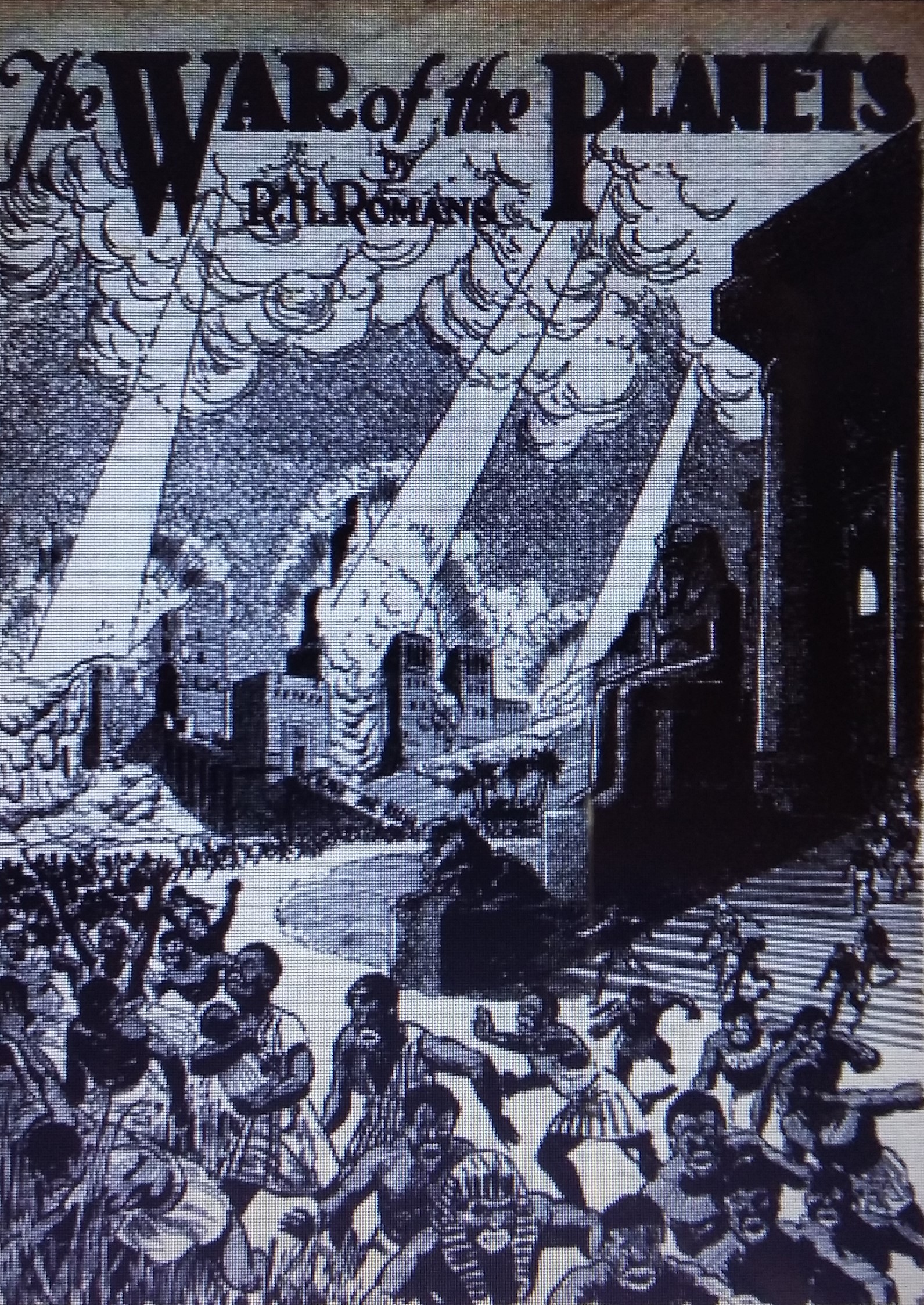

Which brings me at last to the title stories of this page, the two-story lunar epic by R H Romans: The Moon Conquerors and its sequel, The War of the Planets.

catch the hopes as they fly by

To be fair, we ought to view The Moon Conquerors not just in its finished entirety but as it unfolds; the hopes it arouses; the expectations... Ideally, then, we'd draw up a page-as-you-go expectations-map.

For instance - when Dorothy's father says to her:

"...You will find the surprise of your life when you first receive a close-up view of the moon."

"What is it? Is the moon inhabited? Is there really enough atmosphere to support life?"

(Ah, the good old days when the question elicited the right answer!) Mr Brewster replies:

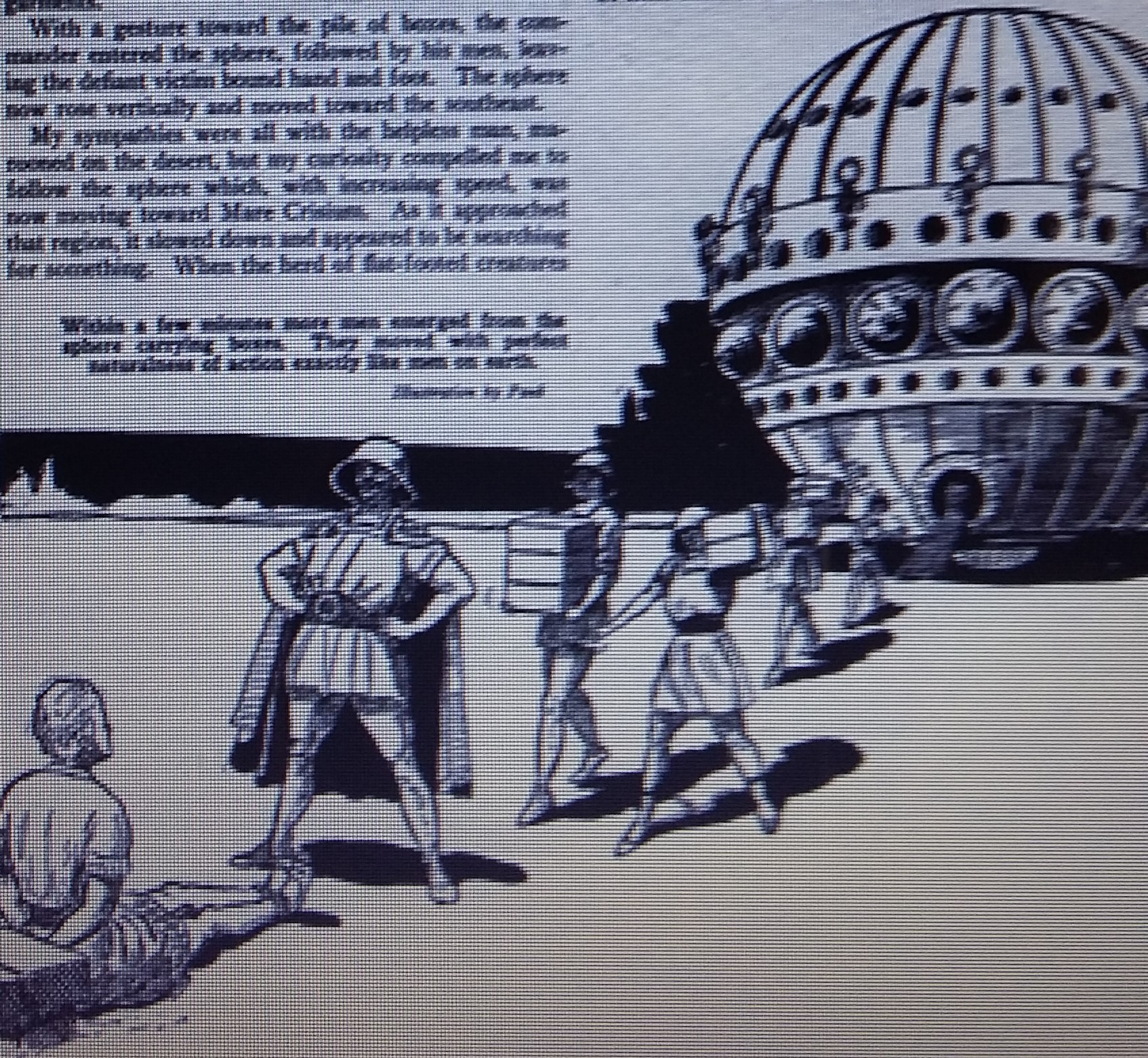

the "bideens" of the Mare Crisium area

the "bideens" of the Mare Crisium area"...I have found life on the moon and all the planets that I have examined. But it is not exactly the same forms of life with which we are familiar. Evolution, working with different materials, under different conditions, has produced different results. Terrestrial life is not duplicated elsewhere."

"Can life be found on all parts of the moon? Or is it confined to particular regions?" I asked.

"Most of the surface of the moon is desert land, but look at Mare Crisium if you want to see the Selenites."

That sentence tingles all the more, for its news of rare rather than of abundant life; its piquancy arises from the very limitation of the idea, a limitation that helps span the gulf between our image of a dead world and the contradiction of that image with which the rest of the story excites us. It would have been excessive to announce a Moon crawling with life; but "look at Mare Crisium if you want to see the Selenites" is powerful.

In the following paragraph, watch for the smooth leap of revelation in the last two sentences, when at last we look through the heroine's eyes at a life-bearing Moon -

...My first vision of the surface of the moon with the most powerful eyepiece showed an almost level plain, free from both vegetation and sand. No evidence of even the slightest atmosphere was found, and I was inclined to think father was joking when he said life was possible on the surface of the moon. I moved the lens toward the circular ring of mountains and the smooth level appearance of the surface was broken by small craters, many of which did not seem to be more than a foot or two in diameter. Their height in most cases was greater than their diameter. The surface became more uneven as the lower slopes of the mountains came into view. I could now distinguish a form of brown, grassy vegetation. A few minutes later I discovered a small spring of water at the head of a short stream, which ended by soaking into the land and silt...

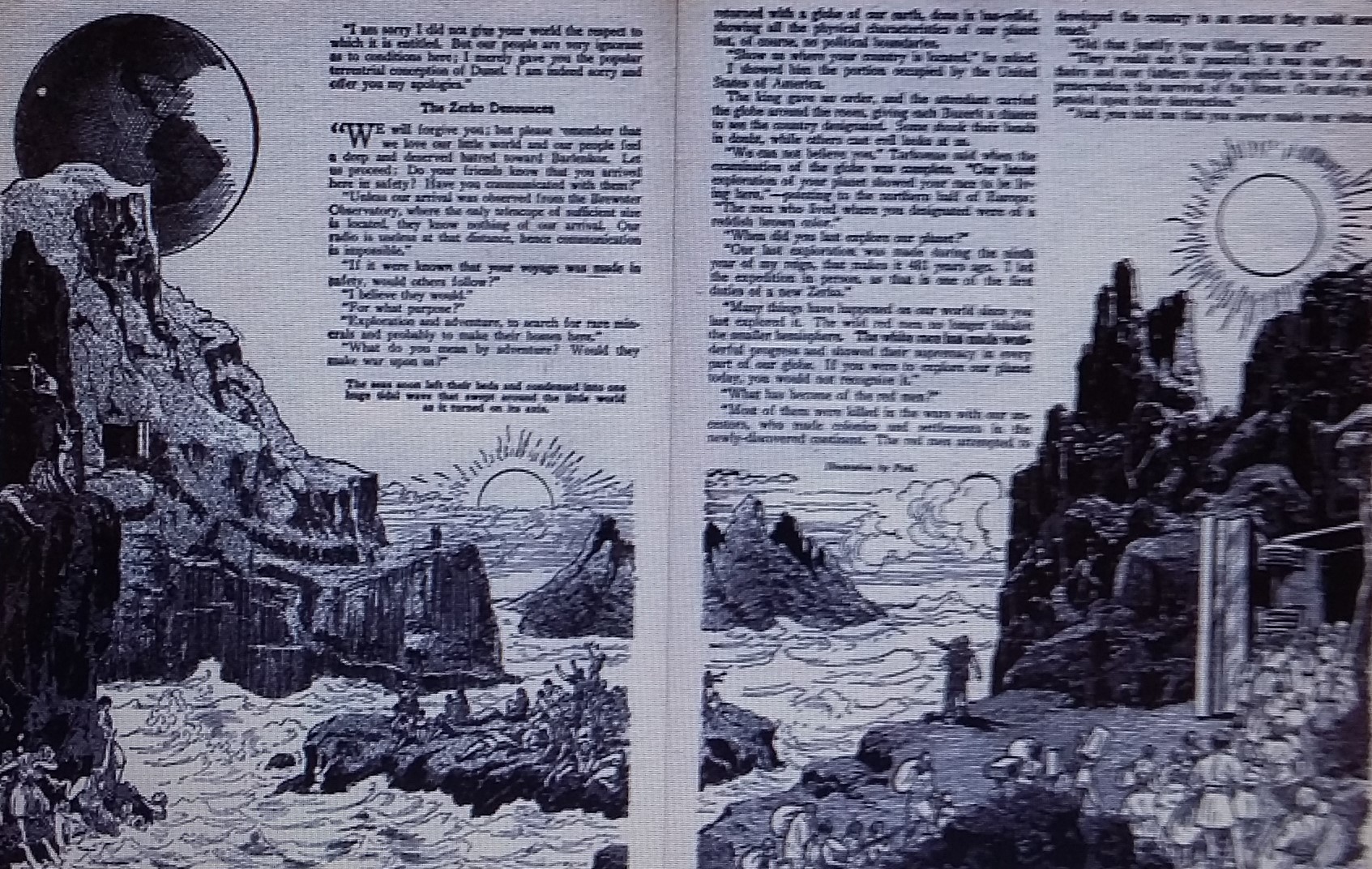

ancient lunar tidal catastrophe caused by the arrival of Barlenkoz (the Earth)

ancient lunar tidal catastrophe caused by the arrival of Barlenkoz (the Earth)From this point, as I read on, the plot kept me hooked, as it developed with a mixture of gripping and annoying features, absorption and excitement keeping well ahead of the occasional disappointments. Tedious in places, the story even in its faults retained a freshness without which I might have abandoned it. It gave me an inhabited Moon with non-human Selenites and, later, with human Selenites. Were these latter to be real telemorphs, like those of Burroughs, or would they turn out mere COMOLD let-downs like you get with other writers? For a while I was allowed to hope, and even when that particular hope was gone, it was replaced, not with some COMOLD of the triter sort, but with a more majestic, Stapledonian COMOLD, an epic of planetary destinies involving not only the asteroid progenitor but also a world which lodged in our System after a close encounter with a wandering stellar system in the distant past, plus, for good measure, the founding of the civilization of Atlantis. Mighty, world-shattering events are narrated in passages which belong to the sub-sub-genre of "invented history".

However, let's backtrack, to the presentation of the moon itself.

a sub-sub-genre lacking heirs

The notion which will most endure in my memory is the tale's excuse for allowing, despite the evidence against it, a lunar atmosphere.

In short, the atmosphere's invisible, and it's heavy.

If only this notion had been followed up by other authors!

Dorothy Brewster announces to those whom she hopes will back her proposed Moon voyage:

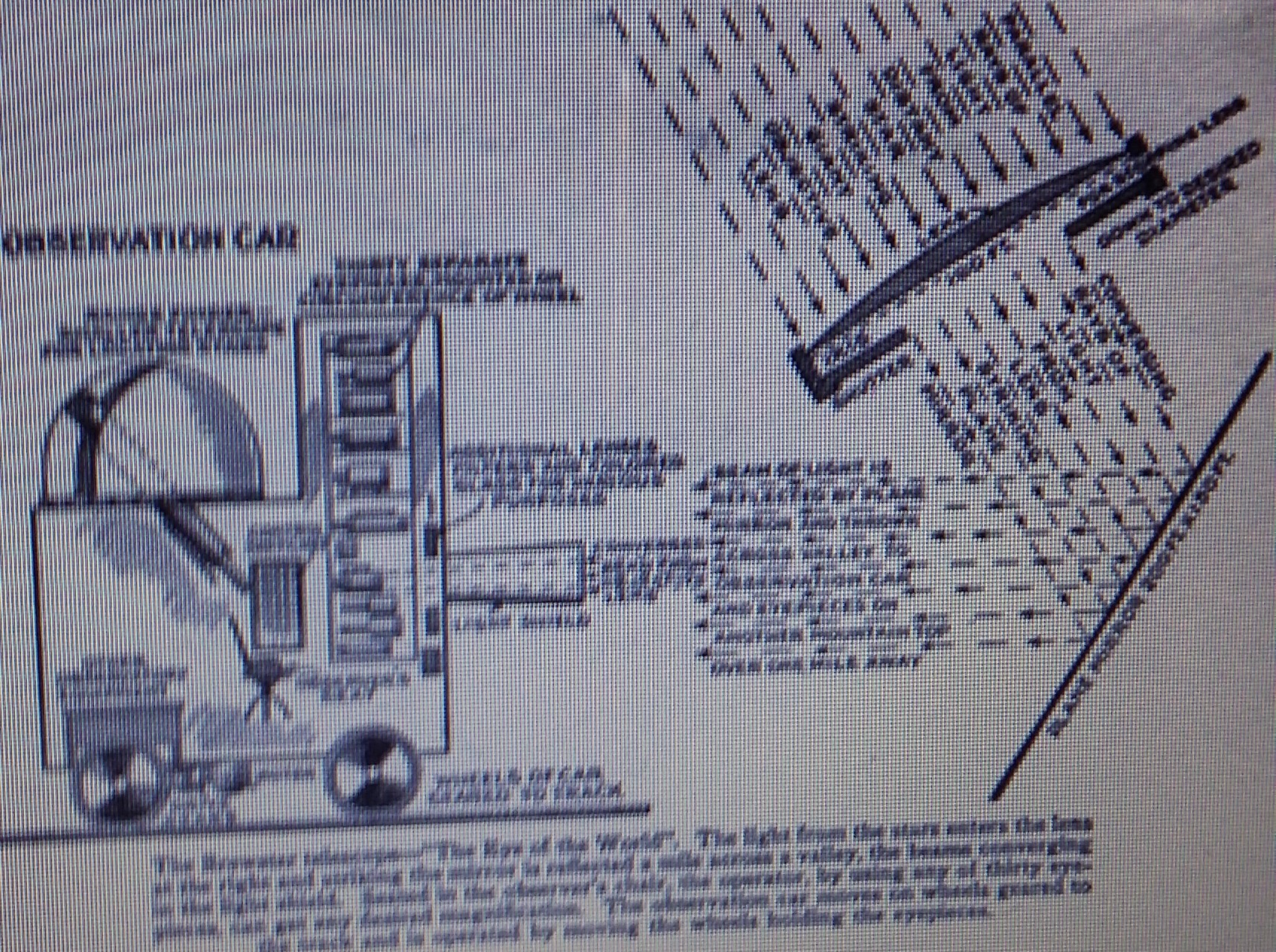

On the way

On the way"...Present-day scientists are very much mistaken as to the moon; and I have found many errors in their so-called established facts. First of all, the moon does have an atmosphere, denser and heavier than our own, although it does not contain the same elements. It contains an unknown gas, which is both heavy and invisible, as well as oxygen, or something very similar to it. But it is entirely lacking in hydrogen and water vapor, which makes our atmosphere visible. The lunar atmosphere is entirely invisible and astronomers cannot be blamed for thinking that the moon floats in a perfect vacuum when they look at it with their smaller telescopes.

"Water is not lacking, but it is very scarce. At the base of some of the lunar mountains, I have found small springs which flow for a short distance, only to soak into the ground again and return to the underground pool from which they came. No evidence for evaporation is found and I am inclined to think it is impossible for water vapor to mix with that invisible atmosphere.

"Vegetation is always to be found near these springs... This vegetation is not green, like our well-watered grass, but is of a brown sun-scorched hue. It appears in the form of grasses, vines and small trees, resembling the scrub pines of Greenland and the cactuses of Arizona and Mexico.

"Animal life of the strangest forms live here too. Australian animals look strange to the natives of North America, and those of the deep sea are stranger still; but lunar animals are even more peculiar. Bipeds are more common than quadrupeds; instead of describing them, I shall show you some pictures I took with the aid of the telescope..."

the "man in the moon" is a political prisoner

the "man in the moon" is a political prisonerDorothy is cagey, however, when people ask her if she has seen any evidence of actual human life on the Moon. The truth is... and here the story lurches into powerful though implausible romance... the truth is, our Dorothy is in love with a Moon-man.

Love at telescopic sight

Stid: Cupid's arrow smiting through a telescope - implausible emotionally as well as scientifically! But having come this far, no doubt you're going to argue that the author gets away with it.

Zendexor: Correct. For me it is indeed a case of GAWI... Besides, Dorothy Brewster is an unusually fixated heroine. The type that defeats improbable odds to get what she wants. That being so, I'm not sure you're right, Stid, about the emotional implausibility. An armchair shrink might even conclude that it's more plausible she'd fall in love with the "man in the moon", than with someone in her own society.

Harlei: Besides, "the man in the Moon" is special: a humanoid Selenite, a victim of oppression, marooned by his enemies amid a wasteland, whom she tracks as he plods ever more exhaustedly towards the destination we get to call "Mount Despair". Unforgettable stuff.

Zendexor: Indeed, if you read The Moon Conquerors you aren't ever likely to forget Dorothy at her eyepiece tracking the plodding moon-man, wondering if he is going to survive, and plotting a fantastic, incredible rescue operation.

On the other hand - and this brings me to tie up the land-rush, the king-rush and the moon-rush - it turned out that the idea of our Moon with a heavy, invisible, breathable atmosphere got jostled out of the way by all the other stories that occupied publishing-space in the decades that followed. Regrettable, surely.

But it's not too late to enjoy these stories, not too late to dream of what follow-ups there might have been - and (come to that) not too late to write them.

R H Romans, "The Moon Conquerors" (Science Wonder Quarterly, Winter 1930); "The War of the Planets" (Wonder Stories Quarterly, Summer 1930).

See the extract, A biped evolved on the Moon.