rescue on dione

by

robert gibson

"All right," said Agent Henrik Clerf, his tone solemn. "I am ready."

"Then," said the smooth Oxford-voice beside him, "we hover - and we listen."

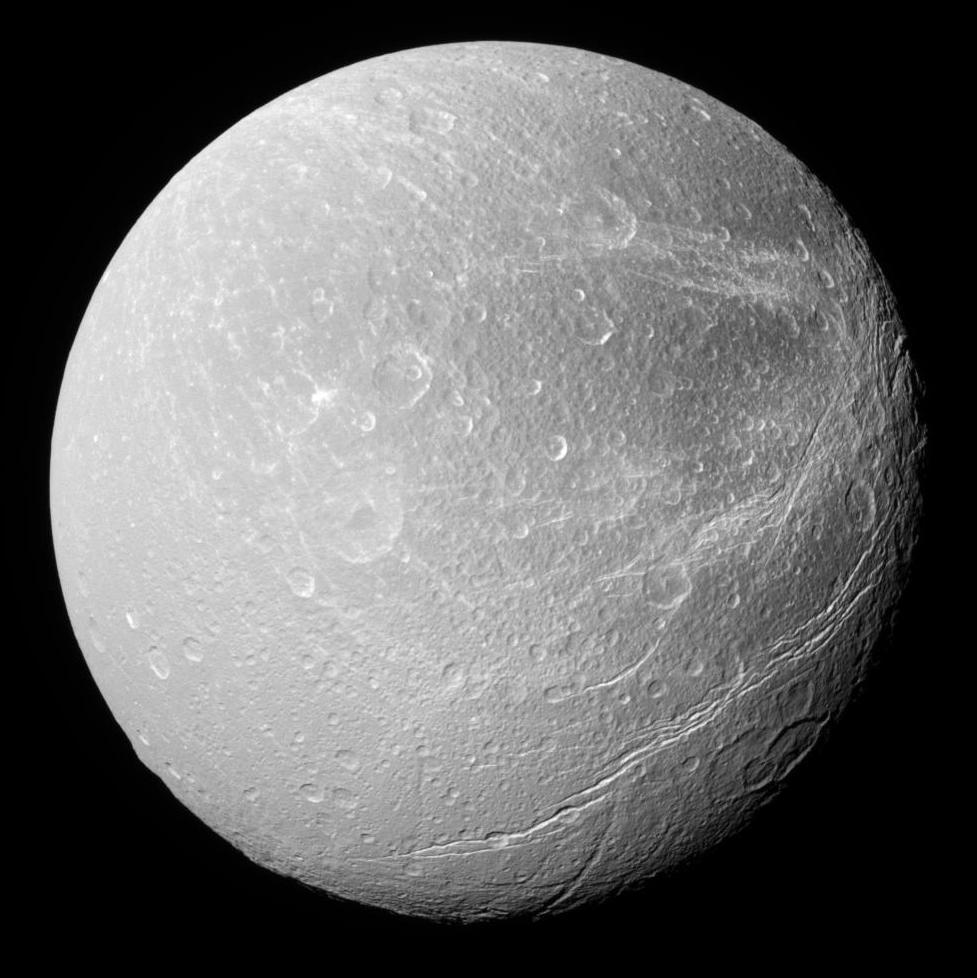

Clerf flicked a control. "Done. I'm listening." He glanced at his companion, at whose direction he had just established a parking orbit around Dione.

The creature balanced on the co-pilot's seat could not sit; it had no joints. In shape rather like an upturned Wellington boot covered with shaggy wool, it could only hop and spring onto human furniture. But its limitations were more apparent than real. Void of external feature, it yet strained forward as if vigilant with an eyeless stare.

The lords of Mimas were respected for their wisdom, their linguistic accomplishments and their senses of perception. A novice Terran Intelligence Agency operative could not but feel honoured by Hriri's presence.

As for why a Mimantean should wish to accompany a novice agent on his first mission - well, a reason must exist, but was shrouded in a not unexpected secrecy. The need-to-know principle was as old as the idea of a secret service.

Henrik was happy to start his career on a low rung; happy to be here at all. This, he thought, is life! Hovering in space fifty miles above Dione in a flying saucer!

That antique phrase was dear to his young heart. A classic-film buff, he doted on ancient movies like The Day The Earth Stood Still and Forbidden Planet. To him it was a cause for celebration that the actual builders of most modern spacecraft had seen fit to conform to the saucer design, whose practical advantages, by a stroke of luck, chimed in wonderful agreement with Henrik's fondness for the style...

Then came the moments he knew he would never forget. A sound, from he knew not where, began to skewer his eardrums:

...goa-gor-RIPP-zak...goa-gor-RIPP-zak...goa-gor-RIPP-zak...

Whatever future missions he might carry out (assuming he survived this one), nothing would equal the pristine thrill of today's event. In a state of humble joy he awaited whatever crumb of meaning might dribble his way from the alien four-beat rhythm, which certainly wasn't being produced from anywhere inside his small vessel, nor was it coming through the radio; it seemed, impossibly, to be throbbing out of space itself, doubtless via one of those local physical laws that beset the Saturn system; and he, Henrik Clerf, was privileged to experience the anomaly.

...goa-gor-RIPP-zak... the beat thudded on.

"Keep your eyes on the window," murmured the Mimantean.

Henrik gave a start; perhaps, he thought, my lids were drooping a bit; he shook his head and told himself, concentrate on reality, on the wonderful actual Universe visible through the windows adorning the 360-degree circumference of his spacecraft: especially the grey-white veined marble of Saturn's fourth moon, that hung invitingly in space as if within arm's reach of the pilot chair...

Diameter: 697 miles. Surface area: 1.53 million square miles; what you'd get if you added together Argentina, Turkey, Italy, the Netherlands and Denmark. Atmosphere: too thin to be breathable by humans, but quite sufficient for its few hundred inhabitants: the tough, truncated-pyramid-shaped wheeled beings who skated in slow, mysterious formation over the icy plains and apparently drew sustenance from the ground or the ether, or both. Not much had been discovered about their culture. They travelled only rarely to their neighbour moons, and in common with other denizens of the Saturn system they appeared to have no interest at all in the cosmos which lay outside it. All the intelligences of Ekalap - the realm of the Ringed Planet and its moons - believed that their own "universe" furnished sufficient range and wonder to last them till the end of time. And who would wish to contradict them? Certainly not the people of Earth. In particular the TIA was more than happy that the mighty Saturnian bloc showed no urge to expand or to seek the hegemony which (so men suspected) they might easily attain. More than happy, in fact, that Ekalap chose to ignore Earth...

Yet, inconsistent with the above data, was one gritty datum recently acquired by the Terran authorities:

Some folk on Dione have sent us a call for help...

...goa-gor-RIPP-zak...the third element in the beat grew louder or deeper, and now it began to be accompanied by a visual effect. The orb beyond the window was flickering. "Believe what you see," advised the Mimantean, "for your life will depend on it."

Obediently the Terran trusted to his eyes. Keeping them focused upon the increasingly shimmering satellite, he recalled another of the Mimantean's cryptic remarks: Just as your God is said to 'temper the wind to the shorn lamb', so the forces that jostle among the worlds of Ekalap are apt to nudge mercifully the occasional innocent traveller. But you have to co-operate. You have to believe.

Well, he supposed - he could only smile and hope - that he did possess some suitable quality for the job he'd been sent to do.

But now the four-note beat swelled into a roar, in which the third note became dominant both in noise-volume and in brighter accompanying flashes. Until suddenly -

The noise and the flashes ceased, and the world beyond the window appeared transformed, no longer a veined marble sphere, but a gorgeous blue ball. Henrik gasped.

Hriri's shaggy brow rocked sideways against him. "Snap to it! We must go down!"

"But - what - "

"You're doing well. Keep in time with the Third Beat. Never mind how you're doing it - you're doing it. So. What you're seeing is Dione's troposphere, which is about eighty miles deep. The pressure at the surface is about three times Earth-normal but that's not too intense for a healthy fellow like you. The main thing is, you'll be able to breathe it safely. And it's reasonably warm from the bsoo effect, the three-grav microflames. Now let us go down!"

Henrik listened to the jargon and the exhortation with one part of his mind while he attended to the ship's controls; the saucer began the descent from orbit and spiralled down towards the surface of the incredibly bright, blue little world.

In the first spare moment he asked:

"The version of Dione we thought we knew - it was, I suppose, an illusion?"

"There is no such thing as illusion."

"Please, Hriri, let's not quibble. I need to get this straight before we touch down. If not 'illusion', then an alternate world. We've skipped dimensions - right?"

"You know better than that." The plummy Oxford voice flowed more incongruously than ever from the mouthless upturned-boot shape of the Mimantean. "Reality is all one."

"I know better, do I? Look, come on," Henrik's voice became grimmer, "we've only got minutes before touch-down - "

"You know more than you realize," said Hriri. "That's why I recommended you for this job."

Henrik was silent. He did not wish to get into a fruitless discussion about what the Mimantean sage might mean by "know". Probably, he guessed, it was some abstruse allusion to temperamental suitability. Too late to map it out now. Doubtless, in one's dealings with the oracular sages of Mimas, it was always too late to catch up with their insights; however (thought Henrik with a resigned shrug) it ought to remain possible - from within the fog of a mere Terran brain - to choose how to act.

The view of Saturn and the starry sky had disappeared, and the windows showed a featureless blue glow; the saucer, nearing its goal, sank through dense atmosphere. Henrik was relieved to note that the thick blue air did not hide, though it tinted, the rising features of the landscape.

Details emerged against the bluish grey ground: its flecks of red and green became identifiable as vegetal pavilions on oblique, wide-straddled stilts, which allowed through-ways underneath and between. Some cracks in the ground might be artificial fissures or natural rilles, crossed by plentiful bridges. A mound of complication, briefly glimpsed before it receded over the curve of the world, had the size, dignity and regularity of a city. As the ship lost more altitude

a very few dots, about five or six, which might be native wheelers, could be seen in motion, till the field of view narrowed and, like the city, they vanished beyond the horizon's tightening noose.

Henrik would have preferred more time to digest all this, but he had about a minute in which to examine the scene in detail from the air before the vessel touched down on a flat area surrounded by some of the "pavilions". They stood ranged against that almost dizzily close horizon which hugged any small moon.

"And now I suppose we signal the Dioneans," he said to Hriri. "And they send emissaries... No?"

"You are making assumptions, Hinrik," chided the other in a softly amused tone. "Let us first go outside."

Almost, the Terran agent grumbled. But he pressed the button that opened the locks and extended the ramp. The denser Dionean air wafted in; he whiffed its high oxygen content and, without further preparation or comment, walked down to the moon's surface.

His boots scrunched on the pebbly ice, interrupting an eerie, whining silence. He halted and listened carefully, but sensed only his cheeks being stroked by the heavy breeze. Turning, he set off to stride around the ship, and as he did so he experienced the swaying sensation a walker must feel on the smaller Saturnian moons, where the force known as "gravity-three" cleaves close to the surface and diminishes sharply with every yard of altitude, so that your lower legs are the heaviest part of you, while your upper body, comparatively, floats at anchor.

On all sides of the ship, the views showed him no sign of any native, no movement at all except the to-and-fro sway of vegetal pavilions, a furlong away and more.

He guessed he now understood the reason for Hriri's dampener on the idea of "signalling the Dioneans". Of course, the natives were not going to risk breaking radio silence, any more than he himself could have risked landing his ship in full view of their city. It occurred to him, not for the first time, that his instructions for this mission were oddly casual. It was as if the Terran authorities were reluctant to get involved, though unwilling to give a flat refusal to the distress call.

Oh well, nothing for it but to sneak around on foot... "I've got the bearing of the city," he said to Hriri. "We'll descend into that rille," he pointed, "and keep under cover. Might as well set off now."

"You set off," the Mimantean replied. "I have other things to do."

A pang of disappointment robbed Henrik of speech for a few moments, but then he reflected, wryly, that he had, a short while ago, felt some annoyance at being "nursemaided" by his high-status companion. Well, one can't have it both ways - helpful guidance and solitary independence.

"What are you going to do?" He felt he had the right to ask this.

"Physics," the Mimantean replied. "The local laws of Ekalap are a long way from being completely mapped, and this little world has force-contours enough to keep me busy for a lifetime. But we can keep in touch. The invaders won't have cracked our scrambler code yet."

Ceremonious farewells were not in Hriri's line, Henrik knew. So he turned his back on his ex-companion and set off towards the nearest rille, which promised to lead in the direction of the city.

*

I'm on my own. I don't know enough; but no agent ever knows enough.

After all, I suppose, an intelligence mission for which one had been fully briefed would not need to be undertaken at all...

My route looks straightforward at any rate. Here is the edge of the rille. From this close it looks quite shallow; like those of Earth's Moon, it has quite a gentle slope down to the bottom of the sunken road. A road built by Nature, but almost as even as any metalled way.

I easily descend. Nothing much to see down here. Bright enough, but lacking in detail. Just floor and sides, of the same ice-rock mixture as the plain above. But without the vegetation. The only breaks in the monotony come every couple of hundred yards or so when I pass under an ice-bridge. These are plainly not the work of Nature; their ribs and buttresses are of load-bearing design.

After about half a dozen of these overhead structures I get tempted by the idea that by using one of them as cover I could creep up to have a look at the lie of the land. Could see how far I've gone; could see "what's cooking", if anything is.

What prompts me is, I am starting to notice red dots in front of my eyes. Turning my head from left to right causes the sparky dots to move accordingly, evidence that they really exist in the air around me, and that my eyesight is not at fault. Something is going on up on the surface.

I ascend, and peer from under the bridge at the join between it and the side of the rille.

I've come a noticeable distance around the curve of this world. Beyond the vegetal pavilions and some cloudy redness, a city is now visible on the horizon.

It must be Erzent, the city I want to reach; that's the only one of Dione's four which is situated on this quadrant of the globe.

I begin to notice that a faint but shrill sound is stabbing at my ears. It's a pleading whine, which I don't like. I can, however, endure it. The soils or crusts of Saturnian moons are known to possess a vast range of radiative properties, and it will take centuries of study before they are all understood, and that's nothing to do with my job; I must concentrate on my own task which, right now, is to get into that city, for the folk of Erzent are the ones who sent us the request for help.

A pity they couldn't give more details. A pity that apparently all they could risk was a quick radio burst to the TIA ship Lifeline during its orbit around Saturn.

Because of that, they'll have to be satisfied, preliminarily at least, with Despatch Grade Agent Henrik Clerf.

Now, back down into the rille before I'm spotted by any Tethyan invaders...

I have actually not yet seen any of these invaders, at least not close enough to identify. Nor, for that matter, have I certainly glimpsed any native Dioneans (or "Sreppans" as they call themselves); this little world seems largely empty.

Well, that agrees with what I've heard... that the population of each of these tiny moons is only in the hundreds. With that thought comes another - that it's becoming increasingly difficult to take this job seriously.

But, after all, it is a job. One must take precautions and advance with care, even on what's probably more of a trainer than a real mission.

Moreover, even if it fizzles, I'll write it up carefully when I get back. My report will be as complete and as useful as I can make it, so, for example, those squeaky red flashes which faintly sparkle and stain the air will definitely get a mention. In showing the Company that I can cope with weird weather I'll also be listing a nuisance that needs to be noted for future visits.

More hours gone by. More distance covered. More bridges passed over my head.

Now it's time to go up again, otherwise I may miss the right way into Erzent.

So, up I go, hoping to see the city much closer, possibly within range of a short dash. Aaaaah... here I am. Sputtering Space!

Before my eyes extend the city and its enemies. The panorama, flaunting its scary wonder, leaves me almost unable to move, hardly able to contemplate the crossing of that last half-mile. Nevertheless, ought I to wrench myself into motion, to make that dash?

I don't think so. Better not risk it unless I'm forced. Looks like I have time. I haven't been seen. I don't need to make any urgent move.

That circling gun... and those seated cones... looks like a neat standoff.

The cannon is a barrel maybe three yards wide and thirty yards long. I can see it's set in a forward-hunched parallelipiped mounting which (I am fairly sure) must be moving on a rail. Or maybe the rail itself is moving. Anyhow, the gun is now disappearing behind Erzent. I crouch, spellbound, guessing it will soon reappear on the other side of the city. A couple of minutes go by - and then, lo and behold, it does reappear. It's being taken all around its orbit in about five minutes. For about a quarter of an hour I continue to watch the weapon circle three times around the half-mile-wide city, pointing outwards to aim at one enemy after another in the circle of besiegers.

I wonder about that steady, purposive gun. Alone, how can it be enough? But then I wonder about the besiegers too.

Erzent's enemies, conical watchers, about eight feet tall and six in diameter, are spaced at intervals of about a third of a mile in what must surely be a complete circle around the city, although naturally I can only be sure of what's in my field of view. Each hulk is motionless, its legs hidden under the mass of its body. I can't see their faces; the ones which would be close enough have their backs turned to me.

Given that they're so absolutely still, can I reasonably risk an attempt to dart between them? Might the advantage of surprise allow me to rush across the mile-wide gap between them and the city?

I crouch, thinking, weighing the odds. But they're unknown odds. I can't know what weapons these Tethyans have. Nor can I guess how fast they can move. But certainly I'd have no cover: no vegetation grows in the clear space between them and the city.

If the reddish mist were denser, I might risk it. The sparks, swarming in concentration around Erzent, tint the scene, but not enough.

I wonder about them too. Their mosquito-like whine has subsided in my awareness to a drone which I have got used to ignoring, almost all the time, though just now it fancifully occurs to me, that it's like a wheedle, trying to cadge sympathy for this little world.

Suffering Space, how much longer do I watch before either I advance or I retreat?

I feel a soft vibration at my wrist: my communicator announces an incoming call on the secure channel which means it has to be Hriri.

It is. "Are you well?" he asks in that cultured voice of his.

"Yes," say I, shortly.

"Are you sure?" he says.

The inanity of it grates on my nerves. I snap back:

"What are you driving at?"

"No flickerings? No gaps in the vision?"

"None," I say truthfully. "My eyesight is steady. Why, shouldn't it be?"

"You're doing well, then," says the Mimantean. "A lot of other explorers in your place have got 'gap-eyed' by this stage. But you don't know what I'm talking about, and perhaps that's just as well, considering how precarious your present position is."

"If you're trying to un-nerve me," I grumble at him, "you're succeeding. I have arrived at Erzent, I see it's under some sort of siege, I need to reach the city without being seen and I'd rather you were a help than a hindrance."

"Oh. In that case..." Hriri's voice drawls, hesitantly. "Perhaps you might risk some gappiness after all."

I grind my teeth. "Explain!"

"You'll be all right," he reflects, "so long as you continue in the third-beat mode whenever you draw breath. Reflect on what I've said, and risk those gaps. Terrans in these parts all have to learn the trick, sooner or later, but it's not the sort of thing you can train for; no use trying to practise beforehand. Just do your best and hope for the best. Bye for now."

I'm about to lose my temper completely, explode with ire and terminate the conversation with an oath - for it seems obvious that, for reasons of his own, Hriri is merely playing me for a mug. Then, all of a sudden, I see something...

No less than a transformation in my grasp of the scene.

How could I have been so dim-witted as to miss the theme of the "persistence of vision"? I, of all people - the old-movie buff! The frames in a reel of film are all discreet pictures - they don't really move but our sight supplies the idea of smooth, fluid motion when those pictures rapidly succeed one another before our gaze.

It's just one instantaneous leap of comparison between that truth and the physical truth that Time is granular, quantized, instants succeeding one another like frames on a reel of film.

And if, in a reel of film, every fourth frame were quite different from the others, in an independent sequence, and if it were possible, when projecting that reel of film, to adjust the projector so that only those one-in-four frames, only the RIPP in the goa-gor-RIPP-zak, were shown and the other three in each quatrain were not, you'd be inhabiting only that 'movie'... that of the blue-atmosphered, humanly habitable Dione.

Every fourth quantized instant on Dione's time-line is devoted to that sequence, in which a man can walk unprotected on the satellite's surface, as I am doing.

I see it all so clearly now! No wonder Hriri was anxious that I "continue in the third-beat mode". Otherwise, I shan't draw be able to draw breath.

I feel ashamed at not having clicked much sooner. Field operatives are supposed to be all-rounders. Our stock-in-trade: interdisciplinary thought-habits.

Oh well, maybe I shouldn't be too hard on myself, since metaphoric resonance has only recently become a science. I was slow, but not too slow to be still alive.

Hriri, at any rate, hasn't seen fit to rebuke me. In fact, it seems, my affinity with the "beat" that is keeping me alive has earned his approbation. He's waiting for me to progress. He expects some action from me...

It will have to be action based on what I assume is his hint, that I can dodge the Tethyans by sneaking around the sequence of frames...

My belated grasp of the situation has, perhaps, given me the confidence to try.

*

I could wait for a better moment to come along... but what's the point? Do it now. Focus the time-sense, in such a way that I step out of the sequence of every third instant out of four, and, instead, inhabit only just enough of those to enable me to breathe, while I mix them with the dark cold lifeless sequences which will hide me as I run.

Here goes. Grasp, O my will, grasp the line of moments, in the manner I cannot describe in words but can, I trust, instinctively perform.

Heaven save me, it works straight away, the sky flickers darkly: my throat constricts: I pant from the reduced yield of the rarefied, darker "beats" as I stagger forward.

The way I make myself weave in and out of the living and the dead Dione, is dangerously easy to dismiss as a mad dream; the moment I do that, I shall strangle and die; so I strive to remember what Hriri said: that there's no such thing as illusion. The sequences of instants, in one of which this world is friendly to human life, while in the others it is deadly, are both strung along the same line of reality.

What are the big fat enemy cones seeing right now? Do they glimpse me as a shimmering streak, flickering in and out of view? If it's something like that, I hope the result is I'm a difficult target.

My greatest danger is, that they might copy me, for I'm sure they can, and do, live in more than one sequence along the time-line. But perhaps, for a few precious minutes, I can enjoy the advantage of surprise. I continue to reel forward, frantic with determination to retain my hold upon the adjusted beat, the rhythm of moments along which I have dodged so far.

A greyness looms in front of me, a smooth wall - the city wall!

*

What happened then? I was too exhausted to notice except I felt a rumble and a curtain of hardness drawn aside. I'm through the wall, anyhow. I turn to see that the door or gate has clicked shut behind me. Then as my head lolls with exhaustion a view of the interior of Erzent swims before my eyes. I'm about to collapse - heck, this doesn't look good for a Terran rep who needs to cut a good figure.

I collapse onto something which starts to roll along; it conveys me between weirdly beautiful objects, as numerous and tall as trees in a wood, but of a nature which I cannot even imagine: like knobby metal stalagmites, but with cubes budding in fractal arrangement all over. I'm glad to see that the sky is back to being steadily blue; more than glad that I'm breathing normally; it means I'm back, thank goodness, in the me-friendly time-beat, which is to say, regular synchronicity with the humanly habitable sequence of moments on this world. From now on, I pray, let there be no more variations along that line; the experience has gutted me.

I am taken across a smooth floor to halt before a Dionean, with about twenty others of his species ranged in an arc behind him. I raise myself on one elbow, glancing down and forward. Comparing them with what I'm on, I belatedly understand that I've just been riding atop one of them.

Dioneans are wheeled platforms. In form they are truncated cones with the top three-fourths sheared off. That provides them with a platform two yards wide and a yard off the ground, which is why I was able to flop onto one of them so conveniently. Even when they're just standing, they continuously revolve, in a slow twirl which displays their sides, showing them to be studded all around with what look like eyes, grille-like ears and/or mouths.

I must hope that the sight of all these whirling wheelers won't make me queasy. It's one thing to sit in a TIA library back on Earth and read skimpy reports from travellers who've met the creatures on their occasional voyages off-world to Rhea and Titan; another matter altogether to be here in the flesh.

From beneath me I hear a click-scrape-click-scrape. The foremost Dionean, who is distinguished by a lemon-coloured stripe around his middle, says in a flat voice like a tinny station announcement:

"We - must - all - speak - Terran - in - honour - of - our - guest."

The voice underneath me says, "Apologies - Curber - Lestu."

The lemon-striped leader then says to me: "Terran - man - you - are - welcome."

I realize I don't at all dislike the machine-like tone; on the whole, I prefer aliens to sound like aliens, rather than, for example, the unsettlingly fluent Hriri. If only I weren't so tired I would get up and bow to my host, but as things are I remain draped over the top of his hench-being, while reckoning that a wheeled species is not likely to possess other furniture suitable for a wearied human guest.

"Thank you for letting me in so promptly," I reply. To introduce myself, I choose my words with care: "I am Henrik Clerf of the Terran Intelligence Agency, here to gather material for a report on how best we should respond to a distress call we received on behalf of your world. The call came from you, did it not?"

"Yes - from - me - I - am - Barenga - Lestu - Curber - of - Erzent - only - only - " the repetition clearly signifies disappointment - "report - not - help - "

I firmly say, "My report will enable my superiors to decide what help, if any, Earth can or should give you."

"If - any - if - any - that - means - you - don't - trust - us - "

You've got it, chum, I don't say. Out loud I hopefully pronounce, "Trust grows with time and knowledge."

"Very - well - I - shall - ensure - you - have - the - time - "

"And the knowledge?" say I.

"You - have - it - already - we - have - been - invaded - by - the - hideous - Kahakgu [Tethyan] - cones - "

I reckon it's best to be frank. I put it to him flatly, "Something's wrong, Curber Lestu. I have seen no invaders anywhere except the apparently inert ring of cones around this city." I shut my mouth abruptly, at the sight of the big gun, which I now see from within its slow, steady circuit of Erzent's periphery. My glimpse of it lasts a couple of seconds, as it passes between two of the artificial "stalagmites".

Quite forcefully the possibility occurs to me that I may never get out of here.

*

It appears that I have had one stroke of luck at any rate. The wheeled being on top of whom I am sitting - "Yielder Nuol" - is quite happy to trundle me about, hither and thither among Erzent's structures, wherever I may wish to go upon Erzent's public floor; and this, I suppose, is something. I can gawp like a tourist at Dioneans who pat and embellish the fractal "stalagmites", or at those who sculpt the row of tooth-like kerb-stones which form the inner lining of the circling Gun's peripheral rail. Everything must have a meaning. Doubtless it's often a fascinating, terrific meaning. But what's the use - I'll never have the time or the chance to know.

No, the bit-by-bit accumulation of knowledge, the inductive attempt to get a general picture, is futile; instead, my only hope lies in being deductive: dig for one fact which gives me a line on all the rest. And the key, I bet, is that Gun.

If its story and function were known to me, I might get to the bottom of what's going on here.

Well then, why don't I just ask?

Ha. The idea gets squashed by caution. Especially as the boss wheelie, Curber Lestu, keeps following me around with a squad of henchbeings who roll in parallel with Nuol at five or ten yards' distance. It is becoming more and more obvious that they are trusting me less and less. If, then, I were to ask for the kind of information that a spy would seek, I might trigger a judgement and a final condemnation.

I compromise with necessity. Instead of asking how the Gun works, or what it does, I ask Nuol:

"How old is that Gun?"

"The - Flumbaan - is - old - beyond - memory," says my steed.

My question, and the answer, are picked up by the Curber. It says, "Halt!"

Nuol halts, and I turn to face Lestu.

Erzent's ruler blares a demand: "Are - you - ready - now - Terran - to - contact - your - superiors - to - request - their - help - in - our - war?"

I sense that a calm answer will not do here. Restraint would not be appreciated as courtesy; rather, my only chance is to allow myself to show irritation, if only to focus my own desperate will. "No!" say I. "Not until you show me that there is a war! You people aren't doing anything, and the cones, the Tethyans, they're likewise not doing anything, and as for your circling Gun, the Flumbaan - the same applies!"

"You - are - not - here - to - doubt - us," says Curber Lestu with a voice which his meaning renders even more coldly flat than usual. "If - you - are - not - for - us - you - are - against - us. Probably - a - spy."

Again the intuition comes that I myself had better not be cool, had better hotly rebuke the lemon-girdled wheelie.

"You are threatening me, and thus tempting me to lie, lie to save my life, by agreeing to committing Earth to sending military help, whereas in fact I do not possess that kind of authority. The result, of pretending to have it in order to save my own skin, will not bear thinking about: Earth would be shamed throughout Ekalap." I alter my tone, "Now then, Nuol, please resume the tour of the city. Take me to the edge."

My hot words seem to have had an effect; the Curber and his squad withdraw some further distance, watching me borne off by Nuol.

I have probably bought myself a bit of time, though I suspect it's only minutes.

Here's the rail running round the edge of Erzunt, and I arrive just in time to meet that darned Gun, the Flumbaan, as it slides past on its perpetual circuit, the barrel pointing out at the motionless besieging blobs on the horizon, who must number some hundreds, all facing towards the city. Though the eyes of the cones are too far off for me to discern them, I sense their stare.

I am overwhelmed by the absurdity of this mission. We of Earth are clueless about the Dioneans. How can I possibly fulfil my mission? By relying on luck? I'd willingly buy some of that. By hunches and inspired guesswork? The jokes one hears back at Base, on how agents are commonly expected to do the impossible, are, I now realize, only half-jokes after all. And the inspired guesswork has to pop into existence out of nothing.

"Well, is there aught else for me to visit?" say I. "Come on, Nuol, give me some ideas. I need them."

"I - can - show - you - one."

"What is it?"

Nuol swivels me so as to face down an avenue. At its end I spot an impressive greyish pyramid, maybe four hundred feet high, with sides that slope at fifty degrees or so. Nuol says, "The - Gulf - of - Ages."

I gaze at it, and repeat, "Gulf of Ages... I guess it's as good a name for a historical museum as any."

Nuol makes no comment.

I continue, "Well, let's have a closer look; though I suppose I shan't be allowed inside."

It was with trepidation that I made that last remark. Risky, thus to "try it on": even casually to request entry to any of the buildings of Erzent might well be to stretch the scant patience of my hosts to breaking point. So just what, I ask myself, was I playing at?

Sure, if it is a history museum it might, just might, have information about the Gun, that piece of artillery "old beyond memory". But then, supposing I do gain some vital insight, could I make some use of it in the time available? A long shot indeed, even if this were a human culture! Whereas here, if I found myself in front of an exhibit designed to reveal the secrets of this place, I'd be unable to read the captions... and a curator, if any, would most likely shoot me.

Anyhow, the wheelies surely won't let me in.

Beginning to roll towards it, Nuol contradicted me: "You - are - allowed - in."

*

Approaching to within stone's throw of the pyramid, I begin to notice that its lower sides are pleated and that the pleats curve to conceal what look like open entrances.

My conveyance halts a few yards from where it looks like I may go in. I descend, say "Thank you, Nuol," and wonder if I dare ask him to wait. He's not a taxi, and I do not dare. Can't even bring myself to say, "I won't be long".

I walk round the edge of the 'pleat'. A tall aperture in the pyramid's wall is temptingly revealed. I enter, to find myself in a majestic ground-floor chamber, its ceiling high enough to allow a looming, distracting medley of giant exhibits. One of them, in the centre, draws my gaze more than all the others because it is in motion.

In accordance with my training, mental blinkers discipline my mind to concentrate on one thing at a time, so that I am able to ignore the suggestions of overgrown praying-mantis shapes around me, and focus on that revolving central exhibit. Praise be to Providence - the thing is a model of The Gun!

Half life-size; and merely turning on an axis, rather than travelling on a round track. Still, undoubtely a model of the Flumbaan.

And it is ringed by a sloping lectern, doubtless packed with data...

Then comes a discouraging backwash of my previous thoughts. They repeat how futile it must be, to hope to glean vital information from alien records in time to be of use.

Wait, though! If the records really are aeonian...

A comparison leaps to mind: the warning notices on Terran repositories of nuclear waste.

Those toxic dumps were constructed back in our early third millennium, to store materials with a radioactive half-life measured in hundreds of thousands of years.

The problem they faced was how to put up warnings which could be understood, say, a quarter of a million years hence, when surely no present culture or language would still be in existence.

The designers knew they must rely on symbols and pictures.

I walk forward towards the central exhibit, in the hope that I shall find a similarly wordless explanation of the mystery of the Flumbaan.

I reach it and start to walk round the panel-lectern that rings it. I gaze at many diagrams and images of the gun and the city of Erzent. And as I do so, I see, at the corners of pictures, little designs which look like finger-icons, or tentacle-tip-icons. It's an invitation... I dare to touch them, whereupon I almost cry aloud with satisfaction. At my touch, the stills become movies! Now to see what there is to see!

...An hour or so has gone by, an hour of watching construction movies, with fascinating views of the city and its population. The people look much smaller than the Sreepans of today, with fewer midriff-organs. The movies are accompanied by a slew of engineering diagrams which mean nothing to me.

No, that's not quite right: here's one which, though technical, starts to make possible sense; have I hit the jackpot? It's maybe a trial-run of the Gun, to show what its purpose is.

I touch the icon to watch it again. A cartoon animation, it shows odd trellis-like invaders descending from the sky. They surround the city; they loom, threateningly. In response, diagrammatic waves press outward from the Gun and hit them. The effect is drastic and peculiar: the aliens wilt, they deconvolve, they lose their size and complexity...

Meanwhile, as I gape at all this, I hear a rumble of wheels from beyond some stacks. I freeze as the rumble grows louder. Snouts of ray-guns appear, followed by the Curber and his squad of henchbeings rolling into view.

"You must have understood," the Curber's flat voice grates. "You have been shown how our Flumbaan works. So the moment has come for you to contact your Terran superiors and confirm that they may send us their armies and fleets."

Let anger do its work. "How can you expect them to understand? I myself only understand in pictures, not in words!"

But the Curber's reply is, I have to admit, too clever for me:

"Just tell them this: the Flumbaan is an anti-entelechy gun."

Oh boy, he knows my language better than I do. I'd never have thought using of that term. Entelechy - the realization of potential. And anti-entelechy? Stopping, or even reversing, development.

I repeat, "They won't understand."

"You will remain here as our hostage until they do."

How can I get out of this? I can't commit Earth. Nor dare I lie, which would compromise Earth's reputation.

Anger - my only recourse -

I fume, "But anyway your so-called anti-potential gun isn't doing anything!"

"That's enough," grates the Curber. "You deny our achievement."

"I deny it, yes. I have to! It's useless - a nullity!"

"Die, then." A limb that sprouts from the Curber's midriff is lifting his ray-gun at me.

"Hey, hang on, I'm your hostage, remember! What use to you is a dead hostage?"

The weapon continues to lift and I suddenly realize that I have no monopoly of anger; Curber Lestu possesses at least as much of the simmering emotional brew as I. My appeal to reason, to consistency, thus has no effect, since I've mortally insulted and infuriated him, causing him to upgrade his threat to a harsher, final response.

*

Fired! Blam, a change, a total change: I can't see a thing: all has gone milky. Can't have been that weapon.

Somebody else must have interfered. Who else but Hriri? Ah, distantly I hear his unmistakable voice. He's sorting something out, but his Oxford tones fade from my ear, and I guess my own thoughts must suffice while I exist in this creamy fog.

Dream-drivel bears me along. I think of how it was inevitable that I survived: it had to be so: a sort of anthropic principle applied to story: I am the story-teller so I must live to tell...

The "cream" clears and I see Hriri, hopping to and fro amid the motionless Dioneans. "Come on, Henrik old boy. Time to leave," he says. "I'm finished here."

I sniff. A curious staleness suffuses the air. Perhaps it's because it's absolutely still, not just to the normal extent that air can be still. I can imagine that its very molecules are suspended without motion except where I barge my way. Anyway, it's obvious what Hriri has managed to do. Stop Time. Except for us. How has he managed to confine the effect so as to include just himself and myself? I think about it for a moment as I follow him out, and then I almost laugh. What a trivial question it is compared to the main one, of how can it be done at all.

Outside the building, he heads for the city rim, and I already see he's brought our saucer-vessel down close.

"Hriri," say I, catching up with him, "is there anything you can't do?"

"Don't be too impressed," he said. "The gadget I used doesn't always work. Physical laws fluctuate in Ekalap. So you always have to accept an element of risk. But even if you had been killed by Curber Lestu, the trip would not, for me, have been a waste of time."

"That's good to know," I acidly reply.

"No need to sound bitter. You've passed the character-test with flying colours."

"And that's all it was? Not a real investigation on my part?"

"I," said Hriri, "was the one doing the investigating."

At the entrance to our ship, he, and I, pause for a last look at the cone-shaped besiegers of Erzent. They still look formidable, but I suppose Hriri can play as he likes with them. Saturnian science - is there any limit to it? And Mimanteans like Hriri are likely to glean more scraps from the Masters than are likely to be scavenged by the peoples of the further moons. I say out loud:

"I suppose you can defeat the Tethyan invasion single-handed any time you like, with a gadget like the one with which you rescued me."

"There never was a Tethyan invasion," he shrugs, taking my breath away; as I strive against this latest bewilderment he performs some "click" which immediately freshens the air, and I know without being told that local Time is moving again. "Time to go," he says, "before our friends in Erzent glance this way."

We walk up a ramp into the saucer and within a minute we have hummed up into the sky.

Settled in orbit, he explains:

"What you Terrans call the "Rings of Saturn" are only the visible Rings, the innermost such zones which the Great World, Yimdi, possesses. Other zones, other Rings, extend further out, coterminous with Yimdi's satellite orbits.

"My task is to investigate how each of these invisible Rings plays its part in the evolution of the peoples of Ekalap. I already know that one of them covers my own world, Mimas, together with its neighbour Enceladus. The next pairing is that of Tethys and Dione.

"Just as the Enceladans are destined to follow Mimanteans in physical development, so the Dioneans must eventually follow the Tethyans. Indeed this process is far advanced. Almost every Dionean has become a full cone, and only the die-hard frustra, the people of Erzent - the city of lost causes - still resist their progress to a higher shape..."

"Then it wasn't a siege at all!" I cry.

"Depends what you mean. What you saw encircling the city was the advanced population of Dione, trying to send soothing thoughts wrapped in red sparks of sympathy and reassurance into the terrified redoubt of those who cling to their old shape. They are patient; time is on their side. Of course, if the Flumbaan still worked, the folk of Erzent might put back the clock of history, but it has not worked for a long time. Only, they refuse to admit it. And that's where things got nasty for you. But so long as my, er, gadget worked, you weren't in real danger."

"Oh yes I was," I corrected him grimly. "The danger of making a fool of myself."

THE END

notes made when composing the story

introduction

This tale is intended as an experiment in "open writing" - that's to say, composition in full view. Vastly different from my usual aim which is not to display anything at all before the finished product.

It'll probably be a while before I even get down to any actual story-text. First I've got to struggle with devising at least the sketch of a plot.

All I have at the moment is a vision. An elusive idea, of a little grey-and-while world, where the dominant life-form are cone-shaped beings who slide around the smooth Dionean plains.

Whoops, I just noticed that in my The Arc of Iapetus I refer to the Tethyans as "conical" whereas the Dioneans are "hexapods". Oh dear me. Can these vital data be reconciled in some way? Probably not. Unless the conical stage is part of a temporary self-image... Give me time, I'll work something out. [See the section below, "Using inconsistency".]

What's the "rescue" of the title referring to?

Not sure yet. Maybe a Terran, studying the cones, gets sucked in to their viewpoint - tempted in some way analogous to R Sheckley's "metaphoric deformation" idea (see Sheckley's Mindswap).

But I'm reluctant to place principal reliance on somebody else's idea.

More thinking needed.

using inconsistency

Re the cone problem - the fact that my current vision makes the Dioneans cone-shaped whereas in a published story it is the Tethysians who are that shape and the Dioneans are "hexapods":

Let's use a theory of evolution-by-radiation. Not the respectable idea of radiation-sparked mutations getting promoted by natural selection. Rather, a quite different process like that suggested briefly by Eric Frank Russell in his novel Dreadful Sanctuary. It calls it a "solar-potency" theory, to account for humans appearing independently on the four inner planets. A wonderful, COMOLD-free idea which allows for telemorphs like those of Burroughs' Barsoom, Amtor and Va-nah. Now, instead of the Sun's rays causing this convergent evolution, I could use weaker, longer-wave radiation from Saturn. The rays have caused similar evolution on the neighbouring moons Tethys and Dione. Tethys has progressed to the cone-stage; Dione is on the verge of doing so but its people are still predominantly hexapod. The Dioneans are anticipating their cone-hood by force of will, and this creates effects which entrap an unwitting Terran investigator... hey, this stuff is almost writing itself.

Inconsistencies are a wonderful seed-

old notes - doubtless mostly unusable

"I get suspicious," I said, "when people agree with me so easily. It's like I'm being humoured."

My factotum, CT4500 or Clever Trevor, shrugged. "If..."

Holding the simula of Dione as I seek life there.

"You're welcome to it, if there is."

A god with a small "g" can be defined as a creature whose powers are so great as to seem supernatural, though without any real qualitative transcendence.

It must be fantastically dangerous, being a god. Dangerous for the mind. Easy to go loony and not know it. Especially since by now - AD 99,998 - there are so many of us. Or rather, it would be dangerous, except that, to cope with this peril, we have evolved a corrective.

That old Terran Common Era calendar, so surprisingly durable and popular, is itself one clue to the corrective. The corrective which can be summed up in six syllables -

Retro Stability!

Issues come up: themes:

Spooky question: why are there no interstellar visitors? Possible answer: Star-god evolution maybe not a survival trait? Systems get full, collapse under their own psychic weight...?

Pocket-truths.

Re-sets.

Lifeless Dione - did I do this?

Just a probability world - but I may have bullied others out of existence, in my selfish urge to wipe a slate clean.

Visit to Earth archives to easy my mind.

Troposphere 250 miles deep. Blue. Like Neptune. Surface invisible.

Retro tech. AD 2000 or even 1950. Filing cabinet, giant, 100 miles high. Physical by-laws surrounding it, sparkling around it.

Vendetta - grav. control slips, newly, on side of cabinet.

assets

Saturn's medium-sized moons have evocative, beautiful names, and seem to shimmer with potential personality. They've hardly been used at all in sf. What a lush field for a writer to frisk about in! The task then is to bring out their personalities.

possibilities

Use an analogy between "ontology recapitulates phylogeny" and the idea that there are sequential gradations of reality: a pecking order, as it were, of probability-worlds. That way I might fit in the creaky AD 99,998 vision (see "old notes" section).

names

I need to establish the native Dionean name for Dione. Over my breakfast cereal I was reading a history book, as is my wont at breakfast; at the moment it's a re-reading of C V Wedgewood's The Trial of Charles I. When thinking about names for the Dione story I ran my eye down a page of text and began to read some words backwards, and mentally to shuffle the letters around a bit more.

The word "place" came to my attention. Backwards, it's "ecalp". Add a vowel and change the c to a k: Ekalap. Promising!

(By the way, ERB in his Amtor series uses the suffix -lap for some place names, if I remember correctly. Could the great man possibly have gone through the same thought-process...?)

But I'm not completely happy about referring to Dione as Ekalap. Another name that popped (from I don't know where) into my mind today, "Srepp", won't leave me alone till I use it for this Saturnian moon. "Srepp" is... kind of odd, rather harsh, but somehow it's the one for my purposes.

So - Dione is Srepp. And what about Ekalap?

Tethys? No, because I find myself wanting to keep "Ekalap" as a general term for the community of Saturnian moons. The instinct to do this is quite insistent, believe it or not.

Then what about Tethys? I believe I'm going to use the third name that occurred to me at breakfast - a crude, short name, used by the envious, somewhat resentful Dioneans for their neighbour moon...

Tethys is Kahak.

mustn't get too tricky - but here's an idea

Possible start to the tale, or ingredient thereof:

The protagonist, a novice Terran Intelligence Agent, has been sent to Dione to investigate rumours of hostile infiltration by Tethyans. The rumours have been sparked off by sightings of cone-shaped beings on Dione in unusually large numbers. [It is not yet realized that these are actually Dioneans evolved or pretending to be evolved to look cone-shaped.]

Now here's the tricky bit.

The protagonist reflects on a warning he remembers being given, to the effect that he must beware of the strange Dionean sense of humour. In a flashback he re-lives this memory: "You will be in danger of being led to believe ludicrous things - so to avoid this, you must maintain your critical faculty. On no account give credence to inherently absurd beliefs about the background to your mission. Maintain your sense of realism and you will be safe from deception..."

I can then, of course, pile on the dramatic irony by making it obvious to the reader that this has already happened - even as the Agent checks over his own memories to make sure, as he thinks, that he has preserved his sense of realism.

For instance, he could go over a [false?] memory of being hired by a council of the Ekalap and registered as a spy quite openly and officially, in accordance with a supposed custom of the Saturn System whereby spies are accepted like medieval heralds were on Earth, as members of a special order, with rights of immunity during conflict.

Only - better watch carefully how I go with all this. From my authorial point of view, playing around with ideas of illusion has the possible disadvantage, that it may incur the danger of thinning the immediacy of the adventure, reducing it to the level of arbitrary dream where anything goes.

preserving the bite

In the above section I touched on the problem of anything-goes wishy-washiness, brought on by over-reliance on phantasmagoric illusion.

I don't mean to downgrade successful dream-literature, of which George Macdonald's Phantastes is a masterly example. But sf is a different kettle of fish, or ought to be.

I can think of two sf greats who partly fell into the trap of over-reliance, not exactly on on an anything-goes theme, but on a sort of stock workhorse-explanation: Leigh Brackett with her penchant for radioactive powers (see for example The Big Jump and The Moon that Vanished), and C L Moore with her penchant for vampiric mind-powers (see most of the Northwest Smith stories).

Comparably - si parva licet componere magnis - the thematic over-reliance which may undermine me if I let it, concerns the idea that there are degrees of reality, that a person may swerve or veer along a spectrum of what is real, and that, in effect, there is actually no such thing as illusion. There, I said it. That's going to be what underpins this story - heaven help me. An artistic risk if ever there was one. An idea so intrinsically open-ended, that wishy-washiness threatens to inundate the plot in a tide of iridescent mush. How to preserve the bite, to keep the reader interested in what purports to be a real story with real hard happenings?

The risk may be increased if I make the wrong decision about whether to tell the story in the first or in the third person.

My notes so far were written on the assumption that I'd narrate in the third person. But now I'm wondering - tempted by the first-person idea with its greater ease of immediacy and conveying the thoughts of the protagonist.

A further question: if it does get told in the first person, should it also be told in the present tense? That would be even more immediate.

Too much so, perhaps? Increasing the hallucinatory vividness too far?

On the other hand I have the example of one of my favourite stories to follow: A E van Vogt's Fulfilment. That is told in the first person and in the present tense, and it's so good that I've re-read it innumerable times. No clearer proof can be required, that this mode of story-telling can succeed in the hands of a master... Um.

Yet another thought: I seem to remember Keith Laumer writing some good stories which are mostly first-person yet with a third-person "frame", i.e. an introduction and epilogue in the third person. For example, Assignment in Nowhere.

That might be the option I need here.

And Laumer is an inspiring and comforting example on the phantasmagoric-peril front too. His Knight of Delusions - come to think of it - runs all the risks I've outlined in this section, and triumphantly avoids them. (See Time Travel and Reality Change.)

personnel and geography

Found a name for the main protagonist: Henrik Clerf - a novice Terran Intelligence Agency field-operative. He's a young man with an obsessive interest in old movies and the gadgetry of film projection; his superiors think this is a harmless hobby.

The more experienced TIA agent Seth Hurst (later the hero of The Arc of Iapetus; see Vintage Worlds 3) shrugs at the idea of sending Clerf to solve the mystery of Dione; his attitude is, might as well let him have a go; when he fails, as is most likely, there'll be time enough to send someone of higher calibre.

Hurst however is then amazed to learn of an applicant from Mimas named Hriri who has asked to accompany Clerf to Dione. The Mimanteans, though somewhat absurd in appearance (squat, hairy, troll-like shufflers), have a reputation for power and wisdom second only to that of the Saturnians themselves.

Hriri's function in the story is to focus the reader's interest on the ambiguities of Dionean life: especially to head off the idea that the only types of theory which could allow one to turn bleakly bare Dione into a lushly fertile Dione (a transformation which has occasionally been reported) are either hypnotism of some kind or the old trope of a standard probability-world or dimensional-shift story. Hriri, it turns out, shows us there's an altogether different option. He uses Clerf's interest in old movie-projectors to help him understand a strobe effect, by which every nth instant of quantized time is allocated to a lush coexisting facet of Dione's nature, allowing the explorer to focus on those instants alone, and thus, by ignoring the other instants which would contradict it, to experience the lush facet on full power.

"Switching on" in this way to the lush Dione, the visitor finds that the revolving city of Erzent becomes visible. The city has to revolve, turning through 360 degrees every half hour or so, to keep its one major gun trained on the dangerous growths which keep sprouting around it. The city's survival and prosperity is thus an ancient equilibrium which relies upon power and vigilance.

the plot's opening, middle-game and end-game

In plotting the story I had reached the stage - pursuing an analogy with chess - at which the opening and the end-game were adequately sketched out, but the middle-game remained a blank.

Opening: Agent goes to Dione to investigate apparent invasion by Tethyan conoids.

End: Agent discovers there is no invasion: the conoids are native Dioneans who have reached the next stage of their evolution, which involves convergence with Tethyan forms.

But what happens in the middle? What delays the denouement enough so as to allow for a middle?

Here's an example of the problem itself furnishing its own solution. After some hours of apparent mental inertia during which it all stewed in my head, I suddenly found that the mere juxtaposition of opening and end caused the middle to pop into existence to fill the gap, as follows:

Agent takes a while to get the answer. Why? Because he's delayed. What or who delays him? Atavistic Dioneans! Dioneans who don't like the trend of their own evolution. Stick-in-the-mud Dioneans who want to retain their species' old shape and who want Terran help against those who are becoming conical.

These reactionaries spin a tale to the Agent, imploring him to side against the "invaders".

Questions remain; details need to be worked out. But that's the shape of the "Middle-Game".

And with that, I now have the major elements of the plot.