Man of the World by Robert Gibson

26: the shapers' vow

On the

very next occasion that he could arrange to have a couple of days off work, he

made his way in the early morning to Dranl Central Station.

He

went to the ticket counter, opened his wallet and said:

“A

return to Thilpar, please. On the Continental Express.”

That was the only way. Buy the ticket and enter the train.

Wait until it began to pull out from the station, whereupon he would know that

the matter was out of his hands. So he went ahead, and so it proved: out of

Dranl and into the sunlit landscape of the Gonesh Plains, the Express began to

accelerate along the first stage of its route to the capital of Larmonn,

ratcheting his whole life forward – although of course in theory he still could change his mind at the other end.

Yes,

he could simply take the return train

and accept that he had wasted two days and the price of a ticket. But he knew

for a certainty, that after splurging money on that ticket he was not going to

lose face with himself by turning back from his purpose. So as the

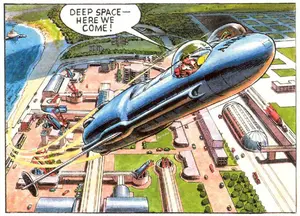

bullet-shaped locomotive picked up further speed, drawing the world’s fastest

train along the world’s most famous route, Midax sensed its forward spurt as

the casting of a die. Each time he had ridden the Continental Express he had goggled

at the onrushing Purple Range, the mountains expanding before his eyes as his

carriage hurtled towards them at two hundred and fifty miles per hour, but this time he revelled in the speed as

never before.

The

train did slow slightly as it entered the Kalbeck Forest which skirted the

Range like a dark green apron. It must have slowed some more on the approach to

the mountain tunnel. Nevertheless the trees and foothills closed in at a

startling rate; and after the darkness and the roar came the emergence onto the

plains beyond, and here the train’s velocity could really open up. Here were no

longer the hummocky and thickly-settled Gonesh Plains but the incomparably

vaster and less populated Taldon Plains stretching all the way to Thilpar at

the heart of the continent. Here, under the open sky of an infinite table-top

the Continental showed what it could do. Steadily it pushed up the velocity to

four hundred miles per hour on its elevated track, accompanied by thinly

screeching winds. For a couple of hours there’d be nothing else to see other

than the plains and some flashing glimpses of white-fenced ranch-houses and

occasional flecks of bloom from irrigated orchards or colourful

crops.

Midax,

settling back from the window, unfolded the morning’s paper.

Knowing

that editors preferred, for reasons best known to themselves, to stick the

celebrity-waffle on page one and tuck the interesting stuff deep inside, he

flipped past “Mezwa and Juf: It’s All Over” and the rather more interesting

“Waretik to Run – Official” (at another time he would have read this, but

today, somehow, it didn’t fit with his mood)… flipped the pages until his eye

caught a curious title amid the centre features-spread.

Good Trains – Bad Planes

It was by author-tycoon Davlr Braze. Midax had known him at school. Good old Davlr! Midax settled down to read. After a while he laid down the article with a reflective smile. Whoever could have guessed that the lad would develop such an aptitude for tossing off thought-provoking articles on economic matters, flavoured with armchair psychology? He looked again at Davlr’s words:

The Dranl-Thilpar Continental Express has

a one-hundred-per-cent safety record [glad

to hear of it], whereas the fledgling Dranl-Thilpar Air Link has already

suffered thirty-four fatalities. Most pundits, I suppose, will argue from these

one-sided statistics that Rail has won its argument over Air hands down,

especially as Rail has maintained its lead over Air in regard to both speed and

expense…

…No doubt about it, technological

progress is turning out lopsided. And I suggest that when we turn a blind or

incurious eye to this anomaly, we do so at our own risk. Why should the biggest

and fastest plane, half a century after the invention of air travel, still

consist of a twelve-seater propeller-driven aircraft easily outstripped by a

train? (Let it also be borne in mind that the movement for global unity and

world government seems to have stalled precisely because of these practical

limits on transportation.) For that matter, how come we don’t have low-priced

commercial flight whereas we do have colour TV? The theoretical base exists

equally for both. Yet the one gets developed whereas the other does not…

…A clue to this imbalance may lie in the

realm of the subconscious. After all, as recently as ten years ago the dead

hand of Boaloism [here we go] was

still channelling most of our spiritual energies into countless futile, tragic,

unrealistic searches for the perfect Other Half; channelling most of our

ingenuity into shoring up marriages which should have been dissolved; shoring

them up in the vain and desperate hope that they were the Ultimate… and for

such psychological aberration we have had to pay a heavy economic price. For

centuries the Boalonian Ideal played the role inside our heads that a

parasitic, idle aristocracy plays in an Old Regime society; lording it over

other inclinations, preventing any concentration of effort in directions which

were likely to dilute its authority – which meant the neglect of any

technological improvement which might give economic unity to the world; the

prevention of any striking achievement which, by shrinking distances and

forcing all peoples into the melting pot of surging economic advance, might

force them into freedom from the old introverted ideal. Which is why, crazy

though it may sound, there is a

definite, provable connection between the excessive superiority of our train

services, the stunted development of air travel, and the prolonged reign –

thank goodness coming to its belated end at last – of the Boalonian Illusion…

Phew, thought Midax after ploughing

through to the end, he’s really gone off

his rocker this time. And yet Davlr’s article was just one more in a long

traditional series of grumbles about Boalo’s effect upon civilization. Davlr,

on reflection, hadn’t “gone off his rocker”, he had merely played a variation

on the hackneyed old theme of the anti-Boalonian tirade.

A

slowing of the train: Midax turned again to the window. It was about time for

Bzenn Bridge. Here the express must cross the last slow river which meanders

down the almost imperceptible eastward slope of the Taldon Plains.

Because

of the deceleration, certain features of the landscape, speed-blurred over most

of the route, now became observable. His eyes could linger on the

road-and-field patterns called Settlement Squares, surveyed and laid out

centuries ago and illustrating, in their partial erasure by overgrowths and

obstructions, the subsequent history of Larmonn from the vantage of the train. All

so deep and real, and yet, in another sense, a mere wavering dream-quilt

tempting from Midax’s lips the lines:

I’m partial to a breakfast on

th’eternal stream,

and sometimes I would stop upon a

world for lunch;

yet what canned life could pack

sufficient punch?

(I dream, I dream, I see the end, I

dream.)

A houseboat is sufficient for

th’eternal stream,

but sometimes binoculars tempt me

to squint

at a bobbing drum whose message is

a manufactured hint

(I dream, I dream, I see the end, I

dream).

Somewhere there’s a jetty for

th’officials of the stream,

and someone may exist who might be

ready to partake

in a survey of this whole fantastic

stage for goodness’ sake

(I dream, I dream, I see the end, I

dream).

Appearing

at last over the horizon, the topmost communications towers of Thilpar rose

into view in the path of the bulleting train. Within a few seconds Midax was

able to see the distinctive outline of the capital’s skyscrapers. Javelins and

spades of concrete and glass, brandished at the sky, drew closer while the

intervening ground sank like a dropped veil to reveal lower levels. Pressure of

deceleration finally pushed Midax back into his seat-cushion, tearing his gaze

from the window. When he looked out again, half a minute later, he was already

well inside the city-centre and the train was drawing to a stop.

This

was going to be the awkward bit, as motion ceased. Now, now, no ‘second

thoughts’ allowed! And although, emerging, he staggered ever so slightly on the

platform, feeling queasy and disoriented, the moment of cowardice passed. Soon

he was strolling, his “A to Z” street-plan-cum-guide-book in hand.

It

was the same well-thumbed guidebook which he had taken on his previous visit

some years ago. He remembered the author’s grumbles at the “architectural

hodge-podge” of Thilpar. This time, as Midax strode through the cityscape, it

struck him how unnecessary such complaints were. How easy it was, if you

preferred buildings of a certain style, to “factor out” the others, so that you

only noticed what you needed to see, and thus eliminated eyesores. For

instance, if you fancied the older buildings, which were all stonier and

squatter than the modern ones, you could “de-select” the recent steel-and-glass

towers from your vision, by regarding them not as buildings but as mere mirrors

to reflect the sky and clouds. Beautifully effective mirrors they were – vying

to present you with a shining backdrop while you went nosing around the heavier

stuff…

Twenty

minutes’ walk in the direction of the most built-up area brought him to where

the throng of pedestrians spilled into a clearing in the forest of skyscrapers:

a square with glass-cliffed sides. Each side differently reflected the one

stone building which crouched at the far end: the squat yet looming bulk of the

Tramboleion.

This

was it: the Western Hemisphere HQ of the Shapers’ College. His destination

stared Midax Rale in the face at last. A moment of some fear; and yet, now that

he had reached this point, he knew what to do with his doubts.

For

he had made his choice, had he not? His purchase of the train ticket this

morning was his expenditure in the currency of freedom.

He

passed through the Tramboleion’s entrance without breaking his stride. Let the

predictable yammer inside his head continue – all the floating thoughts making

their bumpy landings –

He

leaned on the reception desk and gave his name.

The

young receptionist said, “Rmr. Arpaieson will see you in a few minutes. Take a

seat if you like.” Her automatic smile was normal for the busy unconcern of any

big city, and Midax almost did take a seat, as though he were waiting for a

normal interview, but he remained just wary enough to prefer to stand. And he

was glad of it, when he heard purposeful footsteps behind him and turned,

hardly believing, to see the round face of Rmr. Arpaieson himself.

The

Western Hemisphere Director of the Shapers’ College in person was greeting him

warmly, with outstretched hand and a sincere look of welcome. Midax in response

was suddenly upset and confused. Super-fast thoughts rattled through his head. He

wanted the thing he was joining to be prestigious and dignified and great in

the world. To be met at reception by this moon-faced little man seemed somehow

wrong. Though of course a recruit ought to feel honoured… but might it not be

more sad proof of how the College had declined, that the Director was so

desperate to ingratiate himself with anyone still willing to join?

And

yet, cheerful as a sunflower, that face looked “down” at the much taller Midax

as if to affirm, ‘down’ is the direction

I define it to be. I know what I’m doing; don’t you worry! “Rmr. Midax

Rale? Good to see you. We’ll talk in my office first. Follow me.”

They

walked to the lift, Arpaieson remarking over his shoulder, “We sent the

brochure and invitation some time ago. You must have had a long think about

it.”

The

tone remained friendly, but Midax was wary of any implied questioning.

“I

moved house just after sending off my initial inquiry,” he replied carefully. “Your

brochure was redirected. I took action as soon as I got it.”

“Oh,

so actually it was a snap decision?”

They

stepped out of the lift and into a thick-carpeted office comprising the entire

top floor. Great windows gave a breath-taking view on all four sides out into

Thilpar’s gleaming skyscraper-forest. It was quiet up here, far above the sound

of the traffic.

Midax

replied, “Snap decision, yes, when I opened the brochure and saw, contrary to

my expectations, that you had become Director.” Obeying a gesture he sat himself

opposite Arpaieson at the desk. He knew he must speak with frankness. “I was

astonished,” he added, “that you had managed to beat the trendies. It meant

that the outfit was worth joining after all.”

Arpaieson

stared, then laughed.

“You’re

a worrier, Midax! But that’s all right – it’s not much of a criticism, only of

course I’m interested in every detail of character and motive, when anyone

seeks admission. The wrong sort would sink us now, for good… So! You really

were relieved I’d beaten the ‘trendies’, eh? You didn’t think it was a foregone

conclusion?”

“I

thought I needed to worry, when Professor Twick was Director…”

“Acting

Director,” corrected Arpaieson with a shrug. “A stopgap. An unfortunate minor

episode, a chapter now closed, in the College’s history. Mind you, old Twick is

not a bad chap; we get on well personally… And by the way, you’re not telling

me everything.”

I know what he wants to know. It’s

what I’d ask me in his place. Am I here as a genuine recruit or am I simply on

the rebound from something? Playing

for time, Midax asked: “So can I take it that the College is really still true

to itself? Does your appointment mean what I thought it meant – that the

College’s ideals are not after all going to be watered down and made

‘relevant’?”

Arpaieson

leaned forward onto the desk. “So long as I’m at this post, the answer is yes.”

“And

when you go, sir?”

“And

when I’m gone, don’t you worry then either. The College has seen off many

threats such as those of the past few years. Reactionaries such as you and I,”

he grinned, “always win in the end, because sooner or later it always dawns on

our opponents that without our ideals there would be no Shapers’ College, and

although they can never bring themselves to admit this, it does make them

rather lose heart for their struggle to ‘bring it up to date’ – as they call

the process of abandoning everything that defines it. And when they twig this,

they prefer to leave. Now I have answered your question, you must answer mine. Why

are you here?”

Midax

sighed, “This is where I must admit something which will make me look

mind-bogglingly stupid.”

“In

other words, you’re a human being. More – you’re a proud human being, addicted

to perfectionist worry.”

“This

particular human being, I’m sorry to say, has steered himself through life as

follows.” Midax took a deep breath, wondering how he was going to get the next

few sentences out without croaking with shame, and continued: “Having spent my

school years in love with a girl whom I then – out of crazy cowardice – allowed

to drift out of my life (that was about twenty years ago), I almost

continuously ever since have remained true to my memory of her, in true

Boalonian style, not looking at any other woman. I say almost continuously, because just a short while ago I spoiled my

record. Or so I thought. Now here’s the hilarious part. I fell in love with

‘another’ woman who has turned out to be the same one!” Midax scrutinised

Arpaieson’s expression at this point. He could not detect any mirth. “Don’t you

see the absurdity of it? It was the same woman, twenty years older of course;

but despite my supposed twenty-year devotion, I didn’t recognize her for weeks

and weeks. Can anything in the history of this planet have equalled that for a

stupid performance? And as to Boalo’s doctrine, now, I don’t know where I

stand, or what to think. I thought (just

before this shock) that I was being unfaithful to the ideal. Now it turns out

that I was, all the time, unconsciously proving it to be true. There is only one woman for me, but I

mistakenly thought she was two – mistakenly didn’t realize that Boalo was

right; but how, if he’s right, how could I make such a mistake? Can you work it

out? Am I an exemplar of fidelity or not?”

“Tell

me,” said Arpaieson, “how did you find out it was the same woman?”

“A

chance phrase she spoke. It jogged my memory, finally. Belatedly. I suppose

that’s all I can say.”

“So

you were just slow. You did recognize her, after a delay.”

“Some

delay! Weeks! Weeks of seeing Pjerl and talking to her almost every evening. Addressing

her by the familiar form of her name, Jerre, and not even that was enough to

wake me to the truth.”

“Perhaps, though, you did

fall for two different women,” suggested Arpaieson with gimlet-eyed shrewdness,

“in the sense that the Pjerl you knew at school and the Pjerl you met twenty

years later are, effectively, two different people. Don’t look so shocked,” the

Director went on, smiling. “No, I haven’t suddenly gone heretical; I haven’t

joined the trendies. I’m not promoting fickleness. But – personalities do change, even if souls don’t. Boalo

knew this. Only the soul, the inmost qualitative identity, retains continuity. You

know that yourself – or you should. Anyhow, I now understand the motive for

your application to the College. You wish to demonstrate, by means of a

definite recorded commitment, that your era of confusion and vacillation is

over.”

The

Director sharpened his voice as he spoke these words. Midax flinched, looking

away from Arpaieson’s face. Out of the nearest window he preferred to gaze,

into the middle terrace of Thilpar’s forest of skyscrapers. It was as if he

must measure a jump for freedom… but that was nonsense: freedom and commitment

were not opposed. No more than money and purchasing were opposed. The one

existed for the other. He looked back at the Director. Ah, good, the man’s

expression did not match the momentary severity of his tone. And the tone

itself then softened:

“Perhaps,”

Arpaieson went on, “the reason that you, when you were a young man, just out of

school, allowed Pjerl to ‘drift out of your life’, was that you were scared of

putting the ideal to the test of reality.”

“Like

I said, I was a coward, and I suppose that means I didn’t have real faith…”

“You

mean, real faith banishes cowardice? Maybe. But there’s more to it. Maybe you

knew all along that no one could possibly live up in practice to the glory

which you had glimpsed in her, or rather, glimpsed through her.”

“No,”

decided Midax after a moment’s thought, “I can’t make any subtle excuse for

myself. I was a drip, and a coward. But now…”

“Yes?

Now?”

“Nowadays

I am readier to risk a gamble.”

“Ah-hah.”

“By

that I don’t mean,” added Midax hurriedly, “that I view an application to join

this College as a gamble in the sense of having any doubts about the truth of

your teaching. I may not understand where my experiences fit into it, but…”

“Of course, that’s not where the gamble lies,” agreed

Arpaieson. “I expect you, and I, and all College members, have the same general

ideas about Truth; that’s why we’re here. But it is possible for a thing to be

true and yet still not be a particular part of your destiny. You are gambling

with your practical destiny. Shall I

tell you about my own case? About how things turned out for me? I always knew,”

continued the Director reminiscently, “that this College was right for me. At

school I was jeered at because my first name, ‘Rermer’, sounds so much like the

title ‘Rmr.’; so they chanted ‘Rummer Rermer’ at me, but the interesting thing

is, I did not greatly mind; the mockery, while it irritated me, never hurt me;

in fact it played a useful part in my life. It was a sign, a portentous sign,

that my schoolmates should thus chant more truth than they knew.”

Midax

was silent. Arpaieson saw, for the second time, a shocked look on the

applicant’s face.

Quickly

the Director added:

“You

think it trivial to suggest that some silly schoolboy name-calling could

constitute one of the operations of destiny? Not so. Boalo himself was never

naïf about the agencies which destiny can use. Here in the College we aim to

develop a unified causation theory, wherein there is no ultimate distinction

between chance and design. Come, it’s time for you to make your Vow, if you are

going to do it today.”

Surprise

at the Director’s sharp intensification of the pressure was swiftly followed by

acceptance on the part of Midax Rale, for the Director knew that the applicant

at this stage wants to be hurried.

Midax

indeed impatiently desired to get it all over with, to get past the

decision-process. So as the Director rose from his chair, the recruit followed

willingly.

Within

a minute they were down one floor and in a larger room, occupying a wider level

of the building. It felt even emptier than the Director’s office, although

there were a few clerks seated close to the walls.

A

recognizable place. The Hall of the Cascade…

The

last time Midax had seen a depiction of it – in some weekend newspaper

supplement article – the photo had made the place look plain and dreary,

incapable of inspiring awe. By contrast, the reality impressed him. Yet it was

also worse. The silence and emptiness of the real Hall set his nerves shying.

A

sort of psychic smell, as of the site of a disaster, where a crowd of ghosts

kept vigil. The tomb of idealism, perhaps. Antiquated ideals, buried in this

giant museum.

The

floor was level, yet somehow made one think of a four-sided amphitheatre with

its circular pedestal down in the central pit where, in the old days, the

applicant was supposed to stand as he spoke his vows to the massed audience of

Shapers.

No

massed audience today. Little of the old procedure had survived into the modern

age. Midax must speak his few words into a humdrum recording machine, witnessed

by the Director and four clerks, and that was all.

And what about

the original College headquarters in Serorn, the one Boalo himself set up? It,

nowadays, is in truth a museum and only a museum, emptier than this. And

won’t this one go the same way? Before many more years have passed? Am I not

about to pledge my word to a lost cause?

Pledge my word to the grandeur that

was Serorn, the Middle Continent, the cradle of mankind; and to Boalo its

greatest intellect. And to all the rest of its ancient glory, packaged and

powerless and dead. And to Serorn’s capital P’Arlcena, where Boalo’s original

College was built, a College which, so far from Shaping the world’s ideas any

longer, now subsists from tourism. Rich people drop in during their skiing

holidays… ‘dude philosophers’…

“You’re

worried,” said a nudging voice beside him, the voice of Rermer Arpaieson again,

the experienced guesser of applicants’ thoughts. “Worried that the world may

not take much notice of us. Well, yes, but it will never take none. And always, silently, it will have

to admit – by the way it respects those who keep the Vow – that we are right to

say what we do. Now you stand here. Take this sheet of paper. I’ve filled your

name in. Read the text, press the switch and say the words…”

“…I,

Midax Rale, vow always to aver, in conduct and in word, that for every human

being there is one true love per life, and the decision of romance is final.”

Click – and the voiceprint record was

sent along branching wires, copied and copied again, transmitting to every

branch and office of the College in the world, and also to the municipal

offices in Dranl, the words which could never be retracted, putting Midax on

record as declaring his belief in the doctrine that for every man there was one

special woman, for every woman one special man, the destined Other Half,

existing from before the world, perhaps from before the commencement of linear

time itself… One could not but wonder how many who had made this awesome Vow

still really believed it… but I cannot

help but believe, thought Midax. I

have been walloped by this truth.

That, after all, is why I am here.

>>>next chapter>>>