Man of the World by Robert Gibson

19: a happy childhood

Luminarium - west

Luminarium - west

The

suburb named Ganeshan, in which Midax Rale grew up, was a social backwater,

agreeably and peacefully second-rate.

His

father, Ultrisk Rale, would have done better for himself (in career terms) a

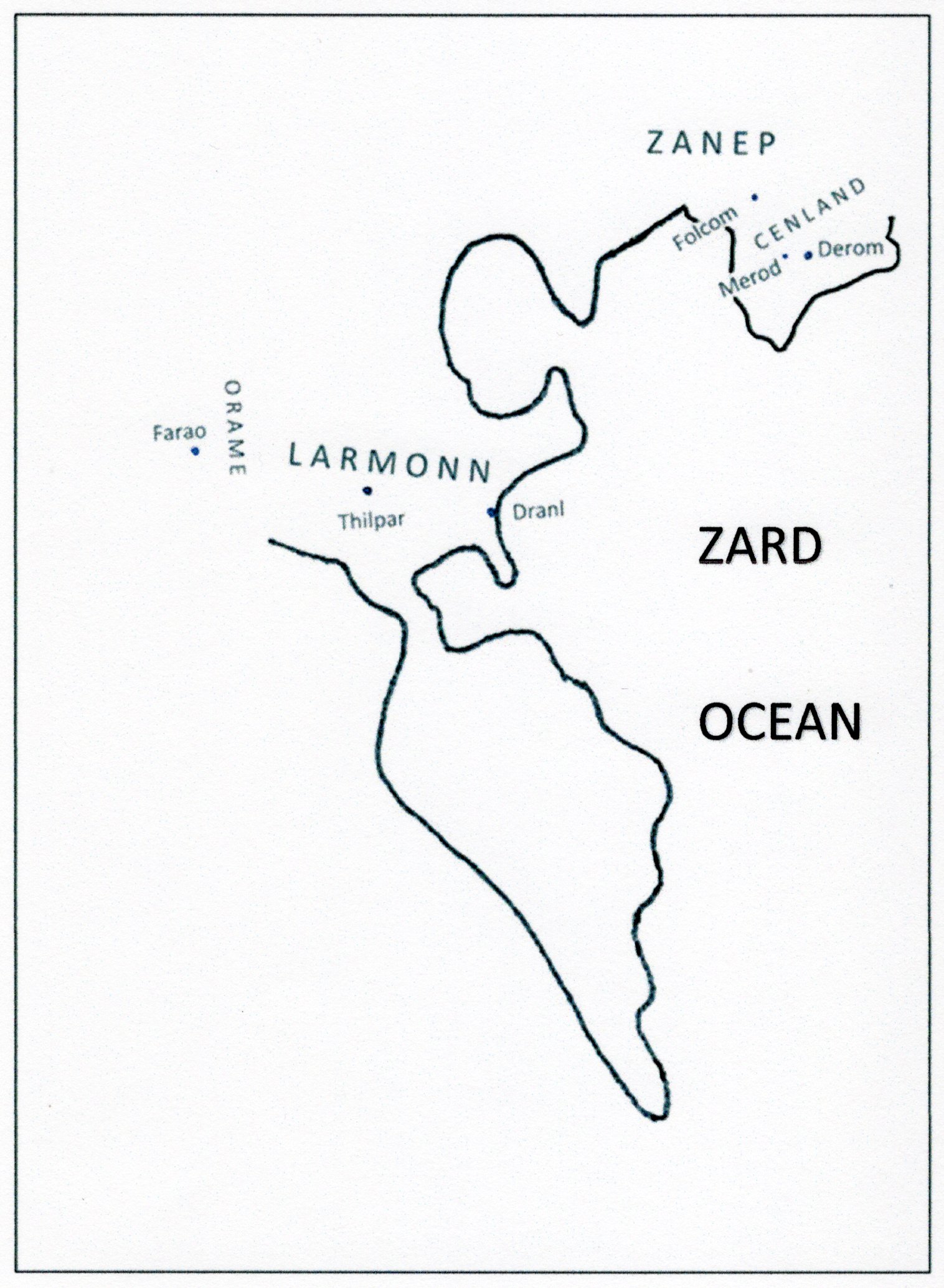

couple of miles away in the centre of Dranl, for the East Coast provincial

capital was the greatest trading city of the continent of Larmonn.

Dranl hummed with prosperity, buyers swirling through the picturesque

muddle of its commercial quarter, floods of sightseers lapping around its

dignified public buildings. By contrast, Ganeshan was quiet. Nevertheless it,

and other suburbs, shared in the prosperity of the metropolis – a prosperity

based upon its ideal position on the trade-route across the Zard Ocean to

Heism.

Ultrisk

Rale was happy in his humdrum middle-class conformity, his white-collar job in

Ganeshan. Would-be “head-hunters” who had known him at college were well aware

that he was capable of more. He had had offers of employment, not only from

organizations in the city centre, but from much further afield: he might have

relocated all the way to the continental capital, Thilpar, a thousand miles

into the interior of Larmonn, and trebled his salary – if he had wished to. Yet

he and his wife were happy to bring up their son in placid obscurity, where

life could be lived at a gentle pace. The unpretentious tree-lined streets of

Ganeshan, the taken-for-granted local shops, the greenery in overlooked copses

and dells, the scattering of weed-choked wastes, the outcrops of moss-covered

cliff left behind by the ancient shifting shoreline of the Zard – all these

ordinary idylls were storable reserves of golden memory in the fortress of the

infant mind.

One

fine late autumn evening Midax, aged six, scampered off to play outside as

usual. “Just for fifteen minutes, mind!” his mother said.

“Awright!”

he shouted back. And he ran to meet some neighbours’ children who, likewise,

had been let out a quarter of an hour before bedtime. Their mothers knew that

the little ones were nearly tired out, and that they would go to bed more

willingly if they were completely tired

out.

Midax

and his friends played “tig” among the tree-stumps in a vacant patch which they

called the “muffs”, overgrown with fluffy dandelion clocks and bindweed. Jumping

over the stumps and roots, they blew the dandelion fluff at each other. Then

came a moment when Midax happened to glance up at the western sky.

“Look at that!” he gasped.

He

had felt awed by sunsets before, but this one was extra special. It was like an

unearthly, luminous landscape floating in the sky. It was utterly tremendous if

you took it seriously, and the little lad knew of no way not to do that.

“Humm

– yeah,” said Fadron Ganol, his staunchest friend.

Midax

did not have the words to say any more. He had seen the lack of interest in

Fadron’s glance at the sky.

The

sun was sinking, Midax knew, and the vision would not last long. But all the

more did it summon him to those floating shining mountains, with their blaze of

toppling grandeur. Without question he surrendered his heart and soul to that

realm of splendour – nothing mattered in comparison with that, and it planted a

flag of undying allegiance in his young mind. He would never be the same again.

Henceforth, he knew something, though what it was he knew, he did not know at

all.

The

next day was a week-end. His mother and father took him on a trip to the

Kalbeck Forest. There he spent a happy day trying unsuccessfully to climb

trees. Once he saw a lizard. All in all, it was a good outing. Exciting, even. And

yet – it had nothing to compare with the previous evening’s ecstasy. The sight

of the sunset clouds had quietly and profoundly changed Midax for ever. Yet it

was a change that could not be remembered for long on the surface of his mind. Mostly,

his consciousness had to forget it. You could not live your life if you were

dazed all the time.

Only

when they were driving back that evening, along the dusky edge of the forest,

with Midax snuggled in the back seat and looking out of the car window at the

windy Gonesh Plains between forest and sea, did something of the mysterious

splendour return, with a silent voice – but calling from where? From out there

somewhere, yet (he sensed, uncomprehending) also from inside him. As if there

had squeezed into his insides a message from the soundlessly whispering sky of

evening, bigger than the ordinary daytime sky –

It so happened that next

day his father handed him a gift: a globe of the world.

“Shall

I teach you some geography, Midax?”

The

boy had never heard the word before, but he said, “Yes, Dad.”

He

was only vaguely attentive, out of politeness, while Ultrisk began to point out

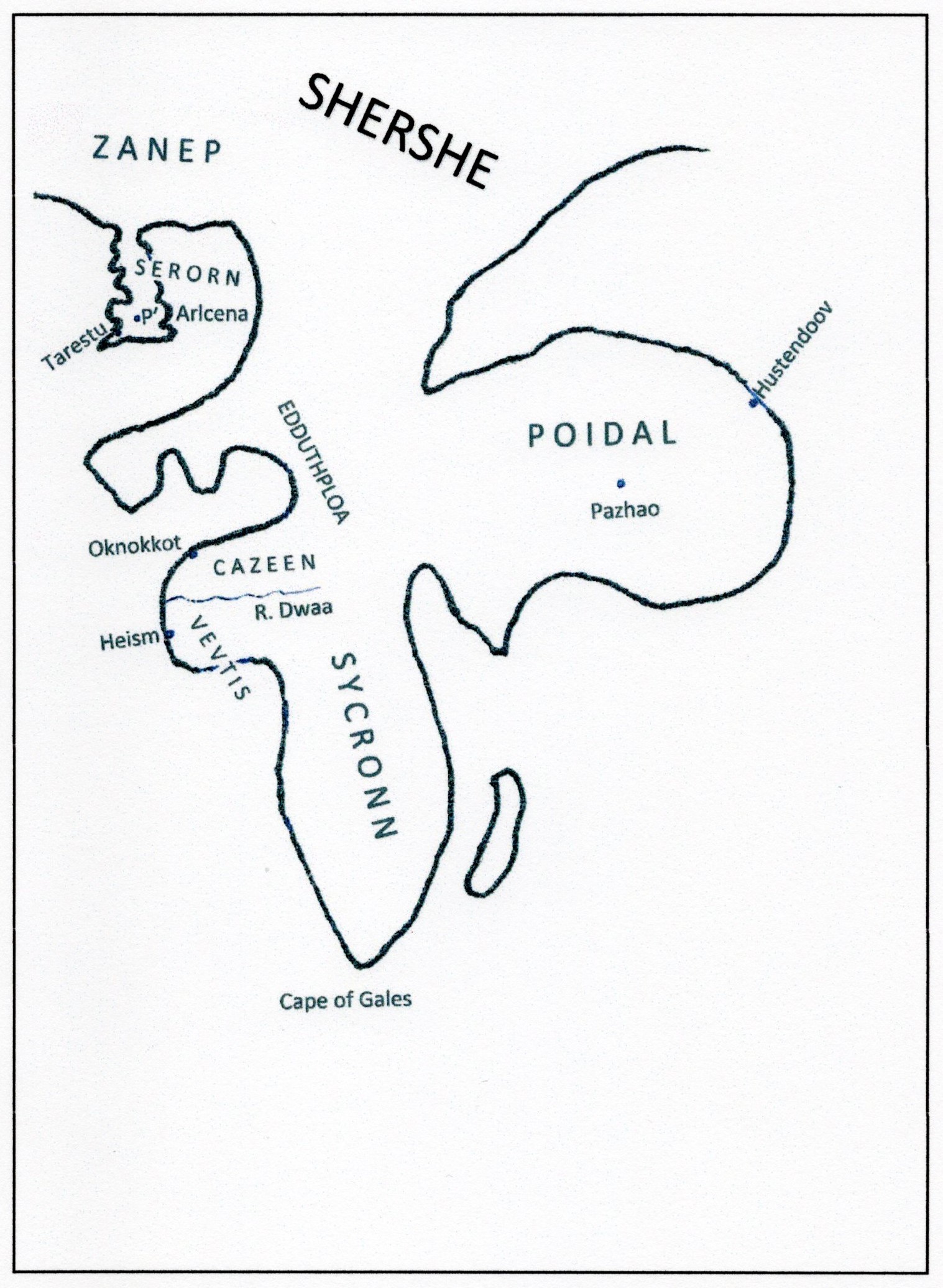

the countries on the globe. “This is Larmonn, this is Vevtis, this is the Zard

Ocean between them…” Names. Colours. They did not seem to mean much.

Ultrisk

thought, He’s a bit too young for this,

after all. Mustn’t push him.

Father

and son were sitting contentedly on a sofa in the lounge. The room as usual was

huge to the child’s eye, a room full of comfortable shadows and mysteries that

weren’t scary because Mum and Dad were there. Time stretched ahead, days and

nights to infinity, the nights marred occasionally by nightmares which,

however, had no power to infect the day… Midax’s attention wandered back to the

globe, which his father twiddled idly.

His

mother came in and she and Dad began to chat, with good-humoured disappointment

at Midax’s lukewarm reaction to the globe. “You can never tell what’ll interest

them,” Kmee said. “Look at him now,” she added shortly afterward, for Midax had

gone to another chair and had buried his nose in an illustrated children’s

encyclopaedia. “That same old page 69, I’ll bet.”

Ultrisk

leaned over to see.

“You’re

right.” It was, indeed, that page

again. The page with the clouds. “Can you say them all out, Midax?”

The

child shut the book and recited, “Culumus... I mean cumulus…”

“Yes,

go on! Show your mum what you said last time.”

“Cirrus,

stratus, um… cirro-stratus…”

“Great!

Well done!”

“And… cumulo-nimbus!”

“You’re

going to be a meteorologist, Midax!”

“What’s

that?” asked the lad shyly, suffused with love and pride at the genuine

admiration in his father’s voice.

“A

weather-man.”

“No,”

said Midax thoughtlessly.

Aside

to his wife, Ultrisk chuckled, “He’s not going

to be one because he already is one.

Instead of getting him a globe, I should have got him a wind-sock.”

She

replied calmly, “He’ll see the point of the globe one day.”

Midax

meanwhile again grasped his beloved page 69 and once more gazed hungrily at the

pictured clouds, like an explorer who sees but cannot reach an unknown

shoreline.

>>>next chapter>>>